Vishnu in the Vedas

In the beginning, it was cold and dark.

In the beginning, it was cold and dark. Vishnu appeared on the horizon and filled the world with light. He took three steps dawn, noon and dusk and drove gloomy demons into the night.

With light came order, with order came life.

This is how the Vedic seers saw Vishnu: as a powerful life-bestowing, world-affirming sun-god who helped lndra and the devas become masters of the universe.

Lord of Yagna

The rishis felt the spirit of Vishnu reverberate in the yagna the mystical ceremony that helped the sun rise, the rain fall and the gods wrest control of the three worlds. Hymns were chanted, rich oblations of milk and butter offered, as fires blazed brilliantly in sacred altars. Thus was Vishnu's power invoked and divine favour sought.

It generated a rigid hierarchical caste-based society dominated by brahmanas and kshatriyas, where everyone was bound to his duty, his dharma. Vishnu, as lord of the sacrifice, was its foundation.

Cosmic Divinity

Not all were happy with these Vedic rituals; people toiled hard only to find their wealth being taken away by priests and kings who wished to please distant divinities. They sought a friendlier god, a god who solved their problems, shared his wealth and asked nothing in return. They found such a god in Nature — in the blue sky, in the black soil.

Some called him Bhagavan, the keeper of communal wealth, others called him Narayana, the deliverer of mankind. When he opened his eyes, day dawned; when he smiled, it rained. They saw him as a cowherd, a farmer, a warrior, a lover who freely offered everything he possessed. He was a single divine entity — the Ekantika — encompassing the whole cosmos within himself. He was Vasudeva, lord of the elements.

The Pancharatra sects extolled his virtues and invited all to adore, respect and worship him.

Vishnu and Bhagavatism

Around 500 B.C., the Buddha and the Jirta moved away from rituals prescribed by the Vedas in favour of moral and ethical lifestyles.

Many turned towards Bhagavatism — the worship of Bhagavan: the god who did not demand sacrifice, who believed in alzimsa and bhakti. This cult, with priests and simple rituals of its own, became so popular that the orthodox were forced to look favourably upon the god of the people: Bhagavan-Narayana-Vasudeva.

In him they recognised the Vedic Purusha from whose body the whole cosmos, including human society, had been created. They identified him with Vishnu, lord of the all-powerful sacrifice, and welcomed him within the Vedic fold.

In Narayaniya, Anugita and Harivamsa, composed around 300 B.C., Narayana and Vishnu had become one. Their union led to the flowering of Vaishnavism, a powerful religious force based on non-violence, devotion and adoration of the divine. Vishnu became the sole manifestation of godhead, greater than devas and asuras, not invoked by yagnas but pleased through pujas.

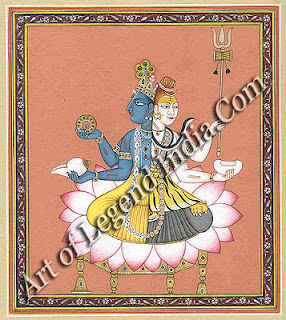

The mother-goddess Shree-Lakshmi, bestower of wealth and fortune, sought by both gods and demons, was seen as his chief consort, his shakti. Her presence made him more resplendent than ever. While he offered protection, she patronised growth. Together they became the divine foundation of human society.

Fusion through Vaishnavism

Devotees of Vishnu saw his spirit in great kings, sages and philosophers. They believed Vishnu manifested himself for the benefit of man.

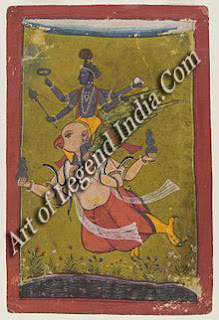

The pantheon of avatars evolved in the early centuries of the Christian era as Vishnu became increasingly identified with popular folk heroes (Rama, Krishna), legendary teachers (Parashurama, Vyasa, Kapila), ancient Vedic divinities (Trivikrama, Akupara, Emusha), tribal totems (lion, horse, eagle) and fertility gods (nagas). Early advocates of Bhagvatism, like Narada, Nara, Narayana and Sanat-kumars were also seen as avatars of Vishnu. The concept of avatars found the spirit of Vishnu in religious leaders like Sakyamuni Buddha, the Jain tirthankara Rishabha, the tan trik Dattatreya, bringing religious orders closer together and generating tolerance between different ways of life.

People could worship different gods believing that each one was an incarnation of one god — Vishnu. As a result, many cults and creeds merged with Vaishnavism.

Fusion with rival gods was not easy.

The middle ages saw the rise of Vaishnava and Shaiva rivalry: Shiva's favourite bel leaf was never offered to Vishnu while tulsi was kept out of Shaivite shrines. Peace was restored when Vaislulavas recognised Vishnu in the wild Bhairava and Shaivas saw Shiva in the gentle Datta. The two gods merged to become Hari-Hara.

Vishnu and World Religion

As hordes of invaders poured into India, destroying temples, crushing old ways of life, Vaishnavism helped adapt Hinduism to new ideas. Greeks found their hero Herakles in Krishna;the Zorastrian belief in the messiah Saoshyant was reflected in the prophecised descent of Kalki; the Puranic myth of Matsya saving Manu's ship appeared to be a variation of the Biblical tale of Noah's ark. Early Christian missionaries were convinced the legends of Krishna, the divine cowherd, were inspired by Christian gospels.

Vaishnavism also travelled to South-East Asia Suvarnaclvipa and Suvarnabhumi where everyone adore, kliv2 coNovred way6oz-7,od,N ishnu who rode on th( great solar-bird Garuda and brought rain. The Thai king of Siam declared that their capital Ayuthya was in fact tl real Ayodhya, and that they were the descendants of Rama himself.

King of the Cosmos

In India, Vishnu temples became repositories of wealth and centres of political power. Under the eye of the benign god-king Vishnu, the arts flourished and kingshi secured divine sanction.

Every ruler saw himself as the lord's avatar, born to uphold dharma within his tiny realm. Vishnu's resplend( chakra became the symbol of royal authority. A child boi with this mark on his body, the oracles said, was destin( to be king. The Gupta and Chalukyan emperors of India called themselves chakravartins bearers of the universi disc and tried to recreate Vaikuntha in their courts.

Focus of Philosophy

Assimilating political ideas, philosophical concepts and folk beliefs, Vaishnavism became popular amongst commoners and elite alike.

In Vishnu, yogis saw the purusha, the soul of the cosmos; in his divine dreams, tantriks found the powerful temptress may a-shakti, the substance of the world.

Vishnu was the fountainhead of karma-yoga, the doctrine of duty which was revered by every patriarch. His philosophical discourse, the Bhagavad Gita, gave solace to many troubled souls.

Vedantic scholars visualised life as the lord's game, leeln, and the world as his playground, his rangabhoomi. Different schools of thought led by acharyas like Shankara, Ramanuja, Madhava and Vallabha were united in the belief that Vishnu was the supreme being.

God of the People

Vaishriavism found a compromise between essential human equality and the traditional hierarchical world-view by emphasising more on devotion than on ritual.

Tales of Vishnu and the glory of his many avatars reached every corner of the land through epics like the Mahablinrata and the Ramayana. These were interpreted through song, dance, mime and drama, carved on rock, painted on cloth.

Vishnu as the noble Rama and the adorable Krishna fired the imagination of the masses. He was both dignified and delightful, a friend of the people capable of being whatever they wanted him to be: sage, warrior, lover, child.

Power of Bhakti

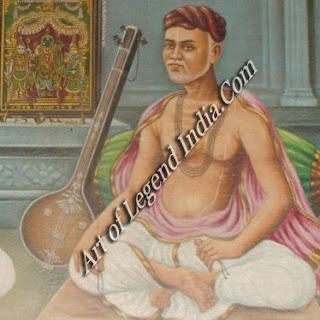

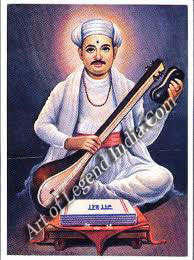

Adoration of Vishnu was an inspiration for the flowering of vernacular literature. The 12 Alvar saints of South India wrote four thousand Tamil hymns in the seventh century A.D. in praise of the lord.

Around the thirteenth century, Ramananda took the cult of ecstatic devotion to the north. Soon the fertile plains of Ganga and Yamuna were reverberating with songs of Krishna's love for Radha, composed by Surdas and Meerabai. In Ayodhya and beyond, Tulsidas enthralled the people with legends of Rama's valour and nobility, rewritten in the language of the people, Hindi.

Jnaneshwar's Marathi translation of the Gita and Tukaram's devotional poems, the abhangas, brought the word of the lord to the western corner of India. This was the period that saw Haridasa minstrels in the forests of Karnataka and Narsi Mehta in the villages of Gujarat. Everyone was singing songs about the blue god Krishna.

Around the same time, Shankardev took the lores of the Bhagavata Purana to Assam while Chaitanya danced in the streets of Bengal and Orissa enchanted by Krishna's Charm.

Bhakti carved out routes across India, linking North and South, East and West, taking pilgrims to distant lands where Vishnu danced and sang. It united Jambudvipa, the rose-apple continent of India.

Today, Vishnu's religion is a major force in Hinduism. Its history has been one of tolerance and assimilation, of adapting old ideas to new ones. Whatever form it took through the ages, it never lost sight of the fact that embodied in Vishnu was the answer to life's mysteries, its divinity and its delight.

0 Response to "The Vaishnava Heritage "

Post a Comment