THE

PIERO DELLA FRANCESCA AT WORK

THE

PIERO DELLA FRANCESCA AT WORK

Austere Beauty

A

mathematician as well as an artist, Piero brought to his paintings an austere

beauty of form that recalls Greek sculpture. But he was also a great colourist

and unrivalled in his handling of light.

Piero's

style is highly individual, and its distinctive qualities are very different

from those so often admired in the work of 15th-century Italian painters. In

place of decorative detail and graceful fancy, he offers geometric harmony and

a classical severity that recalls Greek sculpture. It is these features,

together with his power to capture the fall of light, and his richly harmonious

colouring, that make his work so appealing to modern eyes.

And

although he was well immersed in the sophisticated humanist culture of

Florence, Urbino and Arezzo, many of his pictures retain an almost primitive

power. The Virgin of the Madonna del Par to, the figures of the aged Adam and

Eve depicted in The Death of Adam, and the angelic musicians of The Nativity

seem to reflect an ideal of humanity that is at once simple and sublime.

Since

Piero's own writings are concerned exclusively with the technical and

mathematical aspects of paintings, we must turn to the pictures themselves for

evidence of his artistic ideals. In many respects his work is fairly

conventional. Almost all of it is on religious themes, often depicted within

the traditional framework of the altarpiece. He painted both in fresco and on

wooden panels, and seems to have come only gradually to the use of oils, which

he often employed mixed with the more familiar tempera medium.

A MASTER OF PERSPECTIVE

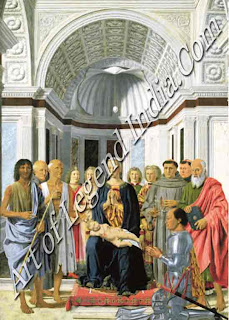

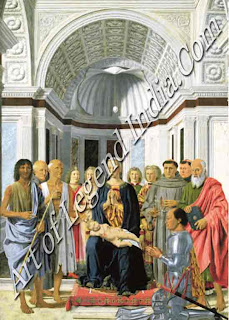

His

outstanding claim to purely technical originality lies in his mastery of

perspective. We can admire this in the architectural detail of such paintings

as The Flagellation and the Brera Altarpiece of Madonna and Child with Saints

and Angels. The receding floor and ceiling of the loggia in the former, and the

marble apse which frames the Madonna in the latter, are painted with formidable

precision, heightened by the exact rendering of light and shadow. We know from

Piero's theoretical treatises that this was the fruit of rigorous mathematical

research.

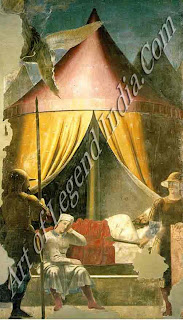

However,

Piero rarely pursued virtuosity for its own sake. In The Resurrection he

employs a double perspective, the soldiers before the tomb being seen from

below in foreshortening, while the upper part of the picture implies a

viewpoint level with Christ's head. But this is more than a display of

technical skill. It is a part of the painting's emotional and symbolic meaning,

which contrasts the slumbering human world with the miraculous awakening of the

risen Christ.

The

face and figure of this Christ are a fine example of Piero's rendering of the

human body. Although his men and women may sometimes seem inexpressive at first

glancy and their bearing almost always seems to be contemplative rather than

active, their vitality and nobility are never in doubt. Moreover, besides a

magisterial ability to create ideal, heroic figures, Piero showed in his work

as a portraitist that he could capture the unique character of an individual

sitter. His portraits of the Duke and Duchess of Urbino are among the most

unforgettable images of the Renaissance. It is likely that his work in fact

contains several portraits which we do not recognize as such. For instance,

Vasari tells us that the Bacci family along with other citizens of Arezzo, are

shown around the defeated King in The Battle of Heraclius and Chosroes. The

riddle of The Flagellation, too, depends for its solution on the identity of

the three men in the foreground on the right-hand side of the painting, though

we are unlikely ever to know for sure who they were or what they were talking

about.

In his

work as a whole, however, Piero's gifts as a portraitist are less central than

his power to suggest something more archetypal and timeless in the human form.

The fair-haired young man of The Flagellation and the angels of The Baptism of

Christ and The Nativity all share a serenity reminiscent of Greek sculpture. We

know that Piero, like other Renaissance artists, used models hung with soft

cloth to study how drapery fell and how the light caught it. And we might point

to some particular feature the feet, for instance, whose firm grip on the

ground is so convincing in all these cases as the secret of Piero's craft. But

such details of technique or style cannot in themselves explain the underlying

vision that the painter has so memorably realized.

COLOURS AND SPACE

Another

aspect of that vision, and the one which perhaps gives us the most immediate

and intense pleasure, is the harmony of Piero's colours. Despite the damage

they have suffered, the Arezzo frescoes never fail to strike visitors with

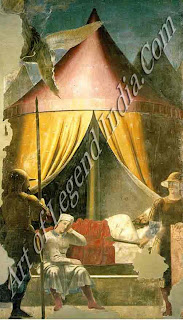

their luminous freshness. This quality is seen at its best in Constantine's

Victory over Maxentius where Piero's restricted palette achieves a richly

symphonic effect. The same harmony unites the colours of the garments in

Flagellation, and brings together the two angels in the Madonna del Parto,

whose attitudes and clothing echo one another in a heraldic mirror-image.

Another

aspect of that vision, and the one which perhaps gives us the most immediate

and intense pleasure, is the harmony of Piero's colours. Despite the damage

they have suffered, the Arezzo frescoes never fail to strike visitors with

their luminous freshness. This quality is seen at its best in Constantine's

Victory over Maxentius where Piero's restricted palette achieves a richly

symphonic effect. The same harmony unites the colours of the garments in

Flagellation, and brings together the two angels in the Madonna del Parto,

whose attitudes and clothing echo one another in a heraldic mirror-image.

Still

more characteristic of Piero is the sense of airy space created by the light

that fills his skies and falls upon his landscapes. Here, he largely dispenses

with perspective, using pure colour in a way that anticipates the

Impressionists. In The Nativity, his angelic and human figures are boldly

grouped against a countryside receding far into the distance. The same effect

is even more daringly successful in the Uffizi diptych, where no middle ground intervenes

between the profiles of Federigo and Battista and the idealized landscape of

their dominions. This land appears far below and behind them and is bathed in

the clear, bright light of the Italian sky.

THE MAKING OF A MASTERPIECE

THE MAKING OF A MASTERPIECE

The Flagellation

The

formal unity of this enigmatic masterpiece is achieved by consummate skill in

perspective, reinforced by the harmonious grouping of the figures. But its two

scenes are entirely separate. Piero has emphasized this by illuminating Christ

from a light-source behind the right-hand flagellator's arm, while the

foreground is lit from the left. The painting challenges the viewer to find

some significant connection between the scenes. Christ's suffering must have

some allegorical or symbolic meaning, but how is this related to the

conversation in the foreground? Many scholars now reject the local tradition

identifying the foreground group as Urbino courtiers. Instead, they see the

picture as a commentary on the tribulations of the Eastern Christians at

Turkish hands, an interpretation borne out by the Oriental turban worn by the

man with his back to us. The three men conversing might then be ecclesiastical

and political dignitaries, the bearded man perhaps representing the Greek

Church. But in the absence of any documentary evidence, we can only speculate

on the picture's meaning, while continuing to marvel at the intricate detail

and overall harmony of its composition.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

THE

PIERO DELLA FRANCESCA AT WORK

THE

PIERO DELLA FRANCESCA AT WORK Another

aspect of that vision, and the one which perhaps gives us the most immediate

and intense pleasure, is the harmony of Piero's colours. Despite the damage

they have suffered, the Arezzo frescoes never fail to strike visitors with

their luminous freshness. This quality is seen at its best in Constantine's

Victory over Maxentius where Piero's restricted palette achieves a richly

symphonic effect. The same harmony unites the colours of the garments in

Flagellation, and brings together the two angels in the Madonna del Parto,

whose attitudes and clothing echo one another in a heraldic mirror-image.

Another

aspect of that vision, and the one which perhaps gives us the most immediate

and intense pleasure, is the harmony of Piero's colours. Despite the damage

they have suffered, the Arezzo frescoes never fail to strike visitors with

their luminous freshness. This quality is seen at its best in Constantine's

Victory over Maxentius where Piero's restricted palette achieves a richly

symphonic effect. The same harmony unites the colours of the garments in

Flagellation, and brings together the two angels in the Madonna del Parto,

whose attitudes and clothing echo one another in a heraldic mirror-image.

0 Response to "Italian Great Artist Piero Della Francesca at Work"

Post a Comment