American Great Artist Edward Hopper - The Ashcan School

Posted by

Art Of Legend India [dot] Com

On

2:44 AM

Labelled

as vulgar by the critics, the Ashcan school of painters was a flourishing and

original group whose inspiration was drawn from New York street scenes and the

seamier side of city life.

In the

early years of the 20th century, American painting finally emerged from the

shadow of European art and began to assert its own identity. Leading these

advances was a group of social realist painters who came to be known as the

Ashcan school.

The leader

of this influential group was the painter and teacher Robert Henri. Born Robert

Henry Cozad, Henri changed his name after his family was forced to flee

Cincinnati following his father's involvement in a shooting incident. Henri's

own work came firmly within the European orbit, his portraits bearing a close

resemblance to those of Manet. However, Henri's true importance lay in the

direction that his teaching gave to the realist movement. One commentator

described him as a 'silver-tongued Pied Piper'.

Henri

travelled to Europe on several occasions in the 1880s and 1890s. In 1888, he

was in Paris, studying under the academic painter, Adolphe Bouguereau and, in

1895, he visited Holland with William Glackens. Like Henri, Glackens' link with

the Ashcan school was tempered by his obvious fondness for European art and his

canvases reveal a particular liking for the work of Renoir.

On his

return to the States, Henri settled in Philadelphia and, from 1892-95, he

taught at the Women's School of Design. His own studio became a popular meeting

place for artists and it was during this period that the future members of the

Ashcan school first came together. Many of these artists worked initially as

illustrators on newspapers. George Luks, Everett Shinn, John Sloan and William

Glackens all began their careers this way, before Henri persuaded them to take

up painting and translate the immediacy and topicality of their journalistic

work into a vigorous new form of

American art.

Henri

preached a positive brand of liberal humanism, stressing his belief in

progress, justice and the common bonds of humanity. He called upon artists to

portray modern American life, not with the superficial prettiness that was

popular in the academies, but with the social awareness of a Goya or a Daumier.

'Be willing to paint a picture that does not look like a picture,' was his

maxim.

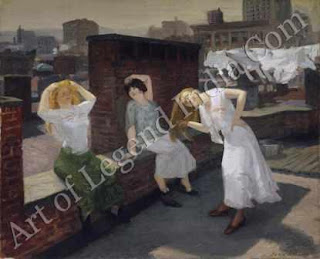

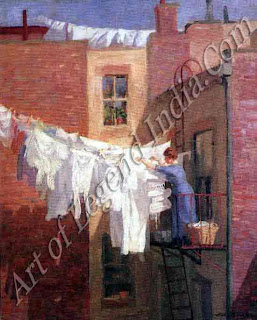

Towards

the end of the 19th century, the Philadelphia realist painters migrated to New

York, where the overcrowded suburbs gave an increasingly urban slant to their

pictures. Cinema audiences and street scenes in the slums were typical

subjects, while bars like McSorleys provided a virtual replica of night life in

the Latin Quarter of Paris.

In New

York, however, they also came up against the opposition of the National Academy

of Design. This imposing body had been founded in 1826 and was, in its early

days, an important sponsor of native American art. By the time that

Impressionism and Realism made their appearance, however, it had become

extremely conservative. In 1907, Luks, Glackens and Shinn were among the

artists who had their works rejected for its annual show. Henri, who was one of

the selection committee on this occasion, withdrew his own entries in protest

and set about organizing an independent exhibition.

The

result was a show by 'the Eight', which took place in February 1908 at the

Macbeth Galleries, where Henri had previously held a one-man exhibition. 'The

Eight' were not a cohesive group and this was to be the only time they

exhibited together. Nonetheless, the vitality and modernity of the paintings on

display made this a landmark of American art and a rallying point for

supporters of the avant-garde. The critics, however, were 'less enthusiastic.

'Vulgarity smites one in the face at this exhibition,' complained one

correspondent, and the feeling that certain artists were glorying in the noise

and the squalor of city E life earned them the tag of 'the Ashcan school'.

Only

five of 'the Eight' were attached to the Ashcan group Henri, Luks, Shinn, Sloan

and Glackens. Of these, probably the artist who best typified its spirit was

John Sloan, who is sometimes known as 'the American Hogarth'. Sloan was a

committed socialist and was later a co-founder of The Masses, a political

journal to which Henri, Luks and Bellows all contributed E illustrations. His

diaries show how closely he based his paintings on the scenes and incidents

that he witnessed in the city streets. Hopper was a fervent admirer of his work

and in an article of 1927, entitled 'John Sloan and the Philadelphians', he

singled out the former's Night Windows for particular praise. Then, a year

later, he produced his own version, using the same voyeuristic theme of a woman

glimpsed through an open window.

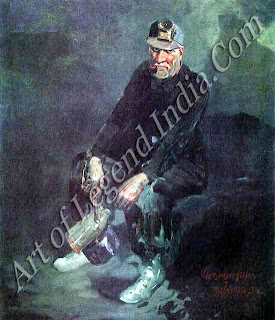

Where

Sloan viewed the life of the poor with sympathy and as a forum for political

struggle, George Luks found the slums a source of vigour, excitement and

modernity. Luks, himself, was a flamboyant and brash character and sought to

project this image in a series of extravagant fabrications about his early

career. His claims to have earned a living as a coal miner and as a fighter

called 'Chicago Whitey' and 'the Harlem Spider' are probably apocryphal, but it

is true that he was almost killed by a firing squad when, as a reporter, he was

sent to cover the Spanish-American war in Cuba. Luks' painting shows a similar

sense of adventure, with a loose handling and brushwork that reveals a clear

debt to Frans Hals. His style is best exemplified by his depiction of

wrestlers.

RED-BLOODED ART

Fighting

scenes were also popular with George Bellows, another painter associated with

the Ashcan school. Bellows did not exhibit with 'the Eight', but his art

contained many of the aggressively American qualities that typified the spirit

of the group. He never went abroad and thus found it easier than his colleagues

to ward off European influences. In addition, he was a keen sportsman and

seemed to symbolize the Ashcan ideal of the all-American, red-blooded male.

In his

youth, he played semi-pro baseball at Columbus, Ohio, and was invited to join the

Cincinnati Reds. Bellows chose art as a career instead, although his continuing

interest in sport is evident from his paintings. He depicted baseball, polo and

tennis scenes, but is most famous for six stirring pictures of boxing matches.

Prize-fighting

was illegal in New York at this time, and bouts were staged in private athletic

clubs, with both the spectators and the fighters taking out temporary

membership. Bellows' studio was almost opposite Sharkey's Club in Broadway, and

this venue provided a rich source of material for him. His brutal ringside

views are remarkable both for the blurred, mask-like faces of the audience and

for their sheer presence which, in the absence of photographic reporting, must

have seemed all the more striking. Bellows emphasised his interest in the

physicality of such scenes. 'Who cares what a prize-fighter looks like?' he

commented, 'its muscles that count.

Bellows

had considerable conventional success, becoming the youngest Associate of the

National Academy in 1909. For his colleagues, however, it was more important to

set an alternative standard to these academic plaudits. In 1910, Henri

organized the Exhibition of Independent Artists; it was the first American show

to have no jury and no prizes, and where each painter paid for the space he

used.

Three

years later, modern art made its decisive breakthrough in America at the Armory

Show. Ironically, the impact of the European contributions at this exhibition

made the work of the urban realists seem old-fashioned and heralded their

decline. It required the emergence of Hopper, Henri's pupil, to underline the

true achievements of the Ashcan school.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "American Great Artist Edward Hopper - The Ashcan School"

Post a Comment