Indian Miniature Painting

"Drawing

the likeness of anything is called tasveer. Since it is an excellent source, both of study and

entertainment, His Majesty ... has taken a deep interest in painting and sought

its spread and development. Consequently this magical art has gained in beauty.

A very large number of painters has been set to work.

"From

the Ain-i-Akbari, written by Abu] FazI in the reign of Emperor Akbar

(r.1556-1605).

For a

period of over two hundred and fifty years, from the mid-sixteenth to the early

nineteenth centuries, there was a glorious flowering of painting in India. In

the Imperial atelier at Agra, the Emperor Akbar a man of taste as well as the

power and wealth with which to indulge it oversaw his artists as they created

the works he had commissioned. It was a busy place, this atelier of Akbar's,

where the great portfolios of the Hamza Nama and the Tuti Nama were painted and

masters like Basawan, Daswanth, Kesho, Miskin and Lal put brush to paper. They

were following in the traditions set by the Persian master painters, Mir Sayyid

Ali and Abdus Samad, brought to India by Akbar's father Humayun.

But

Akbar's artists were more than just copyists of the Persian style. They created

the synthesis between India and Persia, between the formally-structured and decorative

idiom of the Persians with its distinctive concept of perspective, and the

vital, colourful but somewhat two-dimensional ouvre then prevalent in India. In

the great kitabkhana at Fatehpur Sikri, Akbar's capital, they worked in teams

and their output was prolific. Lesser accomplished artists undertook the

arduous tasks of grinding the mineral pigments blue came from lapis lazuli,

Indian red from oxide of iron, a more brilliant red from cinnabar, yellow from orpiment

and gold from gold leaf. Thick handmade paper was repeatedly burnished on the

reverse side with an agate to make the surface glossy, and after the primer

coat of paint was laid, the master artist designed the scene and its colouring.

To traditional Indian colours like indigo and deep madder, were now added the

softer hues of delicate pistachio green and old rose. From this synthesis of

form, of colour and content, was born the first truly enduring Indian style,

one that was to spread to ateliers across the country, and influence artists elsewhere.

It was a seminal moment in the history of Indian painting.

But

Akbar's artists were more than just copyists of the Persian style. They created

the synthesis between India and Persia, between the formally-structured and decorative

idiom of the Persians with its distinctive concept of perspective, and the

vital, colourful but somewhat two-dimensional ouvre then prevalent in India. In

the great kitabkhana at Fatehpur Sikri, Akbar's capital, they worked in teams

and their output was prolific. Lesser accomplished artists undertook the

arduous tasks of grinding the mineral pigments blue came from lapis lazuli,

Indian red from oxide of iron, a more brilliant red from cinnabar, yellow from orpiment

and gold from gold leaf. Thick handmade paper was repeatedly burnished on the

reverse side with an agate to make the surface glossy, and after the primer

coat of paint was laid, the master artist designed the scene and its colouring.

To traditional Indian colours like indigo and deep madder, were now added the

softer hues of delicate pistachio green and old rose. From this synthesis of

form, of colour and content, was born the first truly enduring Indian style,

one that was to spread to ateliers across the country, and influence artists elsewhere.

It was a seminal moment in the history of Indian painting.

Seminal

though it was, Akbar's atelier was part of a much earlier and longer tradition

of Indian. Painting, a tradition that had spanned the course of more than a

thousand years and seen cave paintings, and paintings on palm leaves, wood and

cloth. The most famous examples, and deservedly so, of the art of ancient

Indian painting are the cave paintings at Ajanta. So much has been written

about them, about their supple and fluid lines, about their spatial and

volumetric richness, about their naturalism. But in the end, nothing prepares

you for their feeling of intense humanism, immediacy, and, yes, great joy. The

images are densely packed, but in the unmistakable and universal grace of their

contours and the warmth of the earth colours, there is a feeling of living,

breathing presences.

Echoes

of Ajanta are evident in the Buddhist palm leaf paintings of the

eleventh-twelfth century Pala kings of eastern India. The threads are next

picked up with Jain manuscripts, illustrated religious texts, a tradition which

flourished between the eleventh and sixteenth centuries. During the Sultanate

period of the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries came the Indo-Islamic

confluence; but because of the disparate styles Afghan, Turkish, Persian there

is no stylistic continuity. An outstanding work of this era is the Nimat Nama,

commissoned by Ghiyasuddin Khilji of Malwa. The vitality of this work, perhaps

the first illustrated cookbook in the world, draws equally from the spare

elegance of line, a Persian characteristic, interspersed with the warmth of

Indian textiles and poses. But the culmination of what could be called the

indigenous style is found in the paintings of the Chaurapanchasika group and

the folios of the Bhagavata Purana, among other examples, where the strong

contrasting colours of religious manuscript illustrations were combined with a

greater sophistication.

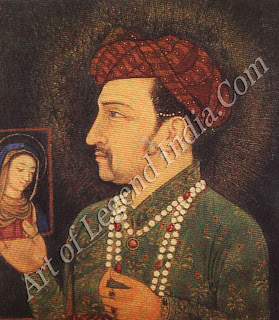

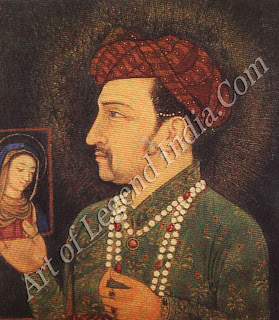

This

then was the backdrop of Indian painting at the time of Akbar, the platform from

which the next great impetus was to take place. Among the major contributions

of Akbar and his artists to the development of Indian art was the introduction

of portrait painting, a trend that was to be followed in later generations with

great enthusiasm by miniature painters, and more especially by their patrons.

But for the most part the paintings of that period, as of earlier periods, were

illustrations for books and text illuminations, and the art of painting was

closely associated with the art of the book. This was to change with Jahangir,

Akbar's son, already an active patron of the arts when he ascended the throne;

for his preference was for albums of single paintings. Jahangir had a deep and

abiding love for the beauties of nature; flowers, plants, birds and animals

fascinated him; and he commissioned his artists to paint them. Mansur was the

most talented of these painters, whose superb executions of birds and flowers

are intense and observant and have a grace and delicacy of touch.

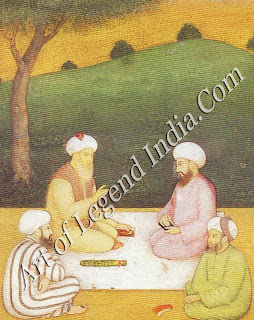

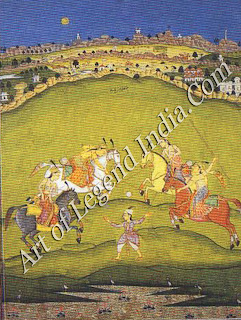

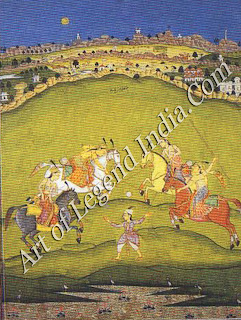

These

studies of nature were fresh and lyrical, but increasingly Jahangir turned to

more formal compositions, and court paintings, and this direction was followed

by his son and heir, Shah Jahan. There are now more portraits, scenes of

audience (durbar) and processions, almost as if the weight of empire made its

presence known in the pages of art. Nonetheless, many works of great artistic

merit were executed in this period, including hunt and battle scenes painted

with imagination and skill. A refinement of line and shading shows itself in

the miniatures of this time.

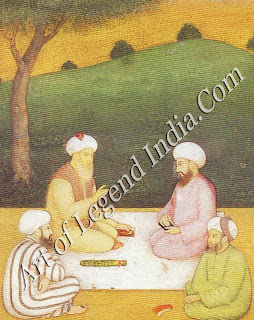

However,

active interest in art and its patronage went through ups and downs with

succeeding rulers, and indeed Aurangzeb, who ruled in the second half of the

seventeenth century, went so far as to dismiss his artists. Their dispersal led

to a wave of Mughal influence in the courts to which they now flocked. A

revival took place during the reign of Bahadur Shah; and a few years later, Muhammad

Shah known to history as a pleasure loving monarch who preferred the company of

women and buffoons to the more serious business of ruling also encouraged the

arts. The paintings of his period depict moonlight revels, music parties and

lovely concubines, themes executed in a mellow and graceful manner. But over

the years the absolute centrifugal power of the Mughal dynasty had declined,

and in 1738-39 the Persian invader Nadir Shah laid siege to Delhi and proceeded

to strip it of its riches. This caused another exodus of painters, who fled to

Lucknow, Patna, Hyderabad, the Punjab Hills and Rajasthan, and the future

history of miniature painting was to take place in these provincial courts.

Meanwhile,

far to the south in the Deccan, a parallel and contemporaneous development in

painting had taken place in the Islamic Sultanates of Bijapur, Golconda and

Ahmednagar. Here, in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, works

of great mastery and unmistakably Deccani identity had been created, an

interaction between Hindu traditions and the Muslim art of Persia, elegant

Iranian line and earthy Indian colour. It was a world apart; as Stella

Kramrisch writes "a kingdom of sated nostalgia, abandoned to scents and

dreams, lingering in flowers, glowing in colours, calm and deep..." When

the Deccan finally became subordinate to the Mughals, at the end of the

seventeenth century, the style adapted itself to new conventions, combining

Mughal, Rajput and Deccani elements.

The

painters who had moved to Rajasthan settled themselves in the Rajput kingdoms

of the area. Under the benign gaze of their new patrons, they gave fresh

impetus to an existing tradition, a tradition rooted in the pre-Mughal style,

strong of line and bold of colour. Local idioms were now combined with the

supple refinement of the Mughal School to produce works of vibrant tenderness

and intensity, each area having a distinct style and identity of its own. If

Mewar (Udaipur) had austere lines and bold, burning colours, then Bundi was

gentler, more lyrical, as seen in the famous Ragamala paintings. The soft colours

and melting forms of Bikaner found a counterpoint in the elegance of

Kishangarh. In the palaces of Kotah, of Jaipur, of Marwar (Jodhpur), and in the

thikanas or estates of the local aristocracy, painters put brush to paper to

record a variety of subjects and themes. .

The

pre-occupations of the artist were naturally those of his patron. Court and

hunt scenes abounded, a display of the mighty and valour of kings, who were

also depicted leading their armies atop splendidly canopied elephants, astride

magnificent horses or on camel-back. Individual portraits and illustrations

from legends and epics were also painted; but one of the most remarkable themes

was that of Ragamala, literally, the Garland of Ragas or musical modes. In

Indian raga, the aural experience of heard music arouses certain moods and

emotions, different ragas evoking different nuances ranging from the romantic

to the deeply religious. The visual expression of these emotions, these

feelings, richly delineated in colour and form, are the Ragamala paintings,

which Coomaraswamy has described as "profoundly imagined pictures of human

passion". Here is the ecstasy of love in union, as entwined lovers sway

gently on a swing; here too is the despair and pain of love in separation,

where the heroine pines for her absent lover against the poignant backdrop of

indigo clouds. The passages of seasons, the intensity of sacred devotion, are

all captured in the Ragamala paintings. Very often, the image of love is

symbolised by the figures of Radha and Krishna, whose yearning and seeking is a

metaphor for the soul's longing for God.

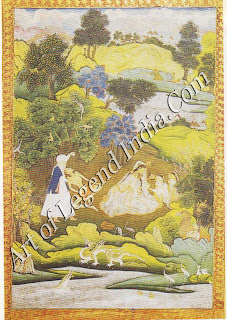

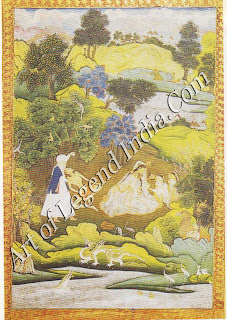

But the

zenith of the Radha-Krishna paintings was surely reached in the hills of the

Pahari kingdoms, far to the north, and with a climate and topography altogether

more temperate than that of Rajasthan. Here, amidst verdant slopes and

flowering trees, surrounded by women of beauty and grace, the artists of Guler

and Kangra created those masterpieces of refinement and delicacy that were to

delight and astonish the world. The concept of bhakti, that intensely personal

love between man and his god, found a beautiful visual expression in the Kangra

paintings of Krishna scenes. It is an enchanting luminosity that suffuses the

paintings; now the golden light of day that shimmers on dense foliage, now the

silver of moonlight reflected in river waters. It is a beautiful world of

nature, lyrically reflected in the feathery brush strokes of the artist, with

fine lines and glowing colours. It is also a world of beautiful humans with

chiselled features and large dark eyes, radiant with youth and innocence. For

its admirers, Kangra represents the most romantic form of Indian painting.

But the

zenith of the Radha-Krishna paintings was surely reached in the hills of the

Pahari kingdoms, far to the north, and with a climate and topography altogether

more temperate than that of Rajasthan. Here, amidst verdant slopes and

flowering trees, surrounded by women of beauty and grace, the artists of Guler

and Kangra created those masterpieces of refinement and delicacy that were to

delight and astonish the world. The concept of bhakti, that intensely personal

love between man and his god, found a beautiful visual expression in the Kangra

paintings of Krishna scenes. It is an enchanting luminosity that suffuses the

paintings; now the golden light of day that shimmers on dense foliage, now the

silver of moonlight reflected in river waters. It is a beautiful world of

nature, lyrically reflected in the feathery brush strokes of the artist, with

fine lines and glowing colours. It is also a world of beautiful humans with

chiselled features and large dark eyes, radiant with youth and innocence. For

its admirers, Kangra represents the most romantic form of Indian painting.

In the

nineteenth century, a new milieu was evolving. The nature and character of

patronage changed under the relentless pressure of history and colonialism. New

classes, new tastes were emerging. The Europeans brought in the concept of

realism and an altogether new palette of colours. Styles became precious,

ornamented, or over-heated, and while miniature painting did not die it simply

took different directions it never reached again the sublime heights that it

had attained under its great patrons.

Writer - Asharani Mathur

But

Akbar's artists were more than just copyists of the Persian style. They created

the synthesis between India and Persia, between the formally-structured and decorative

idiom of the Persians with its distinctive concept of perspective, and the

vital, colourful but somewhat two-dimensional ouvre then prevalent in India. In

the great kitabkhana at Fatehpur Sikri, Akbar's capital, they worked in teams

and their output was prolific. Lesser accomplished artists undertook the

arduous tasks of grinding the mineral pigments blue came from lapis lazuli,

Indian red from oxide of iron, a more brilliant red from cinnabar, yellow from orpiment

and gold from gold leaf. Thick handmade paper was repeatedly burnished on the

reverse side with an agate to make the surface glossy, and after the primer

coat of paint was laid, the master artist designed the scene and its colouring.

To traditional Indian colours like indigo and deep madder, were now added the

softer hues of delicate pistachio green and old rose. From this synthesis of

form, of colour and content, was born the first truly enduring Indian style,

one that was to spread to ateliers across the country, and influence artists elsewhere.

It was a seminal moment in the history of Indian painting.

But

Akbar's artists were more than just copyists of the Persian style. They created

the synthesis between India and Persia, between the formally-structured and decorative

idiom of the Persians with its distinctive concept of perspective, and the

vital, colourful but somewhat two-dimensional ouvre then prevalent in India. In

the great kitabkhana at Fatehpur Sikri, Akbar's capital, they worked in teams

and their output was prolific. Lesser accomplished artists undertook the

arduous tasks of grinding the mineral pigments blue came from lapis lazuli,

Indian red from oxide of iron, a more brilliant red from cinnabar, yellow from orpiment

and gold from gold leaf. Thick handmade paper was repeatedly burnished on the

reverse side with an agate to make the surface glossy, and after the primer

coat of paint was laid, the master artist designed the scene and its colouring.

To traditional Indian colours like indigo and deep madder, were now added the

softer hues of delicate pistachio green and old rose. From this synthesis of

form, of colour and content, was born the first truly enduring Indian style,

one that was to spread to ateliers across the country, and influence artists elsewhere.

It was a seminal moment in the history of Indian painting.  But the

zenith of the Radha-Krishna paintings was surely reached in the hills of the

Pahari kingdoms, far to the north, and with a climate and topography altogether

more temperate than that of Rajasthan. Here, amidst verdant slopes and

flowering trees, surrounded by women of beauty and grace, the artists of Guler

and Kangra created those masterpieces of refinement and delicacy that were to

delight and astonish the world. The concept of bhakti, that intensely personal

love between man and his god, found a beautiful visual expression in the Kangra

paintings of Krishna scenes. It is an enchanting luminosity that suffuses the

paintings; now the golden light of day that shimmers on dense foliage, now the

silver of moonlight reflected in river waters. It is a beautiful world of

nature, lyrically reflected in the feathery brush strokes of the artist, with

fine lines and glowing colours. It is also a world of beautiful humans with

chiselled features and large dark eyes, radiant with youth and innocence. For

its admirers, Kangra represents the most romantic form of Indian painting.

But the

zenith of the Radha-Krishna paintings was surely reached in the hills of the

Pahari kingdoms, far to the north, and with a climate and topography altogether

more temperate than that of Rajasthan. Here, amidst verdant slopes and

flowering trees, surrounded by women of beauty and grace, the artists of Guler

and Kangra created those masterpieces of refinement and delicacy that were to

delight and astonish the world. The concept of bhakti, that intensely personal

love between man and his god, found a beautiful visual expression in the Kangra

paintings of Krishna scenes. It is an enchanting luminosity that suffuses the

paintings; now the golden light of day that shimmers on dense foliage, now the

silver of moonlight reflected in river waters. It is a beautiful world of

nature, lyrically reflected in the feathery brush strokes of the artist, with

fine lines and glowing colours. It is also a world of beautiful humans with

chiselled features and large dark eyes, radiant with youth and innocence. For

its admirers, Kangra represents the most romantic form of Indian painting.

Very good website, thank you.

Handmade Brass Puja Bell

Order Handicrafts Product

Handicrafts Product Online

Joining English Kranti was one of the best decisions for my personal growth. The classes are well-planned and focus on both communication and confidence building. Trainers provide personal attention and useful feedback, which really helps in improvement. The practice sessions are engaging and boost self-confidence. If someone is looking for effective Personality development classes in Udaipur English Kranti is the right choice. I noticed visible changes in my speaking skills, body language, and overall personality. The positive environment encourages you to speak without fear. I highly recommend English Kranti to students, job seekers, and professionals who want to enhance their personality and communication skills.