Although

he established himself primarily as an engraver, Hogarth also tried his hand at

other, more traditional, genres of art. He tried portraiture, the fashionable

'conversation pieces', decorative mural painting, and religious and

'Historical' painting. But although successful in these fields, he worked at

them as if to prove he could do them, and in order to give potential patrons

the opportunity to commission such works from him and from other British

artists should they wish to do so. His theoretical treatise, The Analysis of

Beauty in which he argued that beauty

resided in a kind of serpentine line was in part serious, in part mockery of

what he called 'the puffers in books' and in part self-mockery.

Although

he established himself primarily as an engraver, Hogarth also tried his hand at

other, more traditional, genres of art. He tried portraiture, the fashionable

'conversation pieces', decorative mural painting, and religious and

'Historical' painting. But although successful in these fields, he worked at

them as if to prove he could do them, and in order to give potential patrons

the opportunity to commission such works from him and from other British

artists should they wish to do so. His theoretical treatise, The Analysis of

Beauty in which he argued that beauty

resided in a kind of serpentine line was in part serious, in part mockery of

what he called 'the puffers in books' and in part self-mockery.

Hogarth's

perceptive portrayal of character and his bitingly satirical commentary on

18th-century life earned him comparison with Shakespeare England's greatest

student of the human comedy.

Everything

is copied from the book of nature, and scarce a character or action produced

which I have not taken from my own observations and experience.' Hogarth did

not write these words they were written by Henry Fielding in his preface to

Joseph Andrews but they could have been written by him and they show how close

his approach to his art was to that of Fielding in his novels. The 19th-century

writer and critic William Hazlitt placed Hogarth among the English comic

writers, rather than painters, and claimed: 'Other pictures we see, Hogarth's

we read.'

The

parallel can be drawn further. Hogarth's income was based on the sale of

engravings, not paintings, and on the principle of 'small sums from many', as

he himself put it. He was, in A Harlot's Progress, A Rake's Progress and other

series, appealing to a wide audience through published engravings in very much

the same way as the writer counted on the sale of his books, through

subscriptions and royalties, for his livelihood. The narrative series are the core

of Hogarth's art and represent his campaign to establish his independence as an

artist, as well as his challenge to the accepted forms of art. Through these

'modern moral subjects' which combined the styles and devices of High Art with

the content of low-life satire, Hogarth argued that the depiction of

contemporary life should be judged on the same level as the higher branches of

art, whose usual content was 'History', the Bible, or classical mythology and

allegory. Indeed, this had to be the basis of Hogarth's art if he was to sell

his works to a wide public, for Moll Hackabout (the harlot) and Tom Rakewell

(the rake) were understood and enjoyed by many people who could less easily

identify with mythological figures such as Apollo and Daphne. Hogarth chose

'the book of nature' as his subject matter because he wanted to appeal to

ordinary people as well as connoisseurs.

AN ORIGINAL STYLE

The new

subject matter required a new form. Hogarth's raw material had all the jerky,

informal, uncomposed character of everyday contemporary life, and his style

reflected this. The sources of this style are to be found in the popular

Italian engraved series of the 16th and 17th centuries, in the 17th-century

genre works of Netherlandish painters such as Teniers, Steen and Brouwer, in

the contemporary popular theatre in England, and in the actual everyday life

around him. 'I grew so profane', Hogarth wrote, 'as to admire nature beyond the

finest pictures.' By his method 01 memory training and graphic shorthand

process of linear abstraction which he developed in opposition to the

traditional methods of copying taught at St Martin's Lane he took in everything

around him so that it could be used later.

Hogarth's

early engravings were crude and uneven. Although he had trained as a silver

engraver, the transition to engraving on copper was not an easy one. Hogarth

recognized that he lacked the fineness of touch to reach the height of a

profession dominated by French engravers, and taught himself etching. This,

when combined with engraving, allowed him to produce a greater variety of

shading and hatching, giving the design depth and solidity, light and shade,

and turning it from a mere pattern into a picture. The publication of 12 large

engraved illustrations to Samuel Butler's Hudibras in 1726 marked a new

refinement of style, influenced by the French artist Coypel's illustrations to

Don Quixote which was published the year before.

A

Harlot's Progress, A Rake's Progress and Marriage a la Mode were all painted

with a view to attracting subscribers for the engravings which followed. Sadly,

the paintings for the first series have been lost, but in the other instances

the paintings appear more as genre pieces simple portrayals of manners while

the black-and-white prints convey a strong moral message.

Although

he established himself primarily as an engraver, Hogarth also tried his hand at

other, more traditional, genres of art. He tried portraiture, the fashionable

'conversation pieces', decorative mural painting, and religious and

'Historical' painting. But although successful in these fields, he worked at

them as if to prove he could do them, and in order to give potential patrons

the opportunity to commission such works from him and from other British

artists should they wish to do so. His theoretical treatise, The Analysis of

Beauty in which he argued that beauty

resided in a kind of serpentine line was in part serious, in part mockery of

what he called 'the puffers in books' and in part self-mockery.

Although

he established himself primarily as an engraver, Hogarth also tried his hand at

other, more traditional, genres of art. He tried portraiture, the fashionable

'conversation pieces', decorative mural painting, and religious and

'Historical' painting. But although successful in these fields, he worked at

them as if to prove he could do them, and in order to give potential patrons

the opportunity to commission such works from him and from other British

artists should they wish to do so. His theoretical treatise, The Analysis of

Beauty in which he argued that beauty

resided in a kind of serpentine line was in part serious, in part mockery of

what he called 'the puffers in books' and in part self-mockery.

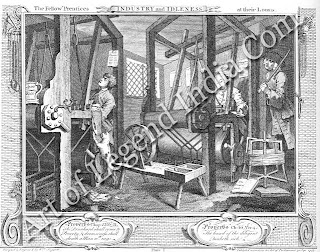

In

Hogarth's later work a more direct and moral stance is evident. The engravings

of Industry and Idleness, Beer Street and Gin Lane were cruder in execution

than previous engravings. This may have been a reaction against the refinement

of the less successful Marriage a la Mode series, engraved by French engravers,

but may also be explained by Hogarth's wish to convey a moral. Hogarth wrote:

'The fact is that the passions may be more forcibly experts by a strong bold

stroke than by the most delicate engraving [and] as they were addrest to hard

hearts, [I] have rather preferred leaving them hard to rendering them languid

and feeble by fine strokes and soft engraving.'

BITING SATIRE

His

last major series, The Election, reverted to the greater complexity of Marriage

a In Mode. The paintings themselves are perhaps the most richly and

successfully worked of all his paintings in oil, aside from some of the

brilliant portraits, such as Thomas Coram and The Graham Children. The Election

is in some ways a grand summing up of his art, painted late in his career,

aiming its satire at all sections of society, finding humour in everything, but

humour with a cutting edge of deep disillusionment with man's actions in a

corrupt society.

THE MAKING OF A MASTERPIECE

The Marriage, Contract

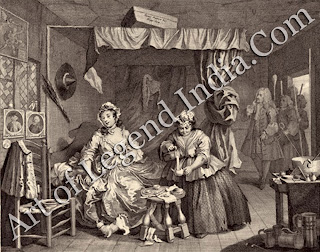

In

17431 Hogarth completed a series of six, paintings entitled Marriage-41a Mode,

which launched a savage attack on marriage for money. The pictures chart the

stages in the marriage between Viscount Squanderfield and his wife, from the

first financial wrangling between their parents to adultery and the eventual

deaths of the unhappy couple. The Marriage Contract is the first painting in

the series and shows the settlement being drawn up in the house of the groom's

father, who is hoping to replenish his diminishing fortune with the bride's

dowry. The bride and groom are indifferent to each other; the chained dogs.... symbolize

their plight.

Writer –

Marshall Cavendish

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "THE HOGARTH AT WORK "

Post a Comment