Roguish Humour

Roguish Humour

Through

patient effort, Miro evolved an art of beguiling freshness and spontaneity,

developing a highly personal language of signs and symbols and displaying his

savage delight in the absurd.

At the

beginning of the century, Barcelona, capital of Catalonia, was the cultural

centre of Spain. It was here that Miro discovered the works of the Post

Impressionists, the Fauves and the Cubists which helped to shape his early

style. But it was Catalonia's mountainous landscape where Miro's family came

from that was his greatest inspiration. In his early 'realist' paintings, he

recorded every detail of this landscape with scrupulous attention and devotion.

'What interests me above all', he wrote to a friend, 'are the tiles on the

roof, the calligraphy of a tree, leaf by leaf and branch by branch, blade of

grass by blade of grass.' While he was working on The Farm in 1921-22 a tribute

to his family house in Montroig he used to take clods of earth and grasses with

him in his suitcase when he travelled to Paris, so that the precise details

would not escape him.

But

there was also a strong element of fantasy in Miro's character, which attracted

him to the less realistic work of the early Romanesque painters who decorated

the old Catalonian chapels with frescoes of simple, brightly-coloured figures,

using distortion and a hieratic scale for symbolic or emotional effects. He

also admired the stocky painted plaster figures made by local artisans for

their lack of artistic pretension. Such things appealed to him for their naive

humour and honesty, and the tricks of distortion and of depicting important

things much larger were later assimilated into his own work.

In

Paris, Miro was encouraged to develop his imaginative faculties by the

Surrealist poets and artists that he met. Fascinated by their experiments with

summoning up the unconscious through states of hallucination, he would sit for

hours in his studio capturing the strange sensations and forms he experienced

when hallucinating himself through extreme hunger. The artistic freedom of this

method was vital to his creative development: from the early 1920s onwards,

Miro no longer used space and colour in a realistic way to depict everyday

objects, and the forms that appeared in his paintings became a personal

language of signs and symbols.

In

Paris, Miro was encouraged to develop his imaginative faculties by the

Surrealist poets and artists that he met. Fascinated by their experiments with

summoning up the unconscious through states of hallucination, he would sit for

hours in his studio capturing the strange sensations and forms he experienced

when hallucinating himself through extreme hunger. The artistic freedom of this

method was vital to his creative development: from the early 1920s onwards,

Miro no longer used space and colour in a realistic way to depict everyday

objects, and the forms that appeared in his paintings became a personal

language of signs and symbols.

SIMPLIFYING FORMS

Miro's

Catalan peasants became stick-like figures, for example, recognizable by their

attributes: Phrygian cap and a pipe perhaps or a wedge-shaped hunter's knife

and gun. Many of Miro's humorous figures look naive and unsophisticated, like

children's doodles, and he was deliberately trying to evolve an art that would

stimulate basic sensations of humour, fear, excitement and passion in the

spectator; to 'rediscover the religious and magic sense of things, which is

that of primitive peoples'. He developed his new figures by a process of

simplification, a stripping away of unnecessary details. 'Showing all the

details', he said, 'would deprive them of that imaginary life that enlarges everything.'

Miro's

Catalan peasants became stick-like figures, for example, recognizable by their

attributes: Phrygian cap and a pipe perhaps or a wedge-shaped hunter's knife

and gun. Many of Miro's humorous figures look naive and unsophisticated, like

children's doodles, and he was deliberately trying to evolve an art that would

stimulate basic sensations of humour, fear, excitement and passion in the

spectator; to 'rediscover the religious and magic sense of things, which is

that of primitive peoples'. He developed his new figures by a process of

simplification, a stripping away of unnecessary details. 'Showing all the

details', he said, 'would deprive them of that imaginary life that enlarges everything.'

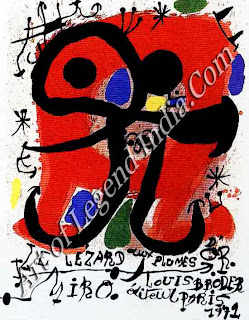

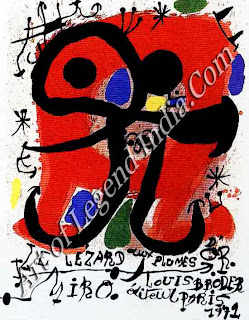

The

same figures Catalan peasants, women and birds, ladders, stars and strange

nocturnal creatures appear over and over again in his work. The ladder, for

example, was part of the familiar clutter around the Montroig farmhouse, but

gradually it became transformed in Miro's paintings into a symbol of escape,

often leading into a night sky as in Dog Barking at the Moon (left). Woman was

usually portrayed as Mother Earth, 'to whom Mini always offers his devotion': a

symbol of fecundity as she is often shown in primitive ethnic sculptures. And

the bird, like the ladder, represents the freedom of the spirit and an escape

from mundane everyday reality. Other shapes and hieroglyphs are not so easy to

interpret, sometimes being there just to satisfy Miro's sense of balanced

composition, but they all contribute to the haunting fascination of his work.

'It is signs that have no precise meaning that provoke a magic sense', he

believed. Sometimes, these eccentric symbols are reminiscent of Chinese or

Japanese written characters, and Miro is paintings become a playful form of

calligraphy.

Miro

felt free to distort and rearrange as his imagination dictated, and to place

anatomical forms arms, heads, breasts, hands and feet and other signs in

comical juxtapositions. Some of his paintings, like Harlequin's Carnival, are

very light-hearted and humorous, as if Miro took a childish delight in

arranging his toys, but his forms have also been described as 'torture

instruments'.

Miro

felt free to distort and rearrange as his imagination dictated, and to place

anatomical forms arms, heads, breasts, hands and feet and other signs in

comical juxtapositions. Some of his paintings, like Harlequin's Carnival, are

very light-hearted and humorous, as if Miro took a childish delight in

arranging his toys, but his forms have also been described as 'torture

instruments'.

During

the 1930s and the war years, and particularly in the Barcelona Suite of

lithographs, Miro created a nightmare world of vicious grossly distorted

monsters. His women sprouted ugly spikes of hair, claw-like nails and their

gaping mouths are filled with jagged fangs. Both his males and females, often

attacking each other, were given enormous sexual organs. Distressed and

disturbed by political events, Miro was showing man in all his bestiality and

cruelty, indulging his most destructive instinctual drives and the coarser

aspect of his humour.

Miro

had no respect for conventional aesthetic standards. Apart from the content of

his work, he often chose to use the meanest of materials, making collages and

sculptures out of cardboard and old sacking, lengths of rope, rusty nails and

bed springs, broken crockery and endless bits and pieces picked up on his

walks. Often these objects were the inspiration he needed to spark a

composition, supplying 'the shock which suggests the form just as cracks in a

wall suggested shapes to Leonardo'. Sometimes, just a splotch of colour on a

canvas, a dribble of turpentine or an escaping thread would do the same.

LASTING INFLUENCE

Miro's

influence on 20th-century artists has been enormous. His fascination with

textures and his free, spontaneous creations inspired the tachiste painters and

'action' painters like Jackson Pollock, while his strange, naive characters

were taken up by the Art Brut painters after the Second World War. His

enormously varied output, covering painting, sculpture, ceramics, collages,

etchings, engravings and lithographs, remains a continuing source of

inspiration.

Dutch Interior I

In

1928, Miro paid a brief visit to Holland, where he was intrigued by the

detailed realism of Dutch 17th-century genre paintings in Amsterdam's

Rijksmuseum. He returned to Paris with a few postcard reproductions of the

pictures he had seen, from which he painted his own series of 'Dutch

Interiors'. Dutch Interior I was based on Hendrick Sorgh's Lutanist of 1661.

Miro, however, transformed the original with the medieval logic of the

Romanesque Catalan artists, painting important things large and unimportant

things small - and sometimes removing them altogether. Instead of the lyricism

of Sorgh's picture, Miro's 'Dutch Interior' has a frenzied, dancing rhythm.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Roguish Humour

Roguish Humour  In

Paris, Miro was encouraged to develop his imaginative faculties by the

Surrealist poets and artists that he met. Fascinated by their experiments with

summoning up the unconscious through states of hallucination, he would sit for

hours in his studio capturing the strange sensations and forms he experienced

when hallucinating himself through extreme hunger. The artistic freedom of this

method was vital to his creative development: from the early 1920s onwards,

Miro no longer used space and colour in a realistic way to depict everyday

objects, and the forms that appeared in his paintings became a personal

language of signs and symbols.

In

Paris, Miro was encouraged to develop his imaginative faculties by the

Surrealist poets and artists that he met. Fascinated by their experiments with

summoning up the unconscious through states of hallucination, he would sit for

hours in his studio capturing the strange sensations and forms he experienced

when hallucinating himself through extreme hunger. The artistic freedom of this

method was vital to his creative development: from the early 1920s onwards,

Miro no longer used space and colour in a realistic way to depict everyday

objects, and the forms that appeared in his paintings became a personal

language of signs and symbols. Miro's

Catalan peasants became stick-like figures, for example, recognizable by their

attributes: Phrygian cap and a pipe perhaps or a wedge-shaped hunter's knife

and gun. Many of Miro's humorous figures look naive and unsophisticated, like

children's doodles, and he was deliberately trying to evolve an art that would

stimulate basic sensations of humour, fear, excitement and passion in the

spectator; to 'rediscover the religious and magic sense of things, which is

that of primitive peoples'. He developed his new figures by a process of

simplification, a stripping away of unnecessary details. 'Showing all the

details', he said, 'would deprive them of that imaginary life that enlarges everything.'

Miro's

Catalan peasants became stick-like figures, for example, recognizable by their

attributes: Phrygian cap and a pipe perhaps or a wedge-shaped hunter's knife

and gun. Many of Miro's humorous figures look naive and unsophisticated, like

children's doodles, and he was deliberately trying to evolve an art that would

stimulate basic sensations of humour, fear, excitement and passion in the

spectator; to 'rediscover the religious and magic sense of things, which is

that of primitive peoples'. He developed his new figures by a process of

simplification, a stripping away of unnecessary details. 'Showing all the

details', he said, 'would deprive them of that imaginary life that enlarges everything.'

Miro

felt free to distort and rearrange as his imagination dictated, and to place

anatomical forms arms, heads, breasts, hands and feet and other signs in

comical juxtapositions. Some of his paintings, like Harlequin's Carnival, are

very light-hearted and humorous, as if Miro took a childish delight in

arranging his toys, but his forms have also been described as 'torture

instruments'.

Miro

felt free to distort and rearrange as his imagination dictated, and to place

anatomical forms arms, heads, breasts, hands and feet and other signs in

comical juxtapositions. Some of his paintings, like Harlequin's Carnival, are

very light-hearted and humorous, as if Miro took a childish delight in

arranging his toys, but his forms have also been described as 'torture

instruments'.

0 Response to "Spainish Great Artist Joan Miro - Roguish Humour"

Post a Comment