The Landscape of Provence

Unlike

the Impressionists, who painted numerous scenes of city life, Cezanne never

felt at home in Paris. He returned to his native Provence to find the

inspiration which eluded him in the capital.

Paul

Cezanne began his painting career at a time when the artistic world was firmly

focused on Paris. The early Impressionists all studied there, and even when

they travelled into outlying villages, or to the coast of Normandy, they still

returned repeatedly to the capital to exhibit and attempt to sell their

paintings. But Cezanne, shy and socially inept, was never really suited to

Parisian life. During the eight years he spent there, from 1863 to 1870, he was

happier wandering alone in the hills outside the capital than drinking and

debating with the urbane, avant-garde artists of the Café Guerbois.

THE MOUNTAINS AND THE SEA

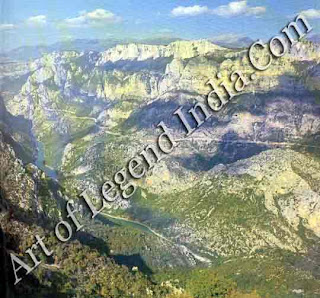

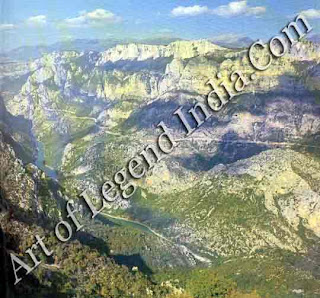

When

the Prussian army invaded France in 1870, Cezanne returned south to his home

town of Aix-en-Provence partly to avoid conscription. The environment he found

there was not only more familiar, but offered an atmosphere totally opposite to

the metropolitan sophistications of Paris. Instead of the grey chill of the

northern winter there was dazzling sunlight and warmth for most of the year;

instead of narrow cobbled streets there were massive granite mountains,

fast-flowing rivers and the blue Mediterranean Sea; instead of jostling crowds

and short-lived fashions there was solitude, a slow pace of life and a

reassuring sense of timelessness.

When

the Prussian army invaded France in 1870, Cezanne returned south to his home

town of Aix-en-Provence partly to avoid conscription. The environment he found

there was not only more familiar, but offered an atmosphere totally opposite to

the metropolitan sophistications of Paris. Instead of the grey chill of the

northern winter there was dazzling sunlight and warmth for most of the year;

instead of narrow cobbled streets there were massive granite mountains,

fast-flowing rivers and the blue Mediterranean Sea; instead of jostling crowds

and short-lived fashions there was solitude, a slow pace of life and a

reassuring sense of timelessness.

The

landscape of Provence became one of the principal inspirations of Cezanne's

work. He painted it with a relentless intensity that few artists have devoted

to any subject, creating dozens of images of favourite motifs, above all the

Mont Sainte-Victoire. In 1886 he wrote to the collector Victor Chocquet, 'there

are treasures to be taken away from this country, which has not yet found an

interpreter equal to the abundance of riches which it displays', and 30 years

later, a few weeks before his death, he was still so entranced with the

landscape that he wrote to his son: 'I think I could occupy myself for months

without changing my place, simply bending a little more to left or right.' Yet

the hundreds of paintings and drawings Cezanne produced of Provence tell us

little about the region. He concentrated on the underlying, unchanging

structure of the landscape, and did not usually represent a particular time of

day or even a particular season. There is nothing anecdotal about his pictures

and they usually contain no figures or other evidence of human activity. Houses

are often included, but they are treated as part of the landscape, and he never

painted the town of Aix itself.

AN INDEPENDENT PEOPLE

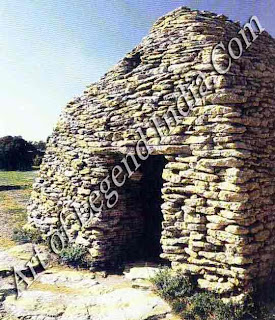

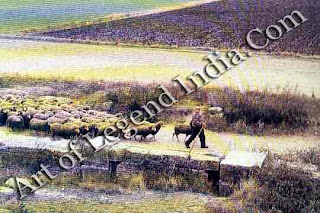

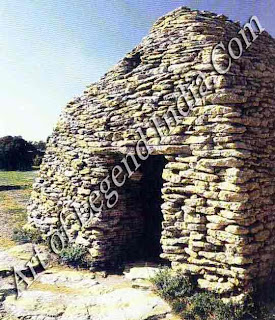

Some

400 miles from Paris, isolated from the north by the Alps and the rugged

plateau of the Massif Central, Provence was like a separate country in

Cezanne's day. Rail links with the north, only recently completed, had done

little to break down an attitude of sturdy independence that dated back to Roman

times, when the region first earned its name as 'Provincia Romana'. Nor had the

lifestyle of its inhabitants changed greatly over the centuries a description

by the Roman fl historian Posidonius remained as true in the 19th century as

the day it was written in the 1st century BC: The country is wild and arid. The

soil is so stony that you cannot plant anything without striking a rock.' The

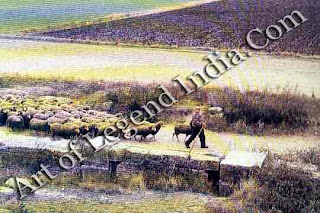

population had remained largely rural, with peasant agriculture the mainstay of

the economy.

Some

400 miles from Paris, isolated from the north by the Alps and the rugged

plateau of the Massif Central, Provence was like a separate country in

Cezanne's day. Rail links with the north, only recently completed, had done

little to break down an attitude of sturdy independence that dated back to Roman

times, when the region first earned its name as 'Provincia Romana'. Nor had the

lifestyle of its inhabitants changed greatly over the centuries a description

by the Roman fl historian Posidonius remained as true in the 19th century as

the day it was written in the 1st century BC: The country is wild and arid. The

soil is so stony that you cannot plant anything without striking a rock.' The

population had remained largely rural, with peasant agriculture the mainstay of

the economy.

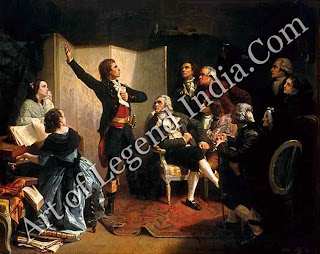

Provence's

stormy history had, if anything strengthened its differences from the rest of

France. After the Romans, the Barbarians, Franks, Saracens and Normans all left

their bloody mark upon the region, attracted by its strategic position between

Spain and Italy at the mouth of the River Rhone. Right up until the time of the

French Revolution it was rare for Provence to enjoy long periods of peace or

stability. But the Revolution was welcomed by the southerners, who believed it

would lead to more independence from the 'Parigots', as they contemptuously

called those from the capital. It was in Marseilles that the French national

anthem the Marseillaise first rang out in 1792. Three years before, the red,

white and blue national flag known as the tricolour was raised in the small

Provencal town of Meringues.

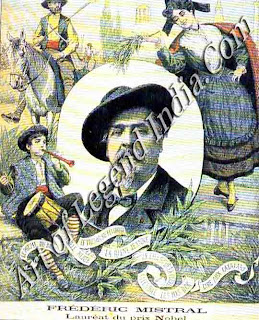

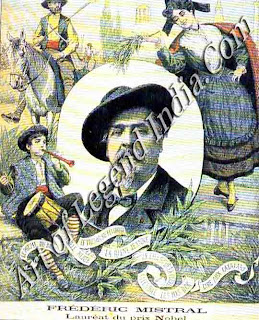

Even in

Cezanne’s time, the inhabitants of Provence maintained a strong sense of

regional pride, underpinned by the local dialect, impenetrable to outsiders.

Cezanne sometimes used it in the Café Guerbois when he wished to be pointedly

anti-social. However, this traditional language was diminishing in use, as the

'standard' Parisian dialect became obligatory for those engaged in commerce. To

try to stop the decline, a poet called Frederic Mistral, with seven other

Provencal literary figures, formed a society in 1854 'to rise up, honour and

defend the mother tongue, now so sadly despised and neglected'. The campaign

was enthusiastically received and the society's review L' Armana Prouvencau

(the Provencal Almanac) became fashionable reading, but it could not reverse

the steady decline in everyday use of the language.

Although

time seemed to have stood still in many parts of Cezanne's Provence, changes

were occurring on the coast that was to transform the region's image, as the

Riviera became a luxurious holiday playground. The fashion for staying there

was started by Lord Brougham, Lord Chancellor of England, who had to stay in

Cannes in 1834 during a cholera outbreak which delayed his intended journey

into Italy. He liked it so much that he returned regularly for the next 30

years. Monte Carlo became probably the most famous of the resorts associated

with conspicuous high-living, and its celebrated casino opened in 1861.

A HAVEN FOR ARTISTS

Although

the railway linked Aix with Cannes and Nice, Cezanne was more attracted to the

coastline nearer home especially the village of L'Estaque, of which he painted

some memorable pictures. The scenery around L'Estaque was renowned for its

beauty, as Zola's description testifies: 'A village just outside of Marseilles,

in the centre of an alley of rocks which close the bay. . . The country is

superb. The arms of rock stretch out on either side of the gulf, while the

islands, extending in width, seem to bar the horizon, and the sea is but a vast

basin, a lake of brilliant blue when the weather is fine.

Although

Cezanne was the first painter to make the Provencal landscape a major subject

of his work, he was not the only great artist of his period to be attracted to

the region. Van Gogh lived at Arles from 1888 to 1890, and was visited .f there

by Gauguin in 1888. Van Gogh had intended forming an artists' colony at Arles,

and although this came to nothing, the fact that he and the other two founding

figures of modern art worked in Provence has, from the early 20th century,

played a part in luring other artists there. Most of the major figures who have

worked there have been drawn to the Cote d'Azur in the east of the region.

Matisse is particularly associated with Nice, and Picasso with Antibes; Renoir

built a villa at Cagnes towards the end of his long life.

Although

Cezanne was the first painter to make the Provencal landscape a major subject

of his work, he was not the only great artist of his period to be attracted to

the region. Van Gogh lived at Arles from 1888 to 1890, and was visited .f there

by Gauguin in 1888. Van Gogh had intended forming an artists' colony at Arles,

and although this came to nothing, the fact that he and the other two founding

figures of modern art worked in Provence has, from the early 20th century,

played a part in luring other artists there. Most of the major figures who have

worked there have been drawn to the Cote d'Azur in the east of the region.

Matisse is particularly associated with Nice, and Picasso with Antibes; Renoir

built a villa at Cagnes towards the end of his long life.

Provence

today is proud of its artistic heritage. Antibes has a Picasso museum, for

example, and Nice has museums devoted to both Chagall and Matisse. Yet the home

town of Provence's greatest artist cannot boast any important examples of his

work. Cezanne's studio in Aix (in a street that has been renamed the Avenue

Paul Cezanne) is open to the public, but the Musk. Granet in Aix has only a few

minor paintings and drawings among its predominantly classical collection of

paintings from the 16th to the 19th centuries. The director in Cezanne's day

was an arch-conservative who vowed that no Cezanne would ever hang there so

long as he had power to prevent it.

Auguste

Henri Pointier kept his word until his death in 1926, by which time Cezanne's

master-pieces had been dispersed around the globe. Yet in one way this is not

inappropriate, for Cezanne was committed to the enduring and universal values

of his landscape rather than its topographical details. His genius belongs to

the world, not just one particular place.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

When

the Prussian army invaded France in 1870, Cezanne returned south to his home

town of Aix-en-Provence partly to avoid conscription. The environment he found

there was not only more familiar, but offered an atmosphere totally opposite to

the metropolitan sophistications of Paris. Instead of the grey chill of the

northern winter there was dazzling sunlight and warmth for most of the year;

instead of narrow cobbled streets there were massive granite mountains,

fast-flowing rivers and the blue Mediterranean Sea; instead of jostling crowds

and short-lived fashions there was solitude, a slow pace of life and a

reassuring sense of timelessness.

When

the Prussian army invaded France in 1870, Cezanne returned south to his home

town of Aix-en-Provence partly to avoid conscription. The environment he found

there was not only more familiar, but offered an atmosphere totally opposite to

the metropolitan sophistications of Paris. Instead of the grey chill of the

northern winter there was dazzling sunlight and warmth for most of the year;

instead of narrow cobbled streets there were massive granite mountains,

fast-flowing rivers and the blue Mediterranean Sea; instead of jostling crowds

and short-lived fashions there was solitude, a slow pace of life and a

reassuring sense of timelessness.  Some

400 miles from Paris, isolated from the north by the Alps and the rugged

plateau of the Massif Central, Provence was like a separate country in

Cezanne's day. Rail links with the north, only recently completed, had done

little to break down an attitude of sturdy independence that dated back to Roman

times, when the region first earned its name as 'Provincia Romana'. Nor had the

lifestyle of its inhabitants changed greatly over the centuries a description

by the Roman fl historian Posidonius remained as true in the 19th century as

the day it was written in the 1st century BC: The country is wild and arid. The

soil is so stony that you cannot plant anything without striking a rock.' The

population had remained largely rural, with peasant agriculture the mainstay of

the economy.

Some

400 miles from Paris, isolated from the north by the Alps and the rugged

plateau of the Massif Central, Provence was like a separate country in

Cezanne's day. Rail links with the north, only recently completed, had done

little to break down an attitude of sturdy independence that dated back to Roman

times, when the region first earned its name as 'Provincia Romana'. Nor had the

lifestyle of its inhabitants changed greatly over the centuries a description

by the Roman fl historian Posidonius remained as true in the 19th century as

the day it was written in the 1st century BC: The country is wild and arid. The

soil is so stony that you cannot plant anything without striking a rock.' The

population had remained largely rural, with peasant agriculture the mainstay of

the economy.  Although

Cezanne was the first painter to make the Provencal landscape a major subject

of his work, he was not the only great artist of his period to be attracted to

the region. Van Gogh lived at Arles from 1888 to 1890, and was visited .f there

by Gauguin in 1888. Van Gogh had intended forming an artists' colony at Arles,

and although this came to nothing, the fact that he and the other two founding

figures of modern art worked in Provence has, from the early 20th century,

played a part in luring other artists there. Most of the major figures who have

worked there have been drawn to the Cote d'Azur in the east of the region.

Matisse is particularly associated with Nice, and Picasso with Antibes; Renoir

built a villa at Cagnes towards the end of his long life.

Although

Cezanne was the first painter to make the Provencal landscape a major subject

of his work, he was not the only great artist of his period to be attracted to

the region. Van Gogh lived at Arles from 1888 to 1890, and was visited .f there

by Gauguin in 1888. Van Gogh had intended forming an artists' colony at Arles,

and although this came to nothing, the fact that he and the other two founding

figures of modern art worked in Provence has, from the early 20th century,

played a part in luring other artists there. Most of the major figures who have

worked there have been drawn to the Cote d'Azur in the east of the region.

Matisse is particularly associated with Nice, and Picasso with Antibes; Renoir

built a villa at Cagnes towards the end of his long life.

0 Response to "French Great Artist Paul C'ezanne - The Landscape of Provence "

Post a Comment