Religious Visions

Neglected

for hundreds of years, Grunewald has now been recognised as a master. The

passion and intensity of his work gives powerful impact to his paintings, all

with religious themes.

Grunewald

is an isolated figure in the history of German art. His very individual style

of painting betrays no close allegiance to any of the masters of his age, he

left no known pupils or followers, and his descent into obscurity was both

rapid and complete. When, in 1597, Emperor Rudolph II tried to acquire The

Isenheim Altarpiece, the artist's identity was already unknown and, as late as

1852, The Miracle of the Snows was sold at a derisory price as a mediocre work

by an anonymous artist.

One

theory put forward to explain this neglect is that contemporary observers

deliberately ignored Grunewald because of his Lutheran beliefs. Much more

significant, however, was the fact that most unusually for this period he

produced little or no engraved work. In an age when travel was not always easy

and few people might, for example, be willing to risk a visit to a plague

hospital where The Isenheim Altarpiece was sited to see a work of art, this

drastically reduced the scope of his influence.

In

addition, Grunewald chose not to devote his studies to the new world of

possibilities that was being opened up by the Renaissance. His art was firmly centered

on God, not man. The small body of his surviving work is comprised entirely of

religious paintings, even though it is clear from his depiction of Cardinal

Albrecht as St Erasmus that he could have made a healthy living as a

portraitist. Certainly, he was aware of some of the technical developments

achieved by the Italians the laws of perspective and anatomy, in particular but

he used them only as minor components in his pictures.

Most of

Grunewald's commissions were for altarpieces. By the late Gothic period, these

had become complex but adaptable structures, in which the movable panels

enclosed sculpted figures and were crowned with richly carved canopies. The

painted sections included folding wings, which could be opened or shut to suit

the liturgical cycle of church feasts, and a detachable panel at the foot of

the picture, called a predella.

A COMPLEX MASTERPIECE

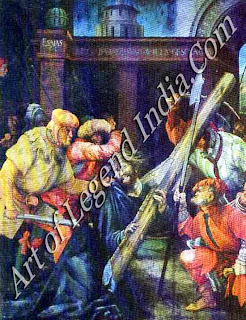

The

Isenheim Altarpiece was one of the most elaborate examples of this format ever

produced. The inner section, with its statues of saints by Niklaus von

Haguenau, was executed quite independently from Grunewald's contribution. His

work consisted of various panels including a double set of folding wings, which

allowed three separate combinations of pictures to be shown at different times

of year. Thus, the altarpiece would be closed during Easter week, when the

bleak Crucifixion symbolized the church's mourning; was opened for most of the

year, to show the joyous scenes of the Annunciation and the Resurrection; and

displayed the final variant, with incidents from the life of St Anthony, on the

feast day of the Order's patron saint.

The

status of artists at this time was that of craftsmen, rather than of creative

individuals. Patrons and especially religious patrons would choose the subjects

to be illustrated and would often sketch out a plan of the composition. Within

these restraints, however, Grunewald found a great deal of freedom to produce

his unique brand of expressive realism. 'A barbarian and a theologian', one

commentator called him, neatly identifying the contradictory strands of his

art.

Certain

Gothic elements remained in Grunewald's work. The use of a larger-than-life

Christ in scenes of the Passion was a distinctly medieval feature, and the

presence of John the Baptist at the Isenheim Crucifixion and the curious

angelic orchestra serenading the Virgin, proved that these were contemplative

works rather than naturalistic illustrations of Biblical events.

However,

Grunewald allied these intellectual compositions to an unprecedented show of

realism, in a bid to tie emotional and rational responses into a firm bond of

faith. To this end, he made use of expressionistic distortions to heighten the

graphic power of his paintings. In his Crucifixions, for example, Christ's feet

are stretched into a deformed arc; the fingers claw convulsively at the surrounding

blackness; and the flesh is livid, discoloured and flecked with thorny wounds.

The rough-surfaced beam of the cross is slightly curved and the arms of Christ

painfully rigid, so that the body looks like a helpless arrow on a giant bow.

EXPRESSIVE COLOURS

An even

more potent weapon in Grunewald's artistic armoury was his vibrant colouring,

which could evoke the full gamut of human emotions, from the depths of despair

to the glory of the sublime. In all his versions of the Crucifixion, he

employed dark, sketchy backgrounds and pallid, bloodless figures, setting them

off with patches of incandescent colour, to create an eerie, mournful effect.

An even

more potent weapon in Grunewald's artistic armoury was his vibrant colouring,

which could evoke the full gamut of human emotions, from the depths of despair

to the glory of the sublime. In all his versions of the Crucifixion, he

employed dark, sketchy backgrounds and pallid, bloodless figures, setting them

off with patches of incandescent colour, to create an eerie, mournful effect.

By

contrast, his scenes of the Madonna and Child and the Annunciation glow with a

luminous joy, and the Isenheim Resurrection is a particular triumph. In most

contemporary treatments of this theme, Christ steps sedately out of his tomb

without waking the sleeping soldiers. In Grunewald's version, however, the

Saviour's Resurrection and his Ascension are combined in an explosion of light.

The guards are hurled aside like worthless dummies and Christ ascends to Heaven

encircled by a halo whose rainbow colours are reflected in his clothes.

Artists

usually prepared their own paints at this period, and were careful not to

divulge their methods. In later life, Grunewald was obliged to sell his paints

for a brief time and it is a measure of the quality of his colours that, after

his death in Halle, the city's official artist, Hans Hamburger, was called in

to analyze them. Unfortunately, he was unable to work out the formula and the

secret died with Grunewald.

Attempts

have been made to find an echo of Grunewald's individual style in the paintings

of his contemporaries of the Danube school. But the violence of Grunewald's

effects leaves them far behind and it is no accident that his work was

rediscovered in the 20th century, during the heyday of the German

Expressionists.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

An even

more potent weapon in Grunewald's artistic armoury was his vibrant colouring,

which could evoke the full gamut of human emotions, from the depths of despair

to the glory of the sublime. In all his versions of the Crucifixion, he

employed dark, sketchy backgrounds and pallid, bloodless figures, setting them

off with patches of incandescent colour, to create an eerie, mournful effect.

An even

more potent weapon in Grunewald's artistic armoury was his vibrant colouring,

which could evoke the full gamut of human emotions, from the depths of despair

to the glory of the sublime. In all his versions of the Crucifixion, he

employed dark, sketchy backgrounds and pallid, bloodless figures, setting them

off with patches of incandescent colour, to create an eerie, mournful effect.

0 Response to "German Great Artist Mathis Grunewald - Religious Visions "

Post a Comment