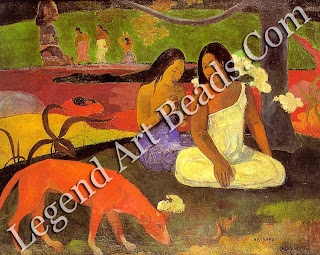

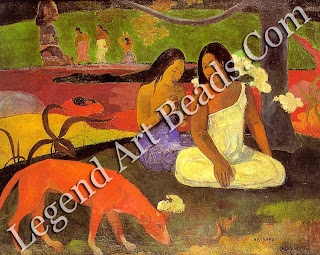

The exotic culture of the South

Sea Islands held a powerful fascinatio for Gauguin, who

chose strange, vivid colours to express the beauty and the

mystery he experienced there.

Paul Gauguin was in his early

twenties when he took up painting. At first art was no more than a hobby, but

he admired and bought the work of the early Impressionists, and based his own

style on theirs. As his dedication grew, however, Gauguin soon realized that

although these artists, with their bright colours and bold technique, had freed

painting from traditional bonds, Impressionism too was limited in scope.

Gradually he moved forward to develop the ideas that made him with Van Gogh and

Cezanne one of the greatest of the Post-Impressionist artists.

The Impressionists had painted

the natural world with vividness and directness. But Gauguin was fascinated by

ideas more than appearance and wanted his art to express strong emotions:

'Where does the execution of a picture start, where does it end? At the moment

when intense feelings are found in the depth of one's being, when they erupt,

and thought flows forth like lava from a volcano. Cold and rational calculation

have nothing to do with this eruption, for who knows when, in the depths of his

being, the work was begun, perhaps unconsciously?' To express such intensity of

feeling, Gauguin had to develop a radically new style of painting.

He rejected the idea that a

painting had to represent something we can see in the real world, and drew

fresh inspiration from non-European art Gauguin was one of the first artists to

take a serious interest in 'primitive' cultures. He spoke of his own 'savage

blood', and, perhaps recalling his childhood in Peru, he felt a strong affinity

for the vigour of prehistoric Central and South American art. He saw numerous

examples of this type of work at the Paris World's Fair of 1889.

He rejected the idea that a

painting had to represent something we can see in the real world, and drew

fresh inspiration from non-European art Gauguin was one of the first artists to

take a serious interest in 'primitive' cultures. He spoke of his own 'savage

blood', and, perhaps recalling his childhood in Peru, he felt a strong affinity

for the vigour of prehistoric Central and South American art. He saw numerous

examples of this type of work at the Paris World's Fair of 1889.

REVOLUTIONARY

COLOUR

Gauguin also looked for

inspiration to Egyptian and Cambodian sculpture, to medieval art and to

Japanese prints. He collected postcards of painting and sculpture in a way that

is now commonplace among artists and students, but which at the time was novel.

In the expressive power of his colour, however, Gauguin went beyond any of his

sources. The Vision after the Sermon, one of his most revolutionary

paintings, used bright red completely unnaturalistically to set the emotional

tone of the painting one of visionary intensity.

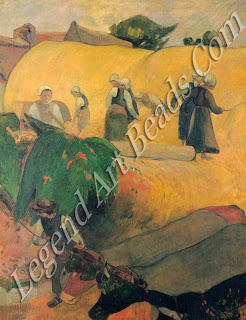

The Vision after the Sermon was

painted at Pont-Aven, where Gauguin briefly inspired a group of like-minded

artists. But his personal style reached its fullest flowering in Tahiti.

Gauguin's taste for religious and symbolic themes was richly sustained by the

native traditions; the bright light produced the strong colours he loved; and

the exotic beauty of the islanders made an over-whelming impact on him. He

thought that his native models 'possessed something mysterious and penetrating,

not beauty in the strict sense of the word. They move with all the suppleness

and grace of a sleek animal, giving off that smell which is a mixture of animal

odour and the scents of sandalwood and gardenia.'

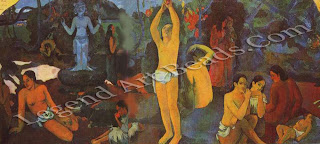

One of the most characteristic

features of Gauguin's work in Tahiti is his use of flat, frieze-like

compositions, in which he was perhaps influenced by Egyptian art. This kind of

corn-position, in which Gauguin's imposing figures 'indescribably august and

religious in the rhythm of their gestures' are arranged across the foreground,

with little sense of depth, creates a mood of solemn majesty.

Gauguin's technique in the

Tahiti paintings was no less distinctive than his composition. Materials were

not easily available, so he often had to use coarse sacking rather than proper

canvas, spreading his paint thinly to make it go further. From adversity he

extracted inspiration, for the limitations of his materials forced him to paint

with a rough vigour appropriate to his bold vision.

When Gauguin died in 1903, very

few people would have agreed with his words in a letter to his wife: `I am a

great artist and I know it. It is because I am, that I have endured such

suffering.' Three years after his death, however, 227 of his works were shown

in a major exhibition in Paris; this firmly established his reputation among

more progressive artists and his subsequent influence on 20th-century art has

been immense. The emotional impact of his work and his complete dedication to

art whatever the cost in personal suffering have made him, like his friend Van

Gogh, one of the cult heroes of modern times.

When Gauguin died in 1903, very

few people would have agreed with his words in a letter to his wife: `I am a

great artist and I know it. It is because I am, that I have endured such

suffering.' Three years after his death, however, 227 of his works were shown

in a major exhibition in Paris; this firmly established his reputation among

more progressive artists and his subsequent influence on 20th-century art has

been immense. The emotional impact of his work and his complete dedication to

art whatever the cost in personal suffering have made him, like his friend Van

Gogh, one of the cult heroes of modern times.

Writer – Marshall Cavendish

He rejected the idea that a

painting had to represent something we can see in the real world, and drew

fresh inspiration from non-European art Gauguin was one of the first artists to

take a serious interest in 'primitive' cultures. He spoke of his own 'savage

blood', and, perhaps recalling his childhood in Peru, he felt a strong affinity

for the vigour of prehistoric Central and South American art. He saw numerous

examples of this type of work at the Paris World's Fair of 1889.

He rejected the idea that a

painting had to represent something we can see in the real world, and drew

fresh inspiration from non-European art Gauguin was one of the first artists to

take a serious interest in 'primitive' cultures. He spoke of his own 'savage

blood', and, perhaps recalling his childhood in Peru, he felt a strong affinity

for the vigour of prehistoric Central and South American art. He saw numerous

examples of this type of work at the Paris World's Fair of 1889.  When Gauguin died in 1903, very

few people would have agreed with his words in a letter to his wife: `I am a

great artist and I know it. It is because I am, that I have endured such

suffering.' Three years after his death, however, 227 of his works were shown

in a major exhibition in Paris; this firmly established his reputation among

more progressive artists and his subsequent influence on 20th-century art has

been immense. The emotional impact of his work and his complete dedication to

art whatever the cost in personal suffering have made him, like his friend Van

Gogh, one of the cult heroes of modern times.

When Gauguin died in 1903, very

few people would have agreed with his words in a letter to his wife: `I am a

great artist and I know it. It is because I am, that I have endured such

suffering.' Three years after his death, however, 227 of his works were shown

in a major exhibition in Paris; this firmly established his reputation among

more progressive artists and his subsequent influence on 20th-century art has

been immense. The emotional impact of his work and his complete dedication to

art whatever the cost in personal suffering have made him, like his friend Van

Gogh, one of the cult heroes of modern times.

0 Response to "Paul Gauguinsteries of Paradise"

Post a Comment