Great

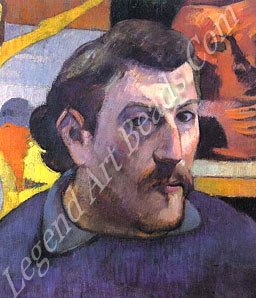

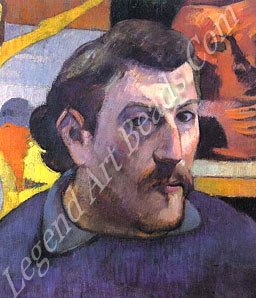

Artist Paul Gauguin Life

Great

Artist Paul Gauguin Life

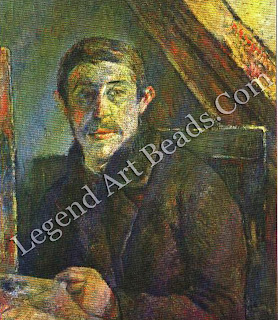

Paul Gauguin was one of the

most revolutionary painters of the 19th century, as unconventional in his art

as he was in his lifestyle. At the age of 35 he abandoned a respectable

business career to devote himself to painting, and his desire for personal and

artistic freedom eventually made him an outcast from society. His final years

were spent in the South Seas: poor, ill and often without proper materials for

painting.

Gauguin soon reacted against

the light-hearted style in which he began his career and turned to weightier

subjects. His bold colours and shapes expressed his own inner vision rather

than external reality. When he died, Gauguin was virtually forgotten, but an

exhibition of his work in Paris three years later revealed his genius, and

since then he has been one of the greatest influences on 20th-century art.

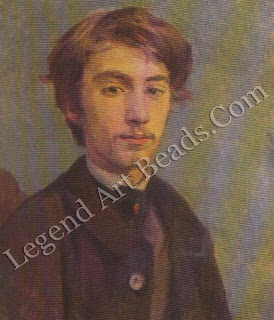

Stockbroker

in the South Seas

When he became a stockbroker at

the age of 23, Gauguin seemed to have settled for a conventional middle-class

life. But adventure was in his blood, and 12 years later he risked everything

for art.

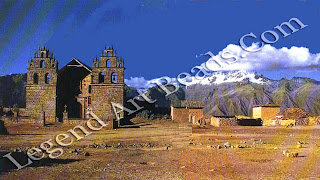

Paul Gauguin was born in Paris

on 7 June 1848. His father Clovis was a radical journalist, and there was

radical blood on his mother's side, tooAline was the daughter of the

Peruvian-born feminist and socialist Flora Tristan. But the year of Paul's

birth was a bad time for radicals. By November 1848, Louis Napoleon had seized

power in France, and his political opponents had a tendency to disappear.

Clovis decided to visit his wife's relatives, and the family sailed to Peru in

1849.

Clovis died of a heart attack

on the journey from France, but Aline, with Paul and his sister Marie, spent

the next six years in Lima under the protection of her great-uncle. Then Paul's

grandfather died in France, and the family returned to take up their

inheritance in the old man's home town of Orleans.

Dull, provincial and thoroughly

bourgeois, Orleans was a depressing contrast to colourful, subtropical Peru,

and Paul hated it. When he was 17, he did what thousands of restless, adventurous

young men had done before him: he went to sea. He worked for three years on a

merchant vessel, and when he became due for military service in 1868, he chose

to serve his stint in the navy.

Paul was released from the

service in 1871, and it seemed he had got the taste for adventure out of his

system. He was 23, and it was time for him, as a young man of respectable

family, to settle down. His mother had died while he was still at sea, but had

previously arranged for the wealthy banker Gustave Arosa to be Paul's guardian.

Arosa was happy to use his contacts to find him a post with a leading Paris

stockbroker.

A

BUSINESS CAREER

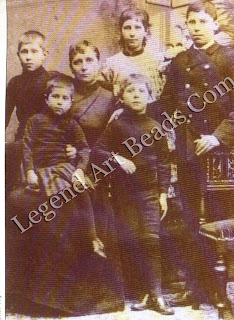

Gauguin's clerkship was a

comfortable, well-paid job, and it gave him plenty of opportunity for lucrative

speculation on the stock exchange. An affluent middle-class future seemed

assured. In 1873 he married a Danish girl, Mette Sophie Gad, and they

progressed from a fine apartment in town to an even finer suburban house, as

Mette regularly produced the next generation of Gauguin’s. By 1883, he had

money, a business reputation, a good home and five children.

But Gauguin had developed a

hobby he liked to paint. His interest in art was encouraged by his guardian,

who had a fine collection of paintings and in whose house most of the

best-known painters of the day appeared from time to time. Gauguin was

encouraged also by Arosa's daughter, an amateur painter, and in 1874 he had

some lessons with the Impressionist Camille Pissarro. But essentially he was

self-taught.

At Arosa's house and elsewhere,

Gauguin had met the leading Impressionist painters and even started to buy

their work. He began to align himself with them, exhibiting in their group

shows from 1879 onward. His paintings came in for a fair amount of praise, and

they sold quite well. Gauguin must have toyed for some time with the idea of

turning professional, but in 1882 his mind was made up for him by a

stock-market crash. Gauguin's 'secure' job suddenly looked anything but secure.

In 1883, confident of his ability to keep his family by painting, he resigned.

Unfortunately, the general

climate of bankruptcy and despondency had much the same effect on the art

market as on the stock market. By 1884, Gauguin's savings had run out, he had

sold scarcely a painting and although a move from Paris to Rouen in Normandy

had reduced his household expenses, his family was fast approaching

destitution. Mette now took a hand. Her husband had had a year as a painter and

failed; now she insisted the family move to her native Denmark.

DESERTING

THE FAMILY

But their move was not a

success. Although Gauguin found a job as a sales representative for a

manufacturer of tarpaulins, he sold no more of his company's goods than he had

of his paintings. Besides, his commitment to his art was now becoming total.

Gauguin returned to painting and in 1885 left once more for Paris, leaving

Mette with four children in Copenhagen. He took six-year-old Clovis with him.

The following year was perhaps

the worst in Gauguin's life. By the winter of 1885-6, he was penniless, and he

and his son were reduced to living in one miserable room. Cold and

undernourished, the boy contracted smallpox; to feed him, Gauguin managed to

find work as a bill-poster for a railway company. Remarkably, Clovis recovered,

but it was the last time Gauguin did anything for his family. From now on,

their fate was in Mette's hands.

In June, Gauguin moved once

more, to Pont-Aven in Brittany, where he found not only cheap lodging but the

company of appreciative fellow-artists. But there was no financial success to

match his growing confidence. Returning to Paris at the end of 1886, he almost

starved during the winter. The following year, he decided to make a complete

break. 'Paris,' he wrote, 'is a desert for a poor man. I must get my energy

back, and I'm going to Panama to live like a native.'

Somehow he scraped together the

fare, but 'living like a native' in Panama turned out to mean labouring with

pick and shovel in the abortive canal project then under way. After a few

weeks, sick with fever, he gave up on Panama and ventured to Martinique in the

French West Indies. Four months later, ill-health and poverty forced him back

to France, and he returned to Brittany.

Somehow he scraped together the

fare, but 'living like a native' in Panama turned out to mean labouring with

pick and shovel in the abortive canal project then under way. After a few

weeks, sick with fever, he gave up on Panama and ventured to Martinique in the

French West Indies. Four months later, ill-health and poverty forced him back

to France, and he returned to Brittany.

A

VISIT TO VAN GOGH

Creatively, this was a vital

period. At the age of 40, he was finding himself at last as a great and

original painter. But the Brittany winters de-pressed him. In October 1888, he

accepted an invitation from Vincent van Gogh, whom he had met two years earlier

in Paris, to pass the winter with him at Arles, in the South of France. But

Gauguin had been there only two months when Van Gogh went famously insane, and

threatened him with a razor. There was nothing for it but to return to Paris.

Over the next few years,

Gauguin alternated between Paris and Brittany, producing some of his best work.

His reputation among his contemporaries had never been higher, but he was still

desperately short of money, and he had never lost his yearning to return to the

tropics. Finally he settled on another French colony Tahiti and on 1 April 1891,

he sailed from Marseilles.

At first, Tahiti was not what he had hoped

for. He got a friendly reception from the Governor, and an audience was

arranged for him with the last native king, Pomare V, who Gauguin hoped would

prove a source of commissions. But Pomare died suddenly of drink a few hours

before the audience. Soon Gauguin was disgusted with the capital of Papeete.

'It was Europe all over again,' he wrote, 'just what I thought I had broken

away from made still worse by colonial snobbery.'

In the country district of

Mataiea, however, Gauguin found the peace he wanted and a young Tahitian girl

to share his hut. Even in paradise, though, the need for money reared its ugly

head. Despite his dreams, Gauguin could not live for free. He lacked the skills

to fish or to farm, and in a community of self-sufficient families there was no

real possibility of buying food. He had to rely on expensive and incongruous

European canned and dried produce, bought in Papeete. A spell of ill-health

made further inroads into his savings, and in 1893 he had to apply to the

Governor to have him-self repatriated to France.

RETURN

TO TAHITI

It was a humiliating return,

but the canvases that Gauguin brought back with him persuaded a leading Paris

gallery-owner to give him an exhibition. Though sales were poor, Gauguin found

himself the centre of the art world's interest. And he had a financial

windfall: an uncle back in Orleans died and left him enough money to set up his

own studio in Montparnasse. But he was determined to return to Tahiti, and left

France for the last time in July 1895.

The eight years that remained

to him were great ones for his art, but Gauguin's life was often miserable.

Most of the times he was desperately short of money and could rarely afford the

stays in hospital that his worsening health due to syphilis demanded. In 1897,

he even attempted suicide. The following year, he contemplated abandoning

painting, and had to take a miserable job as a draughtsman to pay off at least

some of his debts.

Disgusted by colonial society

and its effects on the Tahitians, Gauguin took to writing vitriolic articles

for a local newspaper. In 1901, he abandoned the island altogether and made the

800-mile journey to the Marquesas Islands, where he settled in the village of

Atuona. There, he built his last dwelling, 'The House of Pleasure', as he

called it. Money at last was coming from Paris, and Gauguin was working happily

as well as hard. But he was still making enemies. His attacks on the colonial

administration continued and he waged a continuous war with the Catholic

Church.

In 1903, the authorities took

their revenge. Gauguin was sentenced to three months' imprisonment for

'defamation'. He never served the sentence. On 8 May 1903, aged 54, he died

while awaiting the result of an appeal. The local bishop wrote an uncharitable

epitaph. 'The only noteworthy event here has been the sudden death of a

contemptible individual named Gauguin, a 3: reputed artist, but an enemy of

God.' Posterity had a different verdict.

Writer – Marshall Cavendish

Somehow he scraped together the

fare, but 'living like a native' in Panama turned out to mean labouring with

pick and shovel in the abortive canal project then under way. After a few

weeks, sick with fever, he gave up on Panama and ventured to Martinique in the

French West Indies. Four months later, ill-health and poverty forced him back

to France, and he returned to Brittany.

Somehow he scraped together the

fare, but 'living like a native' in Panama turned out to mean labouring with

pick and shovel in the abortive canal project then under way. After a few

weeks, sick with fever, he gave up on Panama and ventured to Martinique in the

French West Indies. Four months later, ill-health and poverty forced him back

to France, and he returned to Brittany.

0 Response to "Great French Artist - Paul Gauguin's Life"

Post a Comment