German

Great Artist - Hans Holbein Life

German

Great Artist - Hans Holbein Life

The son

of a successful German artist, Hans Holbein worked in Switzerland before the

religious turmoil of the Reformation caused him to leave for England in search

of work. His first stay in London was spent among the circle of the great

scholar and statesman Sir Thomas More. After a period back in Switzerland with

his wife and family, Holbein returned to England, where he remained based until

his death from the plague.

Holbein's

phenomenal skill particularly at portrait painting was exploited by Henry VIII's

secretary, Thomas Cromwell, who drew him into the king's employ. Soon, Holbein

became Henry VIII's chief image-maker. Though little is known about his

character, Holbein seems to have been a cultivated but cold man, who could

switch his allegiance from More to Cromwell the man who ordered More's untimely

death.

A German at the English Court

Hans

Holbein moved to London permanently from his native Germany in 1532. His work

soon found favour at court and he was appointed King's Painter. Holbein died in

1543 of the plague.

Very

little is known about the life of Hans Holbein the Younger. Only a few dated

documents and Holbein's works themselves - including some enigmatic selfportraits

provide us with clues to the personality of the man who became King Henry Vu's

favourite painter.

Very

little is known about the life of Hans Holbein the Younger. Only a few dated

documents and Holbein's works themselves - including some enigmatic selfportraits

provide us with clues to the personality of the man who became King Henry Vu's

favourite painter.

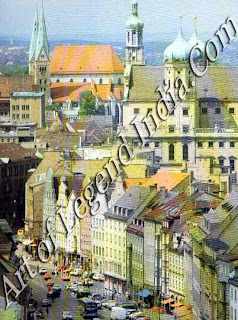

Holbein

was born in 1497/8 in Augsburg in Southern Germany. His father, Hans Holbein

the Elder, was a gifted painter and had already carved quite a reputation for

himself. Together with his elder brother, Ambrosius, the young Holbein trained

for a while in his father's studio, and in 1514 the two boys were sent to Basel

in Switzerland to serve their apprenticeships with the painter Hans Herbster.

In

Basel, Holbein also worked for the publisher, Froben, producing book illustrations

and a set of marginal drawings for Desiderius Erasmus's book Praise of Folly.

This very important commission put him in touch with Basel's humanist circle,

of which the scholar Erasmus was the leading light.

THE HUMANISTS

The

humanists placed paramount importance on the intellectual pursuits, potential

and wellbeing of mankind. Whereas medieval Christianity had taught the

insignificance of man's earthly existence, the humanists believed in the value

of human endeavours. They found the basis for their ideas in the literature and

philosophy of the ancient Greeks and Romans, where the virtues of liberality,

eloquence and wisdom were especially prized. Holbein seems to have gradually

formed close friendships with some of the northern humanists, particularly

Erasmus. Early on in his career his own humanistic interests were reflected in

the sophisticated classical details he introduced into his designs and

decorative schemes.

The

humanists placed paramount importance on the intellectual pursuits, potential

and wellbeing of mankind. Whereas medieval Christianity had taught the

insignificance of man's earthly existence, the humanists believed in the value

of human endeavours. They found the basis for their ideas in the literature and

philosophy of the ancient Greeks and Romans, where the virtues of liberality,

eloquence and wisdom were especially prized. Holbein seems to have gradually

formed close friendships with some of the northern humanists, particularly

Erasmus. Early on in his career his own humanistic interests were reflected in

the sophisticated classical details he introduced into his designs and

decorative schemes.

In

1517, and again in 1519, Holbein travelled to Lucerne, Switzerland, where he

decorated the house of the town's chief magistrate in a splendid illusionistic

style. At some point, probably in 1518, Holbein made a short trip to Italy

where the work of the Renaissance painters Andrea Mantegna and Leonardo da

Vinci made a profound impression on him. Once back in Basel, he soon showed Himself

to be a painter of great talent. He was extremely prolific, too, turning out

portraits, altarpieces and designs for stained glass, as well as a series of

huge frescoes.

Key Dates

C.1487 born in Augsburg,

southern Germany

1519 marries Elsbeth Binsenstock

1526 first visit to England;

introduction to Sir Thomas More

1528 returns to Basel

1533 paints The Ambassadors

1534 Henry VIII becomes Supreme

Head of the Church; Thomas More imprisoned; Holbein paints Thomas Cromwell

1537 appointed King's Painter

1543 dies of the plague in London

In 1519

Holbein joined the painters' guild and rapidly achieved the status of chamber

master. At this time he married Elsbeth Binsenstock, the widow of a tanner, who

already had one son. In time they had two sons of their own, who became

goldsmiths, and two daughters. It is assumed that He also had a mistress, a

certain Magdalena Offenburg, whom he painted in the appropriate guise of Lais the

mistress of the legendary Greek painter, Apelles. Magdalena probably also

modeled somewhat less appropriately for the Virgin in The Meyer Madonna.

In an

astonishingly short time Holbein had become the foremost artist of the northern

humanist movement. Among his finest works of this period are the three

portraits he painted of Erasmus and a series of anti-clerical woodcuts

illustrating the Dance of Death. In 1524 he visited France and expanded his

artistic horizons. But two years later the violent impact of the Reformation

brought religious painting in Basel to an abrupt halt and he was forced to seek

prestigious commissions elsewhere.

INTRODUCTION TO THOMAS MORE

Armed

with a letter of introduction from Erasmus to none other than Sir Thomas More

and Arch-bishop Warham, Holbein left for England 'to pick up some angels'

(coins), as Erasmus put it. He was welcomed by more in London and it is

believed that he stayed at his Chelsea house for the remainder of his visit.

Henry VIII had not yet begun his great program me of art patronage and so

Holbein did not work for the Crown at this time, but he probably met the king,

who was then in the habit of rowing down the Thames in his barge and calling on

his close friend More without warning. More was then approaching the height of

his political influence: the king relied on him both for company and advice,

and he was soon to be made Lord Chancellor.

Thus,

at a single bound, Holbein vaulted into the centre of political and

intellectual life in England. He exploited his opportunity to the hilt. His

sitters, all drawn from More's circle, included the king's astronomer and the

Archbishop, who had him painted in the same pose as Erasmus. The finest

portrait of this period, and perhaps of all Holbein's English output, was that

of more himself, conveying the man's aura of power as well as the sensitivity

of his intellect. Still more impressive perhaps would have been his group

portrait of the More family, but it has since been destroyed by fire.

In

1528, Holbein returned to Basel; he had only been granted a two-year leave of

absence and a longer stay would have cost him his citizenship. Also, the

Council had work for him. He bought two adjoining houses overlooking the Rhine

and settled down to paint frescoes for the Town Hall. During this period he

painted a sympathetic and intimate portrait of his wife and two of their children.

A RETURN TO LONDON

Meanwhile,

the situation in Basel was rapidly worsening. The Lutheran faction was at its

most extreme: Erasmus was forced to flee and iconoclasts destroyed nearly all

the city's religious paintings in a single day. Holbein obtained some minor

commissions decorating a tower clock in the city and designing patterns for

goldsmiths, jewelers and glassmakers; he even made some costume designs. But

the atmosphere was highly unfavorable to art of all sorts, and Holbein although

he supported the principles of the Reformation decided to return to London.

He

arrived late in 1532 to discover that events were moving very fast there too.

Archbishop Warham had died and Thomas More, having refused to endorse the

king's marriage to Anne Boleyn, had petitioned to resign the chancellorship. He

was now trying to live in Unobtrusive privacy and Holbein was obliged to turn

to another source of patronage. This he found among the German merchants at the

Steelyard, which was the London trading office of the Hanseatic League. At this

time he painted a magnificent full-length double portrait The Ambassadors, and

the virtuoso George Gisze, both designed to attract the attention of Tudor

court.

The

status of his patrons rose quickly. By 1534 he was painting the king's

secretary, Thomas Cromwell. In this same year more refused to swear the Oath of

Supremacy, declaring that 'no parliament could make a law that God should not

be God'. The king, who was now Supreme Head of the Church of England, had him

cruelly Imprisoned in the Tower, where he languished for another year while the

Crown's agents, directed by Cromwell, prepared their case against him.

Though

Cromwell was repulsive in appearance and character, qualities which are not

shirked in Holbein's portrait, he was the most important patron Holbein could

have acquired. During the next five years he not only filled the royal coffers

with monastic gold, but orchestrated the most lavish propaganda campaign in the

arts ever undertaken for the benefit of the Crown. One of the first jobs he

gave Holbein was to design a woodcut for the title page of the Coverdale Bible,

the first complete edition of the Bible in English. This showed Henry VIII

delivering the Word to the bishops.

Though

Cromwell was repulsive in appearance and character, qualities which are not

shirked in Holbein's portrait, he was the most important patron Holbein could

have acquired. During the next five years he not only filled the royal coffers

with monastic gold, but orchestrated the most lavish propaganda campaign in the

arts ever undertaken for the benefit of the Crown. One of the first jobs he

gave Holbein was to design a woodcut for the title page of the Coverdale Bible,

the first complete edition of the Bible in English. This showed Henry VIII

delivering the Word to the bishops.

In July

1535 Thomas More was executed and in the following year Anne Boleyn was the

first of Henry VIII's wives to lose her head. Holbein was now on the royal

payroll, and in 1537 he was appointed the King's Painter. For an annual income

of about £30, he performed a great variety of commissions for his royal master from

the design of his state robes to that of his book bindings. But he was chiefly

valued for being 'very excellent in making Physiognomies'. By this time, the

King had banned all religious painting.

Though

he was a genius as a painter, as a man Holbein seems to have been shrewd,

ambitious, ruthless and quite unscrupulous. Admittedly, the turbulent and

bloody politics of those days made compromise and sudden switches of loyalty a

virtual necessity for anyone close to the throne, even artists. But for all

that, it is difficult not to be surprised by someone who was able to sell his

talent to Cromwell, the man responsible for the death of more, his onetime

friend, patron, host and sponsor.

Though

he was a genius as a painter, as a man Holbein seems to have been shrewd,

ambitious, ruthless and quite unscrupulous. Admittedly, the turbulent and

bloody politics of those days made compromise and sudden switches of loyalty a

virtual necessity for anyone close to the throne, even artists. But for all

that, it is difficult not to be surprised by someone who was able to sell his

talent to Cromwell, the man responsible for the death of more, his onetime

friend, patron, host and sponsor.

A rare

insight into Holbein's character (or his reputed character) comes from an

anecdote told by The Flemish artist and art historian Karel van Mander. The

story goes that Holbein was painting a portrait of a lady for King Henry, when

a nobleman appeared in the room unannounced. The artist was so angered by the

interruption that he flung the offending intruder downstairs then hurried to

offer his apologies to the king.

PAINTING THE KING

In the

year 1537, Holbein was given his most momentous task when he was asked to paint

a commemorative group portrait of Henry VIII, his new Queen, Jane Seymour, and

the king's parents Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, which was to adorn the wall

of the Privy Chamber above the throne itself. In the event, Jane Seymour died

before the fresco was completed, having given birth to Henry's only and long

awaited son. 1537 was in every respect a year of shattering triumph for the

Tudor dynasty. Henry managed decisively to crush the most serious rebellion of

his reign, the so-called Pilgrimage of Grace, and showed the Pope to be

powerless to challenge his position as Supreme Head, next to Christ, of the

Church of England. The great fresco was therefore conceived as a celebration of

victory, peace and dynastic unity. Holbein had the job of enshrining in paint

the official Tudor view of the immediate past.

We can

only guess at the visual effect of his fresco, though every contemporary

reference testifies to its awesome power. For in 1698 the negligence of a

chamber maid caused the palace of Whitehall to be burnt to the ground.

Having

completed the Whitehall wall painting, Holbein was sent abroad with the

delicate task of painting likenesses of Henry's possible future wives. He

visited Brussels where he painted a portrait of the delightful Christina of

Denmark, which 'singularly pleased the king' and put him in a fine humour.

However, political negotiations broke down, and Henry never married her. For a

similar reason Holbein also painted a bland but pretty portrait of Anne of

Cleves, whom the King decided to marry (though he later described her as 'the

Flanders Mare').

In

September 1538 Holbein returned once more to Basel and his family. A banquet

was held in his honour and the city offered him a pension and other privileges

in the hope of tempting him to stay permanently. But he did not linger. Though

he was never naturalized, London had become his home as well as the centre of

his career.

In

September 1538 Holbein returned once more to Basel and his family. A banquet

was held in his honour and the city offered him a pension and other privileges

in the hope of tempting him to stay permanently. But he did not linger. Though

he was never naturalized, London had become his home as well as the centre of

his career.

In his

last years, Holbein painted less for the king, but there is no evidence that he

fell out of favour. Indeed, his last, unfinished work was a large painting of

Henry VIII granting the charter to the Barber-Surgeons' company. He also

continued to work for the Crown by travelling abroad on diplomatic missions

about which little are known.

DEATH FROM THE PLAGUE

Holbein's

life was cut short by the plague which raged through London in 1543. The will

he made in that year reveals that he was a resident in the parish of St Andrew

Undershaft in the City of London, and that he left two illegitimate 'chylder which

be at nurse'. But despite Holbein's illustrious career, his will contains no

mention of any property: only small items such as clothing and a horse. In fact

he left several debts. But the debt which English art owes to the foreigner

from Germany is far greater: he influenced the direction of English art for

centuries to come.

Writer- A Marshall Cavendish

Very

little is known about the life of Hans Holbein the Younger. Only a few dated

documents and Holbein's works themselves - including some enigmatic selfportraits

provide us with clues to the personality of the man who became King Henry Vu's

favourite painter.

Very

little is known about the life of Hans Holbein the Younger. Only a few dated

documents and Holbein's works themselves - including some enigmatic selfportraits

provide us with clues to the personality of the man who became King Henry Vu's

favourite painter.  The

humanists placed paramount importance on the intellectual pursuits, potential

and wellbeing of mankind. Whereas medieval Christianity had taught the

insignificance of man's earthly existence, the humanists believed in the value

of human endeavours. They found the basis for their ideas in the literature and

philosophy of the ancient Greeks and Romans, where the virtues of liberality,

eloquence and wisdom were especially prized. Holbein seems to have gradually

formed close friendships with some of the northern humanists, particularly

Erasmus. Early on in his career his own humanistic interests were reflected in

the sophisticated classical details he introduced into his designs and

decorative schemes.

The

humanists placed paramount importance on the intellectual pursuits, potential

and wellbeing of mankind. Whereas medieval Christianity had taught the

insignificance of man's earthly existence, the humanists believed in the value

of human endeavours. They found the basis for their ideas in the literature and

philosophy of the ancient Greeks and Romans, where the virtues of liberality,

eloquence and wisdom were especially prized. Holbein seems to have gradually

formed close friendships with some of the northern humanists, particularly

Erasmus. Early on in his career his own humanistic interests were reflected in

the sophisticated classical details he introduced into his designs and

decorative schemes.  Though

Cromwell was repulsive in appearance and character, qualities which are not

shirked in Holbein's portrait, he was the most important patron Holbein could

have acquired. During the next five years he not only filled the royal coffers

with monastic gold, but orchestrated the most lavish propaganda campaign in the

arts ever undertaken for the benefit of the Crown. One of the first jobs he

gave Holbein was to design a woodcut for the title page of the Coverdale Bible,

the first complete edition of the Bible in English. This showed Henry VIII

delivering the Word to the bishops.

Though

Cromwell was repulsive in appearance and character, qualities which are not

shirked in Holbein's portrait, he was the most important patron Holbein could

have acquired. During the next five years he not only filled the royal coffers

with monastic gold, but orchestrated the most lavish propaganda campaign in the

arts ever undertaken for the benefit of the Crown. One of the first jobs he

gave Holbein was to design a woodcut for the title page of the Coverdale Bible,

the first complete edition of the Bible in English. This showed Henry VIII

delivering the Word to the bishops.  Though

he was a genius as a painter, as a man Holbein seems to have been shrewd,

ambitious, ruthless and quite unscrupulous. Admittedly, the turbulent and

bloody politics of those days made compromise and sudden switches of loyalty a

virtual necessity for anyone close to the throne, even artists. But for all

that, it is difficult not to be surprised by someone who was able to sell his

talent to Cromwell, the man responsible for the death of more, his onetime

friend, patron, host and sponsor.

Though

he was a genius as a painter, as a man Holbein seems to have been shrewd,

ambitious, ruthless and quite unscrupulous. Admittedly, the turbulent and

bloody politics of those days made compromise and sudden switches of loyalty a

virtual necessity for anyone close to the throne, even artists. But for all

that, it is difficult not to be surprised by someone who was able to sell his

talent to Cromwell, the man responsible for the death of more, his onetime

friend, patron, host and sponsor. In

September 1538 Holbein returned once more to Basel and his family. A banquet

was held in his honour and the city offered him a pension and other privileges

in the hope of tempting him to stay permanently. But he did not linger. Though

he was never naturalized, London had become his home as well as the centre of

his career.

In

September 1538 Holbein returned once more to Basel and his family. A banquet

was held in his honour and the city offered him a pension and other privileges

in the hope of tempting him to stay permanently. But he did not linger. Though

he was never naturalized, London had become his home as well as the centre of

his career.

0 Response to "German Great Artist - Hans Holbein Life"

Post a Comment