A Year in the Life 1848

A Year in the Life 1848

As

Courbet watched the mob mount the barricades in Paris, the shock waves of

revolution reverberated throughout Europe. In Germany and Italy there was a

series of violent uprisings, and in England there were ugly scenes in Trafalgar

Square. Meanwhile, King Louis Philippe had fled France and, more sensationally,

a gigantic sea serpent had been sighted off the African coast.

Everyone

agreed that it was a most dramatic year. Popular writers vied with each other

to find words grand enough to describe it. 'The year 1848', declared one, 'will

be hereafter known as that of the great and general revolt of nations against

their rulers.' A more cynical observer was heartily relieved when it was over.

'One cannot but feel glad,' he noted in his diary, 'at getting rid of a year

which has been so pregnant with every sort of mischief.'

THE COMMUNIST MANIFESTO

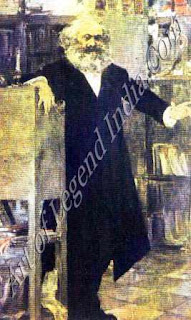

But the

real words of power for 1848 had already been written when the year began and

were in the hands of a London printer. 'Workers of the world, unite!' they ran,

'You have nothing to lose but your chains. You have a world to win.' The

printer's client was a German refugee called Karl Marx and his commission was

The Communist Manifesto.

But the

real words of power for 1848 had already been written when the year began and

were in the hands of a London printer. 'Workers of the world, unite!' they ran,

'You have nothing to lose but your chains. You have a world to win.' The

printer's client was a German refugee called Karl Marx and his commission was

The Communist Manifesto.

The

first rumblings of revolution came from Sicily in January, but they were not

taken very seriously for Sicily was a notoriously volatile and lawless region.

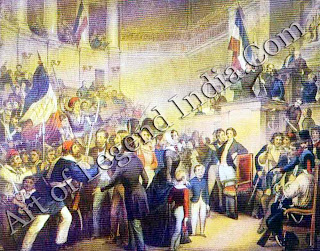

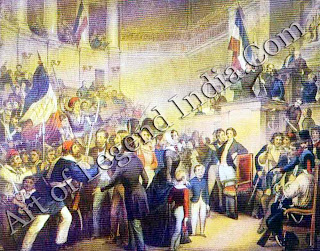

Then on 24 February the moderate middle-class monarchy of King Louis Philippe

in France fell with startling suddenness. In the early hours of the morning,

during a large demonstration outside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Paris,

a man from the crowd walked up to the officer in command of the guard and shot

him dead.

This

had the intended effect of making the soldiers fire on the demonstrators,

several of whom were killed. Their bodies were paraded through the streets in a

cart to the accompaniment of revolutionary songs remembered from the 1790s.

Barricades were set up, some 1,500 altogether, and by daybreak the mob was in

complete control of the city centre.

Louis

Philippe abdicated in favour of his grandson, a boy of 10, but the leaders of

the revolution brushed aside the boy's claims and proclaimed a republic.

Courbet did a drawing of a man at the barricade, to serve as a cover design for

a revolutionary journal. 'Without 1848,' he said later, painting would not have

happened.'

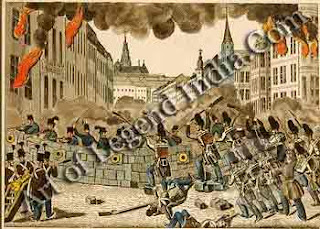

The

first reaction came early in March from Hungary, where nationalist leaders

demanded and obtained concessions from their Austrian rulers in Vienna. Then

there was an uprising in Vienna itself, which forced the Emperor of

Austria-Hungary to grant a new and liberal constitution to his people. The King

of Prussia made similar concessions after an uprising in Berlin which left

hundreds of demonstrators and troops dead. Revolutions followed in other German

kingdoms and a national assembly for the whole of Germany was convened at

Frankfurt, dedicated to sweeping away the existing petty principalities and

creating a united Germany.

UPRISINGS IN ITALY

In

Italy, too, a series of revolutions led to a movement for national unity. After

popular uprisings had driven the Austrian occupying forces out of Milan and

Venice, the King of Sardinia later to be joined by the Grand Duke of Tuscany

embarked on a war to unify the country. The declaration of war came on 24 March.

It had taken just a month for the shock waves from Paris to bring down the

European state system from the Baltic to the southernmost tip of Italy.

In

Italy, too, a series of revolutions led to a movement for national unity. After

popular uprisings had driven the Austrian occupying forces out of Milan and

Venice, the King of Sardinia later to be joined by the Grand Duke of Tuscany

embarked on a war to unify the country. The declaration of war came on 24 March.

It had taken just a month for the shock waves from Paris to bring down the

European state system from the Baltic to the southernmost tip of Italy.

From

all over Europe refugees streamed into Britain, some of them conservatives who

had been toppled and others revolutionaries who had been too extreme. The first

to arrive was Louis Philippe, who landed at Newhaven in the early hours of the

morning on 3 March. He wore a jacket borrowed from the captain of the ship that

had brought him, and he had a week's growth of beard on his face. The Queen was

muffled in a large plaid cloak, with a heavy veil to hide her face.

One Mr.

Stone,' the newspapers reported, 'signalized himself by recognizing the King from

afar off in the boat that brought him ashore.' Mr. Stone welcomed the deposed monarch,

assuring him that the British would protect him from his enemies, and Louis

Philippe, 'much agitated', gave him grateful thanks. The King then took refuge

in coincidence, observing that he had travelled as 'Mr. Smith' and that he now

found the landlady of the inn at which he stayed, as well as the Rector of

Newhaven, had the same reassuring name.

PROTESTS IN TRAFALGAR SQUARE

Three

days later the British had their own first taste of revolutionary activity,

when a certain Mr. Cochrane organized a demonstration in Trafalgar Square to

protest against the income tax. Since only the rich paid the tax, it was not a

very popular cause; and it became even less popular when Cochrane was scared

off by a government ban on the meeting.

His

supporters amused themselves by tearing down the fences around the column being

erected to the memory of Lord Nelson. On the same day there were uglier

troubles further north and cries of 'Vive la Republique!' were heard.

The

authorities took fright and began to enrol special constables to deal with an

enormous demonstration due to take place in London in April, when hundreds of

thousands of radicals would present a petition for the reform of Parliament.

One of the constables was Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, nephew of the Napoleon

Bonaparte who had once sought to invade Britain. He was responsible for the

area between Park Lane and Dover Street, but in the event he had little to do.

The demonstration came to nothing and its petition was rejected.

The

authorities took fright and began to enrol special constables to deal with an

enormous demonstration due to take place in London in April, when hundreds of

thousands of radicals would present a petition for the reform of Parliament.

One of the constables was Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, nephew of the Napoleon

Bonaparte who had once sought to invade Britain. He was responsible for the

area between Park Lane and Dover Street, but in the event he had little to do.

The demonstration came to nothing and its petition was rejected.

In August

there came news sufficiently sensational to crowd out revolutions and radicals.

The officers of a ship sailing off the African coast reported the sighting of a

sea serpent over 100 feet long. Scientists said they were deluded and a fierce

public controversy ensued, in the course of which most of the European

revolutions collapsed without a great deal of attention being paid to them.

In the

autumn Louis-Napoleon slipped across to France and was elected President of the

French Republic. He might have had little to do in London, but in Paris he

meant to maintain law and order. Courbet read the signs and began work on his

great picture The Burial at Ornans. Its real subject, he insisted, was the

death of romantic idealism and the acceptance of reality. The heady days of

1848 were over.

Writer – Marshall

Cavendish

But the

real words of power for 1848 had already been written when the year began and

were in the hands of a London printer. 'Workers of the world, unite!' they ran,

'You have nothing to lose but your chains. You have a world to win.' The

printer's client was a German refugee called Karl Marx and his commission was

The Communist Manifesto.

But the

real words of power for 1848 had already been written when the year began and

were in the hands of a London printer. 'Workers of the world, unite!' they ran,

'You have nothing to lose but your chains. You have a world to win.' The

printer's client was a German refugee called Karl Marx and his commission was

The Communist Manifesto.  In

Italy, too, a series of revolutions led to a movement for national unity. After

popular uprisings had driven the Austrian occupying forces out of Milan and

Venice, the King of Sardinia later to be joined by the Grand Duke of Tuscany

embarked on a war to unify the country. The declaration of war came on 24 March.

It had taken just a month for the shock waves from Paris to bring down the

European state system from the Baltic to the southernmost tip of Italy.

In

Italy, too, a series of revolutions led to a movement for national unity. After

popular uprisings had driven the Austrian occupying forces out of Milan and

Venice, the King of Sardinia later to be joined by the Grand Duke of Tuscany

embarked on a war to unify the country. The declaration of war came on 24 March.

It had taken just a month for the shock waves from Paris to bring down the

European state system from the Baltic to the southernmost tip of Italy.  The

authorities took fright and began to enrol special constables to deal with an

enormous demonstration due to take place in London in April, when hundreds of

thousands of radicals would present a petition for the reform of Parliament.

One of the constables was Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, nephew of the Napoleon

Bonaparte who had once sought to invade Britain. He was responsible for the

area between Park Lane and Dover Street, but in the event he had little to do.

The demonstration came to nothing and its petition was rejected.

The

authorities took fright and began to enrol special constables to deal with an

enormous demonstration due to take place in London in April, when hundreds of

thousands of radicals would present a petition for the reform of Parliament.

One of the constables was Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, nephew of the Napoleon

Bonaparte who had once sought to invade Britain. He was responsible for the

area between Park Lane and Dover Street, but in the event he had little to do.

The demonstration came to nothing and its petition was rejected.

0 Response to "French Great Artist Gustave Courbet - A Year in the Life 1848"

Post a Comment