Jain Mythology

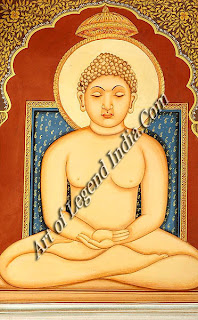

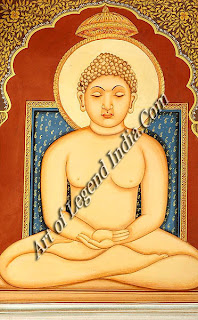

Mahavira,

the great teacher of Jain-ism in the present age, lived at the same time as

Buddha and like him was of the Kshatriya caste. He differed from Buddha,

however, in that his parents were already Jams, worshipping the Lord Parshva, whose

enlightenment resembles that of Buddha, though its message was different for

its core was the resistance to the urge to kill. Mahavira's parents therefore

welcomed and encouraged his calling. His birth in Benares was heralded by

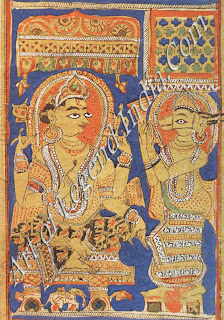

miraculous portents. His mother Trisala, also called Priyakarini, had a series

of sixteen dreams which foretold the birth of a son and his future greatness.

In these dreams she saw in turn a white elephant, a white bull, a white lion,

Sri or Lakshmi, fragrant Mandara flowers, the moon lighting the universe with

silvery beams, the radiant sun, a jumping fish symbolising happiness, a golden

pitcher, a lake filled with lotus flowers, the ocean of milk, a celestial

palace, a vase as high as Meru, filled with gems, a fire fed by sacrificial

butter, a ruby and diamond throne, and a celestial king ruling on earth. These

dreams were interpreted as portents of the coming birth of a great emperor or

of a Tirthankara, a being higher than a god, who spends some time as a teacher

on earth and whose soul is liberated by possession of the five kinds of

knowledge.

Shortly

thereafter the gods transferred the unborn child from the womb of Devananda, a

Brahmin's wife, to that of Trisala, and in due course Vardhamana was born. The

child was of exceptional beauty and developed great physical and spiritual

strength. When he was only a boy he overcame a mad elephant by grasping its

trunk, running up its head and riding on it. On another occasion, when a god,

to test his nerve, had lifted him up into the air, he tore the god's hair out

and beat him until he was released.

Shortly

thereafter the gods transferred the unborn child from the womb of Devananda, a

Brahmin's wife, to that of Trisala, and in due course Vardhamana was born. The

child was of exceptional beauty and developed great physical and spiritual

strength. When he was only a boy he overcame a mad elephant by grasping its

trunk, running up its head and riding on it. On another occasion, when a god,

to test his nerve, had lifted him up into the air, he tore the god's hair out

and beat him until he was released.

Vardhamana

obtained his enlightenment while sitting under an Asoka tree after two and a

half days of fasting. The gods had all gathered to watch the great event, and

at the moment of Vardhamana's enlightenment they bore him up and carried him in

a palanquin to a park, where they set him on a five-tiered throne and

acknowledged him as Mahavira. Here he stripped himself of all his clothes and

instead of shaving his head tore his hair out by the roots, for he was above

pain. As he cast off his clothes, they were caught by the god Vaisravana

(Kubera); one sect, the Digambaras (air-clad), believe that Mahavira wore no

clothes there-after, but the Svetambaras believe that Indra then presented him

with a white robe, for white robes, unlike all other personal possessions, do

not impede liberation of the soul by en-meshing it in the cycle of earthly

life.

Mahavira's

life was one of unexampled virtue and well illustrated his imperviousness to

physical pain and his detachment from worldly concerns. After his enlightenment

he gave away all his possessions and owned nothing beside the robe presented to

him by Indra. A Brahmin, Somadatta, reminded him that he had received nothing

when Mahavira distributed his wealth, and so the holy man gave him half the

robe. Somadatta could not wear the garment without the other half, but he

hesitated to ask for it and decided that he must steal it. The moment he chose

was when Mahavira was engaged in penances while sitting on a thorny shrub; but

Somadatta injured himself as he stealthily drew the robe away. Mahavira be-came

aware of the theft only when he had risen from his deep meditation but he

uttered no word of reproach, only making use of the incident as a lesson in his

teaching. On another occasion while he was meditating some herdsmen drove nails

into his ears and scorched his feet; but Mahavira maintained utter indifference

to such pain. Another time, when Mahavira was meditating in a field, a farmer

asked him to guard his bullocks. Mahavira took no notice of the farmer, who

returned some time later to find the bullocks had strayed away, and Mahavira

was still sitting there, answering nothing to his complaints. The farmer went

to search for his bullocks but returned empty-handed, only to find that the

bullocks were once again back in the field. The farmer immediately assumed that

Mahavira was trying to steal the animals, and began to twist his neck. But

Mahavira still made no sign, and would have been killed had Indra not

intervened and saved him. Ever after Indra assumed the role of Mahavira's

bodyguard, and so saved mankind from the effects of such sacrilege.

Mahavira's

life was one of unexampled virtue and well illustrated his imperviousness to

physical pain and his detachment from worldly concerns. After his enlightenment

he gave away all his possessions and owned nothing beside the robe presented to

him by Indra. A Brahmin, Somadatta, reminded him that he had received nothing

when Mahavira distributed his wealth, and so the holy man gave him half the

robe. Somadatta could not wear the garment without the other half, but he

hesitated to ask for it and decided that he must steal it. The moment he chose

was when Mahavira was engaged in penances while sitting on a thorny shrub; but

Somadatta injured himself as he stealthily drew the robe away. Mahavira be-came

aware of the theft only when he had risen from his deep meditation but he

uttered no word of reproach, only making use of the incident as a lesson in his

teaching. On another occasion while he was meditating some herdsmen drove nails

into his ears and scorched his feet; but Mahavira maintained utter indifference

to such pain. Another time, when Mahavira was meditating in a field, a farmer

asked him to guard his bullocks. Mahavira took no notice of the farmer, who

returned some time later to find the bullocks had strayed away, and Mahavira

was still sitting there, answering nothing to his complaints. The farmer went

to search for his bullocks but returned empty-handed, only to find that the

bullocks were once again back in the field. The farmer immediately assumed that

Mahavira was trying to steal the animals, and began to twist his neck. But

Mahavira still made no sign, and would have been killed had Indra not

intervened and saved him. Ever after Indra assumed the role of Mahavira's

bodyguard, and so saved mankind from the effects of such sacrilege.

When

Mahavira felt that he was about to die he spent seven days preaching to all the

rulers of the world, who had assembled to hear his holy words. They learnt of

the complicated metaphysics of Jainism and above all of the absolute

prohibition on killing, which led to the belief that the most virtuous life is

spent sitting still and fasting, as then a person runs no risk of injuring life

even in-voluntarily by swallowing or treading upon insects. On the seventh day

of his preaching Mahavira ascended a diamond throne bathed in super-natural

light. His death took place unseen by his assembled followers, for they all

fell asleep. All the lights of the universe went out as the great Mahavira

died, so his followers when they woke to darkness illuminated the city with

torches. Some believe that Mahavira died surrounded only by a few of the

faithful, but repeat that the moment of death was unseen.

When

Mahavira felt that he was about to die he spent seven days preaching to all the

rulers of the world, who had assembled to hear his holy words. They learnt of

the complicated metaphysics of Jainism and above all of the absolute

prohibition on killing, which led to the belief that the most virtuous life is

spent sitting still and fasting, as then a person runs no risk of injuring life

even in-voluntarily by swallowing or treading upon insects. On the seventh day

of his preaching Mahavira ascended a diamond throne bathed in super-natural

light. His death took place unseen by his assembled followers, for they all

fell asleep. All the lights of the universe went out as the great Mahavira

died, so his followers when they woke to darkness illuminated the city with

torches. Some believe that Mahavira died surrounded only by a few of the

faithful, but repeat that the moment of death was unseen.

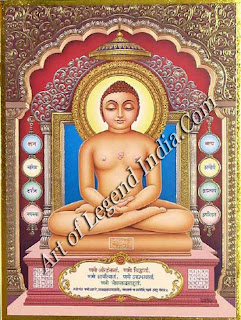

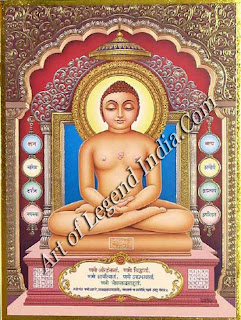

With

his death Mahavira became a Siddha, a freed soul of the greatest perfection,

being both omniscient and detached from karma, deeds on earth determining

rebirth. In addition he was declared a Tirthankara ('ford-finder'), the very

highest kind of Siddha, who has acquired the five kinds of knowledge, and has

been a teacher on earth. Every Tirthankara has to have passed through the four stages

through which a soul becomes free. Sadhus, ascetics, are at the lowest of these

stages; above them come Upakhyayas, teachers; next come Acharyas, heads of

orders; then Arhats, which are one stage higher and are freed souls which,

though omniscient, are still attached to the mortal condition.

The Jain Universal Cycle

The

Jams imagine time as an eternally revolving wheel. Its upward course,

Utsarpini, is under the influence of a good serpent, while its downward course,

Avasarpini, is under the influence of an evil one. The Utsarpini consists of

six progressively improving ages, while the Avasarpini consists of six periods

of progressively greater degeneracy, rather like the Hindu Mahayugas. But the

Avasarpini leads not to destruction but to the beginning of another Utsarpini.

Each

Avasarpini and each Utsarpini produce twenty-four Tirthankaras, one of which

was Mahavira. Tirthankaras cannot intercede on be-half of the faithful, for

there is no ultimate god; their value to humans is as objects of meditation.

The world is at present near the end of an Avasarpini. Of the Tirthankaras

which it has produced, many seem to have some connection with Hindu mythology.

Thus the first, Rishabadeva, attained Nirvana on Mount Kailasa, the abode of

Shiva; the seventh, Candraprabha, was born after his mother drank the moon; the

eleventh was born of parents who were both called Vishnu, and he attained Nirvana

on Mount Kailasa; and the twenty-second, Neminatha, was born in Dwarka and was

a cousin of Krishna. The other holy figures of Jainism would also seem from

their names to be connected with Hindu belief. They are twelve Chakravartin,

nine Narayana or Vasudevas, nine Pratinarayanas or Prativasudevas, nine

Balabhadras and, below them, nine Naradas, eleven Rudras and twenty-four

Kamadevas. Jain gods and demons are largely of Hindu inspiration, but there is

one import-ant difference: while demons can eventually work out their

salvation, gods exist on a different plane and cannot attain liberation without

first becoming human beings.

The Jain Universe

The

universe is symbolised by a head-less man divided into three: trunk, waist and

legs. The right leg contains seven hells where lesser gods are torturers of

souls, each one specialising in a particular brand of physical torture. The

left leg, Patala, contains ten kinds of minor deities and two groups of demons,

each kind inhabiting a different sort of tree. The black Vyantara demons

include the Pisachas, the Bhutas, the Yakshas, the Gandharvas and the

Mahoragas. The white Vyantara demons include the Rakshasas and the Kimpurushas.

The more fear-some of the two groups of demons are the Vana Vyantaras, which

are subdivided into Anapanni, Anapanni, IsiVayi, Bhutavayi, Kandiye,

Mahakandiye, Kohanda and Pahanga.

The

middle region of the universe is our world, and consists of eight ring-shaped

continents separated by eight ring-shaped oceans. These surround Mount Meru.

The

upper region contains in its lower part Kalpa, which is subdivided into sixteen

heavens. Above these is the Kalpathitha, subdivided into four-teen regions.

Gods of varying rank inhabit all these heavens, and they are divided both

geographically and by caste, with lndra as their king. Some of the gods take

pleasure in listening to the sermons of the sages, but not all are religious.

Above the heavens of Kalpathitha is the home of the Siddhas, Siddha Sila.

Writer

- Veronica Ions

Shortly

thereafter the gods transferred the unborn child from the womb of Devananda, a

Brahmin's wife, to that of Trisala, and in due course Vardhamana was born. The

child was of exceptional beauty and developed great physical and spiritual

strength. When he was only a boy he overcame a mad elephant by grasping its

trunk, running up its head and riding on it. On another occasion, when a god,

to test his nerve, had lifted him up into the air, he tore the god's hair out

and beat him until he was released.

Shortly

thereafter the gods transferred the unborn child from the womb of Devananda, a

Brahmin's wife, to that of Trisala, and in due course Vardhamana was born. The

child was of exceptional beauty and developed great physical and spiritual

strength. When he was only a boy he overcame a mad elephant by grasping its

trunk, running up its head and riding on it. On another occasion, when a god,

to test his nerve, had lifted him up into the air, he tore the god's hair out

and beat him until he was released.  Mahavira's

life was one of unexampled virtue and well illustrated his imperviousness to

physical pain and his detachment from worldly concerns. After his enlightenment

he gave away all his possessions and owned nothing beside the robe presented to

him by Indra. A Brahmin, Somadatta, reminded him that he had received nothing

when Mahavira distributed his wealth, and so the holy man gave him half the

robe. Somadatta could not wear the garment without the other half, but he

hesitated to ask for it and decided that he must steal it. The moment he chose

was when Mahavira was engaged in penances while sitting on a thorny shrub; but

Somadatta injured himself as he stealthily drew the robe away. Mahavira be-came

aware of the theft only when he had risen from his deep meditation but he

uttered no word of reproach, only making use of the incident as a lesson in his

teaching. On another occasion while he was meditating some herdsmen drove nails

into his ears and scorched his feet; but Mahavira maintained utter indifference

to such pain. Another time, when Mahavira was meditating in a field, a farmer

asked him to guard his bullocks. Mahavira took no notice of the farmer, who

returned some time later to find the bullocks had strayed away, and Mahavira

was still sitting there, answering nothing to his complaints. The farmer went

to search for his bullocks but returned empty-handed, only to find that the

bullocks were once again back in the field. The farmer immediately assumed that

Mahavira was trying to steal the animals, and began to twist his neck. But

Mahavira still made no sign, and would have been killed had Indra not

intervened and saved him. Ever after Indra assumed the role of Mahavira's

bodyguard, and so saved mankind from the effects of such sacrilege.

Mahavira's

life was one of unexampled virtue and well illustrated his imperviousness to

physical pain and his detachment from worldly concerns. After his enlightenment

he gave away all his possessions and owned nothing beside the robe presented to

him by Indra. A Brahmin, Somadatta, reminded him that he had received nothing

when Mahavira distributed his wealth, and so the holy man gave him half the

robe. Somadatta could not wear the garment without the other half, but he

hesitated to ask for it and decided that he must steal it. The moment he chose

was when Mahavira was engaged in penances while sitting on a thorny shrub; but

Somadatta injured himself as he stealthily drew the robe away. Mahavira be-came

aware of the theft only when he had risen from his deep meditation but he

uttered no word of reproach, only making use of the incident as a lesson in his

teaching. On another occasion while he was meditating some herdsmen drove nails

into his ears and scorched his feet; but Mahavira maintained utter indifference

to such pain. Another time, when Mahavira was meditating in a field, a farmer

asked him to guard his bullocks. Mahavira took no notice of the farmer, who

returned some time later to find the bullocks had strayed away, and Mahavira

was still sitting there, answering nothing to his complaints. The farmer went

to search for his bullocks but returned empty-handed, only to find that the

bullocks were once again back in the field. The farmer immediately assumed that

Mahavira was trying to steal the animals, and began to twist his neck. But

Mahavira still made no sign, and would have been killed had Indra not

intervened and saved him. Ever after Indra assumed the role of Mahavira's

bodyguard, and so saved mankind from the effects of such sacrilege.  When

Mahavira felt that he was about to die he spent seven days preaching to all the

rulers of the world, who had assembled to hear his holy words. They learnt of

the complicated metaphysics of Jainism and above all of the absolute

prohibition on killing, which led to the belief that the most virtuous life is

spent sitting still and fasting, as then a person runs no risk of injuring life

even in-voluntarily by swallowing or treading upon insects. On the seventh day

of his preaching Mahavira ascended a diamond throne bathed in super-natural

light. His death took place unseen by his assembled followers, for they all

fell asleep. All the lights of the universe went out as the great Mahavira

died, so his followers when they woke to darkness illuminated the city with

torches. Some believe that Mahavira died surrounded only by a few of the

faithful, but repeat that the moment of death was unseen.

When

Mahavira felt that he was about to die he spent seven days preaching to all the

rulers of the world, who had assembled to hear his holy words. They learnt of

the complicated metaphysics of Jainism and above all of the absolute

prohibition on killing, which led to the belief that the most virtuous life is

spent sitting still and fasting, as then a person runs no risk of injuring life

even in-voluntarily by swallowing or treading upon insects. On the seventh day

of his preaching Mahavira ascended a diamond throne bathed in super-natural

light. His death took place unseen by his assembled followers, for they all

fell asleep. All the lights of the universe went out as the great Mahavira

died, so his followers when they woke to darkness illuminated the city with

torches. Some believe that Mahavira died surrounded only by a few of the

faithful, but repeat that the moment of death was unseen.

0 Response to "Indian Jain Mythology "

Post a Comment