Joan

Miro

Joan

Miro

1893-1983

Together

with Picasso, Miro is perhaps the most versatile and influential of

20th-century artists. Although he was born into a family of craftsmen, his

father frustrated his early ambitions to become a painter, forcing him to

accept a job as a bookkeeper in Barcelona. As a result, Miro suffered a nervous

breakdown, but it only strengthened his resolve. He left for Paris in 1919,

where he met the avant-garde Surrealists.

Miro

divided his time between France and Spain, and later America, where he executed

murals for hotels and universities. His natural humour and love of anecdotal

detail quickly popularized his work; but it also has a savage and macabre

streak which was released by the shattering events of the Spanish Civil War and

World War 11. Like Picasso, Miro continued his artistic experiments into his

old age.

THE JOAN MIRO 'S LIFE

THE JOAN MIRO 'S LIFE

The Modest Catalan

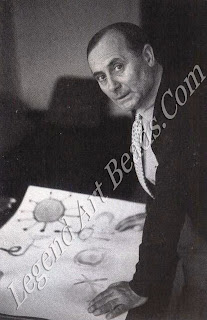

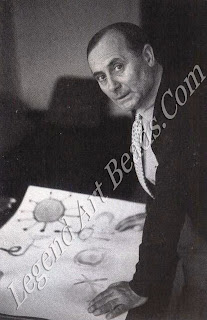

Miro's

taciturn nature belied his profound imagination and creativity. A life of hard

work, divided between Paris and the Catalonian hills, produced unrivalled work

which continues to inspire.

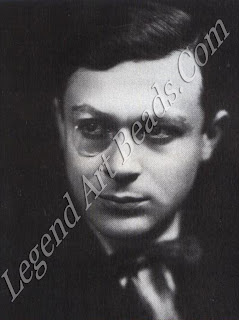

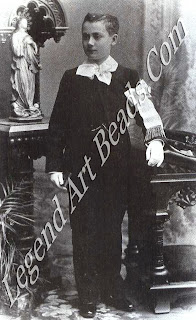

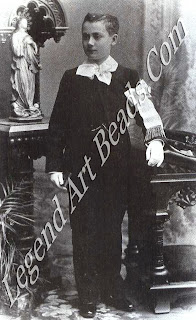

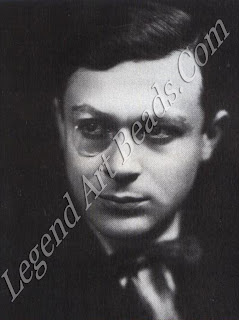

Joan

Miro was born on 20 April 1893 in Barcelona. The family lived in the Pasaje del

Credito in the heart of the old city, where Miro's father Miguel ran a

prosperous business as a jeweller and watchmaker. There was artisan talent on

his mother's side too: Dolores Ferra's father was a skilful cabinet maker. From

the age of seven, Miro was sketching careful portraits and still-life, but

Dolores and Miguel constantly frustrated his artistic ambitions.

Miro

announced his intention to become a painter early on, but Miguel turned a deaf

ear in spite of his son's abysmal performance at school. Miro showed a complete

ineptitude for academic study and was known as 'fathead' by his fellow pupils.

The pattern repeated itself in 1907, when Miro enrolled at La Lonja, the

Barcelona school of Fine Arts where Picasso had studied 12 years earlier. He

was soon dubbed a 'phenomenon of clumsiness'. But his tutor could see a spark

of originality and brilliance in his clumsy attempts, and each week, when

Miguel called hoping to be assured of Miro's incompetence, he was told that one

day, Miro would be a famous artist.

Miguel

was unimpressed and in 1910, forced his son to accept a respectable job as a

bookkeeper for a local drugstore. Miro dutifully obeyed, but it broke his

spirit. The tedium of the work and the stifling of his creative energies

brought on an appalling nervous depression, soon compounded by an attack of

typhoid fever, and in desperation his parents sent him to recuperate at their

farm near Montroig in the Catalonian hills. The surrounding landscape made a

lasting impression on the young artist.

Miguel

was unimpressed and in 1910, forced his son to accept a respectable job as a

bookkeeper for a local drugstore. Miro dutifully obeyed, but it broke his

spirit. The tedium of the work and the stifling of his creative energies

brought on an appalling nervous depression, soon compounded by an attack of

typhoid fever, and in desperation his parents sent him to recuperate at their

farm near Montroig in the Catalonian hills. The surrounding landscape made a

lasting impression on the young artist.

Once

back in Barcelona, Miro was no longer to be dissuaded from his chosen career.

He joined Francisco Gall's liberal-minded art school and associated with the

artists of the Sant Lluch some of whom became lifelong friends, like Joseph Llorens

Artigas. With his new bohemian acquaintances, Miro haunted the Barcelona cafés

and nightclubs, but he shunned their dissipated lifestyle, indulging his

fascination with the Spanish dancers only on paper. He was always the first to

go home. More rewarding were his contacts with the avant-garde French artists

and poets who travelled to Barcelona during the war years, and his discovery of

the Fauve and Cubist paintings at Joseph Dalmau's gallery.

THE LURE OF PARIS

Dalmau

offered Miro his first one-man exhibition in 1918. The public response was very

poor but the artist was undeterred, knowing that success and the international

recognition he already dreamed of could only be found in Paris. The French

capital had a magnetic appeal for him, and in 1919, when Paris was at last

safe, after the war, he made his first trip there. Over the next few years,

winters in Paris and quiet summers at Montroig became his regular working

pattern.

Key Dates

Key Dates

1893 born in Barcelona

1910 accepts job as a

bookkeeper

1911 suffers nervous breakdown;

determines to become a painter

1919 visits Paris and meets

Picasso

1928 trip to Holland

1929 marries Pilar Juncosa

1936 Spanish Civil War breaks

out

1940 escapes France to Palma

1942 returns to Barcelona

1944 ceramic experiments with

Artigas

1947 visits America

1956 builds large studio at

Calamayor

1970 ceramic mural for

Barcelona airport

1983 dies on Christmas Day

Paris

was a stimulating but ruthless city for obscure and impoverished artists. One

of the first things Mire did when he arrived was to look up his fellow

Spaniard, Picasso. Picasso bought a self-portrait from Miro to encourage his

new friend, but sales were hard to come by, and Mini's financial situation was

perilous. His parents provided ludicrously small sums intended to convey their

utter disapproval of his activities. The tiny studio where he worked at 45, rue

Blomet near Montparnasse had broken window panes, and his rickety stove, picked

up for 45 francs in the flea market, refused to work. He was so poor that he

could only afford one proper lunch a week.

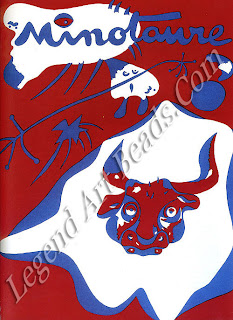

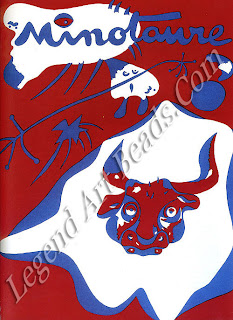

But

there was consolation in the circle of intellectuals, poets and painters whom

Miro met through his next-door neighbour, Andre Masson. Masson, Paul Eluard,

Louis Aragon, Robert Desnos, Anton in Artaud and Andre Breton would frequently

gather to discuss the ideas which Breton set down in the first Surrealist

Manifesto of 1924. Miro was fascinated by their attempts to explore the

subconscious, often through artificially induced means, and attended the

meetings where the poet Desnos and the actor Artaud gave hysterical speeches in

states of hallucination.

These

experiments encouraged Mire to move away from the depiction of everyday reality

in his own work, and to rely instead on his imagination and the hallucinatory

forms and sensations he experienced through extreme hunger. He would sit for

hours staring at the bare walls of his studio and sketching the strange shapes

which appeared in front of his eyes. He did not take drugs himself, and he

remained aloof from the internal squabbles of the group, but he began to

exhibit with the Surrealists, showing his new 'dream paintings' at Pierre

Loeb's gallery and the Galerie Surrealiste.

These

experiments encouraged Mire to move away from the depiction of everyday reality

in his own work, and to rely instead on his imagination and the hallucinatory

forms and sensations he experienced through extreme hunger. He would sit for

hours staring at the bare walls of his studio and sketching the strange shapes

which appeared in front of his eyes. He did not take drugs himself, and he

remained aloof from the internal squabbles of the group, but he began to

exhibit with the Surrealists, showing his new 'dream paintings' at Pierre

Loeb's gallery and the Galerie Surrealiste.

A

contract with the dealer Jacques Viot enabled him to keep afloat financially,

and Viot found him a studio in Montmartre at 22, rue Tourlaque where his new

neighbours included Max Ernst, Rene Magritte and Jean Arp. Miro struck up close

friendships with Arp and Ernst in particular, but he was rarely to be seen with

them at the Café Cyrano in Place Pigalle, or the Café de la Place Blanche where

the Surrealists gathered to discuss theories and write manifestos, or organize

exhibitions.

Miro

was working compulsively, and becoming increasingly secretive about his own

paintings. He kept them all turned face to the wall, away from the curious gaze

of Ernst, who worked in the studio above. One night Ernst and some drunken

friends stormed his studio, sorted through all the canvases to discover their

secrets, and then strung Miro up in a hangman's noose and started to squeeze

the life out of him, pulling hard on the rope. The sober Mini somehow managed

to extricate himself from the noose and went into terrified hiding for three

days.

But

Ernst's drunken revelries never soured his friendship with Miro or their

admiration for each other, and occasionally they worked together, both agreeing

to design the costumes and scenery for Diaghilev's ballet, Romeo and Juliet.

Breton, the dogmatic leader of the Surrealist group, violently disapproved of

their involvement in what he considered to be the bourgeois and frivolous world

of ballet. He staged a demonstration in the theatre on the opening night, and

denounced them in his magazine, La Revolution Surrealiste. But Miro had never

bowed to Breton's intellectual dogmas or his authority, preferring to keep his

distance when it suited him.

But

Ernst's drunken revelries never soured his friendship with Miro or their

admiration for each other, and occasionally they worked together, both agreeing

to design the costumes and scenery for Diaghilev's ballet, Romeo and Juliet.

Breton, the dogmatic leader of the Surrealist group, violently disapproved of

their involvement in what he considered to be the bourgeois and frivolous world

of ballet. He staged a demonstration in the theatre on the opening night, and

denounced them in his magazine, La Revolution Surrealiste. But Miro had never

bowed to Breton's intellectual dogmas or his authority, preferring to keep his

distance when it suited him.

In

1928, Mini visited Holland, where the bourgeois interiors depicted by the

17th-century Dutch painters, and Vermeer in particular, intrigued him. He

brought back postcard reproductions and used them for a series of paintings,

including Dutch Interior, in which he distorted and rearranged the contents of

the originals with a great sense of humour. But soon afterwards, Miro abandoned

the easy charm of these pictures and started on a series of collages and

constructions made from bits and pieces of debris, often salvaged from dustbins;

unpleasant objects and materials put together for their shock value. He

declared that he was going to assassinate painting' which had been 'decadent

since the cave age'.

Miro's

new troubled state of mind had nothing to do with his personal fortunes. In

1929, he married Pilar Juncosa and settled down to a perfectly happy married

life. Two years later, his daughter Dolores was born. But the 1930s held

horrors in store which Miro could not disguise in his art of those years.

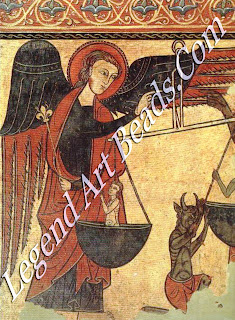

Miro

was now spending more time in Spain, increasingly alienated from the

Surrealists and their political squabbles over joining the Communist party. But

he was acutely sensitive to the threat of Fascism which was terrorizing the

people of his own country. His pictures, which he called 'peintures sauvages',

were menaced by violent distortions and aggressive monsters and a terrible

sense of impending catastrophe. Miro was anticipating war.

Miro

was now spending more time in Spain, increasingly alienated from the

Surrealists and their political squabbles over joining the Communist party. But

he was acutely sensitive to the threat of Fascism which was terrorizing the

people of his own country. His pictures, which he called 'peintures sauvages',

were menaced by violent distortions and aggressive monsters and a terrible

sense of impending catastrophe. Miro was anticipating war.

THE OUTBREAK OF CIVIL WAR

In

1936, civil war broke out in Spain, and Mini was forced to return to Paris. The

following year he designed the poster Aidez l’Espagne to be sold for one franc

to help the Spaniards in their struggle for liberty. It showed a Catalan

peasant shaking a swollen and defiant clenched fist. He also painted The Reaper

for the Spanish Republican Government, to hang next to Picasso's Guernica at

the International Exhibition in Paris, and the dramatic Still-Life with an Old

Shoe, in which an apple, symbolizing Spain, is aggressively pierced by the

bayonet-like prongs of a fork.

But

soon the problems of Spain were eclipsed by the shattering events of World War

H. Paris was no longer safe, and Miro found a temporary retreat in a small

cottage, 'Le Clos des Sansonnets', near Varengeville-sur-mer in Normandy, not

far from the house his friend Braque had built for himself a few years before.

'1 was very depressed', Miro later wrote. 'I believed in an inevitable victory

for Nazism and that all that we love and that gives us our reason for living

was sunk forever in the abyss.' Only a few months later, German bombardments

threatened Varengeville and Miro was on the run once more, heading south

through Paris and arriving in Spain just a few days before the Germans marched

into the French capital.

Miro

settled temporarily in Majorca, finding some respite in peaceful hours spent at

the cathedral of Palma, listening to organ recitals and watching the soft light

filtering through the stained-glass windows. In 1942, he took his family back

to Barcelona. His lasting anger at the senseless ravages of war surfaced in

some horrifying lithographs The Barcelona Suite but he also found a vital

creative outlet in ceramic experiments with his childhood friend, Artigas.

By now

his international reputation had grown, particularly in America where his work

was shown regularly at the Pierre Matisse gallery. He made the first of many

trips to America in 1947, invited by the Directors of the Terrace Hilton Hotel

in Cincinnati to paint an enormous mural for their Gourmet Restaurant. This

coincided perfectly with a new desire to communicate with the public and

express himself on a huge scale.

Miro

also visited New York, where the exciting pace of the city and the youthful

optimism of the people gave him a new lease of life and a desire to pick up

with old friends, ending a long period of introspection and detachment. On his

return to Paris in 1948, after eight years' absence, he was given a hero's

welcome and an exhibition of his work at the Galerie Maeght was a resounding

commercial success.

Miro

was soon weighed under with monumental commissions from the Americans, the

French and the Spanish, including paintings and ceramic murals for Harvard

University, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the ceramic Wall of the Sun and

Wall of the Moon for Unesco, Paris, a large monument for the Cervantes Gardens

in Barcelona and, as late as 1970, an enormous ceramic mural for display at

Barcelona airport.

To work

more effectively for the public, Miro increasingly devoted his energies to

lithographs, engravings, etchings and popular crafts ceramic vases and dishes,

for example all of which were much cheaper than easel paintings and could be

widely disseminated. In 1954, he was awarded the Venice Biennale Grand Prize

for engraving, and from the hands of President Eisenhower he received the Grand

International Prize of the Guggenheim Foundation.

THE FOUNDATION MAEGHT

THE FOUNDATION MAEGHT

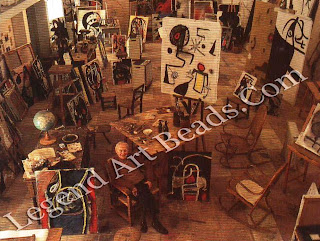

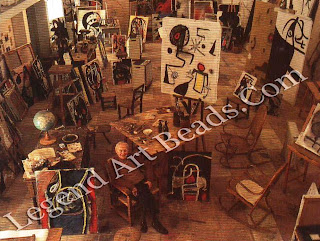

To cope

with the flood of commissions and the time-consuming organization of regular

world-wide exhibitions, the Foundation Maeght was set up in his honour at St

Paul de Vence in 1964 Ceaselessly energetic, Miro spent the last two decades of

his life rushing from Montroig to his printers in Paris, back to Artigas's

kilns in the mountains of Gallifa, and, if he needed to work alone, to the

enormous studio specially built for him by Jose Luis Sert among the terraces

and olive trees of Calamayor neat Palma. This was the only large studio he had

ever owned, but of which he had always dreamed while working in the cramped

conditions of his Paris studios and his tiny room in the Pasaje del Credito,

where he remembered banging his head against the walls when things got too much

for him.

Right

up until his death on 25 December 1983, Miro worked exhaustively, learning the

techniques of monotype when he was 84, and at 86 producing his first

stained-glass windows for the Foundation Maeght. But with an output and a

reputation rivalled only by that of Picasso, the frail, modest old man remained

undazzled by his glory to the end.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Miguel

was unimpressed and in 1910, forced his son to accept a respectable job as a

bookkeeper for a local drugstore. Miro dutifully obeyed, but it broke his

spirit. The tedium of the work and the stifling of his creative energies

brought on an appalling nervous depression, soon compounded by an attack of

typhoid fever, and in desperation his parents sent him to recuperate at their

farm near Montroig in the Catalonian hills. The surrounding landscape made a

lasting impression on the young artist.

Miguel

was unimpressed and in 1910, forced his son to accept a respectable job as a

bookkeeper for a local drugstore. Miro dutifully obeyed, but it broke his

spirit. The tedium of the work and the stifling of his creative energies

brought on an appalling nervous depression, soon compounded by an attack of

typhoid fever, and in desperation his parents sent him to recuperate at their

farm near Montroig in the Catalonian hills. The surrounding landscape made a

lasting impression on the young artist.  These

experiments encouraged Mire to move away from the depiction of everyday reality

in his own work, and to rely instead on his imagination and the hallucinatory

forms and sensations he experienced through extreme hunger. He would sit for

hours staring at the bare walls of his studio and sketching the strange shapes

which appeared in front of his eyes. He did not take drugs himself, and he

remained aloof from the internal squabbles of the group, but he began to

exhibit with the Surrealists, showing his new 'dream paintings' at Pierre

Loeb's gallery and the Galerie Surrealiste.

These

experiments encouraged Mire to move away from the depiction of everyday reality

in his own work, and to rely instead on his imagination and the hallucinatory

forms and sensations he experienced through extreme hunger. He would sit for

hours staring at the bare walls of his studio and sketching the strange shapes

which appeared in front of his eyes. He did not take drugs himself, and he

remained aloof from the internal squabbles of the group, but he began to

exhibit with the Surrealists, showing his new 'dream paintings' at Pierre

Loeb's gallery and the Galerie Surrealiste.  But

Ernst's drunken revelries never soured his friendship with Miro or their

admiration for each other, and occasionally they worked together, both agreeing

to design the costumes and scenery for Diaghilev's ballet, Romeo and Juliet.

Breton, the dogmatic leader of the Surrealist group, violently disapproved of

their involvement in what he considered to be the bourgeois and frivolous world

of ballet. He staged a demonstration in the theatre on the opening night, and

denounced them in his magazine, La Revolution Surrealiste. But Miro had never

bowed to Breton's intellectual dogmas or his authority, preferring to keep his

distance when it suited him.

But

Ernst's drunken revelries never soured his friendship with Miro or their

admiration for each other, and occasionally they worked together, both agreeing

to design the costumes and scenery for Diaghilev's ballet, Romeo and Juliet.

Breton, the dogmatic leader of the Surrealist group, violently disapproved of

their involvement in what he considered to be the bourgeois and frivolous world

of ballet. He staged a demonstration in the theatre on the opening night, and

denounced them in his magazine, La Revolution Surrealiste. But Miro had never

bowed to Breton's intellectual dogmas or his authority, preferring to keep his

distance when it suited him.  Miro

was now spending more time in Spain, increasingly alienated from the

Surrealists and their political squabbles over joining the Communist party. But

he was acutely sensitive to the threat of Fascism which was terrorizing the

people of his own country. His pictures, which he called 'peintures sauvages',

were menaced by violent distortions and aggressive monsters and a terrible

sense of impending catastrophe. Miro was anticipating war.

Miro

was now spending more time in Spain, increasingly alienated from the

Surrealists and their political squabbles over joining the Communist party. But

he was acutely sensitive to the threat of Fascism which was terrorizing the

people of his own country. His pictures, which he called 'peintures sauvages',

were menaced by violent distortions and aggressive monsters and a terrible

sense of impending catastrophe. Miro was anticipating war.

0 Response to "The Great Artist Joan Miro"

Post a Comment