The Eve of Destruction

The Eve of Destruction

Dominated

by obsessions with witches, devils, death and decay, the late Middle Ages was a

period of anxiety and uncertainty when people believed themselves to be on the

brink of destruction.

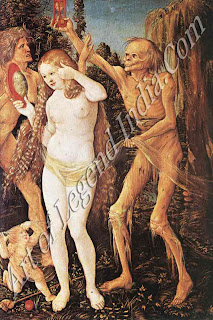

Life in

Europe towards the end of the middle Ages was dominated by a conflict between

the promptings of the flesh and those of the spirit. It was an age of strong

contrasts, a time of passion and violence. Everyday existence was almost casual

in its brutality: lepers walked the streets and public executions were

frequent, often theatrical, and very well attended. The popular imagination was

obsessed with the idea of death the reality of dying rather than the

possibility of heavenly salvation to follow.

It was

generally believed that even Lazarus, after his resurrection, lived in terror

at the thought of having to pass again through the gates of death. And Lazarus

had been one of the just what could an ordinary sinner expect?

Daily

existence was intended to be a preparation for the afterlife, but the reality

was inevitably worldlier. The Church fathers preached that all earthly beauty

and pleasure was sinful, but a common reaction in those uncertain times was

'enjoy yourself as much as you can, while you can'. It was this emphasis on the

demands of the body at the expense of the soul which Bosch attacked. He painted

from the standpoint of orthodox Catholicism he was himself a member of the

Brotherhood of Our Lady with an uncompromising certainty which seems to owe

something to propaganda.

UNGODLY EXAMPLE

People

clearly wanted to be reassured by the authority of the Church, but the clergy

were failing in their duty, as they repeatedly prey to the sins of lust and

greed. Despite the Church ruling of lived openly with women and fathered

children. Their blatant conduct caused great offence. And trust was further

undermined by bands of bogus monks and friars who travelled around selling

false relics and pardons.

People

clearly wanted to be reassured by the authority of the Church, but the clergy

were failing in their duty, as they repeatedly prey to the sins of lust and

greed. Despite the Church ruling of lived openly with women and fathered

children. Their blatant conduct caused great offence. And trust was further

undermined by bands of bogus monks and friars who travelled around selling

false relics and pardons.

Meanwhile,

the more senior officers of the Church led sumptuous and extravagant lives.

Pope Alexander VI, himself a member of the notoriously corrupt Borgia family,

rather hypocritically attempted to enforce a reform bill in 1497 curtailing the

activities of the pleasure-loving Cardinals and restricting their vast

households to a mere 80 strong.

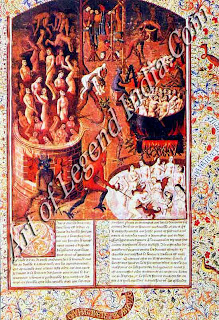

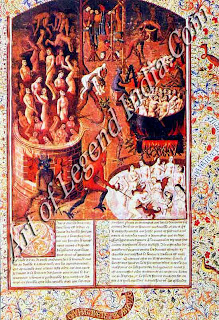

Where

preachers could not convince by godly example and this was the rule rather than

the exception they discouraged sin by stressing the torments of Hell. Sin

provided more opportunities for lavish and inventive imagery than the calm

spiritual grace of a holy life. This morbid fascination accounted for the

success of a book appearing around 1486, the Witches' Hammer, which classified

the many types of witch and described their relations with devils. The demons

in Bosch's paintings were not simply the product of imagination they had a

vivid reality for a superstitious age.

DIVINE VENGEANCE

Revenge

was a part of everyday life, and by extension, if you sinned in this world, God

exacted his own vengeance. But the straightforward notion of the good being

spared and the evil punished was not borne out by events. The Black Death of

1348, for example, had struck down both the righteous and the sinner.

Some

extremists attempted to divert the Divine Wrath by scourging themselves on

processions throughout the countryside. And hysteria of a less religious sort

manifested itself in what became I known as the 'Dancing Mania' groups of

people danced frenziedly in an attempt to find relief from the dreadful fear

that the 'end was nigh'. Against a background of natural disaster, with the

popular imagination inflamed by demons and hellfire, fears of the end of the

world proliferated.

Throughout

the Middle Ages various interpretations were put forward of what would happen

on the Last Day, and when it would occur. In the 1470s in Germany, Hans Bohm,

known as the 'Drummer of Niklashausen', preached that his town was to be the

kingdom of the saved. If you made the pilgrimage to Niklashausen you would

escape destruction, and if you died there you would go straight to Heaven.

Bohm's preaching grew more adventurous as he attacked the clergy and proclaimed

the end of the world. Miracles were attributed to him, and he prophesied a

future kingdom based on true sharing and natural law.

THE RULE OF THE JUST

An

important part in the belief in the imminent apocalypse was the theory of the Millennium.

This was to be the period of 1000 years before the end of the world and the

Last Judgement. The idea had crystallized around the Second Coming of Christ,

who would return for the 'Rule of the Just' when he would rule the world with

his chosen people. The Second Coming would be heralded by the appearance of the

Antichrist, the incarnation of evil, who would make one last bid for world

control before being vanquished forever. The Antichrist and Messiah were most

likely to appear in human form and were constantly expected. Political events

were interpreted with these legendary figures in mind. Chroniclers would

identify a tyrant with the Antichrist or try to make out a new monarch to be

the Last and Just earthly ruler.

The

real disagreements started over the identity g of the chosen people who would

inhabit this earthly paradise, and when such a kingdom would come into being.

The established Church largely followed St Augustine's teaching that the Millenium

had begun when Christ first appeared on the Earth rather than that it would

begin with his Second Coming. This effectively meant that since the world

continued to exist after the year AD 1000, which was when it should have ended

according to the prophecy, then it was possible to suppose that the Rule of the

Just (interpreted as the rule of the Catholic Church) had been extended

indefinitely.

The

real disagreements started over the identity g of the chosen people who would

inhabit this earthly paradise, and when such a kingdom would come into being.

The established Church largely followed St Augustine's teaching that the Millenium

had begun when Christ first appeared on the Earth rather than that it would

begin with his Second Coming. This effectively meant that since the world

continued to exist after the year AD 1000, which was when it should have ended

according to the prophecy, then it was possible to suppose that the Rule of the

Just (interpreted as the rule of the Catholic Church) had been extended

indefinitely.

In this

way Millenarianism was supposedly tamed and converted to the use of the

established Church, but its grip on the popular imagination was too great for

it to perish entirely, and it became an important part of the armoury of

religious reformers and small sects.

There

were times of hardship and social unrest and the idea of 1000 years of earthly

happiness was equally attractive to the body as it was to the soul. Economic

patterns were changing, and with the gradual development of industry the

financial emphasis shifted from countryside to town, and increasingly large

groups of workers were only employed irregularly. It was to such anxious,

insecure and envious people that millenarial prophets, with their promises of a

stable kingdom of the just, especially appealed.

There

were times of hardship and social unrest and the idea of 1000 years of earthly

happiness was equally attractive to the body as it was to the soul. Economic

patterns were changing, and with the gradual development of industry the

financial emphasis shifted from countryside to town, and increasingly large

groups of workers were only employed irregularly. It was to such anxious,

insecure and envious people that millenarial prophets, with their promises of a

stable kingdom of the just, especially appealed.

THE ANABAPTISTS

A

strongly individualized example of this kind of Millenarianism was to be found

among the Anabaptists. In 1533, Anabaptist missionaries appeared in the

Westphalian town of Munster, proclaiming that it was to be the New Jerusalem

the Kingdom of the just. Two leading Anabaptists arrived, Jan Matthys and Jan

Bockelson, who conducted mass baptisms as hundreds entered the new faith. The

Anabaptists believed the Second Coming was imminent and that the Lord's way

would be made easier by getting rid of all non-believers. Consequently,

non-believers were expelled and control of the city was assumed by Matthys who

advocated communal ownership of property and burnt all books except the Bible.

Soon after, however, Matthys was killed by the Bishop of Miinster's besieging

forces, so Bockelson took over and reigned as a new Messiah, with similar ideas

but also encouraging polygamy.

The

citizens of Munster were convinced they were saved and that soon they would

inherit the whole earth. Bockelson conducted a highly effective defensive

campaign against the Bishop of Munster, and set himself up as a prophet king. But

the Bishop's siege continued and the town fell in June 1535 when its food

supplies were exhausted.

The

citizens of Munster were convinced they were saved and that soon they would

inherit the whole earth. Bockelson conducted a highly effective defensive

campaign against the Bishop of Munster, and set himself up as a prophet king. But

the Bishop's siege continued and the town fell in June 1535 when its food

supplies were exhausted.

Although

orthodox Catholic doctrine had attempted to absorb Millenarianism and render it

harmless, it had not succeeded. The Catholic clergy simply could not compete

with the millenarial excitement stirred up by Hans Bohm or the Anabaptists. But

in his paintings, Bosch fervently tried to impart a similar hypnotic vividness

to the hellfire doctrine of the established Church.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

The Eve of Destruction

The Eve of Destruction  People

clearly wanted to be reassured by the authority of the Church, but the clergy

were failing in their duty, as they repeatedly prey to the sins of lust and

greed. Despite the Church ruling of lived openly with women and fathered

children. Their blatant conduct caused great offence. And trust was further

undermined by bands of bogus monks and friars who travelled around selling

false relics and pardons.

People

clearly wanted to be reassured by the authority of the Church, but the clergy

were failing in their duty, as they repeatedly prey to the sins of lust and

greed. Despite the Church ruling of lived openly with women and fathered

children. Their blatant conduct caused great offence. And trust was further

undermined by bands of bogus monks and friars who travelled around selling

false relics and pardons.  The

real disagreements started over the identity g of the chosen people who would

inhabit this earthly paradise, and when such a kingdom would come into being.

The established Church largely followed St Augustine's teaching that the Millenium

had begun when Christ first appeared on the Earth rather than that it would

begin with his Second Coming. This effectively meant that since the world

continued to exist after the year AD 1000, which was when it should have ended

according to the prophecy, then it was possible to suppose that the Rule of the

Just (interpreted as the rule of the Catholic Church) had been extended

indefinitely.

The

real disagreements started over the identity g of the chosen people who would

inhabit this earthly paradise, and when such a kingdom would come into being.

The established Church largely followed St Augustine's teaching that the Millenium

had begun when Christ first appeared on the Earth rather than that it would

begin with his Second Coming. This effectively meant that since the world

continued to exist after the year AD 1000, which was when it should have ended

according to the prophecy, then it was possible to suppose that the Rule of the

Just (interpreted as the rule of the Catholic Church) had been extended

indefinitely.  There

were times of hardship and social unrest and the idea of 1000 years of earthly

happiness was equally attractive to the body as it was to the soul. Economic

patterns were changing, and with the gradual development of industry the

financial emphasis shifted from countryside to town, and increasingly large

groups of workers were only employed irregularly. It was to such anxious,

insecure and envious people that millenarial prophets, with their promises of a

stable kingdom of the just, especially appealed.

There

were times of hardship and social unrest and the idea of 1000 years of earthly

happiness was equally attractive to the body as it was to the soul. Economic

patterns were changing, and with the gradual development of industry the

financial emphasis shifted from countryside to town, and increasingly large

groups of workers were only employed irregularly. It was to such anxious,

insecure and envious people that millenarial prophets, with their promises of a

stable kingdom of the just, especially appealed.  The

citizens of Munster were convinced they were saved and that soon they would

inherit the whole earth. Bockelson conducted a highly effective defensive

campaign against the Bishop of Munster, and set himself up as a prophet king. But

the Bishop's siege continued and the town fell in June 1535 when its food

supplies were exhausted.

The

citizens of Munster were convinced they were saved and that soon they would

inherit the whole earth. Bockelson conducted a highly effective defensive

campaign against the Bishop of Munster, and set himself up as a prophet king. But

the Bishop's siege continued and the town fell in June 1535 when its food

supplies were exhausted.

0 Response to "Netherlandish Great Artist Hieronymus Bosch - The Eve of Destruction "

Post a Comment