William

Hogarth

1697-1764

One of

Britain's most gifted and influential artists, Hogarth achieved fame both as a

painter and as an engraver. His pictures were widely circulated in printed

form, and were enormously popular. Their subject matter was drawn from the

London the artist observed around him, and his early experience of his father's

imprisonment for debt gave him an enduring interest in the seamier sides of

life in the city.

Hogarth

was working at a time when British art was largely dominated by foreign

artists, and he did much to promote the position of native British artists. He

also brought fresh vigour to conventional portraiture, and helped introduce

theatre pictures and conversation pieces to British art. But it is as the

inventor of that particularly British genre the modern moral narrative that he

is best remembered today.

The William Hogarth’s life

A Fervent Patriot

Pugnacious

and patriotic when it came to recognizing the worth of English art, Hogarth's

successful career was a never ending battle against 'connoisseurs',

printsellers and publishing pirates.

Pugnacious

and patriotic when it came to recognizing the worth of English art, Hogarth's

successful career was a never ending battle against 'connoisseurs',

printsellers and publishing pirates.

William Hogarth was born on 10 November 1697, in Smithfield.

His father, Richard Hogarth, was a failed schoolmaster and writer who tried to

recoup his fortunes by keeping a superior kind of coffee house for the learned,

a place where 'the master of the House, in the absence of others, is always

ready to entertain gentlemen in the Latin tongue'. This venture failed, and by

the time William was 12, the family was living in The Fleet, a debtors' prison.

His mother was making what she could by selling an ointment 'which, in the very

moment of application, cures the gripes in young children and prevents fits'.

Unfortunately two of her own children, William's brothers, died during this time.

In

September 1712, Hogarth's father was released from the Fleet, and the family

took up residence in Long Lane. And, just over a year later, with the help of

his uncle, Edmund Hogarth, a prosperous victualler at London Bridge, William e,

was apprenticed for seven years to Ellis Gamble silver plate engraver.

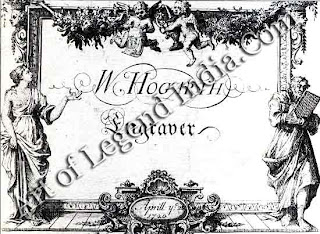

In the

spring of 1720, when his apprenticeship still had nearly one year to run,

Hogarth set up on his own. It was a bold gesture, but perhaps a necessary one.

His father was dead worn out, he insisted, by 'the cruel treatment he met with

from booksellers and printers'. Uncle Edmund was also dead and had turned

against Hogarth's mother and cut her out of his will, so it may well have been

essential for William to cut short his apprenticeship and become the

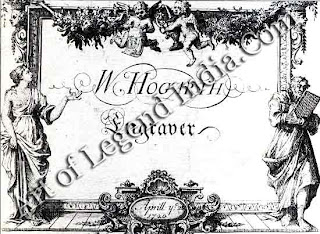

breadwinner of the family. This he did by issuing a shop card and opening a

business at his mother's house in Long Lane. On the card were printed the words

W. Hogarth, Engraver' flanked by two figures symbolizing Art and History,

making it clear that the young Hogarth would no longer be a mere craftsman but

was determined to be an artist and a history artist at that.

Convinced

as he was that the status of English painting should be elevated, Hogarth still

found that when he started learning to paint formally in 1720, he had to go to

an academy in St: Martin’s Lane run by two painters of foreign extraction, John

Vanderbank and Louis Cheron and pay a fee of two guineas. Three years later,

however, the academy closed, but a free academy was opened by Sir John

Thornhill at his house in Covent Garden. Hogarth was one of Thomhill's first

pupils, being a great admirer of the history painter who was the first English born

painter to receive a knighthood.

Key Dates

1697 born in London

1714 apprenticed to the engraver

Ellis Gamble

1720 sets up own engraving

business

1729 marries Jane Thornhill.

Starts to paint conversation pieces and portraits

1731 paints A Hanoi's

Progress

1733 sets up shop as a print seller

1734 paints A Rake's Progress

1735 founds St Martin's Line

Academy

1739 is a founding governor

of the Foundling Hospital

1743 paints Marriage a la

Mode

1753 Analysis of Beauty

published

1754 finishes the Election

series

1764 dies in London

INFORMAL TRAINING

Later,

in 1735, when Hogarth's reputation was well established, he founded a 'new' St

Martin's Lane Academy, a relatively informal school for practising artists as

well as younger students, organized on democratic lines. His attitude to

academies or schools of art was to remain ambivalent. While appreciating the

value of some kind of informal training, he publicly and frequently attacked

the formal, rigidly structured schools run on the lines of the French Academy.

He claimed they stifled initiative, encouraged adherence to outworn rules and

turned out too many students hoping for a career in Fine Art whose ambitions

were bound to be dashed in a society which generally cared little for native

artists.

Later,

in 1735, when Hogarth's reputation was well established, he founded a 'new' St

Martin's Lane Academy, a relatively informal school for practising artists as

well as younger students, organized on democratic lines. His attitude to

academies or schools of art was to remain ambivalent. While appreciating the

value of some kind of informal training, he publicly and frequently attacked

the formal, rigidly structured schools run on the lines of the French Academy.

He claimed they stifled initiative, encouraged adherence to outworn rules and

turned out too many students hoping for a career in Fine Art whose ambitions

were bound to be dashed in a society which generally cared little for native

artists.

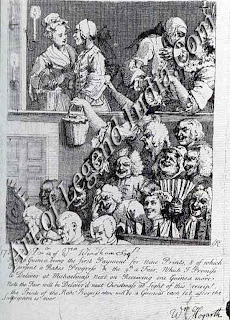

In the

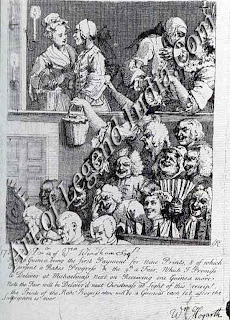

early 1720s Hogarth did some engraved illustrations to literary works, but one

of his first independent engravings was a satire, The Taste of the Town, also

known as Masquerades and Operas. In it Hogarth ridiculed the fashionable taste

for Italian operas and Italian singers to the detriment of the works of British

playwrights and authors. The Taste, Hogarth's first satire, announced themes

which were to run through the whole of his work his patriotism, his opposition

to what he considered as mindless adulation for French and Italian art and

artists, his references to actual contemporary events and people and the

overwhelmingly topical thrust of his art.

A LOVER OF THEATRE

Around

this time, too, Hogarth started to produce oil paintings. Although this was a

medium in which he had had no formal training, by 1728 he had gained enough

mastery to paint a number of versions of John Gay's Beggar's Opera, which was

itself in part a satire on Italian opera. Hogarth was fascinated by theatre and

shows of all kinds, and in these compositions showed the action on stage.

'Subjects I considered as Writers do,' he wrote, 'my picture was my stage and

men and women my actors who were by means of certain actions and expressions to

exhibit a dumb show.'

In

about 1729 the year he eloped with Jane, Thornhill's daughter Hogarth started

to paint group portraits or 'conversation pieces' for a largely aristocratic

clientele. As an ambitious man it may have appeared that he was establishing

himself as a painter of portraits in the conventional sense, the only branch of

art where a native artist could expect to make a respectable income. But he was

not temperamentally suited to the routine drudgery of 'face painting' alone and

found that painting conversation pieces 'was not sufficiently paid to do

everything my family required'. Hogarth had a very stable family life with his

wife, although they appear to have had no children.

SUCCESSFUL ENGRAVINGS

Hogarth

and his wife moved in with Sir James Thornhill in 1731, and the same year

Hogarth painted the series A Harlot's Progress. Realizing that the sale of the

paintings alone would not bring in much money he hit on the idea of engraving

his works and selling them widely by subscription, already a familiar and

indeed standard practice in the publication of literary works. A Harlot's

Progress was issued the following year and was an immediate success. The

subscription of the engravings, which he did himself, though he was to employ

other engravers for some of his later engraved series, brought him £1200. This

can be compared with the E700 which Henry Fielding got for his novel Tom Jones

and the E1500 which Samuel Johnson got for his famous Dictionary. The success

of Hogarth's Harlot can be gauged by the fact that two weeks after the

publication of the prints a pamphlet appeared setting forth the story in verse

which went through four editions in 17 days and Fielding's play, The Covent

Garden Tragedy, of 1732, was in part inspired by the Harlot. Hogarth's aim was

for his narrative series, such as the Harlot and later A Rake's Progress and

Marriage a la Mode, to be seen not just as popular prints, but as modern

'History' paintings, to be judged by the same criteria as the High Art of the

Italian Renaissance masters. When in the autumn of 1733, Hogarth set up shop as

a print seller in his own right, he hung a gilded head of Sir Anthony Van Dyck

over his shop door to show he was the successor to the great foreign painters

of the past. The shop was called 'The Golden Head'.

While

working on his second major series, The Rake's Progress in 1734, Hogarth also

tried his hand at religious decorative painting, executing two murals for the

staircase of St Bartholomew's Hospital, the Pool of Bethesda and The Good

Samaritan. These he did free of charge, partly because it was for a charitable

purpose in an area of London he knew well and partly because there was a danger

of the commission going to an Italian painter, Jacopo Amigoni. Hogarth had

wanted to succeed in this more traditional form of High Art, but although he

later painted some more religious pictures, such as an altarpiece for St Mary

Redcliffe, Bristol, Hogarth was ill-at-ease in this kind of work.

While

working on his second major series, The Rake's Progress in 1734, Hogarth also

tried his hand at religious decorative painting, executing two murals for the

staircase of St Bartholomew's Hospital, the Pool of Bethesda and The Good

Samaritan. These he did free of charge, partly because it was for a charitable

purpose in an area of London he knew well and partly because there was a danger

of the commission going to an Italian painter, Jacopo Amigoni. Hogarth had

wanted to succeed in this more traditional form of High Art, but although he

later painted some more religious pictures, such as an altarpiece for St Mary

Redcliffe, Bristol, Hogarth was ill-at-ease in this kind of work.

PIRATE PUBLISHERS

Hogarth's

profits from The Harlot had been curtailed by the pirating of his prints by

unscrupulous publishers and printsellers. Remembering his father's experiences

at the hands of these profiteers, Hogarth campaigned for an Engravers'

Copyright Act which was passed through Parliament in 1735. He delayed the

engravings of The Rake until the Act was on the Statute Book, thus ensuring

that, as he wrote 'I could secure my Property to myself'. This Act was to

benefit many future artists and engravers and shows how Hogarth, with his

pugnacious character, was always determined to transform ideas into practical

reality.

By the

late 1730s Hogarth's reputation was well established, as was his attitude to

the world and his art. His face stands out in The Painter and his Pug tough,

challenging and matter of fact lie wanted to lead thought rather than tamely to

work to commission simply as a craftsman. Although constantly attacking the

connoisseurs and gentlemen theorists, his battling nature led him to fight on their

own ground. He published his own art theory, The Analysis of Beauty, in 1753,

which argued that beauty resided in the serpentine line. This line of Beauty

and Grace had already been shown in the same self-portrait, which with its

inclusion of books labelled 'Shakespeare', 'Swift' and 'Milton', amounted to a

kind of artistic manifesto.

HIGH SOCIETY SATIRE

Hogarth's

third major series, Marriage a la Mode, was completed in 1743. This satire on a

marriage of convenience doomed to failure and tragedy focused on higher society

than The Harlot and The Rake, though the story of human greed and fecklessness

set within the teeming variety of London's people is just as moral. Hogarth

employed well-known French engravers to produce the plates and gave to the

compositions a greater refinement and complexity of meaning and allusion than

his work of the 1730s. But the series was less successful than the earlier

ones, perhaps because it attacked the very people who were likely to be

subscribers and patrons.

In this

same year Hogarth suffered a major setback when he decided to sell his pictures

by auction to show that they were in as much demand as the imported 'Old

Masters'. The result of the first sale, and of a second held six years later,

was so disastrous that he tore down the gilded head of Van Dyck from above his

shop door.

In this

same year Hogarth suffered a major setback when he decided to sell his pictures

by auction to show that they were in as much demand as the imported 'Old

Masters'. The result of the first sale, and of a second held six years later,

was so disastrous that he tore down the gilded head of Van Dyck from above his

shop door.

Hogarth's

assertiveness and bitterness intensified as he grew older. In 1759 he painted a

grand style subject from the classical mythology, Sigismunda, because he was

furious that a so-called Correggio of the same subject had been sold for the

large sum of £404.5s. He considered it to be the work of an inferior artist, as

it was, but his own Sigismunda was rejected by Sir Richard Grosvenor, his

potential client, and Hogarth gave directions before his death that it should

not be sold for less than £500. In the early 1760s a brief, late foray into political

satire together with a hostile engraved portrait of John Wilkes and a public

argument with Charles Churchill, both former friends, showed that his fighting

spirit was with him till the end. He died in 1764, still battling to get his

Sigismunda engraved, still hostile to the fashionable and unquestionable 'Old

Masters', still attacking the picture dealers whose interest, he wrote with all

the resentment toward them he had felt through-out his life, was `to depreciate

every English work, as hurtful to their trade'.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Pugnacious

and patriotic when it came to recognizing the worth of English art, Hogarth's

successful career was a never ending battle against 'connoisseurs',

printsellers and publishing pirates.

Pugnacious

and patriotic when it came to recognizing the worth of English art, Hogarth's

successful career was a never ending battle against 'connoisseurs',

printsellers and publishing pirates.  Later,

in 1735, when Hogarth's reputation was well established, he founded a 'new' St

Martin's Lane Academy, a relatively informal school for practising artists as

well as younger students, organized on democratic lines. His attitude to

academies or schools of art was to remain ambivalent. While appreciating the

value of some kind of informal training, he publicly and frequently attacked

the formal, rigidly structured schools run on the lines of the French Academy.

He claimed they stifled initiative, encouraged adherence to outworn rules and

turned out too many students hoping for a career in Fine Art whose ambitions

were bound to be dashed in a society which generally cared little for native

artists.

Later,

in 1735, when Hogarth's reputation was well established, he founded a 'new' St

Martin's Lane Academy, a relatively informal school for practising artists as

well as younger students, organized on democratic lines. His attitude to

academies or schools of art was to remain ambivalent. While appreciating the

value of some kind of informal training, he publicly and frequently attacked

the formal, rigidly structured schools run on the lines of the French Academy.

He claimed they stifled initiative, encouraged adherence to outworn rules and

turned out too many students hoping for a career in Fine Art whose ambitions

were bound to be dashed in a society which generally cared little for native

artists.  While

working on his second major series, The Rake's Progress in 1734, Hogarth also

tried his hand at religious decorative painting, executing two murals for the

staircase of St Bartholomew's Hospital, the Pool of Bethesda and The Good

Samaritan. These he did free of charge, partly because it was for a charitable

purpose in an area of London he knew well and partly because there was a danger

of the commission going to an Italian painter, Jacopo Amigoni. Hogarth had

wanted to succeed in this more traditional form of High Art, but although he

later painted some more religious pictures, such as an altarpiece for St Mary

Redcliffe, Bristol, Hogarth was ill-at-ease in this kind of work.

While

working on his second major series, The Rake's Progress in 1734, Hogarth also

tried his hand at religious decorative painting, executing two murals for the

staircase of St Bartholomew's Hospital, the Pool of Bethesda and The Good

Samaritan. These he did free of charge, partly because it was for a charitable

purpose in an area of London he knew well and partly because there was a danger

of the commission going to an Italian painter, Jacopo Amigoni. Hogarth had

wanted to succeed in this more traditional form of High Art, but although he

later painted some more religious pictures, such as an altarpiece for St Mary

Redcliffe, Bristol, Hogarth was ill-at-ease in this kind of work.  In this

same year Hogarth suffered a major setback when he decided to sell his pictures

by auction to show that they were in as much demand as the imported 'Old

Masters'. The result of the first sale, and of a second held six years later,

was so disastrous that he tore down the gilded head of Van Dyck from above his

shop door.

In this

same year Hogarth suffered a major setback when he decided to sell his pictures

by auction to show that they were in as much demand as the imported 'Old

Masters'. The result of the first sale, and of a second held six years later,

was so disastrous that he tore down the gilded head of Van Dyck from above his

shop door.

0 Response to "British Great Artist William Hogarth Life"

Post a Comment