Van

Gogh only painted for the last few years of his life, but his output was

enormous. He produced more than 800 canvases- working day and night, as if

aware of the short time allotted to him.

When

Van Gogh took the fateful decision to devote himself to art, in the bleak

coal-mining district of the Borinage in Belgium, he was already 27. He had

enjoyed sketching since childhood, especially views of the flat Dutch

countryside, with peasants labouring in the fields. But he had never learned to

paint in oils.

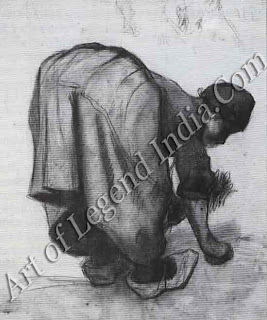

At

first he concentrated on drawing, employing a teach-yourself method of the time

known as the Bargues technique. He was very conscious of his deficiencies, and

eagerly associated with other painters, among them his relative Anton Mauve,

whom he visited in the Hague. But Vincent's fierce independence and stormy

temperament made it impossible for him to be a pupil he invariably argued with

his mentors.

In

Paris, he was inspired by the works of the Impressionists and their followers,

who had abandoned the methods of traditional art. Working out of doors instead

of in the studio, they ignored the idea of a 'finished' painting, in which all

colours were mixed on the palette to the correct shade, then laid down smoothly

on the canvas and finally varnished. Instead they used pure, bright colours

reds and blues, yellows, whites and greens and put down their paint in rough

brush strokes which gave the impression of light being reflected from natural

surfaces.

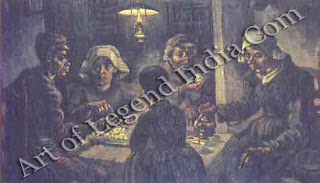

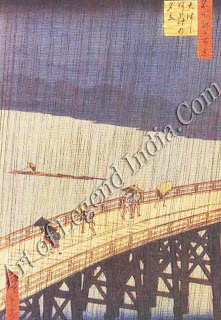

The

Impressionist method suited Vincent's purposes like them, he liked to work fast

and out-of-doors and he soon abandoned the sombre browns and blacks he had used

in Holland for paintings such as The Potato Eaters. In Paris, too, he was

inspired by Japanese art, which had recently become popular: hundreds of

wood-cut prints were readily available at a couple of francs apiece.

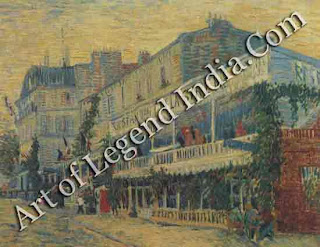

Vincent

saw Arles as a French version of Japan, and he travelled south in 1888 as if on

a personal mission to create a new movement in art. For over a year he worked

himself to breaking point, painting up to 16 hours a day. He had always worked

in frenzied bursts of activity, heedless of his deteriorating health, but now

he scarcely stopped to eat or drink, almost as if aware of the short lifespan

allotted to him.

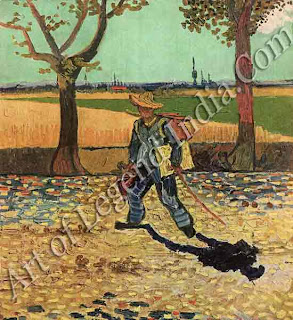

Every

day, through the blazing heat of the sum-mer, he would march out and set up his

easel. In the autumn he tried unsuccessfully to defy the fierce southern wind,

the Mistral, by pinning his canvas to the ground with heavy boulders. He would

paint all night, if necessary. To give himself enough light to paint The Café

Terrace, he stuck candles round his broad-brimmed hat and along the top of his

easel, and as the bemused Arlesiens looked on, he began to paint, 'absolutely

piling on, exaggerating the colour'.

Vincent

had always painted with thick layers of colour. Even for some of the Dutch

pictures he had applied paint so liberally that individual brushmarks were

ineffective, and he resorted to squeezing paint straight from the tube on to

the canvas, then modeling it 'a little' with his brush. Though he subsequently

learned to texture his surfaces with great sensitivity, this thickly-applied

paint known as impasto remained a hallmark of Van Gogh's art.

By

'exaggerating the colour', he explained to his brother Theo, he wished 'to

express myself forcibly'. Colours for Van Gogh did not merely describe objects,

but gave them meaning; and no colour meant more to him than yellow. In Japan it

symbolized friendship. It represented the glory of the sun and the golden wheat

in short; it was the colour of creation. Even in his night pictures yellow

plays a surprisingly important part. And in his famous painting Sunflowers he

created a whole painting with little colour other than yellow, a technical feat

almost without parallel.

Letters

to Theo requesting paint highlight Vin-cent's preference. They always start

with demands for large tubes of yellow and white paint. And the other colours

he used heavily, especially purples and blues, serve to accentuate the power of

yellow. His concern for colour extended to the framing of each work, and it was

not uncommon for him to give very explicit instructions to ensure the right

effect: on one occasion he asked for a royal blue and gold frame to be designed

especially for his canvas.

In the

months before his breakdown, Vincent produced some 200 paintings, including

about 50 portraits of his friends in Arles. Frequently he completed a painting

in a single day an amazing work-rate, even by the standards of the

Impressionists. 'I was right,' he wrote to Theo, 'to work at white heat as long

as it was fine.' And when his brother once hinted that his enormous output

might adversely affect the quality of his work, he retorted that 'Quick work

does not mean less serious work, it depends on one's self-confidence and

experience.

Under

the crushing weight of mental collapse, Van Gogh's self-confidence became badly

bruised. The swirling lines which distinguish all his late paintings seem to

echo the torment in his mind. Yet in this final phase of his career, Vincent

still worked at a punishing pace, producing a further 200 paintings in the last

year of his life. Among them was one of his greatest masterpieces the

Self-Portrait of 1890. One in a series of self-portraits equalled only by

Rembrandt's for their candour and penetration, it is a painting almost without

colour, dominated by pale, icy colours; warmed only by the orange-brown of the

artist's hair and beard.

The Bedroom at Arles

He

painted the room as simply as possible, with pure, harmonious colours and

strongly outlined shapes. The room is shown empty of people, but with an air of

expectancy: every-thing is painted in pairs. The two pairs of pictures, two

pillows, and especially the two chairs may well reflect Vincent's excitement

that his solitude was about to end.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Netherland Great Artist Van Gogh at Work"

Post a Comment