Britannia Rules the Waves

For

Turner, there was no more potent symbol of national pride than the magnificent

sailing ships he saw daily on the Thames. They conjured up a world of heroism,

adventure and discovery.

Turner's

lifetime coincided with the golden age of sail. He witnessed not only Nelson's

famous victory at Trafalgar, but also a massive expansion of sea trade with

North America, the West Indies, and the Far East the building of an Empire.

Closer to home, the small coastal and river traders that plied British waters,

delivering passengers and cargo to inaccessible villages all over the country,

were essential for a nation with no effective road or railway system. At the

end of his life, Turner was to see the advent of the steam engine and feel a

mixture of emotions excited by their power, but saddened by the eclipse of the

great sailing ships.

From

his youth in Covent Garden, Turner lived close to the centre of English

commercial shipping. Every day, the Port of London bulged with river traffic.

And with the expansion of British maritime might, London's docks were so

overcrowded that organized pilfering and smuggling became a way of life.

Between July and October the Legal Quays in the Pool of London built in the

15th century were piled eight hogsheads high with sugar, coffee and rum,

presenting an open invitation to the criminal underworld of London's dockland.

From

his youth in Covent Garden, Turner lived close to the centre of English

commercial shipping. Every day, the Port of London bulged with river traffic.

And with the expansion of British maritime might, London's docks were so

overcrowded that organized pilfering and smuggling became a way of life.

Between July and October the Legal Quays in the Pool of London built in the

15th century were piled eight hogsheads high with sugar, coffee and rum,

presenting an open invitation to the criminal underworld of London's dockland.

The

building of new docks, with impounded water and surrounded by high fences to

prevent theft, gave new impetus to maritime commerce in the Port of London.

This development, permitted by an Act of Parliament in 1799, was first

under-taken by the West India Company on the loop of the Thames at the Isle of

Dogs which was, at the time, open country. From the opening of the East India

Docks in 1804-6 the Company, which was run along military lines, enjoyed a

monopoly over trade with the West Indies for over two decades. Likewise, its

bitter rival, the London Dock Company, whose quays at Wapping were opened in

1805, enjoyed a monopoly in the handling of tobacco, wine, rice, brandy and

valuable goods from all parts of the world except the West Indies.

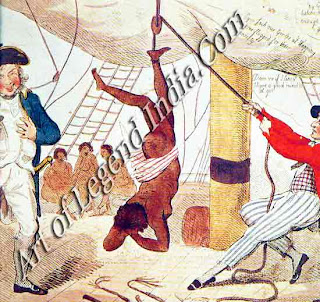

THE SLAVE TRADE

While

the bulk of Britain's maritime business in the late 18th century was conducted

with other European countries, many greedy merchants were engaged in the

'Triangular Trade' which connected Britain with the Guinea Coast in Africa and

the British West Indies across the Atlantic. Slaves were purchased in Africa,

in exchange for metal goods, woven materials, guns and trinkets, then sold to

plantation owners in the West Indies, where the boats were loaded with sugar

and molasses for the return trip to England.

The

slaves were manacled for the journey and stowed tightly on shelves only 30 inches

apart. Three out of eight either committed suicide or died of 'the white flux'

and had to be thrown overboard. While seamen in this lucrative but monstrous

business tended to be, as one captain wrote in 1830, 'the very dregs of the

community', those engaged in commerce with India and China enjoyed a more

respectable and exotic reputation.

The

East India Company, which had dealt exclusively with the Orient since 1601,

bringing silks and tea back to Europe, established a reputation for good crew conditions

and an excellence in de-sign and construction of the ships it chartered. The

East Indiamen large ships of 400 to 500 tons, sometimes armed with more than 30

guns were repaired and fitted out in the Brunswick Dock. By 1820, there were

several of more than twice that size. Because of their enviable reputation,

competition for jobs and berths on these ships was intense.

While

shipping business, ranging from whaling in Greenland to orange running from the

Azores, flourished at Lloyd's underwriters in the City of London, the Royal

Navy had to expand rapidly to protect the territorial interests exploited by

the merchants. Every lawful seafarer came to fear the 'press'. Gangs of

officers and well-built ratings armed with a warrant 'for the impressments of

men' were dispatched into waterfront taverns to kidnap able-bodied fellows.

Whalers, with their reputation for ruggedness and dependability, were favourite

targets, while East India crews tended to enjoy a certain privileged immunity.

Nevertheless, merchant ships, particularly during periods of war, often went to

sea under-manned as a result of press-gang raids.

While

shipping business, ranging from whaling in Greenland to orange running from the

Azores, flourished at Lloyd's underwriters in the City of London, the Royal

Navy had to expand rapidly to protect the territorial interests exploited by

the merchants. Every lawful seafarer came to fear the 'press'. Gangs of

officers and well-built ratings armed with a warrant 'for the impressments of

men' were dispatched into waterfront taverns to kidnap able-bodied fellows.

Whalers, with their reputation for ruggedness and dependability, were favourite

targets, while East India crews tended to enjoy a certain privileged immunity.

Nevertheless, merchant ships, particularly during periods of war, often went to

sea under-manned as a result of press-gang raids.

PIRACY ON THE HIGH SEAS

Privateers

or pirates also represented a direct threat to international traders. It was

quite common for a commission, or 'letters of marque' to be issued by a state

to private vessels, licencing them to plunder merchant shipping of foreign

countries. The French, Dutch, Americans and English all engaged in this

practice and not only were the privateers allowed keeping the spoils of their

plundering, but bonuses were paid by governments for each foreign sailor killed

or taken. This led to ships sailing in convoy and increasing their firepower

for protection.

Privateers

or pirates also represented a direct threat to international traders. It was

quite common for a commission, or 'letters of marque' to be issued by a state

to private vessels, licencing them to plunder merchant shipping of foreign

countries. The French, Dutch, Americans and English all engaged in this

practice and not only were the privateers allowed keeping the spoils of their

plundering, but bonuses were paid by governments for each foreign sailor killed

or taken. This led to ships sailing in convoy and increasing their firepower

for protection.

The

design and construction of British war-ships, ranging from First Rates such as

Nelson's Victory, with up to 120 guns, down to Sixth Rates with 20 guns was

much the same as their merchant counterparts although their crews were usually

larger and occasionally included women in the sick-bays for tending the wounded.

Likewise, while they remained three-masted and square-rigged with mainly oak

woodwork, canvas sails and hemp ropes, they continued to grow in size in the

19th century. The major development in de-sign was seen after 1804 when round

shaped bows and sterns replaced the weaker and much more vulnerable square

bulkhead.

In

later life, when Turner settled in his Thames-side cottage at Cheyne Walk,

Chelsea, he could observe a wide variety of small craft plying the g. river.

The most common boat by far was the smack, a one-masted work-horse which, for

river work, had its bowsprit removed to achieve greater manoeuvrability. Common

on the Thames also was the ranging in size from 12 to 50 tons, which

like the smack carried salt, stone, coal and farm produce along the rivers and

around the shallow coastline. The hoys provided a busy ferry service up and

down the Thames and the seaman's call 'Ahoy' is believed to have originated

from passengers hailing these craft from the river bank.

The first steamboat

appeared on the Thames in 1814 and was an immediate success. Thirteen years

later another steamship crossed the Atlantic for the first time, completing the

journey from Rotterdam to the West Indies in one month. These key events

heralded a battle between sail and steam which continued throughout the

century.

SAIL GIVES WAY TO STEAM

Ironically,

the fierce competition from steam-powered ships, whose speed in adverse weather

gave them a great advantage, inspired sailing ship builders to produce their

finest vessels, such as the famous speedy frigates from the Blackwall Yard in

London, which carried 50 guns and a boudoir for first-class female passengers.

The passing of the leisurely lndiaman was followed by an American innovation in

the form of the clipper whose racy lines helped outlawed slavers, opium traders

and pirates evade capture for several decades, until steamships caught up with

them.

Turner

died in 1851, with the great Yankee clipper perhaps the finest sailing ship

ever in ascendancy. But the commercial lifespan of the ocean-going clipper was

to be short-lived, just as the improvements in roads and the growth of

rail-ways in Britain were rapidly leaving sail-powered smacks and hoys high and

dry.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

From

his youth in Covent Garden, Turner lived close to the centre of English

commercial shipping. Every day, the Port of London bulged with river traffic.

And with the expansion of British maritime might, London's docks were so

overcrowded that organized pilfering and smuggling became a way of life.

Between July and October the Legal Quays in the Pool of London built in the

15th century were piled eight hogsheads high with sugar, coffee and rum,

presenting an open invitation to the criminal underworld of London's dockland.

From

his youth in Covent Garden, Turner lived close to the centre of English

commercial shipping. Every day, the Port of London bulged with river traffic.

And with the expansion of British maritime might, London's docks were so

overcrowded that organized pilfering and smuggling became a way of life.

Between July and October the Legal Quays in the Pool of London built in the

15th century were piled eight hogsheads high with sugar, coffee and rum,

presenting an open invitation to the criminal underworld of London's dockland.  While

shipping business, ranging from whaling in Greenland to orange running from the

Azores, flourished at Lloyd's underwriters in the City of London, the Royal

Navy had to expand rapidly to protect the territorial interests exploited by

the merchants. Every lawful seafarer came to fear the 'press'. Gangs of

officers and well-built ratings armed with a warrant 'for the impressments of

men' were dispatched into waterfront taverns to kidnap able-bodied fellows.

Whalers, with their reputation for ruggedness and dependability, were favourite

targets, while East India crews tended to enjoy a certain privileged immunity.

Nevertheless, merchant ships, particularly during periods of war, often went to

sea under-manned as a result of press-gang raids.

While

shipping business, ranging from whaling in Greenland to orange running from the

Azores, flourished at Lloyd's underwriters in the City of London, the Royal

Navy had to expand rapidly to protect the territorial interests exploited by

the merchants. Every lawful seafarer came to fear the 'press'. Gangs of

officers and well-built ratings armed with a warrant 'for the impressments of

men' were dispatched into waterfront taverns to kidnap able-bodied fellows.

Whalers, with their reputation for ruggedness and dependability, were favourite

targets, while East India crews tended to enjoy a certain privileged immunity.

Nevertheless, merchant ships, particularly during periods of war, often went to

sea under-manned as a result of press-gang raids. Privateers

or pirates also represented a direct threat to international traders. It was

quite common for a commission, or 'letters of marque' to be issued by a state

to private vessels, licencing them to plunder merchant shipping of foreign

countries. The French, Dutch, Americans and English all engaged in this

practice and not only were the privateers allowed keeping the spoils of their

plundering, but bonuses were paid by governments for each foreign sailor killed

or taken. This led to ships sailing in convoy and increasing their firepower

for protection.

Privateers

or pirates also represented a direct threat to international traders. It was

quite common for a commission, or 'letters of marque' to be issued by a state

to private vessels, licencing them to plunder merchant shipping of foreign

countries. The French, Dutch, Americans and English all engaged in this

practice and not only were the privateers allowed keeping the spoils of their

plundering, but bonuses were paid by governments for each foreign sailor killed

or taken. This led to ships sailing in convoy and increasing their firepower

for protection.

Very good website, thank you.

Paper Mache Radha Krishna Wall Hanging

Order Handicrafts Products

Handicrafts Products Online