French Great Artist Paul Gauguin -The Lure of Tahiti

Posted by

Art Of Legend India [dot] Com

On

4:57 AM

The

jewel of the vast Pacific Ocean, Tahiti was famed as a paradise

on

earth long before Gauguin visited its shores. European sailors

had

savoured the island's pleasures since the days of Captain Cook.

In

1890, Gauguin wrote to a friend 'I am leaving for Tahiti, where I shall hope to

end my days.' His decision was influenced partly by the fact that Tahiti was as

far away from Paris as it was possible to get,, but also by the stream of

enthusiastic reports reaching Europe from travellers who had visited the

hauntingly beautiful island.

The

unspoiled paradise of Gauguin's dreams, however, had vanished long before he

reached the capital Papeete in 1891. There were church bells and gendarmes

awaiting him as well as lovely garlanded maidens, stolid French housewives

preparing old-fashioned country meals as well as carefree islanders living free

off taro, yam and breadfruit. The 'mysterious beings' he had imagined before

his arrival managed to consume 45,000 gallons of island rum and 65,000 gallons

of imported claret each year.

But the

place itself was too lovely and the people too resilient for either to be

spoiled completely. Communications were so bad that Europeanized Papeete could

not make much of an impression on the rest of the island. Even today the only

real road follows the coast, and in the 1890s, the interior was largely

trackless. In rural districts, people lived much as they always had, by fishing

or small-scale farming.

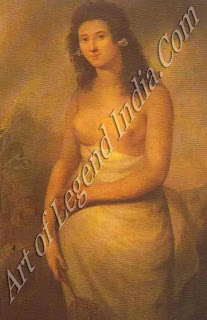

Tahiti

had a mesmerizing effect on Gauguin, as it had on other European visitors since

its discovery by Britain's Captain Samuel Wallis in 1767. An extinct volcano

lost in the immensity of the South Pacific, its lush, green slopes rise to a

7,349-foot peak, high above a shoreline ringed by coral reefs that enclose

lagoons swarming with fish. But it was the island's inhabitants who made the

greatest impression on the early explorers. They were handsome and easy-going

people, Polynesians whose ancestors had settled around 4,000 years ago. In

Tahiti they had evolved a lifestyle that Westerners, accustomed to the drudgery

g. of their own societies, saw as a kind of paradise. The climate, though a

little damp, was balmy and reasonably cool by tropical standards. Fish and

shellfish, breadfruit and bananas seemed to be had for the asking, without

labour. There was little need for clothing. And as Wallis and his crew

discovered to the captain's horror and the men's delight the languid young

women of the island were only too willing to exchange their favors’ for some

trifling gift. Iron nails were the favoured currency: by the time Wallis sailed

for home after a F month's sojourn, the fixed bayonets of his Royal Marines

were barely enough to stop his men prising out every iron fastening in the ship.

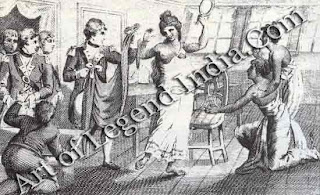

While

Wallis, a tough but unimaginative officer, was preparing his report for the

Admiralty, an explorer with a more philosophical turn of mind 5 was making his

landfall on Tahiti. Louis Antoine de Bougainville was not only a soldier and a

navigator. He was also steeped in the new ideas sweeping 18th-century Europe.

And in Tahiti he found a reality to match philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau's

ideal of the noble savage of man at peace with nature.

Bougainville

and his crew were welcomed as Wallis had been. 'They pressed us to choose a

woman and to come on shore with her,' he wrote, 'and their gestures, which were

unmistakably clear, denoted in what manner we should form an acquaintance with

her.' His naturalist, Philibert Commerson, enthused about 'natural man, who is

born essentially good, free of every prejudice, and who follows, without

defiance and without remorse, the gentle impulses of instinct not yet corrupted

by reason.'

Commerson's

was a notion that endured until Gauguin's time and after. But although it

contained a germ of truth, it was largely illusion born out of wishful

thinking. For life on Tahiti was no idyll. The islanders did not use the

leisure time granted by their comfortable environment to live the kind of

rapturous, untrammelled existence dreamed of by European philosophers. Instead,

with or without assistance from 'the gentle impulses of instinct', they had

created a fierce warrior society that indulged in slavery and human sacrifice.

Nor did

the blithe promiscuity of many young Tahitian women mean that they were

devotees of free love. In fact, the Tahitians had a complex set of rules for

sexual behavior inside and outside marriage, which even today anthropologists

have not fully elucidated. a European who made an enthusiastic grab for the

wrong woman could and often did pay for it with his life.

Nevertheless,

the island never lost its seductive fascination. Captain James Cook, who

visited it in 1769, was reduced to holding Tahitian chiefs hostage to obtain

the return of deserters from his ship and Cook was a well-loved leader. In

1789, the contrast between Tahitian life and Royal Naval discipline was enough

to provoke the celebrated mutiny on HMS Bounty. Regardless of its flaws,

paradise Tahiti-style was better than life on ship.

But the

coming of the Europeans was itself enough to put an end to the old way of life.

The newcomers brought syphilis, a poor return for the island women's

affections. They brought measles and smallpox and a host of other diseases to

which the Polynesians had little or no resistance. They brought rum. And

unscrupulous and well-armed Europeans took sides for their own advantage in the

island's internal quarrels, which were bloody enough already without their

help.

The

results were quite devastating. According to some estimates, Tahiti's 402

square miles supported as many as 150,000 people before the Europeans came. By

the end of the century the population had crashed to 15,000; by 1830 it had

fallen to 8,000.

Missionaries

did their own kind of damage. Their first settlement was established in 1797,

and although they did their best to protect their flocks from the ravages of

drink and disease, they eventually succeeded in undermining the local

traditions that any society needs in order to keep its self-respect. The

islanders were told of the evils of nakedness and fornication, and introduced

to the doctrinal distinctions between Calvinists and Catholics and all the

other Christian sects.

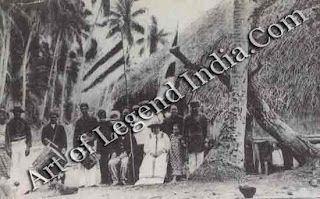

Outright

colonization followed. Anglo-French rivalry ended with a half-hearted French

Protectorate established in 1843; the last Tahitian king with any pretence at

independence abdicated in 1880 and in that year the island became a full French

colony.

Tahiti's

fate could have been much worse. By 19th-century standards, the colonial

administration was efficient and humane. Outside the capital of Papeete, French

was seldom spoken, and disputes were more likely to be settled by ancient

tribal law than official regulations. Christianity had successfully driven out

the old pagan worship, and even the names of ancient gods had been forgotten;

but although Tahitians had become regular church-goers, traditional festivals

of song and dance had survived.

A cold

observer would see that imported, factory-woven cloth had replaced native

products, that there was much hymn-singing, that bit by bit the population was

beginning to drift towards the modestly bright lights of Papeete. But a painter

would see what his mind wanted to see. Paradise, like beauty, was in the eye of

the beholder.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "French Great Artist Paul Gauguin -The Lure of Tahiti"

Post a Comment