A Year in the Life 1812

A Year in the Life 1812

While

Constable was sketching in the depths of Suffolk, dramatic news was breaking in

the outside world. The king had gone mad, and power went to his fashionable son

the Prince Regent; the prime minister was shot in parliament; the long war

against Napoleon continued with disastrous consequences for the British

economy. It was a year of three-day weeks, riots and the waltz.

By the

beginning of 1812 Britain had been at war against Napoleon for the best part of

20 years. In all this time, she had totally failed to break French domination

of the continent. Again and again she had encouraged other European nations to

challenge French supremacy, only to see them defeated and reduced to the status

of satellite kingdoms under the overlordship of the Emperor Napoleon.

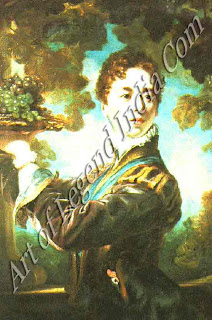

Now at

last there seemed to be hope. Friction between Napoleon and the Tsar Alexander

looked like dragging France into an exhausting war with Russia. Nearer home a

British army under Wellington was breaking out from bridgeheads in Portugal to

begin an invasion of Spain. In domestic affairs, too, change was in the air.

King George III had lapsed into permanent insanity and power had passed to his

son the Prince Regent the leader of fashion and an outspoken critic of his

father's conservative attitudes.

In

London, however, the year began in gloom. January brought some of the darkest

days the capital had ever known. Shops and public offices had to be lit

throughout what should have been the daylight hours and it proved impossible to

read a newspaper, even at an open window, without artificial light.

PROPHETS OF DOOM

Persons

in the streets', it was reported, 'could scarcely be seen in the forenoon at

two yards distance'. In the House of Commons, as the darkness deepened,

prophets of doom gained the upper hand. A brace of radical Whigs proposed an

Address to the Regent alleging that the country was on the brink of total

collapse. The Tory government's stubborn determination to wage economic warfare

against Napoleon was disastrous.

There

was some truth in the charges. By cutting off all trade with Napoleon's

fortress Europe, the government was under-mining the very prosperity upon which

any kind of war must depend. Many industrial areas had been working a three-day

week for months past and starving labourers were taking the law into their own

hands. Riots had become commonplace some of them apparently orchestrated by the

semi-legendary figure of Ned Ludd, who issued proclamations from his 'office'

in the depths of Sherwood Forest.

The

only hope seemed to lie in the Regent. So far he had been prevented by law from

making permanent changes in the government, but many people believed that when

this limitation was removed he would throw out the Tories and form a new

administration to bring back peace and prosperity. Their hopes were dashed. The

restrictions on the Regent's power were removed in February, but no change

came.

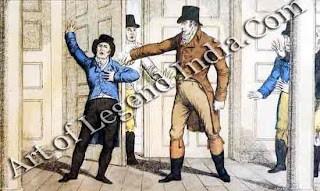

MURDER IN THE COMMONS

Then in

May the Prime Minister was assassinated and the Commons passed a vote of

censure on his Tory successor and forced him to resign. Still the Regent would

not move. The Tories came back, the war continued, the portents of disaster,

both man-made and heaven-sent, grew more ominous.

In the

Channel the Royal Navy was hit by an unprecedented electric storm which

'shivered masts from end to end' and killed or wounded many sailors. In London

the road tunnel newly dug at Highgate fell in with a terrifying roar workmen

said they had been waiting for it to happen, because of the poor quality of the

bricks they were forced to use and in the West Country there was an earthquake.

The weather grew so bitter that when the London to Bath stagecoach arrived in

Chip-penham two of the passengers were found to be stone dead and a third 'with

faint signs of animation left, died the following morning.

STARVATION TACTICS

The

Regent and his ministers clung doggedly to their policies of war and

repression. The only hopeful sign was the attendance of three of the Prince

Regent's brothers at a meeting held in May 'to consider the distressed state of

the labouring poor'. All that resulted, however, was the opening of a

subscription fund and the appointment of a committee.

The

Regent and his ministers clung doggedly to their policies of war and

repression. The only hopeful sign was the attendance of three of the Prince

Regent's brothers at a meeting held in May 'to consider the distressed state of

the labouring poor'. All that resulted, however, was the opening of a

subscription fund and the appointment of a committee.

Napoleon

for his part had relaxed a ban on the import of goods into Europe, so that

British manufacturers were starting to re-cover old markets and pick up more

business, but the British still sought to starve the continent into submission.

The news-papers noted with some satisfaction the straits to which the

foreigners had been reduced: a mill in Copenhagen to grind down bones and make

'a nourishing broth', and attempts in Germany to make sugar substitutes out of

apples, turnips and the bark of trees.

In

August observers along the Channel coast were alarmed by freak tides caused,

the experts decided, 'by some great convulsion of Nature'. Then it was learned

that at Giessen in Ger-many, at the very heart of Napoleon's Europe, a

twelve-acre wood had sunk deep into the earth, leaving 'a frightful chasm'.

Coincidentally, a national day of prayer and thanksgiving was held in Britain

when this sinister abyss was at its deepest, before the wood began equally

inexplicably to rise up again.

THE WANTON WALTZ

'Of thy

great mercy', the British prayed, 'open the eyes of our blinded and infatuated

enemies, that they may see and under-stand the wickedness they are working.'

But there was no sign that the prayer had been heard. On the contrary, the

French and their satellites succeeded in importing into Britain one of their

most shameless dances, the waltz. 'It wakes to wantonness the willing limbs'

wrote Byron, while outraged moralists condemned the new dance roundly and

delighted caricaturists showed ballrooms full of couples doing rather more than

dancing to the music.

The

rich and the powerful went on dancing but the war they were waging was now

neither successful nor popular. Wellington fell back from Spain into Portugal

and when the Regent drove to open Parliament he was greeted by a sullen silence

in the London streets. Then at last in December came news of the destruction of

Napoleon's armies in Russia, 'the most memorable reverse in history'. It was to

prove the beginning of the end of the French Emperor's power.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

A Year in the Life 1812

A Year in the Life 1812 The

Regent and his ministers clung doggedly to their policies of war and

repression. The only hopeful sign was the attendance of three of the Prince

Regent's brothers at a meeting held in May 'to consider the distressed state of

the labouring poor'. All that resulted, however, was the opening of a

subscription fund and the appointment of a committee.

The

Regent and his ministers clung doggedly to their policies of war and

repression. The only hopeful sign was the attendance of three of the Prince

Regent's brothers at a meeting held in May 'to consider the distressed state of

the labouring poor'. All that resulted, however, was the opening of a

subscription fund and the appointment of a committee.

0 Response to "British Great Artist John Constable - A Year in the Life 1812"

Post a Comment