Grunewald

ranks with Direr as the greatest German painter of the Renaissance. After

obscure beginnings, he forged a successful career for himself at the court of

the Archbishop of Mainz, where he was valued not only for his painting, but

also for his skills as an engineer and his services as a courtier. Yet although

he attended the Archbishop at the lavish coronation of Charles V. the artist

himself was an austere character.

Grunewald

specialized in emotive religious scenes which contained a unique blend of

brutal realism, visionary power and brilliant, luminous colouring. The

altarpiece at Isenheim has been acclaimed as the last great painting of the

middle Ages. Grunewald was receptive to new ideas but his attachment to the

Lutheran cause brought about his dismissal from Mainz. He settled in Halle,

where he died of the plague.

The Artist’s Life

Riches to Rags

For most of his career Grunewald enjoyed

the trappings of a successful court painter-yet he died a plague-ridden pauper,

having fallen from official favour because of his religious beliefs.

MATHIS GRUNEWALD

The

painter known to us as Mathis Grunewald was, in fact, called Mathis Gothardt or

Neithardt. The initial error over his name derived from the first biographical

study on him, written in 1675, by the German painter and traveler, Joachim von

Sandrart. Perhaps confusing him with another German artist, Baldung Grien,

Sandrart bestowed on Gothardt the erroneous name which has become his permanent

identity.

Key Dates

c.1474 born in Wurzburg

1504 begins work on his first known

painting, The Mocking of Christ

c.1508-14 court painter to Uriel

von Geminingen, Archbishop of Mainz

c.1512-15 works on The Isenheim

altarpiece

1516- enters service of

Cardinal Albrecht.

1520- attends coronation of

Charles V. Meets DUrer

1520-23 in Halle, advising on

the construction of Albrecht's new collegiate church

1525-26 peasant's revolt. Grunewald

dismissed. Flees to Frankfurt

1527 moves to Halle 1528 dies of

the plague

EARLY CAREER

Grunewald

was born in Wurzburg sometime between 1470 and 1480. Nothing is known about his

early life, other than suggestions that he may have carried out his training in

the studio of Holbein the Elder at Augsburg.

Information

about the initial development of Grunewald’s career is sadly limited and still

hotly disputed. A 'free', that is a qualified, master called Mathis is recorded

at Seligenstadt in 1501 this may be Grunewald. Seligenstadt, situated on the

river Main in northern Bavaria, had no great artistic traditions itself, but it

came within the diocese of the Archbishop of Mainz so, although a fairly small

town, it enjoyed certain privileges. The t; town's charter may have helped

Grunevvald gain access to the Archbishop's court, a powerful source 4 of

patronage in the region. At any rate, this it connection with the Archbishop

had been made By 1504, when Grunewald

began work on The Mocking of Christ for Johan von Cronberg, the representative

of the Archbishop in Ascha ffenburg.

Information

about the initial development of Grunewald’s career is sadly limited and still

hotly disputed. A 'free', that is a qualified, master called Mathis is recorded

at Seligenstadt in 1501 this may be Grunewald. Seligenstadt, situated on the

river Main in northern Bavaria, had no great artistic traditions itself, but it

came within the diocese of the Archbishop of Mainz so, although a fairly small

town, it enjoyed certain privileges. The t; town's charter may have helped

Grunevvald gain access to the Archbishop's court, a powerful source 4 of

patronage in the region. At any rate, this it connection with the Archbishop

had been made By 1504, when Grunewald

began work on The Mocking of Christ for Johan von Cronberg, the representative

of the Archbishop in Ascha ffenburg.

About

1508, Grunewald was appointed court painter to Archbishop Uriel von Gemming.

This was a prestigious post which he held until Uriel's death in 1514. In

recognition of his status, the Archbishop granted him a coat of arms and

presented him with elegant court wear including a shirt with an embroidered

gold collar, a lined purple cloak and yellow kneebreeches.

The

records of Grunewald’s employment with Uriel show that his talents extended

beyond painting. He was a skilled hydraulic engineer and, on several occasions,

was called in to advice on the construction of fountains. Moreover, in his

capacity as the court's leading art official, he was also expected to supervize

new building work. In 1511 he was sent to Aschaffenburg to oversee the

rebuilding of the Archbishop's palace. Shortly afterwards, Grunewald embarked on

the work that was to prove his masterpiece The Isenheim Altarpiece for the

Anthonite Abbey. The Anthonite Order had originated in France at the end of the

11th century and was dedicated to the care of the sick. In particular, it

tended for those suffering from the 'burning sickness' or the plague, for which

St Anthony and St Sebastian (both prominently featured in the altarpiece) were

the protecting saints.

With

the repeated outbreaks of the plague, the Anthonite set .up a series of

hospices at major road junctions in Europe, and the small village of Isenheim,

in Alsace, was chosen as one of these sites because it stood on the important

trade route joining the Rhine Valley and the Mediterranean. , The Preceptor at

Isenheim, Guido Gaersi, had doubtless heard of Grunewald's work for the diocese

of Mainz and commissioned an altarpiece for the hospital chapel. Patients were

taken there ,=5, before receiving medical treatment in the hope that the

intercession of St Anthony might effect a miracle cure or, at the very least,

bring them some spiritual comfort.

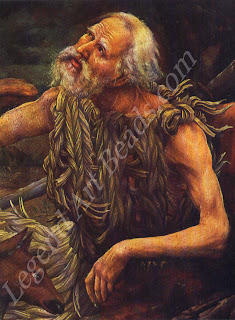

AN AUSTERE REALIST

Grunewald’s

awesomely realistic depiction of the agonies of Christ was unparalleled in

Western art. With its concentration on the physical sufferings shared by the

Lord and the joys of redemption which He offered, it was designed to bolster

the faith of the sick at a time when it might understandably have faltered. In

precisely the same way, the panel illustrating The Temptation of St Anthony showed

the trials of the saint mirrored in the torments of a plague victim. The very

little that we know of Grunewald’s personal life accords well with the austere

nature of the altarpiece. Sandrart tells us that he was a melancholy and

withdrawn character, whose marriage, late in life, proved a most unhappy one.

Grunewald’s

awesomely realistic depiction of the agonies of Christ was unparalleled in

Western art. With its concentration on the physical sufferings shared by the

Lord and the joys of redemption which He offered, it was designed to bolster

the faith of the sick at a time when it might understandably have faltered. In

precisely the same way, the panel illustrating The Temptation of St Anthony showed

the trials of the saint mirrored in the torments of a plague victim. The very

little that we know of Grunewald’s personal life accords well with the austere

nature of the altarpiece. Sandrart tells us that he was a melancholy and

withdrawn character, whose marriage, late in life, proved a most unhappy one.

There

is no concrete evidence to confirm the existence of his wife but Grunewald

certainly had an adopted son called Andreas Neithardt. In fact, the boy's name

is responsible for much of the confusion over Grunewald’s identity, for it

appears that in documents relating to his son, the painter termed himself

'Neithardt' instead of using his own family name. Grunewald completed The

Isenheim Altarpiece by 1515 and within a year had joined the service of the new

Archbishop of Mainz. Uriel's successor, Albrecht of Brandenburg, was an even

more distinguished figure than Grtinewald's earlier benefactor. He had been the

Archbishop of Magdeburg before becoming Bishop and Elector of Mainz and, in

1518, was finally created a cardinal. For a full decade, his patronage kept Grunewald

at the very pinnacle of his proression.

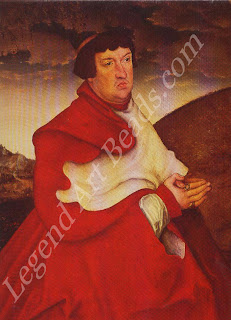

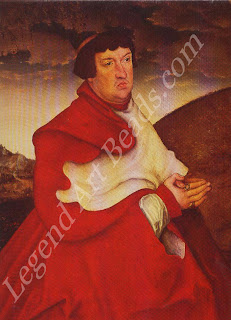

THE CARDINAL'S COURT

Albrecht

employed the artist in much the same manner as his predecessor. In addition to

his painting, Grunewald was required to manage all building projects. From 1520

to 1523, he worked away from home in nearby Halle, where Albrecht was

constructing a new collegiate church. The most impressive of Grtinewald's

surviving works for Albrecht was, in fact, produced for Halle. The Disputation

of St Erasmus and St Maurice formed part of a huge decorative scheme in the new

foundation, which housed over 6000 relics, including the head and bones of St

Erasmus. 5 The commission was a blatant piece of self- , glorification, with

Albrecht portrayed in the guise 1156 of the martyred saint.

Grunewald's

exalted position in the Cardinal's entourage must also have assisted in gaining

him further commissions, such as the one from Canon Reitzmann to depict the

legend of The Miracle of the Snows. The cult had been introduced into Ger-many

by Uriel and Reitzmann had written a study of the subject, dedicated to

Albrecht. In October 1520, Grunewald accompanied the Cardinal to AixlaChappelle

for the coronation of Emperor Charles V. The occasion finally gave him the

opportunity to meet his great compatriot, Albrecht Duren the two men had

previously been involved on the same project The Heller Altarpiece but each had worked on their contributions

quite independently. In his diary, Dilrer recorded that he presented Grunewald

with two florins' worth of his woodcuts and engravings. In contemporary this

was a sizeable gift and illustrates the steem in which he held his fellow

artist.

The

coronation may, hoverer, has had a secondary and less auspicious effect on renewal’s

life. It seems probable that the spectacle of so much wealth and luxury at Aix

appalled the ascetic nature of the painter and encouraged his sympathies for

the growing Protestants cause. In Germany, this movement entered around the

actives of Martin Luther. And; renewal’s later allegiance to the ideals of

rotestantism cannot be disputed. Among the effects found after his death, there

was discovered much Lutheran trash'. This included 27 of other’s sermons, the

possession of which, alone, 'as a punishable offence.

In

addition, there is clear evidence that; Grunewald had already been profoundly

influenced by the mystical writings of St Bridget of weden. This holy woman

spent part of her life in .come, caring for the poor and sick, and speaking, §

us against the corruption of the Pope, whom she penny described as 'a murderer

of souls, like to

In

addition, there is clear evidence that; Grunewald had already been profoundly

influenced by the mystical writings of St Bridget of weden. This holy woman

spent part of her life in .come, caring for the poor and sick, and speaking, §

us against the corruption of the Pope, whom she penny described as 'a murderer

of souls, like to

Mathis Grunewald

Decorative

fountains Grunewald was not simply a talented and successful painter, he was

also a skilled hydraulic engineer. And in his capacity as official artist to

the Archbishop's court Ile was frequently called upon to advice on the

construction of the highly decorative type of fountain which was popular in

16thcentury Germany.

Lucifer

in envy, more unjust than Pilate, more severe than Judas'. Bridget's Revelations

were first published in 1492, and the 1502 edition, issued in Nuremburg with

woodcut illustrations, gained widespread popularity in Germany. Its sombre and

earnest tone probably accounts for much of the intensity and the strange

imagery in Grunewald's work.

THE PEASANTS' REVOLT

The

Protestant troubles came to a head in 1525 with the Peasants' Revolt. Similar

insurrections had occurred before, but never on such a vast scale. Nearly the

whole of southern Germany was affected, with castles and monasteries looted and

their occupants slaughtered. Initially, Luther lent his backing to the

uprising, issuing 'Twelve Articles' in support of the peasant's claims copies

of which were also found among Grunewald’s belongings. However, as the

bloodshed increased, he reversed his position and condemned the rebels as

murderers and thieves. The diocese of Mainz did not escape the violence. In

Halle, there were riots and Cardinal Albrecht's t life was only saved by the intervention

of his chaplain, Winkler, who had Protestant connections. In Aschaffenburg, the

Archbishop's representative was forced to surrender to the ;71 marauding

rebels.

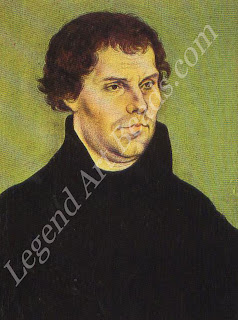

Grunewald

was deeply influenced by two powerfully religious figures - St Bridget of

Sweden and Martin Luther. Bridget, an intense and mystical woman, recorded her

visions, which dwelt on the physical sufferings of Christ, in her Revelations. Grunewald

knew the 1502 edition; published by a relative of airier. Its sombre woodcuts

influenced his work and its criticism of church corruption fuelled his

sympathies to the teachings of Luther which were gaining popularity all over

Germany.

Lucifer

in envy, more unjust than Pilate, more severe than Judas'. Bridget's

Revelations were first published in 1492, and the 1502 edition, issued in

Nuremburg with woodcut illustrations, gained widespread popularity in Germany.

Its sombre and earnest tone probably accounts for much of the intensity and the

strange imagery in Grunewald's work.

THE PEASANTS' REVOLT

The

Protestant troubles came to a head in 1525 with the Peasants' Revolt. Similar

insurrections had occurred before, but never on such a vast scale. Nearly the

whole of southern Germany was affected, with castles and monasteries looted and

their occupants slaughtered.

Initially,

Luther lent his backing to the uprising, issuing 'Twelve Articles' in support

of the peasant's claims - copies of which were also found among Grunewald’s

belongings. However, as the bloodshed increased, he reversed his position and

condemned the rebels as murderers and thieves. The diocese of Mainz did not

escape the violence. In Halle, there were riots and Cardinal Albrecht's t life

was only saved by the intervention of his chaplain, Winkler, who had Protestant

connections. In Aschaffenburg, the Archbishop's representative was forced to

surrender to the; 71 marauding rebels.

These

successes were short lived. Within months, the uprising was suppressed and the

inevitable reprisals followed, during which thousands of rebel peasants were

summarily executed. In 1526, Albrecht returned to Aschaffenburg to preside over

the trials of some of the insurgents. Participants in the rioting were harshly

dealt with and those under suspicion were dismissed from his service.

Seligenstadt lost its charter and the local guilds were deprived of their

ancient privileges. Grunewald, as a knowing sympathizer, was among those

dismissed. He received his final payment in February 1526. The same year Simon

Franck replaced him as court painter.

THE ROAD TO RUIN

Perhaps

fearing further punishment, Grunewald fled to Frankfurt. This was a logical

choice for, as a free imperial city, Frankfurt must have seemed a safe haven

from the jurisdiction of Mainz. Before leaving, Grunewald arranged the apprenticeship

of his son, Andreas, to Arnold Rucker, a carver and cabinet-maker. It is

possible that this Rucker had shared his studio in Seligenstadt. Alhdreas

himself is documented up until 1552, when he was recorded seeking official

permission to teach in a school in Frankfurt.

The

last few years of Grunewald's career were a Miserable period, in which, as far

as can. Be gathered, he was scarcely able to paint and was compelled to scratch

together a meager living through an assortment of menial jobs. In Frankfurt, he

stayed at 'the Unicorn', the house of a silk-embroiderer called Hans von

Saarbrucken. While resident there, Grunewald’s principal occupation was as a

salesman of artist's colours and of a curative balm, the formula for which he

had presumably learnt from his friends at the hospital in Isenheim. He also

received a commission from the city of Magdeburg to produce technical drawings

of the mills situated along the river Main. However, it appears that Grunewald

left Frankfurt before this task was completed. In the summer of 1527, Grunewald

became convinced that he was being spied upon and that his life was in danger.

He therefore drew up his will and fled from Frankfurt to Halle where a

sympathetic town magistrate who shared his Lutheran views employed him as a

hydraulic engineer. But this was a very brief interlude.

The

last few years of Grunewald's career were a Miserable period, in which, as far

as can. Be gathered, he was scarcely able to paint and was compelled to scratch

together a meager living through an assortment of menial jobs. In Frankfurt, he

stayed at 'the Unicorn', the house of a silk-embroiderer called Hans von

Saarbrucken. While resident there, Grunewald’s principal occupation was as a

salesman of artist's colours and of a curative balm, the formula for which he

had presumably learnt from his friends at the hospital in Isenheim. He also

received a commission from the city of Magdeburg to produce technical drawings

of the mills situated along the river Main. However, it appears that Grunewald

left Frankfurt before this task was completed. In the summer of 1527, Grunewald

became convinced that he was being spied upon and that his life was in danger.

He therefore drew up his will and fled from Frankfurt to Halle where a

sympathetic town magistrate who shared his Lutheran views employed him as a

hydraulic engineer. But this was a very brief interlude.

In

September 1528, while staying with the silk weaver Hans Plock, Grunewald died

of the plague. The inventory of his belongings emphasized the abrupt decline in

his fortunes. A bed was the only piece of furniture he owned. Beyond this,

there were only some books, his painting materials and a variety of court garments

a sad reminder of his former status. Grunewald was buried outside the city

walls, without a stone to mark his resting place. In a few years, this was

overgrown and the location swiftly forgotten.

Writer- A Marshall Cavendish

Information

about the initial development of Grunewald’s career is sadly limited and still

hotly disputed. A 'free', that is a qualified, master called Mathis is recorded

at Seligenstadt in 1501 this may be Grunewald. Seligenstadt, situated on the

river Main in northern Bavaria, had no great artistic traditions itself, but it

came within the diocese of the Archbishop of Mainz so, although a fairly small

town, it enjoyed certain privileges. The t; town's charter may have helped

Grunevvald gain access to the Archbishop's court, a powerful source 4 of

patronage in the region. At any rate, this it connection with the Archbishop

had been made By 1504, when Grunewald

began work on The Mocking of Christ for Johan von Cronberg, the representative

of the Archbishop in Ascha ffenburg.

Information

about the initial development of Grunewald’s career is sadly limited and still

hotly disputed. A 'free', that is a qualified, master called Mathis is recorded

at Seligenstadt in 1501 this may be Grunewald. Seligenstadt, situated on the

river Main in northern Bavaria, had no great artistic traditions itself, but it

came within the diocese of the Archbishop of Mainz so, although a fairly small

town, it enjoyed certain privileges. The t; town's charter may have helped

Grunevvald gain access to the Archbishop's court, a powerful source 4 of

patronage in the region. At any rate, this it connection with the Archbishop

had been made By 1504, when Grunewald

began work on The Mocking of Christ for Johan von Cronberg, the representative

of the Archbishop in Ascha ffenburg. Grunewald’s

awesomely realistic depiction of the agonies of Christ was unparalleled in

Western art. With its concentration on the physical sufferings shared by the

Lord and the joys of redemption which He offered, it was designed to bolster

the faith of the sick at a time when it might understandably have faltered. In

precisely the same way, the panel illustrating The Temptation of St Anthony showed

the trials of the saint mirrored in the torments of a plague victim. The very

little that we know of Grunewald’s personal life accords well with the austere

nature of the altarpiece. Sandrart tells us that he was a melancholy and

withdrawn character, whose marriage, late in life, proved a most unhappy one.

Grunewald’s

awesomely realistic depiction of the agonies of Christ was unparalleled in

Western art. With its concentration on the physical sufferings shared by the

Lord and the joys of redemption which He offered, it was designed to bolster

the faith of the sick at a time when it might understandably have faltered. In

precisely the same way, the panel illustrating The Temptation of St Anthony showed

the trials of the saint mirrored in the torments of a plague victim. The very

little that we know of Grunewald’s personal life accords well with the austere

nature of the altarpiece. Sandrart tells us that he was a melancholy and

withdrawn character, whose marriage, late in life, proved a most unhappy one.  In

addition, there is clear evidence that; Grunewald had already been profoundly

influenced by the mystical writings of St Bridget of weden. This holy woman

spent part of her life in .come, caring for the poor and sick, and speaking, §

us against the corruption of the Pope, whom she penny described as 'a murderer

of souls, like to

In

addition, there is clear evidence that; Grunewald had already been profoundly

influenced by the mystical writings of St Bridget of weden. This holy woman

spent part of her life in .come, caring for the poor and sick, and speaking, §

us against the corruption of the Pope, whom she penny described as 'a murderer

of souls, like to  The

last few years of Grunewald's career were a Miserable period, in which, as far

as can. Be gathered, he was scarcely able to paint and was compelled to scratch

together a meager living through an assortment of menial jobs. In Frankfurt, he

stayed at 'the Unicorn', the house of a silk-embroiderer called Hans von

Saarbrucken. While resident there, Grunewald’s principal occupation was as a

salesman of artist's colours and of a curative balm, the formula for which he

had presumably learnt from his friends at the hospital in Isenheim. He also

received a commission from the city of Magdeburg to produce technical drawings

of the mills situated along the river Main. However, it appears that Grunewald

left Frankfurt before this task was completed. In the summer of 1527, Grunewald

became convinced that he was being spied upon and that his life was in danger.

He therefore drew up his will and fled from Frankfurt to Halle where a

sympathetic town magistrate who shared his Lutheran views employed him as a

hydraulic engineer. But this was a very brief interlude.

The

last few years of Grunewald's career were a Miserable period, in which, as far

as can. Be gathered, he was scarcely able to paint and was compelled to scratch

together a meager living through an assortment of menial jobs. In Frankfurt, he

stayed at 'the Unicorn', the house of a silk-embroiderer called Hans von

Saarbrucken. While resident there, Grunewald’s principal occupation was as a

salesman of artist's colours and of a curative balm, the formula for which he

had presumably learnt from his friends at the hospital in Isenheim. He also

received a commission from the city of Magdeburg to produce technical drawings

of the mills situated along the river Main. However, it appears that Grunewald

left Frankfurt before this task was completed. In the summer of 1527, Grunewald

became convinced that he was being spied upon and that his life was in danger.

He therefore drew up his will and fled from Frankfurt to Halle where a

sympathetic town magistrate who shared his Lutheran views employed him as a

hydraulic engineer. But this was a very brief interlude.

0 Response to "Introduction to German Great Artist – Mathis Grunewald"

Post a Comment