Constable's

Suffolk

Constable painted Suffolk in its golden

age, when high farm prices brought boom years for farmers. But country life was

changing. In the background of his landscapes, the old world was giving way to

the new.

Constable painted Suffolk in its golden

age, when high farm prices brought boom years for farmers. But country life was

changing. In the background of his landscapes, the old world was giving way to

the new.

Today, Constable's paintings of the Suffolk

landscape seem like portraits of a golden age. Cattle and sheep graze in the

lush meadows; the corn stands high in pleasant fields bordered by hedgerows and

five-barred gates; a sturdy band of labourers work peacefully through an

endless summer. The barges slipping quietly down the Stour make a colourful

focus for this idyll.

But to Constable himself, a corn merchant's

son surveying the family lands with a close interest in the business of

farming, the pictures are a detailed record of a specific time and place. The

Suffolk he portrays was on the crest of an agricultural boom. And the canals in

the years before the railways reached East Anglia - were the main arteries of

trade, carrying grain from the wetlands’ of Suffolk to the markets of London.

In Constable's lifetime, Suffolk was

changing rapidly. Indeed, the scenes he painted would scarcely have been

familiar to a farmer from the 17th century. Then, and ever since the Middle

Ages, the mainstay of the economy had been wool, not corn. The majestic tower

of Dedham Church, in the heart of Constable Country, had marked the town as the

centre of the local wool trade, and an important weaving town.

The mills at Flatford and Dedham, like

those in almost every other village along the course of the Stour, had

originally been built for fulling, or cleansing, wool. But in the 18th century,

when the weaving trade moved north to Derbyshire and Lancashire, and England's

rising population pushed up the demand for bread, Suffolk farmers turned from

sheep to grain. Then the mills were adapted for grinding the corn; and to carry

the flour to the coastal ports of Harwich and Felixstowe, the Stour was made

navigable as far up-river as Sudbury. A number of locks were built with massive

timber spars. Cuts and wharves were constructed beside each of the mills.

BARGES

ON THE STOUR

The ground corn was loaded on to lighters,

which were also built entirely of wood in a basin at Flat-ford. They were some

47 feet long and 10 feet 9 inches wide, and designed to travel in pairs, of

which the front one contained a cabin for the bargeman and his family. Powerful

draught horses usually of the Suffolk Punch breed towed the barges downstream

at a speed of about two miles an hour: in many places the towpath alternated

between the two banks and the horses had to be ferried across on the barge. At

Brantham Tidal Lock, the lighters were floated on the tide for three miles down

to Mistley Quay from where the corn was shipped via the larger Essex ports to

London or the north.

Constable's father, Golding, had profited

greatly from the agricultural boom. He built up a prosperous business based on

corn milling: he owned Flatford Mill and the windmill on East Bergholt Heath,

and he ran Dedham Mill on behalf of some local businessmen. By 1776, when John

was born, he had become wealthy enough to ac-quire one of the largest estates

in East Bergholt an area of 93 acres which contained a mixture of arable and

pasture land, a flower garden and kitchen gar-dens. The farm was never his main

source of in-come, but his family could be self-sufficient in food. To the

social duties which Ann Constable al-ready had as the wife of a successful

businessman were now added those of a wealthy farmer's wife. She managed the

poultry yard, made sure the milk-maids got up before sunrise and supervised the

butter- and cheese-making.

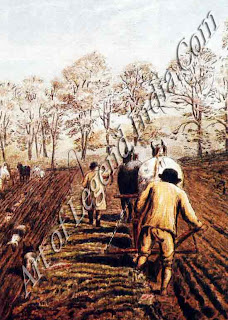

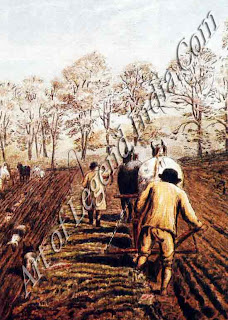

PLOUGHING

CONTESTS

The Constables acquired their land on the

Suffolk-Essex border at a time when the two counties were among the best-farmed

in England. Many of the larger land-owners had pioneered new systems of

crop-rotation and improved machinery. Their fields were ploughed by horse-drawn

wheel ploughs driven by men who to judge from the many ploughing matches took

great pride in their job. These contests encouraged rivalry amongst them, and

they welcomed improvements to the design of their ploughs. Seeds were planted

in the straight furrows with the aid of the seed-drill invented by Jethro Tull.

In the 1780s, during Constable's boyhood,

most of those living around East Bergholt were using the three-year system of

crop rotation devised by Lord 'Turnip' Townshend of Norfolk. Under this

sys-tem, turnips were sown in the first summer to pro-vide fodder for the

animals in winter. In the following spring a mixture of barley and clover was

sown. The barley was harvested later in the year, but the clover was left,

partly to provide more winter fodder for the animals and partly to be cut for

hay in the following summer. At the end of this third summer the fields were

ploughed and manured. Local manure was supplemented by Kentish chalk and London

manure brought to the Stour estuary by the grain vessels. Winter wheat was then

sown and harvested in time for the next sowing of turnips in the summer.

Traditional methods were still used for

many of the seasonal jobs. In the early summer, teams of men working in lines

used scythes to mow the long grass of the water-meadows. The grass was then

left to dry and, if the weather was fine, it was stacked after five to seven

days. At the end of the summer, everyone in the local community was involved in

the job of harvesting the corn. Teams of men, again working in lines, reaped

the corn with sickles, and their wives helped pitchfork the cut corn on to the

horse-drawn carts.

LORD OF

THE HARVEST

Each team of mowers or reapers elected one

of their number to act as leader or foreman. Known as the 'lord', he agreed on

terms with the farmer and ensured that the harvest was done properly. Every man

was expected to keep his allotted place in the line, and if he fell behind or

did shoddy work, he was fined by the 'lord'. Once gathered, the corn was

traditionally threshed by men and women with flails. However, a hand-powered

threshing machine was invented in the 1780s, and it soon became a common sight

in Suffolk.

Each team of mowers or reapers elected one

of their number to act as leader or foreman. Known as the 'lord', he agreed on

terms with the farmer and ensured that the harvest was done properly. Every man

was expected to keep his allotted place in the line, and if he fell behind or

did shoddy work, he was fined by the 'lord'. Once gathered, the corn was

traditionally threshed by men and women with flails. However, a hand-powered

threshing machine was invented in the 1780s, and it soon became a common sight

in Suffolk.

It is the traditional landscape that is

recorded in Constable's paintings, most of which were based on his visits

between 1802 and 1814, enriched by his boyhood memories. They reflect a time

when small and large landowners existed comfortably side-by-side, and honoured

their obligations to the landless labourers. On some farms the poorer workers

might be given a bed in the farmer's house and supper at his table. On almost

every farm the men who brought in the harvest were fed at the farmer's expense

and received generous quantities of ale while working in the fields. The day

the last cart-load of corn, decorated with flowers and green boughs, was taken

back to the farm, the whole community sat down together to a 'harvest home'

supper. Employer and employee alike celebrated with dancing, singing and drinking.

But this brief 'golden age' was not to last

even through Constable's own lifetime. During the wars against Napoleon, the

French blockade of the Channel ports prevented European corn from reaching

England, and even with the new methods, English farmers could not make up the

shortage. The price of corn quadrupled between 1792 and 1812 and throughout the

country farmers enclosed and cultivated more and more land. The fields around

East Bergholt had long been en-closed, but there was still scope for the wealthier

farmers to increase their holdings.

And as Constable himself noted in his

letters, they also took over the lands of the poorer farmers and divided up the

common lands amongst them-selves. This was a savage blow to the landless

labourers, who were already hard-pressed to pay the rocketing prices for their

bread. The common lands had traditionally been used by the poor peas-ants to

graze their animals; now many were reduced to total destitution. And their

situation did not improve, even after the victory at Waterloo in 1815, for the

change in land ownership was permanent. Labourers rioted frequently in the

black years that followed, and with rick burning an almost nightly occurrence,

the world Constable had loved was literally going up in flames.

And as Constable himself noted in his

letters, they also took over the lands of the poorer farmers and divided up the

common lands amongst them-selves. This was a savage blow to the landless

labourers, who were already hard-pressed to pay the rocketing prices for their

bread. The common lands had traditionally been used by the poor peas-ants to

graze their animals; now many were reduced to total destitution. And their

situation did not improve, even after the victory at Waterloo in 1815, for the

change in land ownership was permanent. Labourers rioted frequently in the

black years that followed, and with rick burning an almost nightly occurrence,

the world Constable had loved was literally going up in flames.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Constable painted Suffolk in its golden

age, when high farm prices brought boom years for farmers. But country life was

changing. In the background of his landscapes, the old world was giving way to

the new.

Constable painted Suffolk in its golden

age, when high farm prices brought boom years for farmers. But country life was

changing. In the background of his landscapes, the old world was giving way to

the new.  Each team of mowers or reapers elected one

of their number to act as leader or foreman. Known as the 'lord', he agreed on

terms with the farmer and ensured that the harvest was done properly. Every man

was expected to keep his allotted place in the line, and if he fell behind or

did shoddy work, he was fined by the 'lord'. Once gathered, the corn was

traditionally threshed by men and women with flails. However, a hand-powered

threshing machine was invented in the 1780s, and it soon became a common sight

in Suffolk.

Each team of mowers or reapers elected one

of their number to act as leader or foreman. Known as the 'lord', he agreed on

terms with the farmer and ensured that the harvest was done properly. Every man

was expected to keep his allotted place in the line, and if he fell behind or

did shoddy work, he was fined by the 'lord'. Once gathered, the corn was

traditionally threshed by men and women with flails. However, a hand-powered

threshing machine was invented in the 1780s, and it soon became a common sight

in Suffolk.  And as Constable himself noted in his

letters, they also took over the lands of the poorer farmers and divided up the

common lands amongst them-selves. This was a savage blow to the landless

labourers, who were already hard-pressed to pay the rocketing prices for their

bread. The common lands had traditionally been used by the poor peas-ants to

graze their animals; now many were reduced to total destitution. And their

situation did not improve, even after the victory at Waterloo in 1815, for the

change in land ownership was permanent. Labourers rioted frequently in the

black years that followed, and with rick burning an almost nightly occurrence,

the world Constable had loved was literally going up in flames.

And as Constable himself noted in his

letters, they also took over the lands of the poorer farmers and divided up the

common lands amongst them-selves. This was a savage blow to the landless

labourers, who were already hard-pressed to pay the rocketing prices for their

bread. The common lands had traditionally been used by the poor peas-ants to

graze their animals; now many were reduced to total destitution. And their

situation did not improve, even after the victory at Waterloo in 1815, for the

change in land ownership was permanent. Labourers rioted frequently in the

black years that followed, and with rick burning an almost nightly occurrence,

the world Constable had loved was literally going up in flames.

0 Response to "British Great Artist John Constable - Constable's Suffolk "

Post a Comment