A Year in the Life 1900

A Year in the Life 1900

As France celebrated her imperial prestige with a huge

exhibition in Paris, Europe's colonial powers reaped a bitter harvest abroad.

In Peking, Chinese nationalists rose against the foreigners and in South

Africa, Britain was locked in a vicious struggle with the Boers. The South

African War brought the dawning century two hideous innovations: guerilla

combat and concentration camps.

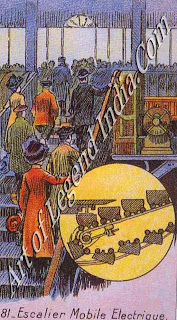

On 14 April 1900, M. Loubet, the President of the French

Republic, opened the greatest international exhibition the world had ever seen.

Total attendance at the Exposition Universelle de Paris, which ran until 11

November, numbered 50 million an average daily attendance of 24,000. Visitors

toured the site on an electrically-powered moving platform with three tiers,

each rolling at a different speed. And for the first time the public saw X-ray

photography, wireless telegraphy and cars.

DELIGHTS OF THE

EAST

In contrast to these technological achievements there was

the exotic exhibition of the colonies, housed near the Eiffel Tower. This

included French colonies and protectorates and those of other nations, though

the term 'colony' was somewhat loosely defined: alongside the Tunisian

pavilion, and those for Madagascar, Algeria, Senegal, the French Congo and

India, were pavilions dedicated to Siberia, Egypt, China and Japan.

In contrast to these technological achievements there was

the exotic exhibition of the colonies, housed near the Eiffel Tower. This

included French colonies and protectorates and those of other nations, though

the term 'colony' was somewhat loosely defined: alongside the Tunisian

pavilion, and those for Madagascar, Algeria, Senegal, the French Congo and

India, were pavilions dedicated to Siberia, Egypt, China and Japan.

Life in the colonies was reconstructed with mosques, temples

and entire villages, to show how the indigenous population might live. There

were Cambodian and Indian dance theatres, a 'diorama' painted with desert

scenes flanked by an Arab quarter where visitors could sample the delights of

North Africa, and a 'stereorama' composed of a revolving circular backdrop

painted to give the impression of travelling by ship along the coast of

Algeria.

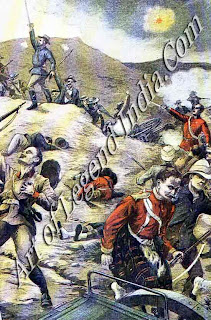

If colonial adventures were a success in Paris, they were a

disaster in London. Since the beginning of the year, the Boer

War in South Africa a bitter struggle between Dutch and

British colonists for control of the Transvaal had cost thousands of lives.

Gold had been discovered there in 1886, transforming the poor agricultural

region farmed by the Boers into one of the wealthiest in Africa, and tension

had mounted steadily. In October 1899, the High Commissioner Sir Alfred Milner

rejected an ultimatum from the Boer leader Paul Kruger to withdraw British

troops.

BRITISH UNDER SIEGE

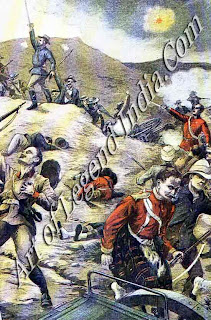

The Boers attacked British positions and in one 'black week'

of December 1899 the three divisions of the British Army under Sir Redvers

Buller (subsequently known as Sir Reverse Buller), were defeated and holed up

in Ladysmith, Kimberley and Mafeking. Boer forces outnumbered their adversaries

by three to one; they were all mounted, familiar with the terrain, and

excellent marksmen armed with German Krupps rifles.

In January, Buller failed disastrously to relieve Ladysmith,

losing 1,700 men at Spion Kop, and Lord Roberts was sent from England to take

overall command. The tide soon turned. Roberts reformed the army and outmaneuvered

General Cronje, the Boer military leader, before relieving Kimberley on 15

February; 12 days later Cronje was forced to surrender. On 28 February,

Buller's fifth attempt to relieve Ladysmith succeeded, and from March until

June Roberts continued his Advance through Bloemfontein, Johannesburg and

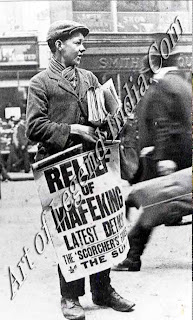

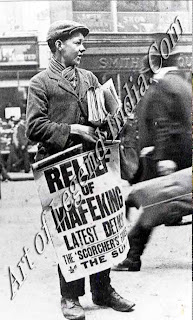

Pretoria. On 17 May, Mafeking was relieved, ending a 215 day siege for Robert

Baden-Powell (founder of the Boy Scout movement) and his soldiers. The Daily

Express, Britain's jingoistic newspaper founded the previous month, blazoned

the news 'History's most heroic defence ends in triumph', and when the news was

announced from the stage in London's theatres, wildly enthusiastic crowds

rushed out to celebrate in the street.

By September the last of the Boer army in the field had been

defeated, all British prisoners of

war had been released, Kruger had fled to

Portuguese territory, and the Transvaal had finally been annexed to Britain.

Roberts handed over command to General Kitchener for what was assumed to be a

simple mopping-up operation. But the war was far from over. In fact, the period

from September 1900 until May 1902 proved the most bitter of all, for it was

the first time a European power experienced a guerilla resistance movement.

Kitchener fought back with a drastic scorched earth policy, even introducing

his notorious 'concentration camps', where rebels including women and children

were coralled in such atrocious conditions that over 20,000 died.

REBELLION IN CHINA

In the autumn, Kruger travelled to Europe to seek help for

the Boers. The continent was generally pro-Boer but even his most likely

supporter, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, refused to see him. Events far away in

China had signalled an urgent need for European co-operation, with the first

stirrings of the 'Boxer' rebellion its name deriving from 'the fist of

righteous harmony'. The rebels were pledged to rid China of foreigners.

In the autumn, Kruger travelled to Europe to seek help for

the Boers. The continent was generally pro-Boer but even his most likely

supporter, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, refused to see him. Events far away in

China had signalled an urgent need for European co-operation, with the first

stirrings of the 'Boxer' rebellion its name deriving from 'the fist of

righteous harmony'. The rebels were pledged to rid China of foreigners.

On 20 June the Boxers had murdered the German consul in

Peking, as a prelude to a siege of foreign legations. In their xenophobic zeal,

they also destroyed much of their own heritage an arson attack on a foreign

warehouse inadvertently burnt the business quarter of Tientsin to the ground,

and also destroyed the Chinese equivalent of the British Museum.

END OF THE MANCHUS

The revolt was short-lived, for in August an international

force, which included American, Japanese and European troops, seized Peking and

hanged the rebels' heads in cages from the city walls. The rising spelt the end

for the Manchu dynasty.

For Europe's royalty too, 1900 was an ominous year. Queen

Victoria was reaching the end of her long reign she died the following year,

aged 82. On 4 April there was an assassination attempt on the Prince of Wales;

on 29 July King Humbert I of Italy was shot dead by an anarchist named Bresci;

and on 16 November a woman threw a hatchet at the German Kaiser, though she

succeeded only in damaging his carriage.

Other developments in Germany were more ominous still. On 6

June the Reichstag passed the Germany Navy Bill a 20 year plan to build 19

battleships, 8 large and 15 small cruisers, at a cost of 861,000,000 marks. And

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin's enormous airship, which was to become such a

dominant feature of the First World War, had its maiden flight, rising to a

height of 1,000 feet with its inventor on board.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

A Year in the Life 1900

A Year in the Life 1900  In contrast to these technological achievements there was

the exotic exhibition of the colonies, housed near the Eiffel Tower. This

included French colonies and protectorates and those of other nations, though

the term 'colony' was somewhat loosely defined: alongside the Tunisian

pavilion, and those for Madagascar, Algeria, Senegal, the French Congo and

India, were pavilions dedicated to Siberia, Egypt, China and Japan.

In contrast to these technological achievements there was

the exotic exhibition of the colonies, housed near the Eiffel Tower. This

included French colonies and protectorates and those of other nations, though

the term 'colony' was somewhat loosely defined: alongside the Tunisian

pavilion, and those for Madagascar, Algeria, Senegal, the French Congo and

India, were pavilions dedicated to Siberia, Egypt, China and Japan.  In the autumn, Kruger travelled to Europe to seek help for

the Boers. The continent was generally pro-Boer but even his most likely

supporter, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, refused to see him. Events far away in

China had signalled an urgent need for European co-operation, with the first

stirrings of the 'Boxer' rebellion its name deriving from 'the fist of

righteous harmony'. The rebels were pledged to rid China of foreigners.

In the autumn, Kruger travelled to Europe to seek help for

the Boers. The continent was generally pro-Boer but even his most likely

supporter, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, refused to see him. Events far away in

China had signalled an urgent need for European co-operation, with the first

stirrings of the 'Boxer' rebellion its name deriving from 'the fist of

righteous harmony'. The rebels were pledged to rid China of foreigners.

0 Response to "French Great Artist Paul C'ezanne - A Year in the Life 1900 "

Post a Comment