Frenchish Great Artist Paul C'ezanne - The Geometry of Nature

Posted by

Art Of Legend India [dot] Com

On

3:19 AM

Toiling

alone on the hillsides of Provence, Cezanne developed a new way of painting the

natural world. He sought beneath the surface for the essential elements of

nature's geometry.

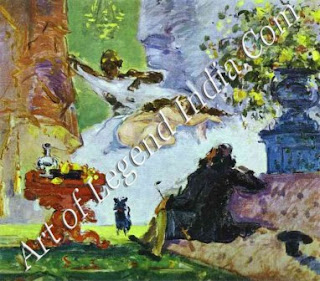

'In all

the history of art, there has seldom been a painter whose early style differed

so greatly from that of his maturity', wrote the critic Rene Huyghe. Indeed, it

is hard to see any resemblance between the subtle, deliberately balanced

canvases of Cezanne's mature years, and the morbidly violent and erotic

pictures of his twenties, which often give the impression of having been

created in frenzy. For a time Cezanne abandoned the brush for a palette knife,

slapping on the paint. And as if to emphasize his personal involvement with

these fantasies, he often included a picture of himself within the painting: he

appears as the balding onlooker in A Modern Olympia.

Gradually,

Cezanne turned to the outside world for inspiration. As early as October 1866,

he wrote to his friend Emile Zola that 'pictures painted inside, in the studio,

will never be as good as those done outside'. But, oddly enough, it was not

until the 1870s that he followed up this insight. By that time, Pissarro and

his friends Monet and Renoir had discovered most of the techniques of

Impressionism, which Cezanne was to learn during his association with Pissarro

at Pontoise.

Impressionism

turned Cezanne into an outdoor painter a dusty, weather-beaten figure with a

broad-brimmed hat and heavy boots who tramped the countryside every day with

his pack slung across his shoulders. But though Cezanne never abandoned this

way of working, he soon became dissatisfied with some aspects of Impressionism.

He had a stronger sense of construction than his contemporaries, whose

paintings tended to dissolve objects in a play of dazzling light. He wanted to

retain the brightness and freshness of Impressionism but make of it 'something

solid and durable, like the art of the museum'.

He

adapted the distinct, blocky dash-like strokes, which broke up forms in

Impressionist paintings, using them instead to construct form. In the late

1870s, they became a repeated pattern of regular oblongs of paint, arranged in

parallel across his pictures, as in the Chateau at Medan. As well as giving

solidity to the forms in the picture, the repetition and regularity of these

paint marks emphasized the painting's surface unity.

Indeed,

as his personal style developed, Cezanne became determined that the flat,

two-dimensional nature of the painting should not be denied. He was not

interested in imitating the real world: he called his paintings 'constructions

after nature', in which essential elements from the three-dimensional world

were reassembled on a flat canvas. And to represent the real spatial

relationships between objects without breaking up the flatness of the canvas,

he devised his own method: the so-called 'flat-depth', which has been called

'one of the miracles of art'.

Cezanne

achieved his aim in various ways: by overlapping patches of paint so that one

appears to be in front of the other, by depicting objects from several angles

at once, apparently pulling them towards the surface, and by exploiting the

visual phenomenon whereby warm colours (reds and yellows) appear to come

towards us, while cold colours (blues and greens) seem to recede. And instead

of modeling his subjects with light and shade, Cezanne 'modulated' form with

colour.

This

unique system of painting did not come to Cezanne in a flash of inspiration: he

developed it slowly and laboriously the same way, in fact, that he painted each

picture. He would work on a painting for months, sometimes years, always

addressing the entire canvas simultaneously, not painting it section by section.

A dab of colour here would be balanced by another colour there, and so on,

building up the painting as a coherent whole. This painstaking process was at

the opposite extreme to his early emotional outpourings.

Yet in

Cezanne's later pictures, from the 1880s onwards, a new kind of expressive

freedom emerged. Where his first paintings had been overstated and clumsily

executed, these late paintings show the economy and subtlety that comes only

when an artist has mastered his medium. His paint became thinner, his colours

richer, and the rigidly regular strokes of paint became more loosely painted

patches of colour often set beside patches of bare canvas, as in The Turn in

the Road. It was a revolutionary way of painting, which laid the foundations

for the major art movements of the 20th century, from Cubism to abstract art.

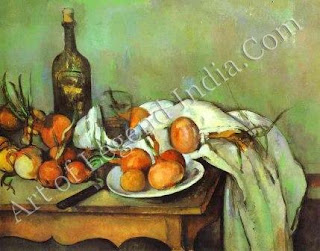

Perhaps because of his strong desire to organize nature, Cezanne became one of

the great masters of a type of painting that had largely fallen into neglect the

still-life. He could choose and arrange natural elements himself, not

hesitating to wedge them or prop them up to secure exactly the arrangement he

wanted.

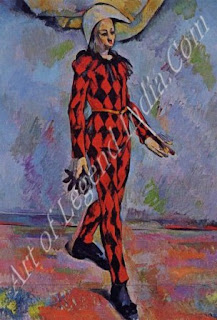

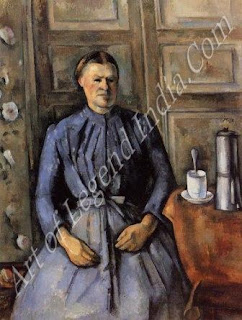

Human

beings were irritatingly more difficult to arrange. 'Apples don't move!'

Cezanne once snapped at a weary sitter. Impatient and uneasy with people, until

late in life he could only tolerate his own family or close friends as portrait

models.

Cezanne

was even less able to cope with nude models, and his bathing scenes were

painted with the aid of photographs. These scenes represent a more openly

emotional strain in his work, probably related to the painted orgies and

violence of his youth. But as an artist, at least, Cezanne had tamed his

demons, and in a picture such as The Great Bathers the figures have become part

of the landscape, sharing its beauty and order.

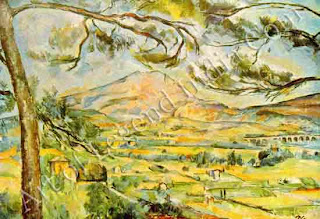

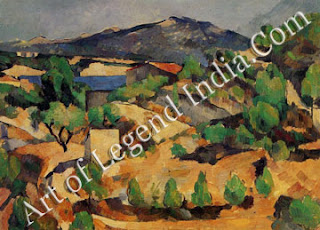

Particular

places were important to Cezanne. He painted almost exclusively in the environs

of Paris and in his native South. The hard outlines of the Provencal landscape

encouraged his quest for a 'solid and durable' art: 'I am passionately fond of

the contours of this country,' he wrote. He painted certain places many times

above all Mont Sainte-Victoire, the mountain that dominates some 60 of

Cezanne's paintings.

Even at

the end of his life, Cezanne was still advancing yet he still grumbled. 'I am

beginning to glimpse the Promised Land,' he wrote 'but why so late and with

such difficulty?'

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Frenchish Great Artist Paul C'ezanne - The Geometry of Nature "

Post a Comment