Miro

was an extremely versatile, inventive and prolific artist. His career does not

show any steady evolution of style, but rather an unquenchable thirst for

experiment, a tireless ability to absorb and transform new influences, and an

imaginative response to the varied qualities of the differing materials with

which he worked. Miro himself commented on the element of uncertainty and lack

of premeditation in his creative processes, writing 'It is difficult for me to

speak of my painting, for it is always born in a state of hallucination,

provoked by some shock or other, objective or subjective, for which I am

entirely unresponsible', and although he later modified the views in this

statement (made in 1933) it gives an indication of the fascinating unpredictability

of his work. It ranges from the loving detail of Kitchen Garden with a Donkey

to the daringly empty abstract forms of Blue III, from the mischievous

playfulness of Harlequin's Carnival to the bitter anger of Aidez l'Espagne. And

Mire's genius was such that he was just as happy working on a fairly small

scale in the medium of lithography as he was creating huge decorative murals.

Both satisfied his urge to create an art which belonged to the public at large,

by-passing the exclusivity of the museums.

This

is one of the first paintings in which Mini worked in the style to which a

friend gave the name 'detallista', characterized by great attention to detail

and sharpness of focus from foreground to background. The overall feeling,

however, is not naturalistic, for the stylized forms and the rhythmic patterns

made by, for example, the lines of cultivation and the branches against the

sky, produce an effect somewhat like a complex stage set. Miro holds together

the diverse elements with consummate skill, and the bright colours and clear

forms convey with great vividness the heat of his native Catalonia.

This

is one of the first paintings in which Mini worked in the style to which a

friend gave the name 'detallista', characterized by great attention to detail

and sharpness of focus from foreground to background. The overall feeling,

however, is not naturalistic, for the stylized forms and the rhythmic patterns

made by, for example, the lines of cultivation and the branches against the

sky, produce an effect somewhat like a complex stage set. Miro holds together

the diverse elements with consummate skill, and the bright colours and clear

forms convey with great vividness the heat of his native Catalonia.

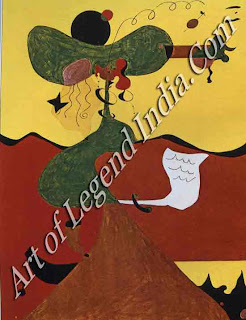

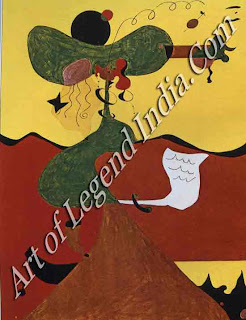

In

1938, Miro wrote an article in which he described the geitesis of this

painting, one of his most famous works and one of the first in which he

revealed his unmistakable personal style. At the time, he was experiencing a

period of great hardship and he wrote 'For Harlequin's Carnival I made many

drawings in which I expressed my hall my hallucinations brought on by hunger. I

came home at night without honing dined and noted my sensations on payer. A

room with a window and table are indicated and they belong more or less to the

everyday world, but alter that Miro's imagination takes over. A bizarre

assembly of insect-like creatures play dance and make music, one of them having

the suggestion of a human face with a ridiculous moustache. It has been said

that Miro's vision at this painting is essentially childlike, but the skill

with which he unifies the flow of movement and incident is that of a highly

sophisticated artist.

In

1929, Miro made a series of four 'Imaginary Portraits' based on paintings of

the past; this one was inspired by an engraving of a portrait by the minor

English painter George Engleheart (1752-1829). The head and neck of the sitter

are reduced to little more than cipher underneath the dominating form other

broad-brimmed hat.

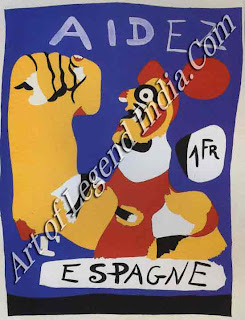

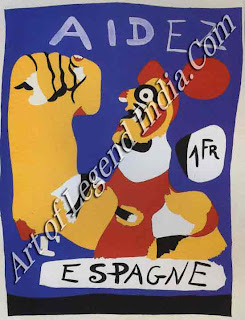

Miro

felt despair at the Spanish Civil War and he produced this silk-screen print to

be sold in aid of relief for his native country the price of one franc is a

bold part of the design. The powerfully conceived figure is shown clenching a

massive fist in the Loyalist salute and the inscription tells of the 'immense

creative resources' of the people of Spain.

Miro

felt despair at the Spanish Civil War and he produced this silk-screen print to

be sold in aid of relief for his native country the price of one franc is a

bold part of the design. The powerfully conceived figure is shown clenching a

massive fist in the Loyalist salute and the inscription tells of the 'immense

creative resources' of the people of Spain.

On

his return to Paris from America, Miro produced a great number of paintings in

two complementary styles which have been described as 'slow paintings' and

'quick paintings'. This light-hearted work belongs to the former category, with

its careful delineation of shapes and forms and its dense application of bright

primary colour.

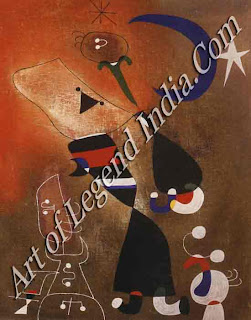

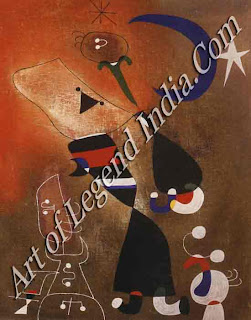

Miro

was haunted by the theme of the night, the time for dreams, silence and

solitude and for mystic communion with the stars. His nocturnal landscapes are

often inhabited by women, who sway in the moonlight, and 'birds of the night'

symbols of the flight of the spirit from the waking consciousness of day.

Miro

was haunted by the theme of the night, the time for dreams, silence and

solitude and for mystic communion with the stars. His nocturnal landscapes are

often inhabited by women, who sway in the moonlight, and 'birds of the night'

symbols of the flight of the spirit from the waking consciousness of day.

Miro's

decorative style was well adapted to work on a large scale and he liked the

challenge of painting for a specific public place. This mural almost 20 feet

wide was painted for the dining room of the Harkness Commons building at

Harvard University, at the suggestion of the great architect Walter Gropius.

Miro executed the painting in Barcelona and it was installed in 1951, but in

the next few years it was found that it was deteriorating and Miro proposed

that a ceramic version should be substituted. Miro described the subject cryptically

as 'of a moralistic and poetic significance', but some commentators have

suggested that it shows a bullfight scene. In the centre of the composition is

a bull, with two enormous black horns and the enlarged sexual organs so often

seen in Miro`s work.

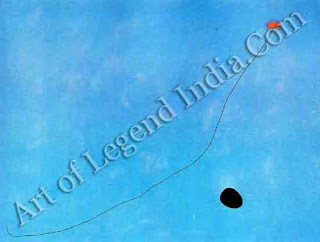

This

is the last in a series of three similar paintings (Blue I, II and III) flint

Mira executed in 1961. It illustrates the great range of Miro's imagination,

for whereas many of his best-known works are comparatively small and crowded

with restlessly moving incident and detail, this one is huge and serenely

sparse. It has links with some of his more characteristic works, however, in

the strange, amoeba-like form that trails across the blue void, suggesting the

immensity and mysteries of the universe. The blue itself-one of Miro's

favourite colours was described by his early champion, Rene Gaffe, as 'a savage

blue, insolent, electric, which sufficed by itself to make the canvas vibrate'.

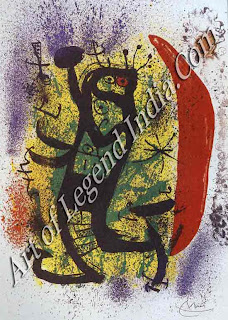

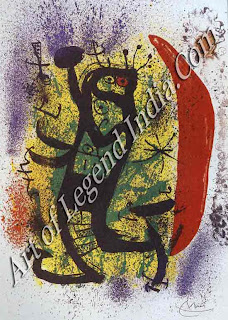

Miro

was one of the greatest graphic artists the 20th century has seen, excelling

particularly at lithography the making of prints from a specially prepared

stone surface. This is one of a series of ten prints by Miro and nine other

artists published as a portfolio to benefit the Swiss Centre for Clinical

Research on Cancer.

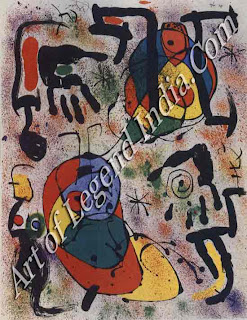

This

is one of a series of six lithographs entitled 'Seers'. A seer is a prophet or

someone who has the power to see into the future, and the handprints here

allude to the idea of palm-reading. The bright colours, spattered background

and whirling shapes suggest the state of ecstasy which the seer must enter in

order to transcend earthly experience.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

This

is one of the first paintings in which Mini worked in the style to which a

friend gave the name 'detallista', characterized by great attention to detail

and sharpness of focus from foreground to background. The overall feeling,

however, is not naturalistic, for the stylized forms and the rhythmic patterns

made by, for example, the lines of cultivation and the branches against the

sky, produce an effect somewhat like a complex stage set. Miro holds together

the diverse elements with consummate skill, and the bright colours and clear

forms convey with great vividness the heat of his native Catalonia.

This

is one of the first paintings in which Mini worked in the style to which a

friend gave the name 'detallista', characterized by great attention to detail

and sharpness of focus from foreground to background. The overall feeling,

however, is not naturalistic, for the stylized forms and the rhythmic patterns

made by, for example, the lines of cultivation and the branches against the

sky, produce an effect somewhat like a complex stage set. Miro holds together

the diverse elements with consummate skill, and the bright colours and clear

forms convey with great vividness the heat of his native Catalonia.

0 Response to "The Spainish Great Artist - Joan Miro Painting Gallery"

Post a Comment