Born in

1882 in Nyack, near New York City, Edward Hopper is the greatest painter of

modern American life yet to emerge. He studied painting in New York with Robert

Henri, founder of the Ashcan school. On leaving college, he became a commercial

artist, only giving up this career at the age of 42 to become a full-time

artist. His interest in the effects of light was inspired by the

Impressionists, whose work Ix saw in Paris.

Hopper

found his very distinctive style in the 1920s and hardly changed it at all from

then on. Although he lived through the heyday of abstraction, Hopper remained

committed to the tradition of representational painting. Despite his late

start, America was quick to heap honours upon him. But he remained a very

private man, leading a life dedicated to painting with his wife, a fellow artist.

Hopper died in 1967, aged 84.

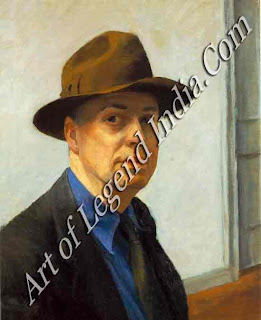

A tall,

laconic American, Edward Hopper liked to think of himself as a down-to-earth,

self-made man. He cherished his personal privacy, preferring silence to idle

chatter and artistic pretension.

Edward

Hopper grew up in middle-class small-town America. He was born on 22 July 1882

in Nyack, on the Hudson River just above New York City, the son of a

shopkeeper. He later described his father as 'an incipient intellectual who

never quite made it'. Edward was a solitary, bookish boy, who stood apart from

other children because of his abnormal height he suddenly grew to six feet at

the age of 12. The Hoppers' home overlooked the Hudson, and Eddie, as he was

then called, developed an early enthusiasm for boats, building his own cat-boat

at 15 with wood and tools supplied by his father.

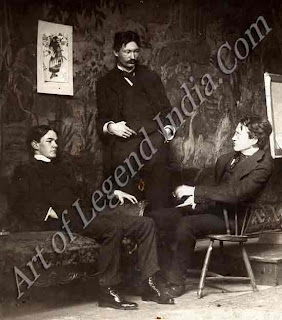

Encouraged

by his mother, Hopper soon began to demonstrate a precocious talent for drawing

and, at the age of 17, he entered the Correspondence School of Illustrating in

New York. The following year he transferred to the New York School of Art,

studying first illustration and then painting. He found himself among an

exceptionally gifted generation of students, including famous names of the

future such as George Bellows and Rockwell Kent. His most t inspiring teacher

was Robert Henri, who fostered Y. in him a taste for subjects from everyday

urban life in the USA, as well as a respect for the great realist 3 masters of

the past; Velazquez, Goya, Daumier, Manet and Degas.

In

1906-7, with the money he saved from a brief, unsatisfying stint of work as an

illustrator with an advertising agency, and some help from his parents, Hopper

was able to realize his ambition of visiting the art capital of the world,

Paris. He stayed there for a few months and had an utterly un-bohemian time. His

parents made arrangements through the Baptist Church for him to stay with a

suitable bourgeois family, and he seems to have taken no interest in

avant-garde artists or their work. Instead, he came under the spell of

Impressionism, and developed an interest in capturing effects of light that was

to stay with him for his whole career as a painter. He was in Paris again in

1909 and 1910, after which he never again returned to Europe.

1882 born in Nyack, on the Hudson

River

1900-6 attends New York School

of Art, studying under Henri

1906-10 makes painting trips to

Paris

1913 sells painting in Armory

Show

1924 marries Jo Verstille Nivison;

abandons commercial work

1932 shows work in Whitney

Museum exhibition

1934 builds studio-house at Cape

Cod

1950/64 retrospective

exhibitions

1967 dies at studio in New

York

Back in

America, Hopper began to exhibit fairly regularly in New York, not at the

conservative National Academy of Design, which rejected his work, but at the

small anti-academic exhibitions organized by Robert Henri and other former

pupils at the MacDowell Club. But no critics or collectors took any serious

interest in him, and actually making a living from painting seemed out of the

question. Indeed, it is a measure of the doggedness that was part of Hopper's

character that he continued with art at all, only becoming a full-time painter

in 1924, at the age of 42.

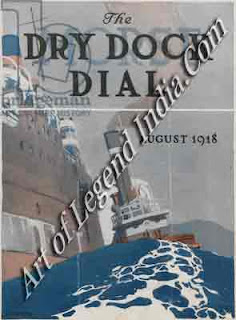

Until

that date, Hopper reluctantly supported himself by commercial design and fairly

routine illustrative jobs, working three days a week for advertising agencies

and strictly non-artistic journals such as The Farmer's Wife, The Country

Gentleman and System, the Magazine of Business. On occasion, he would eke out

his income by giving art lessons to children back home in Nyack, which he

disliked even more. He managed to sell a painting for $250 at the famous Armory

Show in 1913, and in 1918 won a prize of S300 from the US Shipping Board for a

propaganda poster entitled smash the Hun, but consistent success eluded him.

In

1913, Hopper took the studio at Washington Square North in New York City that

he occupied for the rest of his life, renting extra working and living space as

his finances allowed, yet never altering the bare, Spartan look of the place.

The habit of thrift instilled in him by his upbringing and deepened by the lean

early years of his career seems never to have left him, even after he became

quite wealthy. He would eat in the shabbiest restaurants and diners wear

clothes until they were threadbare and buy second-hand cars that he drove until

they gave up the ghost.

Hopper

had his first one-man exhibition in 1920, showing 16 oils painted in Paris and

during summer trips to the bleak, rocky Monhegan Island, Maine, about 300 miles

north-east of New York. Not a single work was sold, but the venue was an

auspicious one Whitney Studio Club. Founded by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney,

this was the forerunner of the famous Whitney Museum of American Art. The

museum was opened in 1931 and the same year bought Early Sunday Morning for its

permanent collection. Hopper was to be closely associated with the Whitney

throughout his life, showing new works in almost all the contemporary

exhibitions that were held there from 1932 onwards.

Unexpectedly,

Hopper made his long-awaited breakthrough in watercolour rather than in oils.

He only began using watercolour seriously in 1923, during a summer sketching

trip to Gloucester, Massachusetts. Later that year, the Brooklyn Museum

accepted six of the views he painted there for an exhibition; they were

favourably noticed by reviewers and the museum bought one of them for $100.

After a further successful watercolours' exhibition in 1924 at the gallery of

Frank K. M. Rehn, who became his dealer for the rest of his life, Hopper at

last felt sure enough of making a living to devote himself exclusively to

painting.

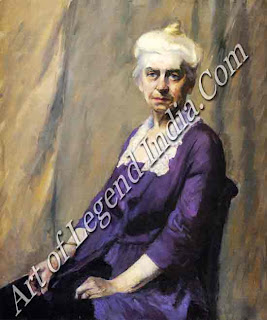

On 9

July 1924, he married Josephine (Jo) Verstille Nivison at the Baptist 'Eglise

Evangelique' in New York. They had been students together under Robert Henri

and had met by chance on visits to Maine and Massachusetts. Jo had trained as

an actress before she took up art, and was as talkative as Hopper was taciturn.

She was tiny, had a strong character, hated domestic duties and loved cats. Jo

was also possessive, and insisted that Hopper gave up drawing from the nude

model unless she modelled for him. As a result, many of the women in his

paintings, and all the nudes, are portraits of Jo.

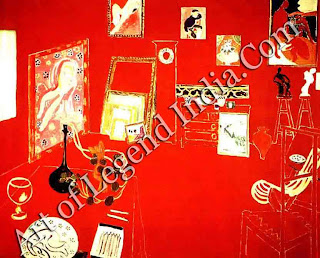

It was

in the mid-1920s that Hopper forged the very distinctive style that we

associate with his name, and his work changed little from then on. The growing

reputation he enjoyed was reflected in the increasingly prestigious exhibitions

devoted to him: a one-man show at the Frank K. M. Rehn Gallery in 1929,

retrospectives at the Museum of Modern Art in 1933 and the Whitney Museum in 1950,

and a major retrospective at the Whitney in 1964 which toured afterwards to the

Art Institute of Chicago, the Detroit Institute of Arts and the City Art Museum

of St Louis.

Hopper

also accumulated prizes and honours. In 1932, the National Academy of Design

elected him an associate member, which he was pleased to refuse as the Academy

had refused him during his years of struggle and obscurity. The Pennsylvania

Academy of the Fine Arts awarded him the Temple Gold Medal in 1935, the first

of many such awards from American academies and museums. He won a series of

prizes at the Institute of Chicago, which in 1950 conferred upon him the

honorary degree of Doctor of Fine Arts; he was one of the four artists chosen

to represent the USA at the Venice Biennale of 1952; and in 1955, the American

Academy of Arts and Letters presented him with a Gold Medal for Painting.

By

1934, Hopper was able to build a studio-home away from it all at South Truro on

Cape Cod, where he and Jo stayed for part of almost every summer for the rest

of their lives. Success also enabled him to indulge his liking for travel it is

no accident that so many of Hopper's paintings depict hotels, motels and life

on the road and in 1941, he and Jo made a three-month grand tour by car across

the country to the West Coast and back. In 1943, there was a petrol shortage

that prevented them from driving anywhere, even up to Cape Cod, so they made a

train trip to Mexico instead, the first of a number of holidays they spent

there.

Hopper's

pleasures in life were never extravagant. He enjoyed the theatre, the cinema

and books. He was quite exceptionally well read and not only in English

literature: he was able to quote fluently from Goethe and the French Symbolist

poets in the original. He was especially fond of Symbolist verse, first

discovering it as a student and as late as 1951, giving Jo a volume of Rimbaud

for Christmas with an affectionate inscription in French. Indeed, there is a

strange melancholy about many of his paintings that the Symbolists, and most of

all Baudelaire, would surely have recognized.

In

spite of his rather sophisticated literary tastes, Hopper cultivated the public

persona of the down-to-earth self-made man who cared little for fancy ideas.

This may well have been a ploy designed to exempt him from seriously discussing

his own work. When interviewed, he usually refused to acknowledge any

intellectual or personal content in his pictures and claimed to be merely

working within the American Realist tradition, painting neither more nor less

than what he happened to see around him.

Hopper

was also wholly committed to representational art and watched the rise of

Abstract Expressionist painting in the 1950s and 60s with dismay. He was a

member of the group of representational painters who, in 1953, launched the

journal Reality as a mouthpiece for their point of view, serving for a time on

its editorial committee. In 1960, he and his Reality colleagues made a

concerted protest to the Whitney Museum and the Museum of Modern Art against

the 'gobbledygook influences' of abstract art in their collections. Curiously

enough, the abstract painters expressed nothing but admiration for Hopper, in

whose work they saw an interest in pure form and a play of space against

flatness that anticipated their own experiments.

In the

words of one friend, Hopper gave off 'a sense of geological presence that

redefined inertia'. He was slow and laconic in his work as a painter,

completing only two or three oils a year, and even more so in his social

manner. He regarded conversation as mere chatter, not worth the physical effort

required to produce it. If he had nothing to say, which was generally the case,

he would remain silent. The idea of filling in awkward moments with small talk

would have seemed as absurd to him as filling in the empty wall-surfaces in his

paintings with pretty decorations.

Critics

inferred from the lonely mood that pervades so many of Hopper's paintings that

he must himself have suffered loneliness. He certainly spent much of his time

alone, whether painting, reading or deep in thought, but it was by choice. He

cherished solitude and had little love of company except that of his wife. The

unsmiling suspicious look on his face in photographs makes us feel that we have

intruded into a very private life. It also, somehow, makes us feel small.

lopper's withdrawal from the world was rooted in a profound pessimism; the same

friend wrote that 'he views his fellow man as a flimsy and often trivial

construct'.

The

word that invariably crops up in the recollections of those who knew Hopper is

'puritan'. He did come from an Anglo-Saxon Protestant background: his parents

were of Dutch and English origins, and both devout Baptists. More

significantly, he always conveyed the impression of strong feelings kept

tightly under control, despising any kind of self-indulgent emotionalism or ostentation

as though to give so much away made a person ridiculous.

In

1965, Hopper painted his last picture, Two Comedians, showing a couple

reminiscent of himself and Jo taking their final bow before leaving the stage.

He died in his studio at 3 Washington Square North on 15 May 1967, aged 84. Jo

died the following year and bequeathed the entire artistic estate, including

over 2,000 of Hopper's paintings, watercolours, drawings and prints, to the

Whitney Museum of American Art.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "American Great Artist Edward Hopper Life"

Post a Comment