The Painter

An

inscription of the second century B.C. in the Ramgarh (Jogimara) cave, in early

characters, is the earliest to refer to a painter. It mentions a rupataka and

his sweetheart an adept in dance. As art permeated life in ancient India, every

young man and woman of taste had a knowledge of art, dance and music as

essential factors of literary aesthetic education. The non-professional

artists, with enough knowledge adequately to appreciate art trends in the

country, were in abundance and judged the art of the professionals.

The

fine arts were cultivated as a pastime, vinodasthana; and painting, being an

easier medium than modelling and sculpture, was probably more readily

preferred. The Kamasutra mentions painting as one of the several arts cultivated

by a nagaraka, a gentleman of taste. His chamber should have a lute (vina)

hanging by a peg on the wall, a painting board (chitraphalaka), a casket full

of brushes (vartikasamudgaka), a beautiful illuminated manuscript and

sweet-smelling flower garlands. The chitrakara was a professional artist of

eminence. Inferior craftsmen were known as dindins. The Uttararamacharita

refers to a chitrakara named Arjuna who had painted the murals illustrating the

life of Rama in the palace. The architects, artists and painters who had

decorated the royal palace on the eve of the marriage of princesss Rajyasri

were shown great respect as recorded in the Harshacharita. This shows the high

esteem in which they were held. When they were commissioned to do some work, they

were honoured before they started on it. From the Kathasaritsagara, we learn

that a painter enjoyed ten villages as a gift from the king. The chitrakaras,

along with sculptors, jewellers, goldsmiths, wood-carvers, metal crafts-men and

others, had an allocation of seats in the assembly of poets and scholars

convened in the royal court, as described by Rajasekhara in his Kavyamimamsa.

Distinguished

masters were specially honoured and invited to give their opinion on the

aesthetic value of works of art. These chitravidyopadhyayas were well-versed in

several branches of art. Encyclopedic knowledge of masters in architecture,

sculpture and painting and other allied branches is gathered from several

inscriptions. One of the best known among these is from Pattadakal, where the

silpi from the southern region, specially invited by king Vikramaditya to build

the Virupaksha temple, describes himself as an adept in every branch of art. A

scribe, who was a contemporary of the Western Chalukya king, Vikramaditya VI, boasts

of his skill in arranging beautiful letters in artistic form, entwining into

them shapes of birds and animals. The queen who enters the chitrasala, as

described in the Malavikagnimitra, intently gazes at the newly-painted

pictures, representing the harem with its retinue; and this being the work of a

master, and naturally compels her admiration. According to the

Vidhasalabhanjika, the queen's nephew, occasionally dressed in feminine attire,

is mistaken by painters (chitrakaras) to be a girl and represented thus almost

life-like on the palace walls, causing the king to mistake him for a girl.

Royal courts were frequented by numerous chitrakaras, as we gather from several

references; and an interesting instance is that of a painter who prepared an

exceedingly beautiful picture of a princess to demonstrate his skill in the

royal court. The Kathasaritsagara mentions one Kumaradatta as a gifted painter

at the court of king Prithvirupa of Pratishthana. The same text mentions

another famous painter, Roladeva from Vidarbha. Sivasvamin, a respectable

chitracharya, and an adept in painting is described as the lover of a courtesan

in the Padataditaka. Painters frequently visited Vesavasas and had naive

companions in natas, nartakas and vitas, vesyas and kuttanis. This indicates

their social position, which was not very high, though their art was

appreciated at the highest level. The high ideal of vinodastluma for art

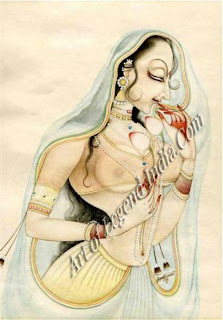

amongst the nagarakas was just the opposite in the case of the courtesan, who

also learned art, neither as a professional nor as an amateur, but as one to

brandish her proficiency in fine arts to attract suitors, and to flourish in

her profession, as Damodaragupta portrays in his Kuttanimata. The morals of the

silpi class of his time are the subject of Kshemendra's interesting lampoon.

Distinguished

masters were specially honoured and invited to give their opinion on the

aesthetic value of works of art. These chitravidyopadhyayas were well-versed in

several branches of art. Encyclopedic knowledge of masters in architecture,

sculpture and painting and other allied branches is gathered from several

inscriptions. One of the best known among these is from Pattadakal, where the

silpi from the southern region, specially invited by king Vikramaditya to build

the Virupaksha temple, describes himself as an adept in every branch of art. A

scribe, who was a contemporary of the Western Chalukya king, Vikramaditya VI, boasts

of his skill in arranging beautiful letters in artistic form, entwining into

them shapes of birds and animals. The queen who enters the chitrasala, as

described in the Malavikagnimitra, intently gazes at the newly-painted

pictures, representing the harem with its retinue; and this being the work of a

master, and naturally compels her admiration. According to the

Vidhasalabhanjika, the queen's nephew, occasionally dressed in feminine attire,

is mistaken by painters (chitrakaras) to be a girl and represented thus almost

life-like on the palace walls, causing the king to mistake him for a girl.

Royal courts were frequented by numerous chitrakaras, as we gather from several

references; and an interesting instance is that of a painter who prepared an

exceedingly beautiful picture of a princess to demonstrate his skill in the

royal court. The Kathasaritsagara mentions one Kumaradatta as a gifted painter

at the court of king Prithvirupa of Pratishthana. The same text mentions

another famous painter, Roladeva from Vidarbha. Sivasvamin, a respectable

chitracharya, and an adept in painting is described as the lover of a courtesan

in the Padataditaka. Painters frequently visited Vesavasas and had naive

companions in natas, nartakas and vitas, vesyas and kuttanis. This indicates

their social position, which was not very high, though their art was

appreciated at the highest level. The high ideal of vinodastluma for art

amongst the nagarakas was just the opposite in the case of the courtesan, who

also learned art, neither as a professional nor as an amateur, but as one to

brandish her proficiency in fine arts to attract suitors, and to flourish in

her profession, as Damodaragupta portrays in his Kuttanimata. The morals of the

silpi class of his time are the subject of Kshemendra's interesting lampoon.

The

proficient artist, with hastochchaya or a good hand in producing pictures,

still commanded respect for his distinction in his field. The dindins, inferior

artists of mediocre taste, were in contrast to the chitracharyas, reputed for

their hastochchaya. Usually employed to repair old pictures, carvings and

flags, the dindins very nearly ruined them; it is no wonder that the

Padataditaka considers them to be not very different from monkeys dindino hi

namaite nativiprakrishta vanarebhyah. They are notorious for ruining pictures

by touching them up and for darkening the original lustre of colours by dabbing

with their brushes, alekhyam atmalipibhir gamayanti nasam saudheshu

kurchalcamashimalam arpayanti.

Colours,

prepared by the artist himself, as they occurred to his taste, were carried

along with the brushes in boxes, satnudgakas, gourds, alabus, specially

prepared for the purpose. Paintings on cloth were carefully preserved in silken

covers, in which they were rolled and kept. A beautiful picture is given of the

painter at work in the Mrichchhakatika, surrounded by a large number of colour

pans, from which he would just take a little from each, to put it on the

canvas, yo narnaham tatrabhavatas charudattasya riddhyahoratram prayatnasiddair

uddamasurabhigandhibhir modakair eva asitabhyantarachatussalakadvara upavishto

mallakasataparivrita chitrakara ivangulibhis sprishtva sprishtvapanayami. The

artist was alert to recognise a good picture when he achieved it, and even while

painting would nod his head in joyous approbation.

This

special trait of the painter has been noted by Valmiki, Harshavardhana,

Sriharsha, Kshemendra, Hemachandra and others. Passages like vikshya yam bahu

dhuvan siro jaravataki vidhirakalpi silpirat from the Naishadhiyacharita (XIII,

12) or yayau vilolayan maulim rupatisayavismitah in the Brihatkathamanjari (IX,

1121), or siramsi chalitani vismayavasad dhruvam vedhaso vidhyaya lalanam

jagattrayalalamabhutainimam from the Ratnavali (Act II, 41) amply illustrate

this.

This

special trait of the painter has been noted by Valmiki, Harshavardhana,

Sriharsha, Kshemendra, Hemachandra and others. Passages like vikshya yam bahu

dhuvan siro jaravataki vidhirakalpi silpirat from the Naishadhiyacharita (XIII,

12) or yayau vilolayan maulim rupatisayavismitah in the Brihatkathamanjari (IX,

1121), or siramsi chalitani vismayavasad dhruvam vedhaso vidhyaya lalanam

jagattrayalalamabhutainimam from the Ratnavali (Act II, 41) amply illustrate

this.

This

did not, however, mean any pride or self-appreciation. Painters in ancient

India, as we know had the humility to invite and accept criticism. In fact, the

Tilakamanjari refers to connoisseurs invited to appraise pictures tadasya kuru kalasastrakusalasya

kausalikam and kumara asti kinchid darsanayogyarn atra chitra pate, udbhutotra

pate kopi dosho va natimatram pratibhati.

It was

always a great joy for the painter to fashion the pictures with his own hand,

and he tried and did his best. His experimental sketches were known as

hastalekhas. Such preliminary sketches are often mentioned in literature. The

term varnaka connotes a final hastalekha, comparable to the determinant sketch

mentioned by Ruskin.

Passages

in literature help us to understand various stages in painting a picture, such

as the preparation of the ground, the drawing of the sketches, technically

known as rekhapradana or chitrasutradana, almost measured out on the board,

filling with colours, modelling through the three modes of vartanas and so

forth. The final addition of touches to make the picture live is the chit

ronmilana or the infusing of life into it. A well-known maxim is based on this

chitronmilana. Kalidasa compares the charm of Parvati to a picture infused with

life by unmilana, unmilotam tulikayeva chitram (Kumarasanibhava, I, 32). This

is the final process of painting the eyes of the figure by the painter when all

the rest is complete. Even today, this is a living tradition amongst the

hereditary craftsmen in India and Ceylon, who observe this in a solemn

ceremony.

Several

references provide an interesting picture of the habits of artists. Kshemendra

calls them kalachoras, thieves of time, since they usually delay their work

though anxious to receive their wages in time. The artist, however, was ever

aware of the superiority of his art, and when an occasion required it, he could

rise equal to it and prove his worth. A special method was in vogue to

challenge other painters in royal courts. A renowned painter, approaching the

palace gate, would put up a flag aloft, with his challenge painted on it,

asking anyone who accepted the challenge to pull it down. This was the prelude

to a contest in the court, decision by the ruler, and honour to the victor.

The

Indian painter, like the sculptor, usually dedicated himself to his art. He

made it an offering to the divine spirit and personally obscured himself. The

result has been that most names of artists in India are lost in oblivion. In

the Saundaryalahari, Sankara mentions even silpa as pujavidhana or a path of

worship. How a picture is to be prepared in the orthodox mode is illustrated in

the Vishnudharmottara, that requires the painter to sit devoted, facing east,

and offer prayers before commencing his work.

The

Indian painter, like the sculptor, usually dedicated himself to his art. He

made it an offering to the divine spirit and personally obscured himself. The

result has been that most names of artists in India are lost in oblivion. In

the Saundaryalahari, Sankara mentions even silpa as pujavidhana or a path of

worship. How a picture is to be prepared in the orthodox mode is illustrated in

the Vishnudharmottara, that requires the painter to sit devoted, facing east,

and offer prayers before commencing his work.

The

picture is believed always to reflect the mental and physical state of the

chitrakara. The Visimudharmottara mentions anyachittata, or absentmindedness,

as one of the causes that ruin the formation of a good picture. A common belief

mentioned in the Viddhasalabhanjilca is that a picture generally reflects the

merits of the artist even as a literary work does those of the poet in its

excellence, evam etat, yato garishthagoshthishvapyevam, kila struyate yadrisas

chit rakaras tadrishe chit rakarmaruparekha, yadrishah kavis tadrise

kavabandhachchhaya. The same is repeated in the Kavyamimamsa-sa yatsvabhavah

kavistadrisarupam kavyam, yadrisakaras chitrakaras tadrisakaram asya chitramiti

prayaso vadah.

Writer - C.SIVARAMAMURTI

Distinguished

masters were specially honoured and invited to give their opinion on the

aesthetic value of works of art. These chitravidyopadhyayas were well-versed in

several branches of art. Encyclopedic knowledge of masters in architecture,

sculpture and painting and other allied branches is gathered from several

inscriptions. One of the best known among these is from Pattadakal, where the

silpi from the southern region, specially invited by king Vikramaditya to build

the Virupaksha temple, describes himself as an adept in every branch of art. A

scribe, who was a contemporary of the Western Chalukya king, Vikramaditya VI, boasts

of his skill in arranging beautiful letters in artistic form, entwining into

them shapes of birds and animals. The queen who enters the chitrasala, as

described in the Malavikagnimitra, intently gazes at the newly-painted

pictures, representing the harem with its retinue; and this being the work of a

master, and naturally compels her admiration. According to the

Vidhasalabhanjika, the queen's nephew, occasionally dressed in feminine attire,

is mistaken by painters (chitrakaras) to be a girl and represented thus almost

life-like on the palace walls, causing the king to mistake him for a girl.

Royal courts were frequented by numerous chitrakaras, as we gather from several

references; and an interesting instance is that of a painter who prepared an

exceedingly beautiful picture of a princess to demonstrate his skill in the

royal court. The Kathasaritsagara mentions one Kumaradatta as a gifted painter

at the court of king Prithvirupa of Pratishthana. The same text mentions

another famous painter, Roladeva from Vidarbha. Sivasvamin, a respectable

chitracharya, and an adept in painting is described as the lover of a courtesan

in the Padataditaka. Painters frequently visited Vesavasas and had naive

companions in natas, nartakas and vitas, vesyas and kuttanis. This indicates

their social position, which was not very high, though their art was

appreciated at the highest level. The high ideal of vinodastluma for art

amongst the nagarakas was just the opposite in the case of the courtesan, who

also learned art, neither as a professional nor as an amateur, but as one to

brandish her proficiency in fine arts to attract suitors, and to flourish in

her profession, as Damodaragupta portrays in his Kuttanimata. The morals of the

silpi class of his time are the subject of Kshemendra's interesting lampoon.

Distinguished

masters were specially honoured and invited to give their opinion on the

aesthetic value of works of art. These chitravidyopadhyayas were well-versed in

several branches of art. Encyclopedic knowledge of masters in architecture,

sculpture and painting and other allied branches is gathered from several

inscriptions. One of the best known among these is from Pattadakal, where the

silpi from the southern region, specially invited by king Vikramaditya to build

the Virupaksha temple, describes himself as an adept in every branch of art. A

scribe, who was a contemporary of the Western Chalukya king, Vikramaditya VI, boasts

of his skill in arranging beautiful letters in artistic form, entwining into

them shapes of birds and animals. The queen who enters the chitrasala, as

described in the Malavikagnimitra, intently gazes at the newly-painted

pictures, representing the harem with its retinue; and this being the work of a

master, and naturally compels her admiration. According to the

Vidhasalabhanjika, the queen's nephew, occasionally dressed in feminine attire,

is mistaken by painters (chitrakaras) to be a girl and represented thus almost

life-like on the palace walls, causing the king to mistake him for a girl.

Royal courts were frequented by numerous chitrakaras, as we gather from several

references; and an interesting instance is that of a painter who prepared an

exceedingly beautiful picture of a princess to demonstrate his skill in the

royal court. The Kathasaritsagara mentions one Kumaradatta as a gifted painter

at the court of king Prithvirupa of Pratishthana. The same text mentions

another famous painter, Roladeva from Vidarbha. Sivasvamin, a respectable

chitracharya, and an adept in painting is described as the lover of a courtesan

in the Padataditaka. Painters frequently visited Vesavasas and had naive

companions in natas, nartakas and vitas, vesyas and kuttanis. This indicates

their social position, which was not very high, though their art was

appreciated at the highest level. The high ideal of vinodastluma for art

amongst the nagarakas was just the opposite in the case of the courtesan, who

also learned art, neither as a professional nor as an amateur, but as one to

brandish her proficiency in fine arts to attract suitors, and to flourish in

her profession, as Damodaragupta portrays in his Kuttanimata. The morals of the

silpi class of his time are the subject of Kshemendra's interesting lampoon.  This

special trait of the painter has been noted by Valmiki, Harshavardhana,

Sriharsha, Kshemendra, Hemachandra and others. Passages like vikshya yam bahu

dhuvan siro jaravataki vidhirakalpi silpirat from the Naishadhiyacharita (XIII,

12) or yayau vilolayan maulim rupatisayavismitah in the Brihatkathamanjari (IX,

1121), or siramsi chalitani vismayavasad dhruvam vedhaso vidhyaya lalanam

jagattrayalalamabhutainimam from the Ratnavali (Act II, 41) amply illustrate

this.

This

special trait of the painter has been noted by Valmiki, Harshavardhana,

Sriharsha, Kshemendra, Hemachandra and others. Passages like vikshya yam bahu

dhuvan siro jaravataki vidhirakalpi silpirat from the Naishadhiyacharita (XIII,

12) or yayau vilolayan maulim rupatisayavismitah in the Brihatkathamanjari (IX,

1121), or siramsi chalitani vismayavasad dhruvam vedhaso vidhyaya lalanam

jagattrayalalamabhutainimam from the Ratnavali (Act II, 41) amply illustrate

this.  The

Indian painter, like the sculptor, usually dedicated himself to his art. He

made it an offering to the divine spirit and personally obscured himself. The

result has been that most names of artists in India are lost in oblivion. In

the Saundaryalahari, Sankara mentions even silpa as pujavidhana or a path of

worship. How a picture is to be prepared in the orthodox mode is illustrated in

the Vishnudharmottara, that requires the painter to sit devoted, facing east,

and offer prayers before commencing his work.

The

Indian painter, like the sculptor, usually dedicated himself to his art. He

made it an offering to the divine spirit and personally obscured himself. The

result has been that most names of artists in India are lost in oblivion. In

the Saundaryalahari, Sankara mentions even silpa as pujavidhana or a path of

worship. How a picture is to be prepared in the orthodox mode is illustrated in

the Vishnudharmottara, that requires the painter to sit devoted, facing east,

and offer prayers before commencing his work.

0 Response to "Indian Painting - The Painter"

Post a Comment