Politics of the People

Born of

peasant stock, the political philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon dreamed of

creating a utopian workers' state. But when the revolution came, it brought a

bloodbath, not an earthly paradise.

'In

1848', claimed Courbet long afterwards, 'there were only two men ready: me and

Proudhon.' In that year the people of Paris had risen against the government of

Louis Philippe, only to replace him with Louis-Napoleon, the adventurer nephew

of Bonaparte himself. Implicit in Courbet's boast was a view of himself as a

shrewd and committed revolutionary, whose social ideas were ahead of his time.

But he in fact was no more than a spectator in those turbulent February days.

It was Proudhon alone. Courbet's friend and compatriot from the Jura hills who

could really claim to have anticipated the events and sought to shape them.

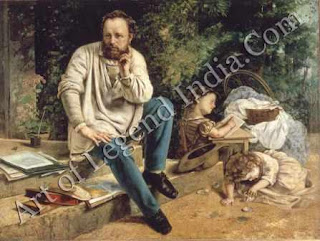

A

founding father of the international anarchist movement, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

had been born in 1809 in the provincial city of Besancon, just a few miles from

Courbet's birthplace at Ornans. Proudhon's parents were both of peasant stock.

His father was a cooper-brewer, his mother a cook, and he himself was

apprenticed to a printer. This trade provided him with his education, for it

was as a corrector of texts that he acquired knowledge of grammar, ancient

languages and theology. His gift for learning so impressed the Academy of

Besancon that in 1838 he was awarded a scholarship, which allowed him to move

to Paris and undertake a regular course of study. But the fruits of this

learning did not please Proudhon's sponsors. In 1840, the year Courbet himself

arrived in Paris, the unruly young printer produced What is Property?, a

sensational tract whose well-known answer 'property is theft' made him famous

overnight.

The

ideas put forward in this and subsequent books reflected Proudhon's

peasant-craftsman background and appealed most to those radical Frenchmen who

had also moved from the countryside to the growing industrial cities.

Proudhon's philosophy, which is often called 'mutualism', sought an economic

solution to the injustices of commercial exploitation. Dismissing the

revolutionary overhaul of the state urged by other radical thinkers, Proudhon

wished to dispense with the state altogether. Instead he called for 'anarchy',

a harmonious society where an

all-powerful, law-enforcing government would be unnecessary.

Proudhon's

perfect society was an idealized version of Besancon and its environs, a

network of small communities of producers who would exchange their surplus

goods for the things they could not produce themselves, aided by a system of

free monetary credit. By cutting out the middleman, this 'mutualist' barter

would eliminate the abuses of property. Proudhon was it advocating self-help

rather than state intervention: for him, big was bad, and he had no time for

revolutionary theories based on parliamentary struggles or the strength of the

masses.

Proudhon's

perfect society was an idealized version of Besancon and its environs, a

network of small communities of producers who would exchange their surplus

goods for the things they could not produce themselves, aided by a system of

free monetary credit. By cutting out the middleman, this 'mutualist' barter

would eliminate the abuses of property. Proudhon was it advocating self-help

rather than state intervention: for him, big was bad, and he had no time for

revolutionary theories based on parliamentary struggles or the strength of the

masses.

In the

early 1840s Proudhon divided his time between a job with a water-transport firm

in Lyon and literary activities in Paris. In the capital, Proudhon was often

found in the Brasserie Andler, where Courbet was also a regular and soon became

a disciple.

THE RADICAL POLITICIAN

In 1847

Proudhon settled down in Paris more permanently in order to devote himself to

his newspaper, Le Representant du Peuple. And despite his well-aired misgivings

about the value of parliamentary struggles he allowed himself to be elected to

the new National Assembly when the monarchy of Louis Philippe was overthrown in

February 1848. Predictably, he took his seat on the far left of this Assembly

and soon identified himself with those militant workers who were agitating for

a radical reconstruction of society. But when Louis-Napoleon seized power,

Proudhon paid for his activities with three years in prison.

In 1847

Proudhon settled down in Paris more permanently in order to devote himself to

his newspaper, Le Representant du Peuple. And despite his well-aired misgivings

about the value of parliamentary struggles he allowed himself to be elected to

the new National Assembly when the monarchy of Louis Philippe was overthrown in

February 1848. Predictably, he took his seat on the far left of this Assembly

and soon identified himself with those militant workers who were agitating for

a radical reconstruction of society. But when Louis-Napoleon seized power,

Proudhon paid for his activities with three years in prison.

Soon

after his release, Proudhon went to live in Belgium, but in 1862 he returned to

Paris. He was now in his fifties, and an acknowledged leader of the French

radicals, but his authority was slight. Many of his most fervent supporters had

rejected his insistence on abstention from parliamentary politics, and several

Proudhonists stood for election in 1863. The master himself fulminated against

such political developments, but in his last years he also found time for

lengthy commentaries upon art. In 1865 he sent regrets to Courbet from his

deathbed for not having completed Du Principes de l' Art (On the Principles of

Art), which he had started as a defence of Courbet's paintings; Proudhon's

literary executors undertook the task of preparing it for posthumous

publication. And Proudhon was overjoyed to see his followers prominent in the

'First International' the Inter-national Workingmen's Association.

The

Association had begun as a combination of stolid British trade unionists, fiercely

anti-intellectual Frenchmen, and an assortment of revolutionary veterans. It

was dominated by Karl Marx, a formidable German Jew of bourgeois background,

whom Proudhon had met briefly in 1844. They had even corresponded for a time.

But their political differences had soon overwhelmed initial comradely

etiquette, especially after Marx responded to Proudhon's The Philosophy of

Poverty with a scathing critique entitled The Poverty of Philosophy.

The

Association had begun as a combination of stolid British trade unionists, fiercely

anti-intellectual Frenchmen, and an assortment of revolutionary veterans. It

was dominated by Karl Marx, a formidable German Jew of bourgeois background,

whom Proudhon had met briefly in 1844. They had even corresponded for a time.

But their political differences had soon overwhelmed initial comradely

etiquette, especially after Marx responded to Proudhon's The Philosophy of

Poverty with a scathing critique entitled The Poverty of Philosophy.

INSTANT REVOLUTION

After

Proudhon's death in 1865, the mantle of leading anarchist fell on Mikhail

Bakunin, a Russian disciple and roaming revolutionary, whose power-base was

among the impoverished peasant watchmakers of the Swiss Jura classic Proudhon

territory. Bakunin was committed to instant revolution: the underprivileged

should rise as one and annihilate capitalism in a single destructive swoop.

Bakunin infuriated Marx, who believed that socialism was only possible as a

development from a fully industrialized capitalist society, and whose patient

strategy was based on industrial workers in the big cities rather than

peasant-craftsmen in small towns and villages. So when Marx found himself

unable to control the First International because of the cloak-and-dagger

machinations of Bakunin, he decided to write it off. In 1872, Marx transferred

its headquarters to New York, allowing it to collapse by 1874.

Meanwhile,

fate dealt a crushing blow to France's revolutionaries with the defeat of the

Paris Commune in 1871. Courbet himself was a wholehearted Communard, just as

Proudhon would have been, and dedicated his energies to this historic attempt

to create an independent, workers' Paris. But the Commune drowned in blood.

After atrocities on both sides, the official French government wrested the

capital from the revolutionaries street by street.

A DREAM OF FREEDOM

In the

traditions of socialism, however, the bravery of the Communards won them the

status of heroes, and Courbet earned a reputation as a true revolutionary

artist. Even Marx, usually so scathing about the anarchist dream of a rapid

transformation of society, acknowledged that 'Working-man's Paris, with its

Commune, will be celebrated for ever as the glorious harbinger of a new

society.' In truth, the accolade belonged less to Courbet than to Pierre-Joseph

Proudhon, the self-taught peasant who founded no party but whose ideas inspired

a lasting dream of freedom.

Writer – Marshall

Cavendish

Proudhon's

perfect society was an idealized version of Besancon and its environs, a

network of small communities of producers who would exchange their surplus

goods for the things they could not produce themselves, aided by a system of

free monetary credit. By cutting out the middleman, this 'mutualist' barter

would eliminate the abuses of property. Proudhon was it advocating self-help

rather than state intervention: for him, big was bad, and he had no time for

revolutionary theories based on parliamentary struggles or the strength of the

masses.

Proudhon's

perfect society was an idealized version of Besancon and its environs, a

network of small communities of producers who would exchange their surplus

goods for the things they could not produce themselves, aided by a system of

free monetary credit. By cutting out the middleman, this 'mutualist' barter

would eliminate the abuses of property. Proudhon was it advocating self-help

rather than state intervention: for him, big was bad, and he had no time for

revolutionary theories based on parliamentary struggles or the strength of the

masses.  In 1847

Proudhon settled down in Paris more permanently in order to devote himself to

his newspaper, Le Representant du Peuple. And despite his well-aired misgivings

about the value of parliamentary struggles he allowed himself to be elected to

the new National Assembly when the monarchy of Louis Philippe was overthrown in

February 1848. Predictably, he took his seat on the far left of this Assembly

and soon identified himself with those militant workers who were agitating for

a radical reconstruction of society. But when Louis-Napoleon seized power,

Proudhon paid for his activities with three years in prison.

In 1847

Proudhon settled down in Paris more permanently in order to devote himself to

his newspaper, Le Representant du Peuple. And despite his well-aired misgivings

about the value of parliamentary struggles he allowed himself to be elected to

the new National Assembly when the monarchy of Louis Philippe was overthrown in

February 1848. Predictably, he took his seat on the far left of this Assembly

and soon identified himself with those militant workers who were agitating for

a radical reconstruction of society. But when Louis-Napoleon seized power,

Proudhon paid for his activities with three years in prison.  The

Association had begun as a combination of stolid British trade unionists, fiercely

anti-intellectual Frenchmen, and an assortment of revolutionary veterans. It

was dominated by Karl Marx, a formidable German Jew of bourgeois background,

whom Proudhon had met briefly in 1844. They had even corresponded for a time.

But their political differences had soon overwhelmed initial comradely

etiquette, especially after Marx responded to Proudhon's The Philosophy of

Poverty with a scathing critique entitled The Poverty of Philosophy.

The

Association had begun as a combination of stolid British trade unionists, fiercely

anti-intellectual Frenchmen, and an assortment of revolutionary veterans. It

was dominated by Karl Marx, a formidable German Jew of bourgeois background,

whom Proudhon had met briefly in 1844. They had even corresponded for a time.

But their political differences had soon overwhelmed initial comradely

etiquette, especially after Marx responded to Proudhon's The Philosophy of

Poverty with a scathing critique entitled The Poverty of Philosophy.

0 Response to "French Great Artist Gustave Courbet - Politics of the People "

Post a Comment