EDVARD

MUNCH

1863-1944

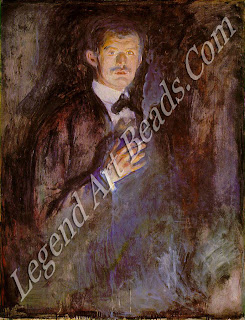

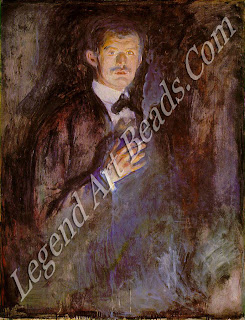

Edvard

Munch was Norway's greatest painter and graphic artist, a major exponent of

Symbolism and a forerunner of the Expressionists. The tragic loss of his mother

and sister in his childhood brought a morbid tone to much of his work.

Initially, his friendship with the bohemian circle in the Norwegian capital

steered him towards Impressionism, but trips to Paris from 1889 onwards put him

in touch with the Symbolists.

In

1892, Munch's name was made when his exhibition in Berlin was closed down,

bringing him instant notoriety. Settling in Germany, he embarked on his Frieze

of Life, a compilation of intensely personal images of love and death.

Overwork, alcohol and emotional strain led Munch to a nervous breakdown in

1908. After this, he returned to live in seclusion in Norway, devoting his last

years to public murals and studies of workers.

THE EDVARD MUNCH 'S LIFE

A Mind in Torment

Traumatic

childhood experiences created in Munch a chronic anxiety and restlessness,

leading ultimately to a nervous breakdown. After this, he returned to his

native Norway to recuperate and settle.

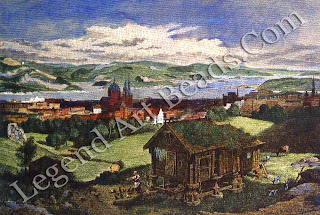

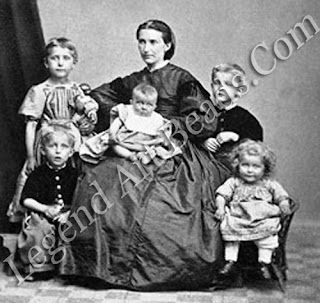

Edvard

Munch was born on 12 December 1863, in Loten, a small farming community in

southern Norway. His father, Christian, came from a professional background of

churchmen and soldiers and worked as a military physician. Christian's brother,

Peter Andreas Munch, was a celebrated historian.

Edvard

was the second son of five children. A year after his birth, the family moved

to the capital, Christiania (re-named Oslo in 1927), where tragedy was to enter

their lives. In 1868, Munch's mother died of tuberculosis at the age of 33 and,

in 1877, his favourite sister Sophie also perished from the same disease. These

early misfortunes scarred the boy deeply, and throughout his long career,

images of the sick room and the deathbed recur constantly in his work.

Munch's

home life was claustrophobic and oppressive. A sickly child himself, he was

confined within the family flat for considerable periods of his youth, while

his father's religious fervour, which had intensified after the death of his

wife, was bringing him to the brink of insanity for hours at a tune, he would

pace up and down his room in prayer. Small wonder that Munch later wrote of his

childhood, 'Illness, madness and death were the black angels that kept watch

over 6 my cradle and accompanied me all my life.

Fortunately,

his aunt Karen had taken over the running of the family and was to prove a stabilizing

influence. As an amateur painter, she encouraged the Munch children to draw.

Accordingly, Edvard made copies of the illustrations in Grimm's fairy tales

and, in the early 1880s, was trying to sell his work to magazines.

Key Dates

1863 born in Loten, southern

Norway

1868 mother dies

1877 sister dies

1881-3 attends State School of

Art and Crafts

1885/6 paints The Sick

Child

1889-91 scholarship to study in

Paris

1892 Berlin exhibition closed

1906 designs theatre sets for

lbsen's Ghosts

1908 suffers a nervous

breakdown

1909 settles in Norway

1916 his murals installed at

Christiania (Oslo) University

1937 his paintings confiscated by

the Nazis

1944 dies at Ekely

By this

time, he had already decided on art as a career. His studies in engineering at

the Technical College had lasted less than a year and, in 1881, he entered the

State School of Art and Crafts. His initial supervisor there was Julius

Middelthun, but the dominant influence on his early development was the

naturalist painter, Christian Krohg. In 1882, along with six other artists,

Munch rented a studio where Krohg provided informal instruction.

By this

time, he had already decided on art as a career. His studies in engineering at

the Technical College had lasted less than a year and, in 1881, he entered the

State School of Art and Crafts. His initial supervisor there was Julius

Middelthun, but the dominant influence on his early development was the

naturalist painter, Christian Krohg. In 1882, along with six other artists,

Munch rented a studio where Krohg provided informal instruction.

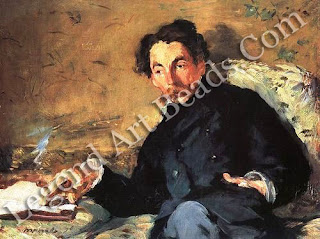

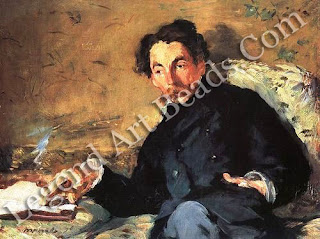

Through

Krohg, Munch also came into contact with the bohemian circle of writers and

painters who were in the forefront of artistic rebellion in Norway. Led by

Krohg and the novelist Hans Jaeger, the group denounced bourgeois morality and

pressed for radical, sexual and artistic freedom. In literature, they

worshipped Zola and, in painting, they advocated an unstinting brand of

realism. One commentator summed them up as 'that half-debauched,

poverty-stricken, Christiania gypsy camp'.

Norway,

however, was too provincial a platform for Munch's talents. In 1883, he

attended the open-air academy run by Gauguin's brother-in-law, Frits Thaulow,

and through him gained a travel grant to Paris two years later. The visit

lasted only three weeks, but gave him the opportunity to see most of the latest

works by Monet and the Impressionists.

Some

Parisian influences can be detected in Munch's first masterpiece, The Sick

Child, which was completed in 1886. However, the scraping away of the features

and the slightly simplified forms created a more powerful emotional impact than

most Impressionist paintings, and are reminiscent of Post-impressionist masters

like Vuillard and Ensor.

A SCHOLARSHIP TO PARIS

Four

years later, Munch was able to study French art at greater leisure. After the

success of his first one-man show, the Norwegian government awarded him a State

Scholarship on condition that he found an acceptable teacher. Accordingly, on

his arrival in Paris, he enrolled in the life classes of Leon Bonnat.

Munch

worked diligently at these classes, but was soon alienated by his master's

conventional academic approach. Bonnat, in turn, was impressed with his pupil's

draughtsmanship, but objected to his highly subjective use of colour. The two

men parted company after a disagreement over the precise tones of a wall in the

studio.

Despite

this setback, Munch's three-year stay in Paris was a crucial period. The death

of his father in 1889 released him from lingering family ties while, on a more

positive note, he benefited enormously from the feverish activity in the art

world. He was particularly influenced by the growing Symbolist movement, which

inspired his symbolic use of colour, his simplification of form, and even his

subject matter of the femme fatale.

Meanwhile,

a dramatic incident brought Munch international attention. In 1892, the Verein

Berliner Kunstler (Union of Berlin Artists) invited him to join their

exhibition. His paintings caused uproar and, after a week, the committee

ordered him to remove his 'daubs'. But some of the Verein's members objected

and, headed by Max Liebermann, left to form the Berlin Secession.

Meanwhile,

a dramatic incident brought Munch international attention. In 1892, the Verein

Berliner Kunstler (Union of Berlin Artists) invited him to join their

exhibition. His paintings caused uproar and, after a week, the committee

ordered him to remove his 'daubs'. But some of the Verein's members objected

and, headed by Max Liebermann, left to form the Berlin Secession.

Munch

was delighted by the furore and swiftly made arrangements to exhibit the works

in Dusseldorf and Cologne. An extensive tour of German and Scandinavian cities

followed and, through these shows, Munch earned as much from his percentage of

the entrance fees as he did from the sales of his paintings. Encouraged by this

sudden notoriety, Munch settled in Berlin and soon became attached to a new

artistic coterie, which met at Zum Schwarzen Ferkel (the Black Piglet). Among

its more vocal members were the playwright August Strindberg, and the Polish

novelist Stanislaw Przybyszewski.

Amid

the highly charged atmosphere of the group's meetings, Munch formulated plans

for his Frieze of Life. Through this ambitious scheme, he intended to assemble

a number of paintings on linked themes and display them together, in the hope

that the ensemble would create a symphonic effect. The binding theme was to be

'the poetry of life, love and death', seen through the distorting mirror of

Munch's personal experiences, and the series included many of his greatest

paintings. The Scream, The Dance of Life, Madonna (back cover), The Vampire and

Jealousy were among the works selected.

THE MEANING OF THE FRIEZE

At the

core of the Frieze was Munch's view of female sexual power. He depicted this in

three stages as awakening innocence, voracious sexuality and as an image of

death. In many cases, these three facets were combined in a single picture. The

lithograph of Madonna (back cover), for example, suggested innocence through

its title and the sketchy halo, and yet at the same time Munch chose to show

the woman at the point of orgasm and described her expression as a 'corpse's

smile'. Meanwhile, in the border, sperm wriggled like worms away from a sickly

embryo.

At the

core of the Frieze was Munch's view of female sexual power. He depicted this in

three stages as awakening innocence, voracious sexuality and as an image of

death. In many cases, these three facets were combined in a single picture. The

lithograph of Madonna (back cover), for example, suggested innocence through

its title and the sketchy halo, and yet at the same time Munch chose to show

the woman at the point of orgasm and described her expression as a 'corpse's

smile'. Meanwhile, in the border, sperm wriggled like worms away from a sickly

embryo.

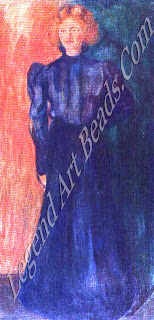

Munch's

own relations with women reflected these troubled images. Although tall and

good looking, he was wary of the opposite sex: the loss of his mother and

sister may have made him afraid of relationships with women he often portrayed

love and death together. The family history of tuberculosis and mental illness

convinced him it was unwise to marry, but he also feared marriage would

interfere with his work. His first affair, with the headstrong wife of a

medical officer, haunted him for years, while, in Berlin, he was attracted by

Przybyszewski's wife, Dagny, and portrayed her as a temptress in Jealousy. His

final, disastrous liaison with Tulla Larsen ended with her shooting off the

joint of one of his fingers.

Although

based in Germany, Munch travelled frequently, living in a succession of

boarding houses. He was not a healthy man and his nomadic lifestyle must have

mentally and physically exhausted him. Money was also a problem and, on one

occasion, a patron rescued Munch after he had been evicted from his room and

was forced to wander the streets of Berlin for three days without food.

Nevertheless,

these were productive years. On a visit to Paris Munch met Paul Gauguin and his

followers and, at Bing's Art Nouveau gallery, he saw the influential exhibition

of Japanese woodcuts. Also in Paris, he developed his interest in new printing

techniques, under the supervision of the renowned graphic artist, Auguste Clot.

IMPORTANT COMMISSIONS

Munch's

major commissions at the turn of the century came from his friend, Dr Linde. In

addition to a superb portrait of the doctor's four sons, the artist completed a

folio of prints for him and drew up plans for a frieze to decorate his nursery.

The latter was never executed; however, as Linde eventually decided that

Munch's work might not be suitable for his children's room.

In

1906-7, he gained several other important commissions from Max Reinhardt, to

provide a frieze for his new Kammerspiele theatre and design sets for lbsen's

Ghosts and Hedda Gabler. While he was working on these pictures, Munch lived in

the theatre, painting by day and drinking by night. He kept himself remote from

other people, causing a colleague to admit that 'He remained both a stranger

and a puzzle to us'.

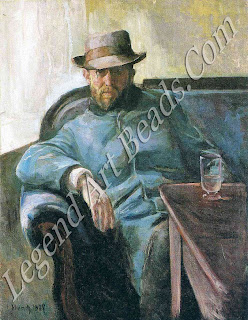

The

shooting incident with Tulla Larsen, excessive drinking and exhaustion began to

take their toll, and Munch became obsessed with feelings of persecution which

were not helped by the abusive criticism of his work by his countrymen.

Finally, in 1908, after a three-day drinking spree, he suffered a nervous

breakdown and was admitted to Daniel Jacobson's clinic in Copenhagen. There, he

recuperated for eight months, receiving various forms of therapy.

The

shooting incident with Tulla Larsen, excessive drinking and exhaustion began to

take their toll, and Munch became obsessed with feelings of persecution which

were not helped by the abusive criticism of his work by his countrymen.

Finally, in 1908, after a three-day drinking spree, he suffered a nervous

breakdown and was admitted to Daniel Jacobson's clinic in Copenhagen. There, he

recuperated for eight months, receiving various forms of therapy.

Munch

had always been aware of the danger inherent in allowing his creativity to feed

off his neuroses, but chose to ignore it. 'I would not cast off my illness' he

had written 'for there is much in my art that I owe to it.' Now, however, he

dedicated himself to recovery. In doing so, he made a conscious decision to

abandon the obsessive, neurotic imagery of the past. Henceforward, he would

depict the things he saw around him, rather than his emotions.

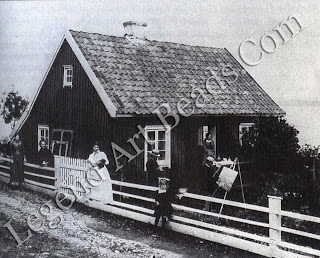

In

addition, Munch resolved to put an end to his wandering.. Hitherto, he had

spent only his summers in Norway, at Asgardstrand, but now he returned there

permanently, settling at first in the coastal town of Kragero.

Ironically,

the ending of Munch's most creative period coincided with greater official

recognition. In 1908, he was made a Knight of the Order of St Olav and, in 1911,

he won the prestigious competition for decorating the University Assembly Hall.

Here, he installed a new Frieze of Life, although this time he chose to portray

universal forces The Sun, History, Alma Mater rather than the inner workings of

the soul.

FINAL PROJECTS

FINAL PROJECTS

Munch

aimed to produce further public murals. In particular, he cherished the idea of

designing a frieze on the theme of working men and industry. Preliminary

sketches were displayed in the dining room of the Freia Chocolate Factory in

1922 but, sadly, the project never materialized. Munch also offered his

services for the decoration of the new City Hall in Oslo, but the building work

was delayed until 1933, by which time the artist had an eye complaint and could

no longer paint.

Munch's

last years were spent in isolation at his estate in Ekely. Here, he lived a Spartan

life, surrounded by the paintings which he called his 'children'. Despite this

term of affection, he treated them badly, littering his prints on the floor and

hanging his paintings out on the apple trees to dry. With the rise of the

Nazis, Munch's art was branded as degenerate and his pictures sold off from

German museums. Then, in December 1943, he contracted a fatal dose of

bronchitis after a bomb blew out the windows of his house. He died on 23

January 1944. In his will, he generously bequeathed his entire collection of

prints and paintings some 20,000 in all to the city of Oslo.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

By this

time, he had already decided on art as a career. His studies in engineering at

the Technical College had lasted less than a year and, in 1881, he entered the

State School of Art and Crafts. His initial supervisor there was Julius

Middelthun, but the dominant influence on his early development was the

naturalist painter, Christian Krohg. In 1882, along with six other artists,

Munch rented a studio where Krohg provided informal instruction.

By this

time, he had already decided on art as a career. His studies in engineering at

the Technical College had lasted less than a year and, in 1881, he entered the

State School of Art and Crafts. His initial supervisor there was Julius

Middelthun, but the dominant influence on his early development was the

naturalist painter, Christian Krohg. In 1882, along with six other artists,

Munch rented a studio where Krohg provided informal instruction.  Meanwhile,

a dramatic incident brought Munch international attention. In 1892, the Verein

Berliner Kunstler (Union of Berlin Artists) invited him to join their

exhibition. His paintings caused uproar and, after a week, the committee

ordered him to remove his 'daubs'. But some of the Verein's members objected

and, headed by Max Liebermann, left to form the Berlin Secession.

Meanwhile,

a dramatic incident brought Munch international attention. In 1892, the Verein

Berliner Kunstler (Union of Berlin Artists) invited him to join their

exhibition. His paintings caused uproar and, after a week, the committee

ordered him to remove his 'daubs'. But some of the Verein's members objected

and, headed by Max Liebermann, left to form the Berlin Secession.  At the

core of the Frieze was Munch's view of female sexual power. He depicted this in

three stages as awakening innocence, voracious sexuality and as an image of

death. In many cases, these three facets were combined in a single picture. The

lithograph of Madonna (back cover), for example, suggested innocence through

its title and the sketchy halo, and yet at the same time Munch chose to show

the woman at the point of orgasm and described her expression as a 'corpse's

smile'. Meanwhile, in the border, sperm wriggled like worms away from a sickly

embryo.

At the

core of the Frieze was Munch's view of female sexual power. He depicted this in

three stages as awakening innocence, voracious sexuality and as an image of

death. In many cases, these three facets were combined in a single picture. The

lithograph of Madonna (back cover), for example, suggested innocence through

its title and the sketchy halo, and yet at the same time Munch chose to show

the woman at the point of orgasm and described her expression as a 'corpse's

smile'. Meanwhile, in the border, sperm wriggled like worms away from a sickly

embryo.  The

shooting incident with Tulla Larsen, excessive drinking and exhaustion began to

take their toll, and Munch became obsessed with feelings of persecution which

were not helped by the abusive criticism of his work by his countrymen.

Finally, in 1908, after a three-day drinking spree, he suffered a nervous

breakdown and was admitted to Daniel Jacobson's clinic in Copenhagen. There, he

recuperated for eight months, receiving various forms of therapy.

The

shooting incident with Tulla Larsen, excessive drinking and exhaustion began to

take their toll, and Munch became obsessed with feelings of persecution which

were not helped by the abusive criticism of his work by his countrymen.

Finally, in 1908, after a three-day drinking spree, he suffered a nervous

breakdown and was admitted to Daniel Jacobson's clinic in Copenhagen. There, he

recuperated for eight months, receiving various forms of therapy.

0 Response to "The Great Artist Edvard Munch"

Post a Comment