India's

recorded civilization is one of the longest in the course of world history and

its mythology spans the whole of that time and more. For some periods, indeed,

since Hindu scholarship traditionally has little interest in history as such,

mythology and sacred lore constitute the sole record, and the changes that may

be noted in such traditional materials are thus vital clues to our knowledge of

social and political change. Further-more the mythology is distinguished from

that of most other lands, and certainly those of the West, by the fact that it

is still part of the living culture of every level of society.

The

Indians have always tended to retain their early beliefs and mould them

sometimes perhaps distorting them in such a way as to mirror new social

conditions, to adapt to the customs or beliefs of new rulers, or to fit into a

new philosophical scheme. Over the millennia invaders with superior military

techniques have entered the subcontinent in a steady stream, mostly from the

north-west, and with the exception of the Muslims from the eleventh century

onwards have been assimilated into but at the same time have influenced the

more advanced and deep-rooted culture of the peoples they conquered. Deities

and the myths attached to them have thus multiplied. The major synthesis of the

Aryan or Vedic gods and the native Dravidian deities took shape as the roots of

Hinduism. Because this happened under the guidance of the hereditary class of

priests and philosophers, the Brahmins, it reinforced the status of the

priests, stressing the value of their prerogative, the performance of

sacrifice, in men's relations with the gods.

The

Indians have always tended to retain their early beliefs and mould them

sometimes perhaps distorting them in such a way as to mirror new social

conditions, to adapt to the customs or beliefs of new rulers, or to fit into a

new philosophical scheme. Over the millennia invaders with superior military

techniques have entered the subcontinent in a steady stream, mostly from the

north-west, and with the exception of the Muslims from the eleventh century

onwards have been assimilated into but at the same time have influenced the

more advanced and deep-rooted culture of the peoples they conquered. Deities

and the myths attached to them have thus multiplied. The major synthesis of the

Aryan or Vedic gods and the native Dravidian deities took shape as the roots of

Hinduism. Because this happened under the guidance of the hereditary class of

priests and philosophers, the Brahmins, it reinforced the status of the

priests, stressing the value of their prerogative, the performance of

sacrifice, in men's relations with the gods.

Buddhism

was a reform movement rejecting some of the extremes of the Brahmins' doctrine

and practice. It arose in the fifth century B.C. and held sway among the

educated and powerful in northern India from the time of the Maurya emperor

Ashoka in the third century B.C. until its waning in India in the seventh

century A.D. Though Buddhism and the parallel movement of Jainism were

originally ethical systems whereby the individual through personal effort could

attain union with a universal Absolute beyond all gods, in time they too

acquired mythology and borrowed some of the Hindu and pre-Aryan deities. This

in turn affected classical Hindu mythology and Hindu philosophy of the Golden

Age under the Guptas (fourth to sixth centuries A.D.), which was in part a

defensive reaction to Buddhism. By the ninth century A.D. Hinduism was showing

a tendency to monotheism by putting far greater emphasis on Shiva and Vishnu as

high gods of universal cosmic significance, with worship by bhakti (devotion to

a personal god) rather than by sacrifice performed by priests. After some two

and a half millennia as prime intermediaries with the gods, however, the

priestly caste was by then secure in its preeminence.

Buddhism

was a reform movement rejecting some of the extremes of the Brahmins' doctrine

and practice. It arose in the fifth century B.C. and held sway among the

educated and powerful in northern India from the time of the Maurya emperor

Ashoka in the third century B.C. until its waning in India in the seventh

century A.D. Though Buddhism and the parallel movement of Jainism were

originally ethical systems whereby the individual through personal effort could

attain union with a universal Absolute beyond all gods, in time they too

acquired mythology and borrowed some of the Hindu and pre-Aryan deities. This

in turn affected classical Hindu mythology and Hindu philosophy of the Golden

Age under the Guptas (fourth to sixth centuries A.D.), which was in part a

defensive reaction to Buddhism. By the ninth century A.D. Hinduism was showing

a tendency to monotheism by putting far greater emphasis on Shiva and Vishnu as

high gods of universal cosmic significance, with worship by bhakti (devotion to

a personal god) rather than by sacrifice performed by priests. After some two

and a half millennia as prime intermediaries with the gods, however, the

priestly caste was by then secure in its preeminence.

At

times the influence exerted by the priesthood in India has succeeded, at least

among the educated, in trans-forming the pattern of beliefs. In some cases the

changes advocated were no more than a response to the natural evolution of

India's mythology as a consequence of historical circumstances: dynastic

changes, invasions, economic conditions and the resultant social setting of the

Indian peoples. Thus, for example, the name`asura', originally applied to Aryan

deities such as Varuna, came by the Brahmanic age to refer to demons, albeit

powerful ones. Such changes were particularly apt to alter mythological

beliefs, for Indian myths as well as the religions around which they have grown

up are closely tied to the social structure. It may be said that this is true

of all mythologies but Indian mythology, through its persistence beyond the

primitive levels of civilization and into a highly developed and stratified

culture, has been able, for instance, to reinforce the doctrines of caste, so

that even government disapproval cannot banish it from society.

At

times the influence exerted by the priesthood in India has succeeded, at least

among the educated, in trans-forming the pattern of beliefs. In some cases the

changes advocated were no more than a response to the natural evolution of

India's mythology as a consequence of historical circumstances: dynastic

changes, invasions, economic conditions and the resultant social setting of the

Indian peoples. Thus, for example, the name`asura', originally applied to Aryan

deities such as Varuna, came by the Brahmanic age to refer to demons, albeit

powerful ones. Such changes were particularly apt to alter mythological

beliefs, for Indian myths as well as the religions around which they have grown

up are closely tied to the social structure. It may be said that this is true

of all mythologies but Indian mythology, through its persistence beyond the

primitive levels of civilization and into a highly developed and stratified

culture, has been able, for instance, to reinforce the doctrines of caste, so

that even government disapproval cannot banish it from society.

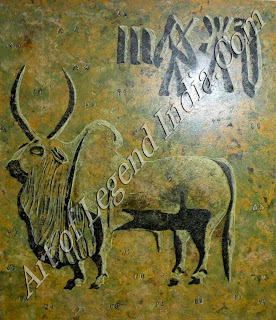

Caste

was first evolved in the late Epic or Brahmanic age, about 800-550 B.C., as the

Aryans expanded over northern India and found it necessary to integrate

majority indigenous populations into their social framework, and it seems from

evidence in the great epics composed in that period that at first change of

caste was possible. The rigidity and complexity of the caste structure as it

developed later seems almost entirely due to Brahmin influence, and through it

Brahmins maintained by right of birth a position as the highest caste. Not all

Brahmins at any time were priests, but nevertheless Brahmin-imposed doctrine

held that each Brahmin had to maintain the purity of the caste as a whole, and

contact with the lower castes, especially as regards food, might pollute and

was strictly regulated.

In

asserting their own status as exclusive repositories of the sacred, and

specifically oral, Vedic traditions that they recited, and as masters of ritual

and sacrifice, sole intermediaries with the gods, Brahmins claimed the right to

respect and to alms. They distanced themselves from the lower castes by

defining the others' functions and duties. Thus the Kshatriya caste among whom

were kings and warriors had the duty of ruling by maintaining efficient and

just administration, conducting warfare to expand and defend the state, and

contracting external alliances; the Vaisya (merchant and artisan) caste had a

duty to further the economic life of society; while the Sudra (peasant or

cultivator) caste was set apart as the lowest caste since its members were not

considered 'twice-born', could not be initiated and so wear the sacred thread,

and were forbidden to study or teach the Vedas, their only permissible contact

with the other castes being as servants. Beyond the castes were the outcastes,

who under-took the menial 'unclean' tasks that polluted the individual; and

beyond all these were the Dravidian aborigines with their tribal gods, who in the

Vedic and Epic ages, until about 600 B.C., were by far the most numerous in the

subcontinent as a whole.

In

asserting their own status as exclusive repositories of the sacred, and

specifically oral, Vedic traditions that they recited, and as masters of ritual

and sacrifice, sole intermediaries with the gods, Brahmins claimed the right to

respect and to alms. They distanced themselves from the lower castes by

defining the others' functions and duties. Thus the Kshatriya caste among whom

were kings and warriors had the duty of ruling by maintaining efficient and

just administration, conducting warfare to expand and defend the state, and

contracting external alliances; the Vaisya (merchant and artisan) caste had a

duty to further the economic life of society; while the Sudra (peasant or

cultivator) caste was set apart as the lowest caste since its members were not

considered 'twice-born', could not be initiated and so wear the sacred thread,

and were forbidden to study or teach the Vedas, their only permissible contact

with the other castes being as servants. Beyond the castes were the outcastes,

who under-took the menial 'unclean' tasks that polluted the individual; and

beyond all these were the Dravidian aborigines with their tribal gods, who in the

Vedic and Epic ages, until about 600 B.C., were by far the most numerous in the

subcontinent as a whole.

Others

of the priests' innovations were inspired by philosophical developments

understood only by the few in general only the priests them-selves but

affecting all. Just as in other cultures, such as those of the ancient Near

East and Egypt, where mythology began by explaining natural phenomena, then

served to bolster the status of the ruler, and finally be-came a symbolic

language expressing the ideas of philosphers, so in India the esoteric cults

treated the great body of accumulated myths as a source of symbols with which

to ex-press philosophical ideas. Inevitably the myths themselves were sometimes

moulded to conform to the ideas that they were made to represent.

Changes

in the social and philosophical backgrounds may be termed the natural causes of

mythological evolution. They were not the only factors; less openly admitted

but of equal importance were the various efforts on the part of the priests to

maintain their own power and influence with the masses by accepting their more

primitive beliefs and dei-ties and weaving them into the new system by means of

myth. Equally the Brahmins consolidated their position of trust with rulers by

securing the allegiance of the people throughout the period when Buddhism was

the faith of the educated and powerful, and when a succession of dynasties,

some foreign, dominated northern and central India (roughly ZOO B.C. to A.D.

800). By the twelfth century the last remaining centres of Buddhist teaching,

the monasteries of Bengal and Bihar in eastern India which had enjoyed the

patronage of the Pala dynasty of the eighth to twelfth centuries, had declined.

With the Turkish Muslim conquest of eastern India soon after f zoo, Buddhism

was con-fined to peripheral countries such as Nepal, Tibet, Assam, Burma, Sri

Lanka and South-East Asia. (A resurgence of interest in Buddhism in its native

India did not occur till the twentieth century, largely among those considered Untouchables

by Hindus.)

Changes

in the social and philosophical backgrounds may be termed the natural causes of

mythological evolution. They were not the only factors; less openly admitted

but of equal importance were the various efforts on the part of the priests to

maintain their own power and influence with the masses by accepting their more

primitive beliefs and dei-ties and weaving them into the new system by means of

myth. Equally the Brahmins consolidated their position of trust with rulers by

securing the allegiance of the people throughout the period when Buddhism was

the faith of the educated and powerful, and when a succession of dynasties,

some foreign, dominated northern and central India (roughly ZOO B.C. to A.D.

800). By the twelfth century the last remaining centres of Buddhist teaching,

the monasteries of Bengal and Bihar in eastern India which had enjoyed the

patronage of the Pala dynasty of the eighth to twelfth centuries, had declined.

With the Turkish Muslim conquest of eastern India soon after f zoo, Buddhism

was con-fined to peripheral countries such as Nepal, Tibet, Assam, Burma, Sri

Lanka and South-East Asia. (A resurgence of interest in Buddhism in its native

India did not occur till the twentieth century, largely among those considered Untouchables

by Hindus.)

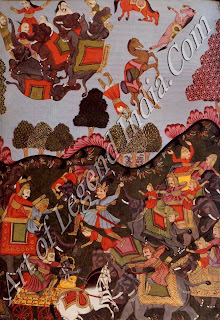

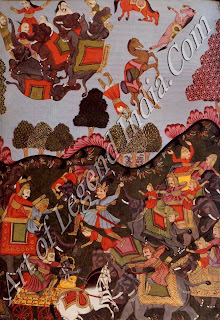

Muslim

incursions into northern India had begun in the early eleventh century and

Mahmud of Ghazni ordered the destruction of Hindu and Jain temple art. Although

effective Muslim rule was not to come until the early thirteenth century and

many shrines were rebuilt, enormous dam-age was done. Nevertheless Hindu

traditions, with the appeal of syncretistic deities, were well enough

established thanks to the Brahmins to survive both in the north and in the

south of India, where Muslim influence reached only much later. Jainism

survived too, largely in Gujerat and southern Rajasthan, where its appeal was

to artisans and to wealthy mercants with the means to patronise it generously;

where necessary it became an underground cult whose artists, turning to easily

concealed manuscript painting, maintained iconographic traditions despite

Muslim rule. Paradoxically Muslim persecution also prompted Hindus to set down

their scriptural traditions in more permanent form. Whereas before they had valued

and relied chiefly on oral tradition a factor which in itself encouraged the

proliferation of mythology now they set down the scriptures in illustrated

manuscripts. The language used was Sanskrit, the classical Aryan language of

the Brahmins (whereas Buddhist texts were also written in a range of vernacular

languages). This reinforced the myths contained within the scriptures.

Muslim

incursions into northern India had begun in the early eleventh century and

Mahmud of Ghazni ordered the destruction of Hindu and Jain temple art. Although

effective Muslim rule was not to come until the early thirteenth century and

many shrines were rebuilt, enormous dam-age was done. Nevertheless Hindu

traditions, with the appeal of syncretistic deities, were well enough

established thanks to the Brahmins to survive both in the north and in the

south of India, where Muslim influence reached only much later. Jainism

survived too, largely in Gujerat and southern Rajasthan, where its appeal was

to artisans and to wealthy mercants with the means to patronise it generously;

where necessary it became an underground cult whose artists, turning to easily

concealed manuscript painting, maintained iconographic traditions despite

Muslim rule. Paradoxically Muslim persecution also prompted Hindus to set down

their scriptural traditions in more permanent form. Whereas before they had valued

and relied chiefly on oral tradition a factor which in itself encouraged the

proliferation of mythology now they set down the scriptures in illustrated

manuscripts. The language used was Sanskrit, the classical Aryan language of

the Brahmins (whereas Buddhist texts were also written in a range of vernacular

languages). This reinforced the myths contained within the scriptures.

That no

one trend was completely dominant is attested by the extreme complexity of

Hindu mythology as it exists today, and even more by the numerous

contradictions and inconsistencies in the stories concerning practically every

deity in the Indian pantheon. There is also a thread of overt anti-Brahmanism

that runs through some myths. It mirrors the reaction voiced in the Upanishads

of the fifth century B.C. and brought to a head by the reform movements of

Buddhism and Jainism against the self-proclaimed superior position of Brahmins,

against caste, deities, ritual, sacrifice, and the doctrine which the Brahmins

put forward of samsara, the transmigration of souls, implying endless rebirth

into a harsh life. Instead of a religious life based on sacrifice that sought

riches, health and long life from the divine power, asceticism or meditation

was advocated, with the aim of detachment from the illusions of worldly life

and union with the cosmic spirit.

Some of

the contradictions and in part the great differences that today exist between

the beliefs held by the educated and the common people may be traced to the

overcomplicated systems evolved. Some of these differences could not be bridged

by mythological ingenuity. The philosophical preoccupations of the Brahmins

with the growing intricacies of their rituals, and on the other hand the heroic

austerities of sages who relied on discipline, not the support of the gods, led

to the exclusion of the common people, who were thus thrown back in some cases

on earlier beliefs, whose attendant ritual had more bearing on their own lives.

There are in India innumerable deities of purely local significance alongside

the great gods. Often they are closely identified with a specific tract of

land, its soil and the life it sustains. Some-times they are worshipped only in

a particular village, or even by a section only of the village, or as domestic

gods. The priests of these village dei-ties are commonly non-Brahmins, and they

may prepare themselves for their priestly role not by purification or

scriptural learning but by trance or possession, thus harking back to the

intoxication sought by early Aryan priests from soma. Their function may often

be to cast out evil spirits causing sickness or misfortune from the sufferer

and transfer them to the deity. Needless to say, myths that may have grown up

about such local deities cannot be covered in a general work. But in fact,

since the position of these local deities is unchallenged by the status of the

great gods of the Hindu pantheon, there has not been the spur to the

elaboration of a mythology to defend them against rival claims of other deities

or to adapt to a changing social order, which is often the background to

developed myths about the major gods.

Some of

the contradictions and in part the great differences that today exist between

the beliefs held by the educated and the common people may be traced to the

overcomplicated systems evolved. Some of these differences could not be bridged

by mythological ingenuity. The philosophical preoccupations of the Brahmins

with the growing intricacies of their rituals, and on the other hand the heroic

austerities of sages who relied on discipline, not the support of the gods, led

to the exclusion of the common people, who were thus thrown back in some cases

on earlier beliefs, whose attendant ritual had more bearing on their own lives.

There are in India innumerable deities of purely local significance alongside

the great gods. Often they are closely identified with a specific tract of

land, its soil and the life it sustains. Some-times they are worshipped only in

a particular village, or even by a section only of the village, or as domestic

gods. The priests of these village dei-ties are commonly non-Brahmins, and they

may prepare themselves for their priestly role not by purification or

scriptural learning but by trance or possession, thus harking back to the

intoxication sought by early Aryan priests from soma. Their function may often

be to cast out evil spirits causing sickness or misfortune from the sufferer

and transfer them to the deity. Needless to say, myths that may have grown up

about such local deities cannot be covered in a general work. But in fact,

since the position of these local deities is unchallenged by the status of the

great gods of the Hindu pantheon, there has not been the spur to the

elaboration of a mythology to defend them against rival claims of other deities

or to adapt to a changing social order, which is often the background to

developed myths about the major gods.

As for

the major gods, the people came to accept new introductions by identifying them

with old gods, and thus reconciling all beliefs. This trend was helped by the

evolving ideas of the Brahmins. The idea of reincarnation, which was unknown to

the Aryan invaders and is never mentioned in the Vedas, appeared about the year

700 B.C. and was developed to the point where any deity, hero, spirit or human

being might be an incarnation of any other. By applying this principle to the

old and the new gods it became possible to claim that the priests were really

worshipping the same deity as the common people under another name and in

another in-carnation or avatar. Alternatively the Brahmins might contrive that

resurgent old traditions or new practices be justified on the basis of their

sup-posed proclamation in the past, preferably by one of the major gods. Thus

the pre-Aryan worship of cobras is incorporated into the Shiva cult in the

Shivala festival of Maharashtra be-cause Shiva is said to have told the people

to worship cobras in order to make them safe. A mythological family

relationship is also introduced: Shiva is said to be the father of the

snake-mother Manasa.

As for

the major gods, the people came to accept new introductions by identifying them

with old gods, and thus reconciling all beliefs. This trend was helped by the

evolving ideas of the Brahmins. The idea of reincarnation, which was unknown to

the Aryan invaders and is never mentioned in the Vedas, appeared about the year

700 B.C. and was developed to the point where any deity, hero, spirit or human

being might be an incarnation of any other. By applying this principle to the

old and the new gods it became possible to claim that the priests were really

worshipping the same deity as the common people under another name and in

another in-carnation or avatar. Alternatively the Brahmins might contrive that

resurgent old traditions or new practices be justified on the basis of their

sup-posed proclamation in the past, preferably by one of the major gods. Thus

the pre-Aryan worship of cobras is incorporated into the Shiva cult in the

Shivala festival of Maharashtra be-cause Shiva is said to have told the people

to worship cobras in order to make them safe. A mythological family

relationship is also introduced: Shiva is said to be the father of the

snake-mother Manasa.

Despite

this apparent confusion and variety, one of the remarkable features of India's

mythology is precisely its homogeneity over the whole country, with the

exception of myths current among the few isolated hill tribes still existing.

And because of the various factors outlined above, the complexity of the

pantheon is common to all. However strictly attached sectarian Hindus may be to

one particular deity, they have always felt the need and ability to fit the

others into their own system. Hence the continued importance of mythology,

which it is best to approach historically.

Writer – Veronica Ions

The

Indians have always tended to retain their early beliefs and mould them

sometimes perhaps distorting them in such a way as to mirror new social

conditions, to adapt to the customs or beliefs of new rulers, or to fit into a

new philosophical scheme. Over the millennia invaders with superior military

techniques have entered the subcontinent in a steady stream, mostly from the

north-west, and with the exception of the Muslims from the eleventh century

onwards have been assimilated into but at the same time have influenced the

more advanced and deep-rooted culture of the peoples they conquered. Deities

and the myths attached to them have thus multiplied. The major synthesis of the

Aryan or Vedic gods and the native Dravidian deities took shape as the roots of

Hinduism. Because this happened under the guidance of the hereditary class of

priests and philosophers, the Brahmins, it reinforced the status of the

priests, stressing the value of their prerogative, the performance of

sacrifice, in men's relations with the gods.

The

Indians have always tended to retain their early beliefs and mould them

sometimes perhaps distorting them in such a way as to mirror new social

conditions, to adapt to the customs or beliefs of new rulers, or to fit into a

new philosophical scheme. Over the millennia invaders with superior military

techniques have entered the subcontinent in a steady stream, mostly from the

north-west, and with the exception of the Muslims from the eleventh century

onwards have been assimilated into but at the same time have influenced the

more advanced and deep-rooted culture of the peoples they conquered. Deities

and the myths attached to them have thus multiplied. The major synthesis of the

Aryan or Vedic gods and the native Dravidian deities took shape as the roots of

Hinduism. Because this happened under the guidance of the hereditary class of

priests and philosophers, the Brahmins, it reinforced the status of the

priests, stressing the value of their prerogative, the performance of

sacrifice, in men's relations with the gods.  Buddhism

was a reform movement rejecting some of the extremes of the Brahmins' doctrine

and practice. It arose in the fifth century B.C. and held sway among the

educated and powerful in northern India from the time of the Maurya emperor

Ashoka in the third century B.C. until its waning in India in the seventh

century A.D. Though Buddhism and the parallel movement of Jainism were

originally ethical systems whereby the individual through personal effort could

attain union with a universal Absolute beyond all gods, in time they too

acquired mythology and borrowed some of the Hindu and pre-Aryan deities. This

in turn affected classical Hindu mythology and Hindu philosophy of the Golden

Age under the Guptas (fourth to sixth centuries A.D.), which was in part a

defensive reaction to Buddhism. By the ninth century A.D. Hinduism was showing

a tendency to monotheism by putting far greater emphasis on Shiva and Vishnu as

high gods of universal cosmic significance, with worship by bhakti (devotion to

a personal god) rather than by sacrifice performed by priests. After some two

and a half millennia as prime intermediaries with the gods, however, the

priestly caste was by then secure in its preeminence.

Buddhism

was a reform movement rejecting some of the extremes of the Brahmins' doctrine

and practice. It arose in the fifth century B.C. and held sway among the

educated and powerful in northern India from the time of the Maurya emperor

Ashoka in the third century B.C. until its waning in India in the seventh

century A.D. Though Buddhism and the parallel movement of Jainism were

originally ethical systems whereby the individual through personal effort could

attain union with a universal Absolute beyond all gods, in time they too

acquired mythology and borrowed some of the Hindu and pre-Aryan deities. This

in turn affected classical Hindu mythology and Hindu philosophy of the Golden

Age under the Guptas (fourth to sixth centuries A.D.), which was in part a

defensive reaction to Buddhism. By the ninth century A.D. Hinduism was showing

a tendency to monotheism by putting far greater emphasis on Shiva and Vishnu as

high gods of universal cosmic significance, with worship by bhakti (devotion to

a personal god) rather than by sacrifice performed by priests. After some two

and a half millennia as prime intermediaries with the gods, however, the

priestly caste was by then secure in its preeminence.  At

times the influence exerted by the priesthood in India has succeeded, at least

among the educated, in trans-forming the pattern of beliefs. In some cases the

changes advocated were no more than a response to the natural evolution of

India's mythology as a consequence of historical circumstances: dynastic

changes, invasions, economic conditions and the resultant social setting of the

Indian peoples. Thus, for example, the name`asura', originally applied to Aryan

deities such as Varuna, came by the Brahmanic age to refer to demons, albeit

powerful ones. Such changes were particularly apt to alter mythological

beliefs, for Indian myths as well as the religions around which they have grown

up are closely tied to the social structure. It may be said that this is true

of all mythologies but Indian mythology, through its persistence beyond the

primitive levels of civilization and into a highly developed and stratified

culture, has been able, for instance, to reinforce the doctrines of caste, so

that even government disapproval cannot banish it from society.

At

times the influence exerted by the priesthood in India has succeeded, at least

among the educated, in trans-forming the pattern of beliefs. In some cases the

changes advocated were no more than a response to the natural evolution of

India's mythology as a consequence of historical circumstances: dynastic

changes, invasions, economic conditions and the resultant social setting of the

Indian peoples. Thus, for example, the name`asura', originally applied to Aryan

deities such as Varuna, came by the Brahmanic age to refer to demons, albeit

powerful ones. Such changes were particularly apt to alter mythological

beliefs, for Indian myths as well as the religions around which they have grown

up are closely tied to the social structure. It may be said that this is true

of all mythologies but Indian mythology, through its persistence beyond the

primitive levels of civilization and into a highly developed and stratified

culture, has been able, for instance, to reinforce the doctrines of caste, so

that even government disapproval cannot banish it from society.  In

asserting their own status as exclusive repositories of the sacred, and

specifically oral, Vedic traditions that they recited, and as masters of ritual

and sacrifice, sole intermediaries with the gods, Brahmins claimed the right to

respect and to alms. They distanced themselves from the lower castes by

defining the others' functions and duties. Thus the Kshatriya caste among whom

were kings and warriors had the duty of ruling by maintaining efficient and

just administration, conducting warfare to expand and defend the state, and

contracting external alliances; the Vaisya (merchant and artisan) caste had a

duty to further the economic life of society; while the Sudra (peasant or

cultivator) caste was set apart as the lowest caste since its members were not

considered 'twice-born', could not be initiated and so wear the sacred thread,

and were forbidden to study or teach the Vedas, their only permissible contact

with the other castes being as servants. Beyond the castes were the outcastes,

who under-took the menial 'unclean' tasks that polluted the individual; and

beyond all these were the Dravidian aborigines with their tribal gods, who in the

Vedic and Epic ages, until about 600 B.C., were by far the most numerous in the

subcontinent as a whole.

In

asserting their own status as exclusive repositories of the sacred, and

specifically oral, Vedic traditions that they recited, and as masters of ritual

and sacrifice, sole intermediaries with the gods, Brahmins claimed the right to

respect and to alms. They distanced themselves from the lower castes by

defining the others' functions and duties. Thus the Kshatriya caste among whom

were kings and warriors had the duty of ruling by maintaining efficient and

just administration, conducting warfare to expand and defend the state, and

contracting external alliances; the Vaisya (merchant and artisan) caste had a

duty to further the economic life of society; while the Sudra (peasant or

cultivator) caste was set apart as the lowest caste since its members were not

considered 'twice-born', could not be initiated and so wear the sacred thread,

and were forbidden to study or teach the Vedas, their only permissible contact

with the other castes being as servants. Beyond the castes were the outcastes,

who under-took the menial 'unclean' tasks that polluted the individual; and

beyond all these were the Dravidian aborigines with their tribal gods, who in the

Vedic and Epic ages, until about 600 B.C., were by far the most numerous in the

subcontinent as a whole.  Changes

in the social and philosophical backgrounds may be termed the natural causes of

mythological evolution. They were not the only factors; less openly admitted

but of equal importance were the various efforts on the part of the priests to

maintain their own power and influence with the masses by accepting their more

primitive beliefs and dei-ties and weaving them into the new system by means of

myth. Equally the Brahmins consolidated their position of trust with rulers by

securing the allegiance of the people throughout the period when Buddhism was

the faith of the educated and powerful, and when a succession of dynasties,

some foreign, dominated northern and central India (roughly ZOO B.C. to A.D.

800). By the twelfth century the last remaining centres of Buddhist teaching,

the monasteries of Bengal and Bihar in eastern India which had enjoyed the

patronage of the Pala dynasty of the eighth to twelfth centuries, had declined.

With the Turkish Muslim conquest of eastern India soon after f zoo, Buddhism

was con-fined to peripheral countries such as Nepal, Tibet, Assam, Burma, Sri

Lanka and South-East Asia. (A resurgence of interest in Buddhism in its native

India did not occur till the twentieth century, largely among those considered Untouchables

by Hindus.)

Changes

in the social and philosophical backgrounds may be termed the natural causes of

mythological evolution. They were not the only factors; less openly admitted

but of equal importance were the various efforts on the part of the priests to

maintain their own power and influence with the masses by accepting their more

primitive beliefs and dei-ties and weaving them into the new system by means of

myth. Equally the Brahmins consolidated their position of trust with rulers by

securing the allegiance of the people throughout the period when Buddhism was

the faith of the educated and powerful, and when a succession of dynasties,

some foreign, dominated northern and central India (roughly ZOO B.C. to A.D.

800). By the twelfth century the last remaining centres of Buddhist teaching,

the monasteries of Bengal and Bihar in eastern India which had enjoyed the

patronage of the Pala dynasty of the eighth to twelfth centuries, had declined.

With the Turkish Muslim conquest of eastern India soon after f zoo, Buddhism

was con-fined to peripheral countries such as Nepal, Tibet, Assam, Burma, Sri

Lanka and South-East Asia. (A resurgence of interest in Buddhism in its native

India did not occur till the twentieth century, largely among those considered Untouchables

by Hindus.)  Muslim

incursions into northern India had begun in the early eleventh century and

Mahmud of Ghazni ordered the destruction of Hindu and Jain temple art. Although

effective Muslim rule was not to come until the early thirteenth century and

many shrines were rebuilt, enormous dam-age was done. Nevertheless Hindu

traditions, with the appeal of syncretistic deities, were well enough

established thanks to the Brahmins to survive both in the north and in the

south of India, where Muslim influence reached only much later. Jainism

survived too, largely in Gujerat and southern Rajasthan, where its appeal was

to artisans and to wealthy mercants with the means to patronise it generously;

where necessary it became an underground cult whose artists, turning to easily

concealed manuscript painting, maintained iconographic traditions despite

Muslim rule. Paradoxically Muslim persecution also prompted Hindus to set down

their scriptural traditions in more permanent form. Whereas before they had valued

and relied chiefly on oral tradition a factor which in itself encouraged the

proliferation of mythology now they set down the scriptures in illustrated

manuscripts. The language used was Sanskrit, the classical Aryan language of

the Brahmins (whereas Buddhist texts were also written in a range of vernacular

languages). This reinforced the myths contained within the scriptures.

Muslim

incursions into northern India had begun in the early eleventh century and

Mahmud of Ghazni ordered the destruction of Hindu and Jain temple art. Although

effective Muslim rule was not to come until the early thirteenth century and

many shrines were rebuilt, enormous dam-age was done. Nevertheless Hindu

traditions, with the appeal of syncretistic deities, were well enough

established thanks to the Brahmins to survive both in the north and in the

south of India, where Muslim influence reached only much later. Jainism

survived too, largely in Gujerat and southern Rajasthan, where its appeal was

to artisans and to wealthy mercants with the means to patronise it generously;

where necessary it became an underground cult whose artists, turning to easily

concealed manuscript painting, maintained iconographic traditions despite

Muslim rule. Paradoxically Muslim persecution also prompted Hindus to set down

their scriptural traditions in more permanent form. Whereas before they had valued

and relied chiefly on oral tradition a factor which in itself encouraged the

proliferation of mythology now they set down the scriptures in illustrated

manuscripts. The language used was Sanskrit, the classical Aryan language of

the Brahmins (whereas Buddhist texts were also written in a range of vernacular

languages). This reinforced the myths contained within the scriptures.  Some of

the contradictions and in part the great differences that today exist between

the beliefs held by the educated and the common people may be traced to the

overcomplicated systems evolved. Some of these differences could not be bridged

by mythological ingenuity. The philosophical preoccupations of the Brahmins

with the growing intricacies of their rituals, and on the other hand the heroic

austerities of sages who relied on discipline, not the support of the gods, led

to the exclusion of the common people, who were thus thrown back in some cases

on earlier beliefs, whose attendant ritual had more bearing on their own lives.

There are in India innumerable deities of purely local significance alongside

the great gods. Often they are closely identified with a specific tract of

land, its soil and the life it sustains. Some-times they are worshipped only in

a particular village, or even by a section only of the village, or as domestic

gods. The priests of these village dei-ties are commonly non-Brahmins, and they

may prepare themselves for their priestly role not by purification or

scriptural learning but by trance or possession, thus harking back to the

intoxication sought by early Aryan priests from soma. Their function may often

be to cast out evil spirits causing sickness or misfortune from the sufferer

and transfer them to the deity. Needless to say, myths that may have grown up

about such local deities cannot be covered in a general work. But in fact,

since the position of these local deities is unchallenged by the status of the

great gods of the Hindu pantheon, there has not been the spur to the

elaboration of a mythology to defend them against rival claims of other deities

or to adapt to a changing social order, which is often the background to

developed myths about the major gods.

Some of

the contradictions and in part the great differences that today exist between

the beliefs held by the educated and the common people may be traced to the

overcomplicated systems evolved. Some of these differences could not be bridged

by mythological ingenuity. The philosophical preoccupations of the Brahmins

with the growing intricacies of their rituals, and on the other hand the heroic

austerities of sages who relied on discipline, not the support of the gods, led

to the exclusion of the common people, who were thus thrown back in some cases

on earlier beliefs, whose attendant ritual had more bearing on their own lives.

There are in India innumerable deities of purely local significance alongside

the great gods. Often they are closely identified with a specific tract of

land, its soil and the life it sustains. Some-times they are worshipped only in

a particular village, or even by a section only of the village, or as domestic

gods. The priests of these village dei-ties are commonly non-Brahmins, and they

may prepare themselves for their priestly role not by purification or

scriptural learning but by trance or possession, thus harking back to the

intoxication sought by early Aryan priests from soma. Their function may often

be to cast out evil spirits causing sickness or misfortune from the sufferer

and transfer them to the deity. Needless to say, myths that may have grown up

about such local deities cannot be covered in a general work. But in fact,

since the position of these local deities is unchallenged by the status of the

great gods of the Hindu pantheon, there has not been the spur to the

elaboration of a mythology to defend them against rival claims of other deities

or to adapt to a changing social order, which is often the background to

developed myths about the major gods.  As for

the major gods, the people came to accept new introductions by identifying them

with old gods, and thus reconciling all beliefs. This trend was helped by the

evolving ideas of the Brahmins. The idea of reincarnation, which was unknown to

the Aryan invaders and is never mentioned in the Vedas, appeared about the year

700 B.C. and was developed to the point where any deity, hero, spirit or human

being might be an incarnation of any other. By applying this principle to the

old and the new gods it became possible to claim that the priests were really

worshipping the same deity as the common people under another name and in

another in-carnation or avatar. Alternatively the Brahmins might contrive that

resurgent old traditions or new practices be justified on the basis of their

sup-posed proclamation in the past, preferably by one of the major gods. Thus

the pre-Aryan worship of cobras is incorporated into the Shiva cult in the

Shivala festival of Maharashtra be-cause Shiva is said to have told the people

to worship cobras in order to make them safe. A mythological family

relationship is also introduced: Shiva is said to be the father of the

snake-mother Manasa.

As for

the major gods, the people came to accept new introductions by identifying them

with old gods, and thus reconciling all beliefs. This trend was helped by the

evolving ideas of the Brahmins. The idea of reincarnation, which was unknown to

the Aryan invaders and is never mentioned in the Vedas, appeared about the year

700 B.C. and was developed to the point where any deity, hero, spirit or human

being might be an incarnation of any other. By applying this principle to the

old and the new gods it became possible to claim that the priests were really

worshipping the same deity as the common people under another name and in

another in-carnation or avatar. Alternatively the Brahmins might contrive that

resurgent old traditions or new practices be justified on the basis of their

sup-posed proclamation in the past, preferably by one of the major gods. Thus

the pre-Aryan worship of cobras is incorporated into the Shiva cult in the

Shivala festival of Maharashtra be-cause Shiva is said to have told the people

to worship cobras in order to make them safe. A mythological family

relationship is also introduced: Shiva is said to be the father of the

snake-mother Manasa.

0 Response to "Religion and History - Indian Mythology"

Post a Comment