Netherlandish Great Artist Van Gogh - A Year in the Life 1888

Posted by

Art Of Legend India [dot] Com

On

11:38 PM

While

Van Gogh was furnishing his Yellow House in Arles, France was shaken by

political strife. In Paris, the ex-War Minister General Boulanger was wounded

in a duel with Prime Minister Flocquet, while Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany made

ominous threats of war. In Britain, Jack the Ripper stalked the streets of

London and heavy snow fell in mid-summer.

An

American astrologer predicted that this year would see the world's last days,

with the sun turning to blood and one universal carnage of death'. It started badly:

in January and February, deep snow and ferocious frosts brought most of Europe

to a standstill. The French astronomer Camille Flammarion, a recognized

authority on the end of the world, warned that the cold spell defied normal

explanation. In Birmingham, word went round that the Day of Judgement had

arrived. And in London, Edward Maitland wrote that the world had ended and

another was being born.

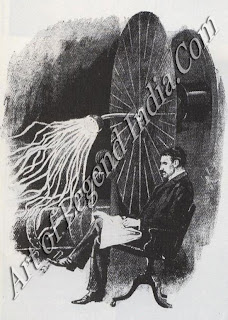

This

was right in one sense. The comforting edifice of nineteenth-century science

had begun to crumble. Michelson and Morley, experimenting in Berlin on the

speed of light, were destroying the idea of a fixed universe and paving the way

for Einstein's theory of relativity. In Vienna Ernst Mach, whose excellent work

on the speed of sound would give a new word to the language, insisted that it

was no longer possible to believe in absolute space or absolute time.

Men of

imagination, artists and writers, stepped into the breach, claiming their

insights were more valuable than those of the scientists. Fiction, declared

Robert Louis Stevenson, was closer to truth than 'the dazzle and confusion of

reality'. The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche summed the matter up more

pithily: 'The old God has abdicated, and from now on I shall rule the world.

Like

Van Gogh, Nietzsche felt threatened by approaching insanity. Yet there was much

to suggest the world around them was at least as mad as they were. When Van

Gogh arrived in Arles early in 1888 he found a city torn by violence and by

wild racial hatreds. Italian workmen were attacked by angry crowds and

half-strangled before local contractors were finally persuaded to stop

employing them. Throughout France, people became impatient with their dull

Republican government, and looked for something less rational, more flamboyant.

General Boulanger, until recently Minister for War, seemed ready to take over.

On 15

March, the day after the troubles in Arles had come to a head, Boulanger was

stripped of his army commission. For-bidden to go to Paris because of his

suspected intrigues against the Republic, he had dared to go there in disguise,

'wearing dark spectacles and affecting lameness'. The attempt to disgrace him

only made him more popular and he was elected to the Chamber of Deputies by two

separate constituencies for one of 'which he had not even been a candidate.

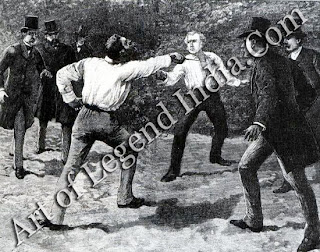

Boulanger

then tried to sweep away the Republic by getting the Chamber to dissolve itself

and challenged the Prime Minister, Charles Floquet, to a duel. When the duel

was fought Boulanger 'with blind impetuosity spitted himself on Monsieur

Floquet's sword', receiving a severe wound in the throat, while Floquet

sustained only minor injuries. Three days later a group of shocked and

peaceable deputies tried to get duelling banned, but were overwhelmingly

defeated. Boulanger's popularity continued to grow.

Colourful

swashbucklers, however impetuous, were more to French taste than the

frock-coated politicians of the Republic. This was partly because the Republic

no longer seemed respect-able. A deputy called Daniel Wilson, who had married

the President's daughter, had used his position to further his own interest as

a newspaper proprietor. There were other scandals in the offing, as politicians

became more and more enmeshed in the shady dealings of the company which had

been formed to build the Panama Canal.

Paris

was hit by a wave of strikes, as well as other forms of violence: anarchists

and communists waged an open gun battle in Pere la Chaise cemetery and an

artist, Eugene Dupuis, was killed by another artist in a duel about their

paintings. The bloodletting fell a long way short of the universal carnage

fore-cast by astrologers, but continued the collapse of the solid values of the

Republic.

One man

who did talk about carnage was the new German Emperor, Wilhelm II, who came to

the throne in June. Within a week of his accession he had two French newspaper

correspondents thrown out of Berlin, and embarked on a series of official

visits to countries that might be Germany's allies in any future war with

France.

In

August, the Kaiser made an uncompromising speech, saying that if France tried

to recover the German provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, more than 40 million

Germans would rather 'be left dead on the battlefield than see one stone taken

from them'. A few weeks later the imperial coat of arms above the German

consulate in Le Havre was torn down. The French government made hasty

apologies, but the Boulangists exulted.

Meanwhile,

Britain stood aloof. She refused to take sides, even when Germany challenged her

naval supremacy by laying down 28 new battleships. Instead she turned to such

dull matters as the establishment of County Councils and floating a new issue

of government stock.

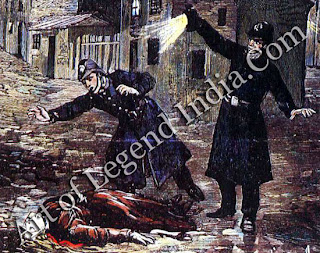

Britain's

own favourite prophet, the mediaeval wise woman known as Mother Shipton, had

said the world would come to an end when summer turned into winter; this

happened in 1888, with snow in June and July, but the British remained

un-perturbed. Yet they did see their own brand of sadistic violence, with Jack

the Ripper's murders in the East End of London.

As the

tension mounted, and Boulanger won election after election in an atmosphere

charged with anti-German delirium, his advent to power seemed inevitable. But

January 1889 saw a farcical anti-climax. Cheering crowds in Paris tried to

install him in the Presidential Palace, but Boulanger refused to budge. His

opportunity passed and the French Republic was saved, along with the peace of

Europe. The end of the old world, the predicted 'universal carnage of death',

was put off for 25 years, until the terrible days of August 1914.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Netherlandish Great Artist Van Gogh - A Year in the Life 1888"

Post a Comment