Netherlandish Great Artist Jan Van Eyck - The Port of Bruges

Posted by

Art Of Legend India [dot] Com

On

2:04 AM

Now a

town of quiet tree-lined canals and fine medieval architecture, Bruges once led

a very different life it was the trading centre of the whole of north-west

Europe.

On a

January day in 1430, the Flemish city of Bruges was on its best behaviour.

Thousands of its citizens lined the narrow streets, jostling and straining to

catch a glimpse of the Princess Isabella of Portugal as she passed by. She had

arrived from her homeland to be with her future husband, Duke Philip the Good

of Burgundy.

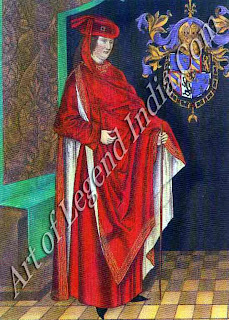

Among

the Duke's enormous entourage that day was no less than 40 varlets de chamber.

One of them was Jan van Eyck. For the last part of his life, Van Eyck was based

in Bruges, a port on the Zwijn River, almost 10 miles inland from the North Sea.

His works helped to characterize the city as the cradle of Flemish painting.

But Bruges had already won an enviable reputation as a major centre of the

medieval cloth industry, and as the main international emporium of north-west

Europe.

As one

French chronicler noted, when describing that royal entry of 1430, Bruges was

'thronged with visitors from foreign lands . . . a centre for merchandise and a

meeting-place for those of other lands, where pass greater quantities of goods

than, perchance, in any other city of Europe'. The chronicler added, 'and a

great shame it would be if ever Bruges were destroyed. .

In

subsequent centuries Bruges declined, but it never was destroyed. Thus the city

of Van Eyck's era has not completely disappeared from view. Many of the homes

of the medieval bourgeoisie are still standing tall, thin houses, mostly built

of brick, subtly decorated with pink or grey sandstone, white stone from

Brabant or blue Tournai limestone. Their large rooms are lit by spacious

windows, which once allowed the householder's prized oil paintings to be seen

to their best advantage. The old Market Hall can still be identified from afar

by its distinctive belfry. The Town Hall, the Church of Notre Dame and the

Beguinage a retreat for secular nuns all survives to recall the city's former

prosperity.

Yet

this tangible legacy can easily mislead. The quiet canals and the dignified

Gothic architecture create an atmosphere of tranquillity, even of serenity. But

this belies the turmoil of the city's early history, when its citizens fiercely

resisted the efforts of Flemish counts and French kings to subdue them; in

their halcyon days the Three Members from Flanders' Bruges, Ghent and Ypres

virtually governed the province between them. Bruges was no quaint medieval

backwater. It was a tumultuous commercial city, where merchants from 17 nations

operated, and 20 states were represented by official ministers.

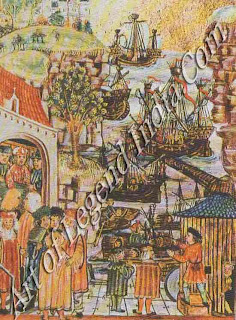

In

medieval times, the continent comprised two main commercial zones that of the

Baltic and the North Sea, and that of the Mediterranean. Bruges began to

prosper as a textile centre within the northern zone, and also as a convenient

port for the commercial traffic between England and Flanders. As the Flemish

cloth industry came to rely more and more heavily on English supplies of wool,

so the trade of Bruges expanded rapidly.

The

port then evolved into something far more than a simple Anglo-Flemish trade

junction. Germans, Normans, Bretons and Spaniards came in increasing numbers to

buy and sell at Bruges's annual fair, established in 1200. Before the end of

the 13th century, the great galleys of Genoa and Venice were heading regularly

for the northern port. So at a time when land communications were unreliable,

Bruges became the destination of seaborne merchants from both the northern and

southern commercial centres of Europe.

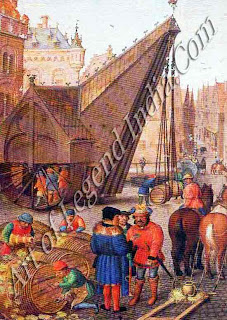

The

native Flemings did not themselves develop as international merchants. Instead,

the foreign community of Bruges grew larger and it became a truly cosmopolitan

city. Its prosperity came to rely not on intermittent fairs, but on permanent

trade. Merchandise was sent there for distribution in all directions and the

commodities which found their way on to the quayside came from around the

world. There were Russian furs, northern cloths, wines from Burgundy, Bordeaux

and the Rhine, and metals from Germany. There was wool, tin and cheeses from

England, butter and pigs from Denmark, corn from Prussia, and salt fish and

dried fish from Norway. And there was Baltic timber in abundance, and fruit

from Spain. Perhaps the most exotic goods were those stocked in the warehouses

of the spice-importers, cinnamon from Ceylon, cloves from the Molucca Islands,

mace from Arabia not forgetting the saffron, cinnabar, ivory and oil of white

poppy which were used as artists' materials.

Such a

thriving commercial centre naturally attracted businessmen. By 1369 there were

15 separate 'merchant banks' there. Italian bankers and money-lenders were keen

to establish their northern branches in the city. In 1469, the Medici of

Florence had a staff of eight at Bruges, one of whom was responsible for

purchases of cloth and wool, while another had the duty of selling silks and

velvets to the Burgundian court. Giovanni Arnolfini, whose wedding portrait was

painted by Van Eyck, was himself an Italian expatriate from Lucca. He was one

of the leading importers of alum, a substance essential for the dyeing of wool.

Germans

as well as Italians found the city to be a profitable home-from-home. Bruges

was one of the Hanseatic League's overseas trading posts, along with London,

Bergen and Novgorod. The League had been formed by German merchants to give

political backing to their trading agreements. The trading posts, or kontore,

were independent from their host country. Within them, members were under the

jurisdiction of German law; houses, offices and warehouses were all corporately

owned and here the League members lived and traded.

Communities

of foreign merchants at this time, were often encouraged to live in a

particular area of a city, separate from the native citizens. In Bruges,

however, the Hanseatic League were not confined to specific quarters of the

city but lived among the Flemings. Elsewhere in northern Europe, these

privileged German League communities often encountered native resentment, but

their kontore was welcomed in Bruges and seen as a source of extra trade and

revenue, increasing the city's prosperity.

A large

proportion of the citizens, however, did not share in the general affluence.

They had to endure the rigours and squalor of medieval urban life as best they

could. 'This is no place for poor people', wrote Tafur of Seville, a

scandalized visitor, in 1435. He also commented with disapproval on the

bourgeoisie, with their 'baths for men and women in common, a practice which

they look on as normal and decent as we do going to Mass. There is no doubt he

went on, 'that there is considerable licence . . .' He probably noticed local

zeal for alcohol too in 1420 the annual consumption of wine per head of the

population was 100 litres.

There

were certainly plenty of opportunities to over-indulge on occasions such as the

24 great tournaments held at Bruges between 1405 and 1482 for example. Those

well-heeled burghers, who liked to have themselves depicted in attitudes of

pious austerity, also revelled in their conspicuous consumption. Bruges in the

mid 15th century was, however, a city that had already started to decline. The

river Zwijn began to silt up during the 14th century. By 1490 it was completely

blocked and Bruges then ceased to be an important port commercially, although

it flourished artistically under the Dukes of Burgundy.

By

1500, Antwerp had taken over the commercial mantle and some people began to

talk of 'Bruges le mort' (Bruges the dead). But it could almost be said that

its great painters at this time had already conferred a kind of immortality on

the city.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Netherlandish Great Artist Jan Van Eyck - The Port of Bruges"

Post a Comment