I shall keep cautioning readers about the use of 'philosophy' and

'philosophical' in our context. Historians of western philosophy beginning with

Erdmann and uberweg in the last century, and continuing with virtually all academically

philosophers of the western world up to date have denied Indian thought the

title 'philosophy'. Enologists and oriental scholars, however, have been using

the term for Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain thought quite indiscriminately and this

did not matter too much because there was and there is the assumption that the

twain, professional orient lists and professional philosophers do not meet. I

think this is wrong. It is extremely difficult to make them meet, because a lot

of cross disciplinary studies are needed for both the philosophers will have to

read some original tracts of Indian thought and its paraphrase in other Asian

languages; and the orient lists will have to acquire sonic knowledge of

contemporary philosophy, especially on the terminological side. This has not

been done: scholars who wrote and write on Indian ' philosophers ' Stcherbatsky

, Raju, Glasenapp, Edgerton, Radhakrishnan, to mention but a few did not

seriously attempt to read modern philosophy and use its accurate terminology.

All of them somehow assume that western philosophy had reached its climax with

Kant, Hegel, or Bradley, and hence they do not feel the need to improve on

their archaic terminology. I Think

they are mistaken. Terminologies previous to that of the analytical schools of

twentieth century philosophy are deficient.' It could be objected that

contemporary occidental philosophy may be unequal to the task of providing

adequate terminology for Indian thought patterns; this may be so, but pre twentieth

century occidental philosophy is even less adequate; modern philosophy uses all

the tools of the classical philosophical tradition, plus the considerably

sharper and more sophisticated tools of multi value logic, logical empiricism,

and linguistic analysis.

I shall keep cautioning readers about the use of 'philosophy' and

'philosophical' in our context. Historians of western philosophy beginning with

Erdmann and uberweg in the last century, and continuing with virtually all academically

philosophers of the western world up to date have denied Indian thought the

title 'philosophy'. Enologists and oriental scholars, however, have been using

the term for Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain thought quite indiscriminately and this

did not matter too much because there was and there is the assumption that the

twain, professional orient lists and professional philosophers do not meet. I

think this is wrong. It is extremely difficult to make them meet, because a lot

of cross disciplinary studies are needed for both the philosophers will have to

read some original tracts of Indian thought and its paraphrase in other Asian

languages; and the orient lists will have to acquire sonic knowledge of

contemporary philosophy, especially on the terminological side. This has not

been done: scholars who wrote and write on Indian ' philosophers ' Stcherbatsky

, Raju, Glasenapp, Edgerton, Radhakrishnan, to mention but a few did not

seriously attempt to read modern philosophy and use its accurate terminology.

All of them somehow assume that western philosophy had reached its climax with

Kant, Hegel, or Bradley, and hence they do not feel the need to improve on

their archaic terminology. I Think

they are mistaken. Terminologies previous to that of the analytical schools of

twentieth century philosophy are deficient.' It could be objected that

contemporary occidental philosophy may be unequal to the task of providing

adequate terminology for Indian thought patterns; this may be so, but pre twentieth

century occidental philosophy is even less adequate; modern philosophy uses all

the tools of the classical philosophical tradition, plus the considerably

sharper and more sophisticated tools of multi value logic, logical empiricism,

and linguistic analysis.

However,

with some very few exceptions, authors on Indian thought, both western and

Indian, have not tried to acquire and use these better tools they have so far

been satisfied to carry on with the philosophically outdated tools of the

European traditions of the last two centuries, especially of the Fichte Kant Hegel

tradition, widened in size, but not in quality, by additions of such British

philosophers as Bradley and Bosanquet. Exceptions so far have been few:

Professor Ingalls at Harvard, and his student Professor K. Potter, are known to

this author to avail themselves of contemporary philosophical terminology when

dealing with Indian material; and Professor H. V. Guenther, formerly at

Banaras, who consciously and determinedly capitalizes on the work of such

thinkers as C. D. Broad, Ayer, Russell, Wisdom, Veatch, Straw son, Ullmann, and

a large number of less known British and American teachers of philosophy.

If I

may venture a guess as to why writers on Indian philosophy refused to acquire

and use more up to date tools, I believe the main reason is not so much inertia

but the idea that Kant, Hegel, and Bradley, etc., were spirits more kindred to

the Indians; that their idealistic or at least metaphysical predilections

qualified them better for the providing of interpretative concepts than the

twentieth century anti metaphysical, anti systematic, anti 'idealistic'

philosophers (idealistic' in the popular, non philosophical sense, and emotive

equivalent of 'truth seeking' as opposed to Tact seeking'). Here again they

err; in the first place, the great philosophers of the European eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries were no more favorably inclined towards Indian philosophy.

Than

are modern analytical thinkers; but more importantly, the fact of a system of

thought being closer in emotive tone to another system of thought does not guarantee

that the former is a competent arbiter of the latter. This wrong assumption

goes back to an even older historical phenomenon the great attraction, largely

sentimental, which nineteenth century German classical scholars and poets felt

for things Indian in the belief of a 'kindred sour; this is being echoed in

India by the majority of pandits and holy men: it is very hard to convince

pandits and monks in India that Sanskrit is not taught and spoken in high

schools in Germany, and that Germans are not the only Sanskrit scholars outside

India.

Than

are modern analytical thinkers; but more importantly, the fact of a system of

thought being closer in emotive tone to another system of thought does not guarantee

that the former is a competent arbiter of the latter. This wrong assumption

goes back to an even older historical phenomenon the great attraction, largely

sentimental, which nineteenth century German classical scholars and poets felt

for things Indian in the belief of a 'kindred sour; this is being echoed in

India by the majority of pandits and holy men: it is very hard to convince

pandits and monks in India that Sanskrit is not taught and spoken in high

schools in Germany, and that Germans are not the only Sanskrit scholars outside

India.

I

therefore submit that students of Indian philosophy should learn to use the

more precise terminology of contemporary western philosophy when they attempt

to translate and define Indian philosophical texts. From this standpoint it

might have been wise to substitute 'philosophy by some such word as 'ideology'

or 'speculative patterns' fur the bulk of Indian (and hence Tibetan) scholastic

lore; in fact, short of logic (nyaya, tarka), Indian philosophy has been

ideology. Yielding to the majority, however, we shall continue to refer to

these patterns including tantric patterns

as 'philosophy', bearing the said strictures in mind. Indian thought

does not contain much of what modern philosophers would call 'philosophy' but they would not object to tantric thought

being added as a new branch of investigation: as 'psycho experimental speculation.

I recommend this lengthy phrase, because it summarizes tantric 'philosophy';

but I shall not use it unless it proves acceptable to scholars at some later

date; I shall use 'philosophy' in this book, but whenever I speak about tantric

'philosophy' it is to be understood as shorthand for 'psycho experimental speculation'.

If the

old philosophical terminology is used the contents of most Indian systems can

indeed be told in very few words, but I am convinced that this succinctness is

as deceptive and vague as the terminology of classical philosophy. It is this

deceptiveness to which an Indian scholar like S. B. Dasgupta succumbed when he

wrote about tantric literature, that it was:

An

independent religious literature, which utilized relevant philosophical

doctrines, but whose origin may not be traced to any system or systems of

philosophy; it consists essentially of religious methods and practices which

have been current in India from a very old time. The subject matter of the

tantras may include esoteric yoga, hymns, rites, rituals, doctrines and even

law, medicine, magic and so forth

The

same scholar quotes a Buddhist tantric definition of tantrism, 'tanyate vistriyate

panamanerta its tantrain'. Now the ideologist who uses classical occidental

terminology would render this' that by which knowledge (or wisdom, intuition,

etc.) is extended or elaborated, is tantras. The vagueness of this

translation unnoticed by ideologists

because they are so used to it rests on an inadequate rendition of ‘pawl’;

without going into an elaborate analysis of 'pond , let me say that `wisdom' or

'intuitive wisdom' arc too vague, and for Buddhist tantras incorrect. Professor

Guenther translates judna 'analytical appreciative understanding', and this is

borne out by the Sanskrit definition; for if jiidna were the immutable wisdom,

say, of the Vedantic variety, it could neither be extended nor elaborated. The

Brahmanical or at least the Vedanta monist's jficita is a state of being, not

one of knowing; the rootpa, in its Vedantic sense, does not connote cognition,

but the irrefutable intuition of a single, all including entity, other than

which nothing persists; vet, even the term 'intuition' is not really adequate

here, because it still implies an intuiting subject and an intuited object,

whereas the Vedantic jiicina does not tolerate any such dichotomy.

We must

now show what philosophy is common to all Indian schools of religious thought;

and then, what philosophy is common between Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism of

the tantric variety; we can omit Theravada Buddhism and Jainism from the

survey, because their axiomatic differences are too great on all levels from

the subject matter of this study. It is not advisable to try to list here the

differences between tantric and non tantric forms of Hinduism and Buddhism,

simply because they are not of a philosophical order. In other words, there is

nothing in Buddhist and Hindu tantric philosophy which is not wholly contained

in some non tantric school of either.

Or to

put it differently, tantrism has not added any philosophical novelty to

Hinduism and Buddhism; I do not even think that it emphasizes certain aspects

of Mahayana or Hindu philosophy more than do the respective non tantric

doctrines preceding it. To give an illustration: The Madhyamikas teach and

emphasize the complete identity of nirvana and samsara, i.e. of the absolute

and the phenomenal modes of existence; the Vajrayana Buddhists take this notion

for granted it is on the ritualistic or contemplatively methodical side that

differences arise, and these are indeed fund a mental. In a similar fashion the

non tantric monists or Sivites (Samkaracarya and his school, or the Southern

Siva Agama teachers), pronounce and emphasize the oneness of Siva and Sakti,

and so do the Hindu tantric of the Sakta schools they do not add any

philosophical or speculative innovation to their non tantric antecedents but

they do different things and practice different sadhana (contemplative

exercises). There is thus no difference between tantric and non tantric

philosophy, as speculative eclecticism is pervasive; there is all the

difference in the practical, the sad hand part of tantrism.

There

are perhaps just two elements common to all Indian philosophy: first, the axiom

of inevitable metempsychosis (this is shared with all religious systems

indigenous in India) and the notion of possible emancipation connected with the

former as the apodosis of a single proposition, the axiom of metempsychosis

being its protasis.

The

second common clement is the notion of some absolute which underlies the

phenomenal universe. Indian scholars and other votaries of the oneness of all

religions have postulated that the Vedantic Brahman and the Mahayanist s'anya

are the same concept, the difference being merely terminological. I shall with hold

my judgment on this point at present. If sunya and the brahtnan are concepts

which lean on the same proclivity to absolutize the permanent as experienced or

inferred. Beneath or alongside with the ephemeral, this would not suffice to

establish the identity of sunyata and the Brahman. The Mahayana Buddhist Would

certainly reject this identification, and the possible re joinder that he does

so because he has to insist on being fund a mentally different from the Brahmin

tradition is not justified until there is a precise analytical formulation of Brahman

and sunyata juxtaposed. No such formulation has come forth so far.

The

element common to Hindu and Mahayana philosophy is what Indian scholastic

methodology calls samanvaya, i.e. The institutionalized attitude of reconciling

discursively contrary notions by raising them to a level of discourse where

these contra dictions are thought to have no validity. It is due to samanvaya

that the gap between the phenomenal (samvrti, vyavahara) and the absolute

(paramartha) truths spares the Hindu or Mahayana thinker the philosophical

embarrassment the outsider feels when he views paramartha and vyavahara

philosophy side by side, in Indian religious literature.

What

distinguishes tantric from other Hindu and Buddhist teaching is its systematic

emphasis on the identity of the absolute (paramartha) and the phenomenal

(vyavahara) world when filtered through the experience of sadhanc. Tantric

literature is not of the philosophical genre; the stress is on sadhana. But it

seems to me that one philosophical doctrine inherent in esoteric Hinduism and

Mahayana Buddhism especially of the Madhyamikas

school the identity of the phenomenal

and the absolute world was singled out

by all tantric teachers as the nucleus around which all their speculation was

to revolve; I also believe that the dictionary discrepancies between the

various schools of speculative thought are really resolved in tantric sadhana:

all scholastic teachers in India declare that there is samanvaya, but the

tantric actually experiences it; I have tried to elaborate a model of this

phenomenon, which had been suggested to me by my own preceptor, the late

Visvananda Bharati.

The

other philosophical doctrine common to Hindu and Buddhist tantra is probably

due to some sort of dictionary diffusion. It is of the type of a universe model:

reality is one, but it is to be grasped through a process of conceptual and

intuitive polarization. The poles are activity and passivity, and the universe

'Work' through

their interaction. The universe ceases to 'work' i.e.

its state of absolute oneness and quiescence is realized when these two poles

merge. They are merged doctrinarily by the repeated declaration of their

fundamental oneness, and are experienced by the tantric reliving of this merger

through his integrating scidhanci or spiritual disciplines.

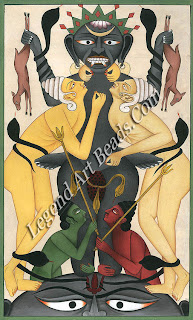

Only

this much is really common between Hindu and Buddhist tantric doctrines, for

their respective ascriptions to the two poles are obverse to each other. The

Hindu assigned the male symbol apparatus to the passive, the female to the active

pole; the Buddhist did the opposite; the Hindu assigned the knowledge principle

to the passive male pole, and the dynamic principle to the active female pole;

the Vajrayana Buddhist did it the other way round.

All

tantric philosophy sets forth the power of a conceptual decision, notwithstanding

the fact that the execution of ritualistic contemplation is carried out in

minute detail. It appears that conceptual decision leading to permanent

enstasis (piano, bodhi) has higher prestige than other procedures. Thus we find

this statement in the account of a Tibetan teacher:

By a

doctrine which is similar to the application of fat to a wound when an arrow

piece remains inside, nothing can be reached; by a doctrine which is similar to

tracing the footsteps of a thief to a monastery when he had escaped to the

forest and mountain, nothing can be gained, so also having declared one's own

mind to be non substantial (by its nature), the fetters of the outside world

will fall off by themselves, because all is sunyata.

I have

no scriptural evidence for this surmise, but I feel that the tendency to

supersede the necessity of minute exertion by a basically intellectual act is a

typical tantric element of speculation. We find an important analogy in

orthodox Brahmanical thought: Samkaracarya declared that the cognitive

understanding of the meaning of the four great Upanisadic dicta, 'this atma is

brahma',`I am Brahma', `thou art that', and `the conscious self is Brahma,

results in immediate liberation. Most of his contemporaries and particularly

his later opponents (especially Ramanuja in the Eleventh century, and his

school) opposed this notion vehemently, insisting on prolonged observance and

discipline. Samkaracarya’s attitude towards tantra is ambivalent, but there is

reason to believe that he was profoundly influenced by tantric notions.

Romanticizing

German ideology was highly enthusiastic about Indian thought, and this is one

of the reasons why Hindu pandits are full of praise for German ideology. Thus,

H. V. Glasenapp wrote the notion that the whole universe with the totality of

its phenomena forms one single whole, in which even the smallest element has an

effect upon the largest, because secret threads connect the smallest item with

the eternal ground of the world, this is the proper foundation of all tantric

philosophy.

There

is decidedly such a thing as a common Hindu and Buddhist tantric ideology, and

I believe that the real difference between tantric and non tantric traditions

is methodological: tantra is the psycho experimental interpretation of non tantric

lore. As such, it is more value free than non tantric traditions; moralizing,

and other be good clichés are set aside to a far greater extent in tantrism

than in other doctrine. By 'psycho-exper- mental' I mean given to experimenting

with one's own mind', not in the manner of the speculative philosopher or the

poet, but rather in the fashion of a would be psychoanalyst who is himself

being analyzed by some senior man in the trade. This, I think, is the most

appropriate analogue in the modern world: the junior psychoanalyst would be the

disciple, the senior one the guru. The tantric adept cares for liberation, like

all other practicing Hindus or Buddhists; but his method is different, because

it is purely experi-mental in other words, it does not confer ontological or

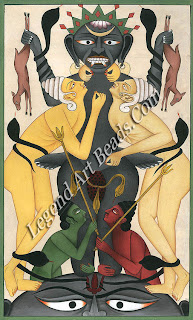

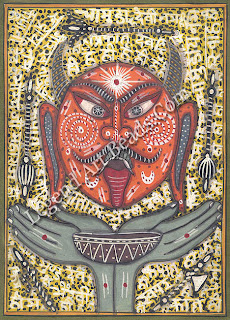

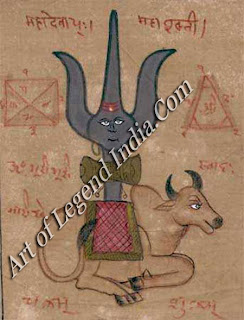

existential status upon the objects of his meditations. This is the reason why tantric

are not in the least perturbed by the proliferation of gods and goddesses,

minor demons and demo nesses, and other creatures of various density and efficacy they do not attempt to reduce their number,

for these are necessary anthropomorphic ways of finding out 'what is inside the

mind'. The tantric entertains one or two axioms, no doubt the absolutistic and

the.

Phenomenal

nominal identity axioms, but they are not really important. Except as

speculative constructs Similarly, the psychologist entertains a few axioms, as

for instance the one identifying sanity with adjustment to the cultural milieu

of his environment which he shares with the anthropologists interested in

`culture and personality', or the axiom that there is such a thing as mental

illness but the practicing analyst is not really interested in these axioms as

he carries on his work in fact, these

axiomatic notions arc quite irrelevant to the execution of his work. They are

'at the back of his mind', but he can leave them there when he works.

To sum

up the rambling question whether or not we should make a distinction between

what is specifically tantric and what is not. On the theological and speculative

level the answer is decidedly yes. All tantric flout traditional, exoteric

orthodoxy, all put experiment above conventional morality denying ultimate

importance to moralistic considerations which is not contradicted by the fact

that most tantric texts pay initial homage to con ventional conceptions of

morality; and all agree that their specific method is dangerous, and radical,

and all claim that it is a shortcut to liberation.

I do

not believe that either the Hindus or the Buddhists were consciously working

out a similar psycho experimental pattern, and I do not think that they were

making a conscious effort to unite Hindus and Buddhists, even though they may

well have been aware of great similarities between their practices. But B.

Bliattacharya's statement the kjilacokra or Circle of Time" as the highest

god was set up by a particular section which wanted that the Hindus should

unite with the Buddhists under the common nonsectarian banner of the Time God Kalacakra

in order to present a united front against the cultural penetration of Semitic

peoples which had already invaded Central Asia and Iran.

Hardly

deserves attention except as a statement a la mode.

Hindu

scholars, with no exception to my knowledge, believe in a virtual dictionary

identity of Advaita monism and Madhya mika absolutism, and this is detrimental

to the study of Indian.

Absolutistic

philosophy, art irrelevant to any tantric study. B.Bhattacharya describes sunya

and the contemplation of it exactly like the Brahman of the Aviate monist; he

refers to the meditative process of the Madhyamikas as 'securing oneness with

the sunya or Infinite Spirit’s I think the similarity of diction and style is a

trap into which Indian scholars readily fall because there is no tradition of

textual criticism in India. Advayavajra, a famous Buddhist tantric teacher,

says: pratibhasa (i.e. apparent reality) is (like) the bridegroom, the beloved

one, conditioned only (i.e. subject to the chain of dependent origination,

pratitya samutpada, Tibetan brel), and sunyata, if She were corpse like, would

not be (likened to) the bride."Now one of India's authorities on Buddhist

tantrism, the late Pandit Haraprasad Sastri, misunderstood this singularly

important passage, when he paraphrased it.

Here.47,

sunyata is the bride and its reflection is the bridegroom. Without the

bridegroom the bride is dead. If the bride is separated, the bride groom is in

bondage.

H. P.

Sastri was probably aware of the fact that the main doctrine of Vajrayaria

theology is essencelessness in the true Buddhist sense. Yet he was misled by

the powerful modern Indian scholastic trend to see Advaita monistic doctrine in

Mahayana Buddhism.18 'Without the bridegroom the bride is dead' this is the exact inverse analogy of the

Hindu tantric dictum `Siva is a corpse without Sakti' (Siivah ,Saktivihinah ,Savah),

which provides an important rule for Hindu tantric iconography." H. P.

Sastri was obviously under the spell of this pervasive tantric proposition,

else it is hard to see why one of the most eminent old time Bengali

Sanskritists should have misinterpreted this important passage.

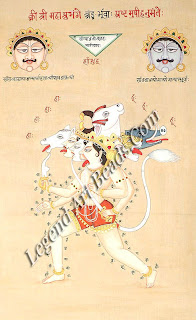

There

is also a subtler reason for the tendency to identify Buddhist and Hindu

tantric doctrine. Buddhist tantrism has borrowed many of its lesser deities

from Hinduism, or at least from the large stock of deities present in areas

which nurtured Hindu, Buddhist, and aboriginal Indian mythology. With the

Indian love for enumeration and classification, mythological groups of 3, 4, 5,

etc., items abound just as they do in doctrinary groups and it is quite irrelevant which came first,

Hindu or Buddhist tantric, in the application of these charismatic group

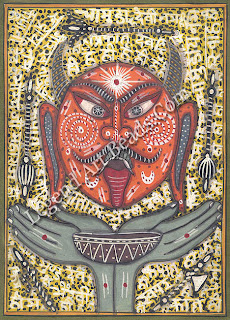

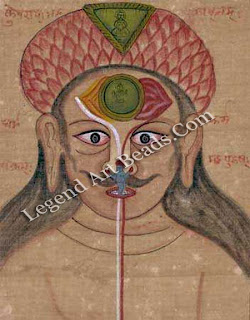

numbers; thus, for example, an old Hindu tantric text2 explains the five faces

of Siva as representing his five aspects as Vamadeva, Tatpurusa, Aghora,

Sadyojata, and Lana, each of which is a frequent epithet of Siva, with slightly

varying modes of meditation prescribed for each of them in Sivites literature.

To these aspects, different colures, different directional controls, etc., are

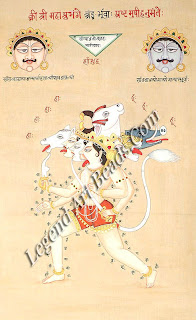

ascribed. The five dhydni Buddha’s also have different colures, directions,

etc., ascribed to them, control over which being the domain of each of the

Buddha’s.

These

arrangements in numeric ally identical groups prompt many scholars to equate

the two mythologies. This is a perfectly permissible procedure if we study

diffusion of concepts as anthropologists; but the moment we extend diffusion

patterns from mythology to philosophy we are tempted to reason fallaciously,

according to the invalid model 'in mythology, Buddhist and Hindu, 3 (4, 5, 7,

etc.) tokens within one theme, therefore in philosophy, Buddhist and Hindu, 3

(4, 5, 7, etc.) tokens within one theme'. We tend to forget that philosophical

concepts, even when they are numbered according to a traditional pattern,

develop and change much more independently than do mythological concepts, for

the simple reason that Indian mythological icons, once created, are hardly ever

modified, because there is no impetus to modbify them on the contrary, the contemplatives feel more

successful if they succeed in visualizing the object in accordance with the

prescribed icon.* There is a lot of impetus, however, to amplify philosophical

doctrines the teaching or the commentary

of a revered preceptor is never as un ambiguous a thing as an icon: in the mind

of the pious scholar, an icon cannot be improved upon, a commentary must be

constantly clarified and amended, due to its inevitable complexity. This

dichotomy in the Hindu and Buddhist scholar's attitude no Modification of

icons, but constant elaboration of philosophical concepts is not shared, say,

by the Roman or Greek Catholic scholar: there are no canons about how Christ's

body or face should be modelled or painted. Hindu and Buddhist iconography

prescribes pictorial icons in exact detail, and there is very little scope for

modification.

The

Hindu scholastic's effort to explain Mahayana doctrine in terms of Vedantic

notions is of course much older than the nineteenth century, but its western

echo or counterpart reinforced the trend. Deussen's generation was not familiar

with medieval Hindu tantric texts which assimilated Vajrayana doctrine into a

Hindu frame. European indology perhaps arrived at this notion independently,

prompted by the inherent romanticism of early indology. In a text which I would

date between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, a Kashmiri scholar discusses

the word makara as a name of the Universal Goddess (Devi); he there describes

her as 'beholding her own body as both sunya and nonsunya which he then glosses

in Vedantic fashion: sunya means of the form of pure mind, but not nonexistent

by nature, and nonsunya means polluted by Maya.

It is

quite possible that Makara was a Hindu tantric goddess, if the name is really a

personification of the `5 m s' pancamakara as it does seem to be. She is not

listed in Bhattacharya's Buddhist Iconography, nor in the fairly exhaustive

Sadhanamala. However, it is impossible to say which deity was Hindu and which

Buddhist in medieval tantric Kashmir. By that time, Hindu scholars had come to

avoid terms like sunya together with other terms of a specifically Buddhist flavor,

and Sitikantha's apology for its use in the prescribed meditation on that

goddess would indicate that her dhycina was originally Buddhist.

Modern

Brahmin scholars, who remain unfamiliar and hence unaffected by occidental

literature on Indian thought, continue to antagonize the Buddhist doctrines

about as vehemently as their classical forbears. Thus, Pdt. Laksminatha Jha,

former Head of the Department of Indian Philosophy at the Sanskrit

Mahavidyalaya, Banaras, says: 'If the root of phenomenal existence be manifest

to Intuition, then what is the foundation of phenomenal existence whereof it is

a manifestation, since everything (according to Madhyamikas) is sunya? Hence, the

doctrine that everything is sunya conflicts with everything, and because it

denies a foundation for anything, it has to be rejected.

It is

as yet impossible for a Hindu or a Buddhist unfamiliar with occidental methods

of philosophical analysis to state the basic difference of Hindu and Buddhist

tantric philosophy without a slant and with objectively valid precision. There

is a lot of precise terminology within the scholastic traditions of India, and

a fortiori of Tibet, but neither the Hindu nor the Buddhist has developed a

terminology sufficient to step out from the atma and no Alma complex. This we

can do at present perhaps only by aid of non Sanskritists analytical language.

This is the situation: the Hindu insists on the notion of a Self, or a

transcendent immanent personality principle, or an atman or Brahman. The

Buddhist, in theory at least, denies any self or any super self. However, in

practice the Vajrayana and to a certain extent all Mahayana Buddhist doctrines

have a sort of Ersatz self or super self, something which defies any treatment

in terms of the Hindu 'entity postulating' languages, yet it has some sort of

subsistence.

Now I

believe that the crux of the matter lies in the fact, not hitherto mentioned by

any scholar known to me, that the principle, or quasi entity which Mahayana and

Vajrayana accepts (Sunyata, Buddhahood, and all the complexes which tantric Buddhism

personifies in its deities, populating the universe with psycho experimentally

necessary and highly ingenuous anthropomorphic hypostases of philosophical 'non

entities', for example, the Goddess Nairatmya

Tibetan bdag med ma) is not a principle accepted in lieu of the Hindu

entity, but it is a principle accepted in spite of the Hindu principle, and

arrived at by totally different speculative processes. The Buddhist teachers

must have been aware of the danger of postulating anything that might smack of

the teachings which the Buddha had rejected; I am not persuaded by the rather

facile assumption, shared by many Indian and occidental scholars, that the

later Buddhists had forgotten that the mainstay of Buddhism had been

dismantling the notion of Being and of Self; nor by the oft propounded idea

that an ideological group which keeps up its distinct identity chiefly by

refuting another ideological group gradually assumes the latter's terms and

ideas.

This

may be so among political groups (the Nazis developed a system and a language

which was very similar, in many points, to communism which they fought), but it

is hardly believable about scholars who are critically aware of their

doctrinary differences from the ideology which they oppose. In other words, I

cannot bring myself to believe that Asanga or Advayavajra or any other tantric

Buddhist teacher should have been unaware of the possible charge of 'your sunyata

or your Nairatmya are so thoroughly rarefied that there is no difference left

between them and Brahmin notions of Being'. Samkaracarya was called a crypto Buddhist

(prachanna Buddha) by his Brahmin opponents, because his Brahman was so utterly

rarefied and depersonalized that it reminded the less informed of the assumed

Buddhist nihil, the .sunya. Had any of the famous Buddhist teachers been

charged with being a crypto Hindu, such a charge would have probably been

recorded. As it is, scholastic Hindus feel a strong doctrinary resentment

against Buddhist doctrine, and it is only the Occidentalized, 'all religions are

basically one' Hindus who declare the Buddhist teachings as a form of Hinduism

or vice versa.

The

Buddhist dialectician proceeds from the denial of any entity, from the axiom of

momentariness, and arrives at the notion of s'anya; the Hindu dialectician has

a built in deity as the basis for his speculations on a self, on a static

entity. To the outsider, however, the rarefied Brahman of the Vedanta monists

and the Buddhist sunya may look similar or 'virtually' identical as

intellectual constructs. But they are not. Buddhism has no ontology, no

metaphysics; Hinduism has a powerful ontology this is the one unbridgeable

difference between all of its forms and Buddhism of all schools. That the

psycho experimentalist, the tantric, or anyone who takes sadhana seriously (and

taking scidhana seriously means regarding it as more important, though not

necessarily more interesting, than philosophy), may come to feel that there is

some sort of identity between sunyata and Brahman, is a different matter: it

does not conflict with what is said above, and there is no gainsaying the fact

that reports on the 'feeling' in Vedanta trained enstasis and in tantric

enstasis is very similar indeed.

Yet,

even if two authentic reports on enstatic experience should coincide, it does

not follow from this that the schools from which these reports derive teach a

similar philosophy. The notion upheld among religious teachers in India today

that a specific sadhana yields a specific philosophy or vice versa, I believe

to be wrong; it hails from an understandable pious wish that the corpus of

doctrine, embodied in one tradition, should be autonomous, and should encompass

both sadhana and philosophy. To put this point succinctly: no specific sadhana

follows from any one philosophy, nor does any specific philosophy follow from

any particular sadhana. Our own tantric tradition provides the best

illustration: tantric sadhana follows a single pattern, Vajrayana Buddhist and

Hindu tantric sadhana is indistinct guishable, in spite of the immense

disparity between the two philosophies.

I

admit, however, that the language of Vajrayana suggests ontology to a degree

where a scholar, who did not know Hindu or Buddhist philosophy, but did know

Sanskrit and modern occidental philosophy would be at a loss to realize that

Buddhist philosophy was non ontological as opposed to Hindu philosophy. To

quote a typical passage from a Vajrayaria text: 'of firm essence, unfragmented,

unbreakable, indivisible in character, incombustible, indestructible, sunyata

is vajra (i.e. the Buddhist Void is the Buddhist Adamantine, the Vajra). Word

for word, this description of sunyata and vajra could apply to the brahtnan of

the Veal 16n, and for that of all Hindus, and I do not think there is any

adjective in this passage which has not been applied to the Brahman, with the

exception perhaps of asauirryam (lit. 'un perforated'), which I have not seen

in a Hindu text; 'unbreakable, indivisible, incombustible', almost in this

order, is the description of the infinite Brahman in the Bhagavad-Gita .It is

futile to speculate why the tantric writers availed themselves of terms which

were excessively popular with their Brahmin opponents, in Describing the

ultimate.

I think

the main reason is simply that these terms are ready theological superlatives,

abstract enough for the statement of principles. On the other hand, these

adjectives would be less suggestive of ontology had they not been constantly used

by Hindu, i.e. ontological, thinkers. Without the Hindu reference, these terms

can be used as epithets to non ontological notions just as much as they can for

ontological ones. They may be semantic ally more suggestive of ontological

background, because 'things' arc 'breakable' and 'divisible', etc.; yet such

consideration is somewhat jejune, for after all the ontological notions of

Hinduism, or of any ontological philosophy, as the 'on' of the Elcadic

philosophers, or the 'ens' of Thomism, or 'Being' (das Sein, as opposed to das

Seiende) of Heidegger are not really any of the 'things' which are breakable or

combustible. This is just an illustration of the fact that languages use object

language terms to qualify non object language concepts.

The specific

case of extension of ontological vocabulary to non ontological thought may have

another, somewhat more technical cause: the tantric Buddhist 'commentators had

to vindicate their preceptors' facile use of 'surrounding' terminology: by this

I mean that the first tantric teachers, such as the eighty four siddhas, who

were mostly rustic folk without much liking for and no pretence to learning,

were constantly exposed to Hindu village parlance around them, and popular

Hinduism was hardly distinguishable from popular Buddhism in early medieval

Bengal. Their more learned commentators in turn used learned non Buddhist

vocabulary to denote Buddhist concepts, in conscious analogy, perhaps, to their

unsophisticated preceptors' use of unsophisticated non Buddhist vocabulary. It

is a pattern frequently observed elsewhere: the words of Christ, often

indiscriminately reminiscent of Hellenic pantheistic ideology CI and the Father

are one'), had to be exegetically 'atoned for' by the learned Fathers and

scholastics in later days. St. Augustine's work was one great effort to

eradicate any trace of Hellenic and Alexandrina pantheism and to put dualistic

monotheism on a firm basis. Christ had been exposed to 'surrounding' non Judaic

terminology, the Province of Galilea

Being

suffused by popular Hellenic doctrines largely pantheistic ('What good can come

of Nazareth' John ). In later centuries, we have an exact analogue in the

teachings of Mohammed. The main difficulty for all learned commentators who

write as apologists for their naive preceptors consists in the attempt to make

the learned believe that the preceptors had entertained sophisticated

theological ideas which they chose to put into naive language for the benefit

of the crowd yet no exegete who does not also happen to be an anthropologist

would state the facts as they are: that the founders or the first saintly

preceptors of most religious traditions were naive, and did not teach

discursive theology, not because they did not want to, but because they knew

nothing about its.

Thus,

Bhusukapada, a siddhas listed in all Tibetan histories of Buddhism, seemed to

put a blend of Vijiianavada, Madhyamikas and Vedanta teachings in his saying:

'the great tree of sahaja is shining in the e worlds; everything being of the nature

of sunya, what will bind what? As water mixing with water makes no difference,

so also, the jewel of the mind enters the sky in the oneness of emotion. Where

there is no self, how can there be any non self? What is increate from the

beginning can have neither birth, nor death, nor any kind of existence. Bhusukapada

says: this is the nature of all nothing goes or comes, there is neither

existence nor non existence in sahaja. It is quite evident that once this sort

of poetry, vague in doctrinary content but rich in potential theological

terminology, is accepted as canonical, commentators of any of the philosophical

schools can use it for their specific exegeses.

I think

an analogy in modern times is permissible, because village religion has not

changed very much in India. Thus, the unsophisticated sadhu and his village

audience use and understand terms like atman, Brahman, Maya; for them, these

terms are less loaded than for the specialist, but they are used all the same.

Similarly, .1 think Bhusuka, Kanh, and Saraha, etc., used sunya' and `sahaja'

in this untechnical, but to their rustic audiences perfectly intelligible,

sense; not, again, because of pedagogical prowess and `to make it easy', but

because those preceptors did not have any scholastic training for them; these

terms were as un loaded as for their audience, at least on the discursive

level.

This is

not to deny the possibility that the spiritual experience related to their

sadhana did enhance the charisma of these terms for the adepts.

Now of

all Indian ideologies, tantrism is the most .radically absolutistic, and the

'two truths' coalesce completely; the intuition of this coalescence indeed

constitutes the highest 'philosophical' achievement of the tantric (here I am

using 'philosophical' in the way H. V. Guenther does he translates 'rnal byor' yogi,

by 'philosopher'). Any Tibetan teacher, such as Kham lung pa, 'admitted the

theory of the two truths, according to which the 'All was either conventional

or transcendental'. There is a constant merger of the phenomenal samvrti into

the absolute paramartha, logically because the former has the 'void' sunya as

its basis, and in the experience of the adept, because he dissolves the

phenomenal in sunya, this being the proper aim of all sadhana is; and the frame

of reference wherein the tantric conducts all his sadhana is the complete

identity of the two. Thus the Guhyasamaja, one of the most important and oldest

Buddhist tantric texts, says (the Buddha Vairocana speaking), 'my

"mind" (citta, sems) is such that it is bereft of all phenomenal

existence, "elements" (dhatus) and "bases" (ayatanas) and

of such thought categories as subject and object, it is without beginning and has

the nature of sunya'. There are very few concepts which Hindu and Buddhist

tantrism do not share. The 'three bodies' (trikaya, sku gsurn) doctrine,

however, is uniquely Buddhist and has no parallel in Hindu tantrism.

This, I

think, is the only case where there was a real separation of terminological

spheres: there is nothing like a trikaya' doctrine in Hinduism, although the

Kashmiri Trika' School of Saivism has traces of a threefold division of ‘body’

principles, possibly similar to the Vaisnava notion of the deity in its

threefold aspect as `attraction' (Satnkarsana), `Unrestrainability'

(Aniniddha), and 'the purely mythological' (Damodara). In the Mahayana

classification of the three 'bodies', definitional certainty is by no means

equally strong. Thus, dharma kaya and nirmanakaya (chos kyi sku and sprul sku),

it seems to me, are relatively un complicated notions, but there is a lot of

uncertainty about sambhoga kaya. On the Hindu tantric side, I think that, apart

from those mythological proper names which the Buddhist tantric pantheon does

not share, the only term Buddhist tantric literature avoids is Sakti in its

technical sense, i.e. as the dynamic principle symbolized as the female

counterpart to the static wisdom principle.

Summing

up on tantric philosophy, these arc the points that can be made: Hindu tantrism

and Buddhist tantrism take their entire speculative apparatus from non tantric

absolutist Hindu and Buddhist thought, and although systematized tantrism is even

more eclectic than pretantric ideologies, there is a pretty clear distinction

between Hindu and Buddhist tantric ideas. Common to both is their fundamental

absolutism; their emphasis on a psycho experimental rather than a speculative

approach; and their claim that they provide a shortcut to redemption. The main

speculative difference between Hindu and Buddhist tantrism is the Buddhist

ascription of dynatnicity to the male and of 'wisdom' to the female pole in the

central tantric symbolism, as opposed to the Hindu ascription of dynamicity to

the female and (static) wisdom to the male pole; and lastly, the difference is

terminological inasmuch as certain technical terms very few though are used by

either the Buddhist or the Hindu tantric tradition only. This book presupposes

familiarity with the basic doctrines of Hinduism and Buddhism it is for this

reason that the chapter on tantric philosophy is short and emendatory rather

than a survey. There is really no tantric philosophy apart from Hindu or

Buddhist philosophy, or, to be more specific, from Vedantic and Mahayana

thought.

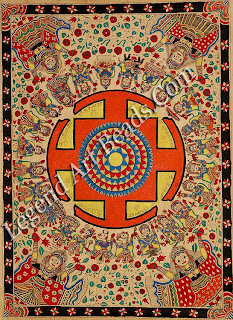

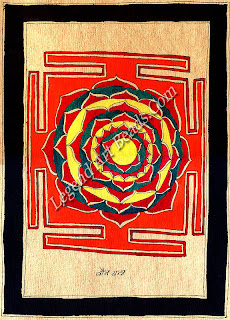

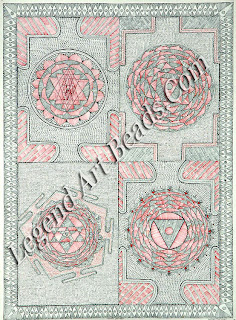

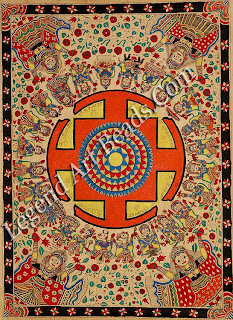

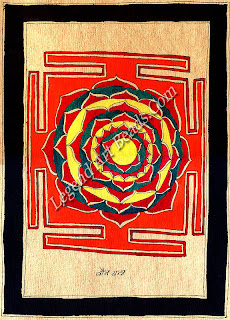

The

diagram which now follows should provide a model for the interrelation of

doctrine and target in the tantric tradition. The late Swami Visvananda Bharati

suggested to Inc that the problem of variant doctrine and common target can be

likened to a 'children's top' (bhramarakridamkam). I found this a helpful

model:

Writer –

Agehananda Bharati

I shall keep cautioning readers about the use of 'philosophy' and

'philosophical' in our context. Historians of western philosophy beginning with

Erdmann and uberweg in the last century, and continuing with virtually all academically

philosophers of the western world up to date have denied Indian thought the

title 'philosophy'. Enologists and oriental scholars, however, have been using

the term for Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain thought quite indiscriminately and this

did not matter too much because there was and there is the assumption that the

twain, professional orient lists and professional philosophers do not meet. I

think this is wrong. It is extremely difficult to make them meet, because a lot

of cross disciplinary studies are needed for both the philosophers will have to

read some original tracts of Indian thought and its paraphrase in other Asian

languages; and the orient lists will have to acquire sonic knowledge of

contemporary philosophy, especially on the terminological side. This has not

been done: scholars who wrote and write on Indian ' philosophers ' Stcherbatsky

, Raju, Glasenapp, Edgerton, Radhakrishnan, to mention but a few did not

seriously attempt to read modern philosophy and use its accurate terminology.

All of them somehow assume that western philosophy had reached its climax with

Kant, Hegel, or Bradley, and hence they do not feel the need to improve on

their archaic terminology. I Think

they are mistaken. Terminologies previous to that of the analytical schools of

twentieth century philosophy are deficient.' It could be objected that

contemporary occidental philosophy may be unequal to the task of providing

adequate terminology for Indian thought patterns; this may be so, but pre twentieth

century occidental philosophy is even less adequate; modern philosophy uses all

the tools of the classical philosophical tradition, plus the considerably

sharper and more sophisticated tools of multi value logic, logical empiricism,

and linguistic analysis.

I shall keep cautioning readers about the use of 'philosophy' and

'philosophical' in our context. Historians of western philosophy beginning with

Erdmann and uberweg in the last century, and continuing with virtually all academically

philosophers of the western world up to date have denied Indian thought the

title 'philosophy'. Enologists and oriental scholars, however, have been using

the term for Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain thought quite indiscriminately and this

did not matter too much because there was and there is the assumption that the

twain, professional orient lists and professional philosophers do not meet. I

think this is wrong. It is extremely difficult to make them meet, because a lot

of cross disciplinary studies are needed for both the philosophers will have to

read some original tracts of Indian thought and its paraphrase in other Asian

languages; and the orient lists will have to acquire sonic knowledge of

contemporary philosophy, especially on the terminological side. This has not

been done: scholars who wrote and write on Indian ' philosophers ' Stcherbatsky

, Raju, Glasenapp, Edgerton, Radhakrishnan, to mention but a few did not

seriously attempt to read modern philosophy and use its accurate terminology.

All of them somehow assume that western philosophy had reached its climax with

Kant, Hegel, or Bradley, and hence they do not feel the need to improve on

their archaic terminology. I Think

they are mistaken. Terminologies previous to that of the analytical schools of

twentieth century philosophy are deficient.' It could be objected that

contemporary occidental philosophy may be unequal to the task of providing

adequate terminology for Indian thought patterns; this may be so, but pre twentieth

century occidental philosophy is even less adequate; modern philosophy uses all

the tools of the classical philosophical tradition, plus the considerably

sharper and more sophisticated tools of multi value logic, logical empiricism,

and linguistic analysis. Than

are modern analytical thinkers; but more importantly, the fact of a system of

thought being closer in emotive tone to another system of thought does not guarantee

that the former is a competent arbiter of the latter. This wrong assumption

goes back to an even older historical phenomenon the great attraction, largely

sentimental, which nineteenth century German classical scholars and poets felt

for things Indian in the belief of a 'kindred sour; this is being echoed in

India by the majority of pandits and holy men: it is very hard to convince

pandits and monks in India that Sanskrit is not taught and spoken in high

schools in Germany, and that Germans are not the only Sanskrit scholars outside

India.

Than

are modern analytical thinkers; but more importantly, the fact of a system of

thought being closer in emotive tone to another system of thought does not guarantee

that the former is a competent arbiter of the latter. This wrong assumption

goes back to an even older historical phenomenon the great attraction, largely

sentimental, which nineteenth century German classical scholars and poets felt

for things Indian in the belief of a 'kindred sour; this is being echoed in

India by the majority of pandits and holy men: it is very hard to convince

pandits and monks in India that Sanskrit is not taught and spoken in high

schools in Germany, and that Germans are not the only Sanskrit scholars outside

India.

0 Response to "The Philosophical Content of Tantra"

Post a Comment