Images of the Soul

Munch's

belief that art should be of people who breathe, who feel emotions, who suffer

and love' resulted in unprecedented images of the innermost feelings and mental

anguish of modern man.

When

Munch died, there was a copy of Dostoevsky's book The Devils by his bedside. It

seems a fitting choice for a man who created his own nightmare visions and who

provided the earliest pictorial definitions of paranoia and angst. Munch

himself did little to dispel this image, claiming that art was his life's

blood, costing him pain and suffering.

Initially,

his personal style was built up from his own subjective view of the world

around him. After his early naturalist phase, Munch's first important paintings

including The Sick Child were described as 'impressionistic' by the critics, at

a time when the word was used as a term of abuse. But rather than studying the

variations of light caused by the weather or the time of day, Munch chose to

concentrate on the momentary visual distortions that can occur as the eye

adjusts to different conditions in effect, tricks of the light. As a result,

most early commentators singled out Munch's apparently cavalier use of colour

for their criticisms.

Initially,

his personal style was built up from his own subjective view of the world

around him. After his early naturalist phase, Munch's first important paintings

including The Sick Child were described as 'impressionistic' by the critics, at

a time when the word was used as a term of abuse. But rather than studying the

variations of light caused by the weather or the time of day, Munch chose to

concentrate on the momentary visual distortions that can occur as the eye

adjusts to different conditions in effect, tricks of the light. As a result,

most early commentators singled out Munch's apparently cavalier use of colour

for their criticisms.

From

this position, it was a short step to progress from painting visual impressions

to depicting the effect that these impressions had on the emotions. The Scream

is the most famous example of this. Munch was inspired by a dramatic sunset

which he had witnessed while walking beside a fjord. However, by suppressing

his own features and by transforming the waters and the sky into threatening

shock waves of vibrant colour, he managed to convey the feelings of terror that

he had experienced on that occasion. Munch defended his approach by stressing

that 'Nature is the means, not the end. If one can attain something by changing

nature, one must do it.

From

this position, it was a short step to progress from painting visual impressions

to depicting the effect that these impressions had on the emotions. The Scream

is the most famous example of this. Munch was inspired by a dramatic sunset

which he had witnessed while walking beside a fjord. However, by suppressing

his own features and by transforming the waters and the sky into threatening

shock waves of vibrant colour, he managed to convey the feelings of terror that

he had experienced on that occasion. Munch defended his approach by stressing

that 'Nature is the means, not the end. If one can attain something by changing

nature, one must do it.

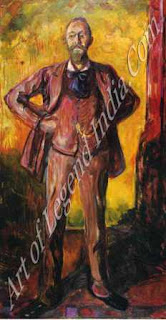

This

directness was reflected in Munch's method of working. When, for example, he

was commissioned to paint a portrait of the industrialist, Herbert Esche, Munch

did nothing for the first fortnight except stay with the family until he felt

he knew his subject. Then he set to work very rapidly, testing his colours on

his client's expensive wallpaper and relying on a simple charcoal sketch on the

canvas as his sole guide for the composition.

During

his Symbolist phase (c.1889-1900), Munch turned to the depiction of ideas

rather than emotions, using the mystical and sexual images that were

fashionable as the basis for his Frieze of Life. In fact, the very notion of a

frieze, with its attempt to simulate the resonant quality of music, was a

thoroughly Symbolist concept.

KEY IMAGES

For the

several components of his Frieze, Munch selected a few key images and reworked

them constantly, varying the colour schemes, the poses of the figures or even

just the titles. 'Art is crystallization' he asserted, convinced that his

revisions would eventually lead to the most powerfully emotive version of any

given theme.

In this

regard, Munch's interest in the graphic arts proved crucial. Originally, he had

taken up etching, in 1894, as a means of earning extra income. However, as the

possibilities of the medium became apparent to him, he grew more inventive and,

at one stage, even acquired the habit of carrying a copper plate around in his

pocket to use like a sketch book.

Munch's

work in Paris, in 1896, with Auguste Clot the printer who had aided Toulouse Lautrec

and Bonnard proved a revelation. He learnt the techniques of making lithographs

and colour woodcuts and, to the latter in particular, he brought exciting

innovations. By sawing the woodblock into smaller sections and colouring these

individually, he was able to produce multicoloured woodcuts easily, without going

through the tedious process of making separate printings for each colour.

Munch's

work in Paris, in 1896, with Auguste Clot the printer who had aided Toulouse Lautrec

and Bonnard proved a revelation. He learnt the techniques of making lithographs

and colour woodcuts and, to the latter in particular, he brought exciting

innovations. By sawing the woodblock into smaller sections and colouring these

individually, he was able to produce multicoloured woodcuts easily, without going

through the tedious process of making separate printings for each colour.

Prints

were invaluable to Munch because the plates or blocks could easily be reworked

or printed in different colours, thereby greatly increasing the scope for

experiment. There was also a degree of feedback, from the prints to his

canvases: compositions were often refined in lithographs or woodcuts and then

translated back into paint, producing a simplified and more powerful image. In

his later years, Munch grew increasingly reluctant to part with his paintings

and, where he was obliged to sell, frequently made replicas for himself.

In his

heart, he still nurtured hopes of displaying his works together, confident that

the full force of his very personal style could only be appreciated if viewed

en masse.

The

availability of his art to a wide public was of prime importance to Munch and,

in a sense, this single desire governed his interest in friezes, graphic work

and large murals. He despised the notion of a bourgeois art, where the

academies became factories for producing paintings which vanished into the

houses of the wealthy forever.

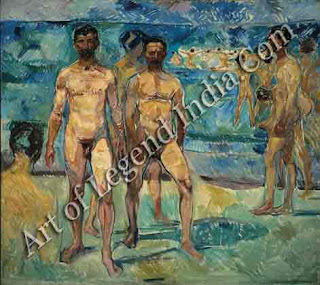

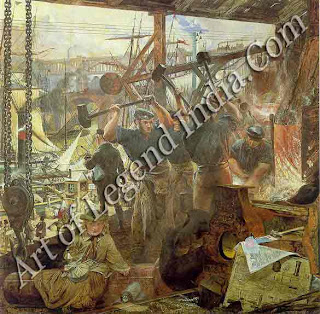

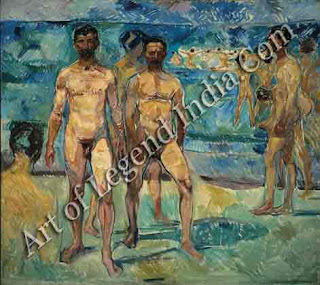

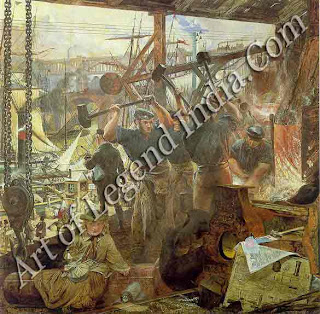

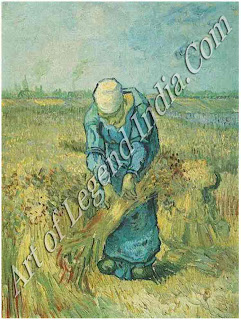

After

Munch's return to Norway in 1908 his paintings lost their emotional intensity,

and he turned to his native landscape, nature and working people for the

subjects of his work. These themes were central to his large-scale public

projects such as the University murals and the frieze at the Freia chocolate

factory. But even in his apparently realistic works, traces of his old

obsessions are still discernible. The bowed head of the model in his Nude by

the Wicker Chair carries faint echoes of the shy apprehension in Puberty, while

the workmen in Workers Returning Home have the same remorseless formality as

the faceless figures in Anxiety.

Munch was,

in every sense, an isolated figure. He had no pupils and he declined

invitations to join avant-garde groups like Die Brucke. Even to his bohemian

friends in Christiania and Berlin, he had remained something of an outsider.

However, his haunting images linking the themes of sickness, death and raw,

sexual power neatly encapsulated the mystical spirit of the Symbolists, while

the directness of his style, with its daringly inventive distortions, paved the

way for Expressionism.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Initially,

his personal style was built up from his own subjective view of the world

around him. After his early naturalist phase, Munch's first important paintings

including The Sick Child were described as 'impressionistic' by the critics, at

a time when the word was used as a term of abuse. But rather than studying the

variations of light caused by the weather or the time of day, Munch chose to

concentrate on the momentary visual distortions that can occur as the eye

adjusts to different conditions in effect, tricks of the light. As a result,

most early commentators singled out Munch's apparently cavalier use of colour

for their criticisms.

Initially,

his personal style was built up from his own subjective view of the world

around him. After his early naturalist phase, Munch's first important paintings

including The Sick Child were described as 'impressionistic' by the critics, at

a time when the word was used as a term of abuse. But rather than studying the

variations of light caused by the weather or the time of day, Munch chose to

concentrate on the momentary visual distortions that can occur as the eye

adjusts to different conditions in effect, tricks of the light. As a result,

most early commentators singled out Munch's apparently cavalier use of colour

for their criticisms.  From

this position, it was a short step to progress from painting visual impressions

to depicting the effect that these impressions had on the emotions. The Scream

is the most famous example of this. Munch was inspired by a dramatic sunset

which he had witnessed while walking beside a fjord. However, by suppressing

his own features and by transforming the waters and the sky into threatening

shock waves of vibrant colour, he managed to convey the feelings of terror that

he had experienced on that occasion. Munch defended his approach by stressing

that 'Nature is the means, not the end. If one can attain something by changing

nature, one must do it.

From

this position, it was a short step to progress from painting visual impressions

to depicting the effect that these impressions had on the emotions. The Scream

is the most famous example of this. Munch was inspired by a dramatic sunset

which he had witnessed while walking beside a fjord. However, by suppressing

his own features and by transforming the waters and the sky into threatening

shock waves of vibrant colour, he managed to convey the feelings of terror that

he had experienced on that occasion. Munch defended his approach by stressing

that 'Nature is the means, not the end. If one can attain something by changing

nature, one must do it.  Munch's

work in Paris, in 1896, with Auguste Clot the printer who had aided Toulouse Lautrec

and Bonnard proved a revelation. He learnt the techniques of making lithographs

and colour woodcuts and, to the latter in particular, he brought exciting

innovations. By sawing the woodblock into smaller sections and colouring these

individually, he was able to produce multicoloured woodcuts easily, without going

through the tedious process of making separate printings for each colour.

Munch's

work in Paris, in 1896, with Auguste Clot the printer who had aided Toulouse Lautrec

and Bonnard proved a revelation. He learnt the techniques of making lithographs

and colour woodcuts and, to the latter in particular, he brought exciting

innovations. By sawing the woodblock into smaller sections and colouring these

individually, he was able to produce multicoloured woodcuts easily, without going

through the tedious process of making separate printings for each colour.

0 Response to "Norwegian Great Artist Edvard Munch - Image of the Soul"

Post a Comment