Experiments with Perspective

Uccello's

innovative and decorative use of perspective, combined with his flair for

colour, gives his pictures a unique charm that sets them apart from the other

paintings of his time.

In 1481

Cristoforo Landino, a Florentine scholar and philosopher, described Uccello as

a 'good and varied composer, a great master of animals and landscapes and

skilful in foreshortening because he understood perspective well.' Landino was

particularly well-equipped to judge Uccello's painting, for he was a friend and

admirer of Leon Battista Alberti, whose treatise on painting, written in 1435,

contained the earliest account of the principles of linear perspective.

ALBERTI'S SYSTEM

The

principles which Alberti laid down in De Pictura were relatively simple.

Alberti observed that, when we look at the outside world, objects which stand

parallel to our line of vision appear to recede into the distance. Furthermore,

he observed, these parallel lines, or objects, seem to converge towards a

single point somewhere on the horizon. Accordingly, Alberti devised a new

perspective system, known as the costruzione legittima, to show how artists

could reproduce this effect on a flat surface. By constructing the painting

around a grid of converging lines leading to a single 'vanishing point' the

artist could achieve the effect of distance, or recession into space.

The

principles which Alberti laid down in De Pictura were relatively simple.

Alberti observed that, when we look at the outside world, objects which stand

parallel to our line of vision appear to recede into the distance. Furthermore,

he observed, these parallel lines, or objects, seem to converge towards a

single point somewhere on the horizon. Accordingly, Alberti devised a new

perspective system, known as the costruzione legittima, to show how artists

could reproduce this effect on a flat surface. By constructing the painting

around a grid of converging lines leading to a single 'vanishing point' the

artist could achieve the effect of distance, or recession into space.

Uccello

undoubtedly knew about Alberti's ideas, although he was unlikely to have read

De Pictura. During the course of his career he became increasingly interested

in the possibilities of perspective, and exploited it in a number of ingenious

and imaginative ways.

Uccello's

earlier works show little trace of his later fascination with perspective. The

scenes of the Creation and the Fall of Man in the Chiostro Verde (the 'Green

Cloister' in the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence) are constructed in

a shallow foreground space, marked out by the simple shapes of rocks and trees.

Uccello has made no attempt to suggest a deep or dramatic space, but confines

the action to the front of the picture. The frescoes show most clearly the

continued influence on Uccello of his old master Ghiberti, and Uccello may have

worked in part from drawings which Ghiberti was preparing for the second set of

doors for the Baptistry in Florence.

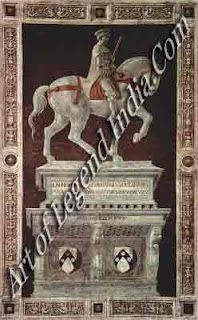

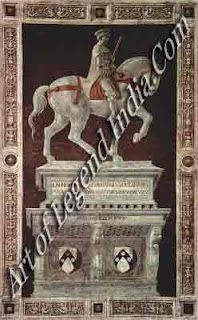

By the

time he came to paint the monument to Sir John Hawkwood however, Uccello had

clearly begun to explore the possibilities of perspective. In this

commemorative fresco he uses perspective to create the illusion of a solid

sarcophagus projecting out from the surface of the wall. Although the horse and

rider seem relatively flat, the sarcophagus itself, when seen in situ, appears

to be three-dimensional.

The

formulation of perspective gave artists an unprecedented freedom in depicting

the external world. For Uccello, however, perspective was not simply a means of

creating an apparently realistic space. He realised that it could also be used

to great dramatic effect. This is the most evident in his late fresco The Flood

in the Chiostro Verde (the 'Green Cloister'). This fresco contains two

different but related episodes the Flood on the left and the Recession of the

Waters on the right. Here, the diagonal lines, or orthogonal, in the picture do

not meet at a single vanishing point as Alberti suggested. Instead, each side

of the picture seems to have its own focal point, a device which divides the

fresco clearly into two. At the same time these two slightly different systems or

'constructions' combine to suggest a dramatic plunge into depth, at the end of

which we see a vivid bolt of lightning. By diverging from the strict

rationality of Alberti's system, Uccello could create a slightly distorted

illusion of space which adds to his terrifying vision of the Flood.

The

formulation of perspective gave artists an unprecedented freedom in depicting

the external world. For Uccello, however, perspective was not simply a means of

creating an apparently realistic space. He realised that it could also be used

to great dramatic effect. This is the most evident in his late fresco The Flood

in the Chiostro Verde (the 'Green Cloister'). This fresco contains two

different but related episodes the Flood on the left and the Recession of the

Waters on the right. Here, the diagonal lines, or orthogonal, in the picture do

not meet at a single vanishing point as Alberti suggested. Instead, each side

of the picture seems to have its own focal point, a device which divides the

fresco clearly into two. At the same time these two slightly different systems or

'constructions' combine to suggest a dramatic plunge into depth, at the end of

which we see a vivid bolt of lightning. By diverging from the strict

rationality of Alberti's system, Uccello could create a slightly distorted

illusion of space which adds to his terrifying vision of the Flood.

CAREFUL DRAWINGS

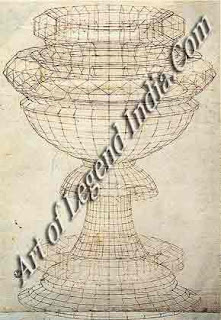

Uccello

did not achieve these effects without careful preparation. For all his frescoes

he used detailed sinopie or under drawings, and in addition it seems likely

that he used cartoons which were pricked through on to the intonaco, the final

layer of plaster. He also made detailed drawings of individual objects seen in

perspective, a few of which have fortunately survived. Some of these may well

have been made for Uccello's own pleasure and instruction but many would have

served as models for use in his paintings.

Uccello

did not achieve these effects without careful preparation. For all his frescoes

he used detailed sinopie or under drawings, and in addition it seems likely

that he used cartoons which were pricked through on to the intonaco, the final

layer of plaster. He also made detailed drawings of individual objects seen in

perspective, a few of which have fortunately survived. Some of these may well

have been made for Uccello's own pleasure and instruction but many would have

served as models for use in his paintings.

These

drawings show particularly clearly how Uccello reduced everything he saw to a

series of geometric shapes. His perspective was not simply a way of

constructing his works. By reducing them to a set of regular forms Uccello

could accommodate figures and objects more easily within the geometric

'construction' and use them to emphasize the underlying grid. By working in

this way, Uccello turned perspective into a kind of decorative scheme. It was

no longer a means of achieving spatial realism, hut a way of creating complex

geometric patterns. It is this imaginative and decorative use of perspective

which makes Uccello's works unique. It sets him apart from the other artists of

his time who were simply using perspective to create the illusion of depth and

three-dimensional reality in a picture.

UNUSUAL COLOURS

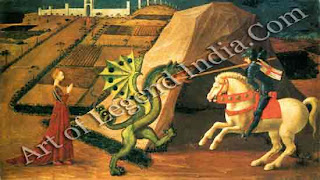

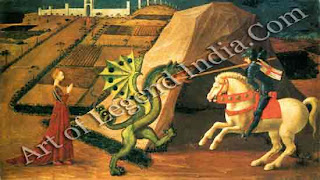

In

Uccello's later works this unusual technique is combined with a superbly

original use of colour. In the battle-pieces which he painted for the Medici,

for example, Uccello uses colour as a way of creating attractive patterns

without aiming to be strictly realistic. Later critics found it hard to

appreciate this aspect of Uccello's style. When describing Uccello's frescoes

at San Miniato, Vasari complained that the artist had 'made the fields blue,

the cities red and the buildings in various colours as he felt inclined.' For

the 15th-century observer, however, this distinctive and witty use of colour

clearly added to the gaiety and charm which gives Uccello's paintings their

lasting appeal.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

The

principles which Alberti laid down in De Pictura were relatively simple.

Alberti observed that, when we look at the outside world, objects which stand

parallel to our line of vision appear to recede into the distance. Furthermore,

he observed, these parallel lines, or objects, seem to converge towards a

single point somewhere on the horizon. Accordingly, Alberti devised a new

perspective system, known as the costruzione legittima, to show how artists

could reproduce this effect on a flat surface. By constructing the painting

around a grid of converging lines leading to a single 'vanishing point' the

artist could achieve the effect of distance, or recession into space.

The

principles which Alberti laid down in De Pictura were relatively simple.

Alberti observed that, when we look at the outside world, objects which stand

parallel to our line of vision appear to recede into the distance. Furthermore,

he observed, these parallel lines, or objects, seem to converge towards a

single point somewhere on the horizon. Accordingly, Alberti devised a new

perspective system, known as the costruzione legittima, to show how artists

could reproduce this effect on a flat surface. By constructing the painting

around a grid of converging lines leading to a single 'vanishing point' the

artist could achieve the effect of distance, or recession into space.  The

formulation of perspective gave artists an unprecedented freedom in depicting

the external world. For Uccello, however, perspective was not simply a means of

creating an apparently realistic space. He realised that it could also be used

to great dramatic effect. This is the most evident in his late fresco The Flood

in the Chiostro Verde (the 'Green Cloister'). This fresco contains two

different but related episodes the Flood on the left and the Recession of the

Waters on the right. Here, the diagonal lines, or orthogonal, in the picture do

not meet at a single vanishing point as Alberti suggested. Instead, each side

of the picture seems to have its own focal point, a device which divides the

fresco clearly into two. At the same time these two slightly different systems or

'constructions' combine to suggest a dramatic plunge into depth, at the end of

which we see a vivid bolt of lightning. By diverging from the strict

rationality of Alberti's system, Uccello could create a slightly distorted

illusion of space which adds to his terrifying vision of the Flood.

The

formulation of perspective gave artists an unprecedented freedom in depicting

the external world. For Uccello, however, perspective was not simply a means of

creating an apparently realistic space. He realised that it could also be used

to great dramatic effect. This is the most evident in his late fresco The Flood

in the Chiostro Verde (the 'Green Cloister'). This fresco contains two

different but related episodes the Flood on the left and the Recession of the

Waters on the right. Here, the diagonal lines, or orthogonal, in the picture do

not meet at a single vanishing point as Alberti suggested. Instead, each side

of the picture seems to have its own focal point, a device which divides the

fresco clearly into two. At the same time these two slightly different systems or

'constructions' combine to suggest a dramatic plunge into depth, at the end of

which we see a vivid bolt of lightning. By diverging from the strict

rationality of Alberti's system, Uccello could create a slightly distorted

illusion of space which adds to his terrifying vision of the Flood.  Uccello

did not achieve these effects without careful preparation. For all his frescoes

he used detailed sinopie or under drawings, and in addition it seems likely

that he used cartoons which were pricked through on to the intonaco, the final

layer of plaster. He also made detailed drawings of individual objects seen in

perspective, a few of which have fortunately survived. Some of these may well

have been made for Uccello's own pleasure and instruction but many would have

served as models for use in his paintings.

Uccello

did not achieve these effects without careful preparation. For all his frescoes

he used detailed sinopie or under drawings, and in addition it seems likely

that he used cartoons which were pricked through on to the intonaco, the final

layer of plaster. He also made detailed drawings of individual objects seen in

perspective, a few of which have fortunately survived. Some of these may well

have been made for Uccello's own pleasure and instruction but many would have

served as models for use in his paintings.

0 Response to "Italian Great Artist Paolo Uccello - Experiments with Perspective "

Post a Comment