Monet`s Garden

The

magnificent garden at Giverny took Monet almost 20 years to create, and

demanded all his artistic skills and imagination. For the rest of his life, it

provided endless subjects for his paintings.

Rarely

has an artist left behind such a complete record of his inspiration as did

Monet at Givemy. There, in the garden on which he lavished care and attention

for over 40 years, view after view conjures up his paintings: the lily pond,

the footbridge, the rose trellises. The garden was really an extension of his

art.

Givemy

lies some 40 miles north-west of Paris, in the rolling countryside of Normandy,

where two small tributaries, the Epte and the Ru, flow into the Seine. The

village nestles against wooded hills, overlooking a broad panorama of fields

dotted with lines of willow and poplar.

THE HOUSE AT GIVERNY

The

property which Monet rented for his large household in 1883 stood at the foot

of these hills a long, pink house with shutters. Two acres of orchard sloped

gently towards a narrow road, beyond which lush water meadows stretched down to

the river. The garden then was formal and uninspired. A broad, tree-lined

central walk led up to the house, flanked by two long flowerbeds edged with

clipped box hedges. At that time, there was little to excite the eye.

Wherever

he had lived before, Monet had always created gardens, but Giverny provided

scope for his most ambitious plans. It was late spring when the family moved

in. Monet immediately reorganized the kitchen garden to ensure a supply of

vegetables, then set to work on the house and flower garden. Trellises were

erected against the house to support clematis, climbing roses and Virginia

creeper. He chose the same shade of green to paint the shutters, doors and

porch of the house as he would later use for the arches and trellises in the

garden and for the Japanese bridge.

The

fruit trees in the orchard were uprooted and replaced with lawns, shaded by

ornamental cherries and japonicas and edged with a brilliant profusion of

flowering plants. New flower beds were dug, intersected by neat gravel paths in

straight lines and rectangles, which soon disappeared under the dense carpet of

flowers.

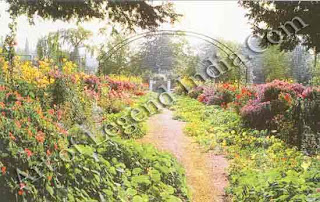

The

clipped box hedges were removed and the spruce and cypress trees lining the

central walk were cut down only two yews were left. By the 1890s a series of

curving arches spanned the walk, draped with climbing roses and clematis.

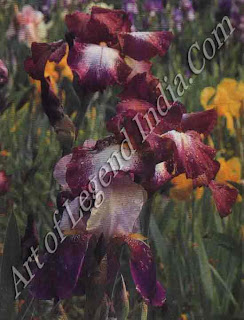

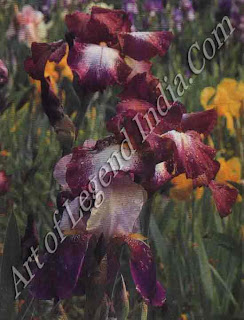

Masses of irises, poppies, asters, pansies and peonies bordered the walk

beneath the arches, while trailing nasturtiums spread over the path.

Monet

had approached the garden much as he would a canvas, using the same principles

that governed his palette. Flowers with light, bright blooms were planted in

clumps of contrasting colours, set off against green foliage no coloured or

variegated leaves were used. Monet avoided flowers with large blossoms,

preferring festoons of small-headed flowers clustering together to produce a

mass of colour.

FLOWERS FOR ALL SEASONS

In the

early spring, yellow jasmine and Christmas roses gave way to crocuses,

narcissi, tulips, azaleas, rhododendrons and flowering cherries, with dense

carpets of forget-me-nots. Later peonies, poppies and banks of irises would

appear with clematis and climbing roses clambering round trellis and arch. At

the height of summer the garden was a blaze of saffron, vermilion and blue

aubrietia covered the ground, while geraniums, daisies, zinnias, marigolds,

lilies, pinks and cannas flowered in abundance.

Monet's

garden included several hundred varieties of native and imported plants and up

to the end of his life the artist took delight in adding to his collection the

rare tree peonies in the water garden, for instance, and bulbs of lilies quite

unknown in France were given to him by his friends the Kurokis, who were

influential Japanese art collectors.

He also

encouraged his children to study botany, and in the early years at Giverny,

experiments in cross-breeding made by his son Michel and step-son Jean-Pierre

accidentally resulted in a new type of poppy, which they named Papaver Moneti.

'My

garden is a slow work, pursued by love,'

Monet

once said, 'and I do not deny that I am proud of it. I dug, planted, weeded

myself; in the evenings the children watered.' By 1890, Monet was wealthy

enough to buy the house and make still more improvements: in 1892 three

greenhouses were built and stocked with exotic orchids, begonias, figs and

tropical ferns. Now Monet took on a team of six gardeners who worked under his

close supervision. With the head gardener, he inspected the garden every day,

ordering all dead flowerheads to be removed.

THE WATER GARDEN

In 1893

Monet bought another plot of land across the road at the bottom of his garden,

intending to enlarge a tiny pond already there and to create a water garden. To

do this, it was necessary to divert the River Ru.

In 1893

Monet bought another plot of land across the road at the bottom of his garden,

intending to enlarge a tiny pond already there and to create a water garden. To

do this, it was necessary to divert the River Ru.

Monet

was not liked by the villagers, and they bitterly resented his plan. Monet

himself was judged to be aloof, and his family seemed to have no clear-cut

social status. The villagers had already claimed compensation for alleged

damage to their fields, through which the Monet family frequently trekked to

where their boats were moored.

Now

Monet's plans for a pond stocked with rare plants met with suspicion. The

women, who I washed their linen in the Ru, claimed it would be a health hazard.

And local peasants feared that their cows would be poisoned by drinking river

water 'contaminated' by strange plants. Finally, with many conditions,

permission was granted.

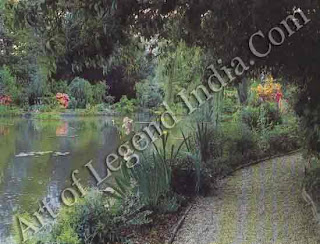

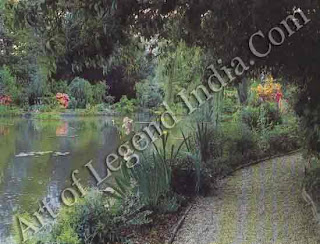

The

mood and atmosphere of the water garden was very different from the exuberance

of the flower garden. Here all was cool and tranquil. The pool was strewn with

exotic varieties of waterlily white, yellow, mauve and rose with clumps of

bamboo, weeping willows, irises and tamarisk smothering the banks. Monet added

the Japanese footbridge, a simple wooden arch with no supporting piers, painted

in his favourite brilliant green. To this, some years later, trellises were

added to support masses of wisteria.

The

mood and atmosphere of the water garden was very different from the exuberance

of the flower garden. Here all was cool and tranquil. The pool was strewn with

exotic varieties of waterlily white, yellow, mauve and rose with clumps of

bamboo, weeping willows, irises and tamarisk smothering the banks. Monet added

the Japanese footbridge, a simple wooden arch with no supporting piers, painted

in his favourite brilliant green. To this, some years later, trellises were

added to support masses of wisteria.

In 1901

Monet received permission to extend the pond further, since the size and shape

had become too restricting to him as he painted it more and more. By deepening

the curve and extending its length, he achieved a greater sense of space,

creating marvelous vistas from all round the pond. More species of lilies were

introduced and soon it was the sole task of a gardener to care for the pool,

for which he used a small boat permanently moored at the edge.

Just as

his flower garden had gradually become a recurrent theme of his painting, so

the waterlily pond and footbridge had begun to absorb Monet. As he grew older

he turned almost exclusively to his garden for ideas and right up to the very

end of his life he remained fascinated by the pool, with its beautiful,

shimmering reflections.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

In 1893

Monet bought another plot of land across the road at the bottom of his garden,

intending to enlarge a tiny pond already there and to create a water garden. To

do this, it was necessary to divert the River Ru.

In 1893

Monet bought another plot of land across the road at the bottom of his garden,

intending to enlarge a tiny pond already there and to create a water garden. To

do this, it was necessary to divert the River Ru.  The

mood and atmosphere of the water garden was very different from the exuberance

of the flower garden. Here all was cool and tranquil. The pool was strewn with

exotic varieties of waterlily white, yellow, mauve and rose with clumps of

bamboo, weeping willows, irises and tamarisk smothering the banks. Monet added

the Japanese footbridge, a simple wooden arch with no supporting piers, painted

in his favourite brilliant green. To this, some years later, trellises were

added to support masses of wisteria.

The

mood and atmosphere of the water garden was very different from the exuberance

of the flower garden. Here all was cool and tranquil. The pool was strewn with

exotic varieties of waterlily white, yellow, mauve and rose with clumps of

bamboo, weeping willows, irises and tamarisk smothering the banks. Monet added

the Japanese footbridge, a simple wooden arch with no supporting piers, painted

in his favourite brilliant green. To this, some years later, trellises were

added to support masses of wisteria.

0 Response to "Frenchish Great Artist Claude Monet - Monet`s Garden "

Post a Comment