Annibale

Carracci – Italian Great Artist

Annibale

Carracci was the most brilliant member of a family of artists who played an

outstanding part in the revival of Italian painting at the end of the 16th

century. To combat the prevailing artificiality of Italian ad, Annibale,

together with his brother and cousin, founded an academy in his native Bologna.

Their teaching bore fruit in the work of some of the finest artists of the next

generation who studied there.

When he

was 35, Annibale left Bologna for Rome, where he undertook his greatest work the

superb fresco decoration of the Farnese Gallery, which was hailed as the

successor to the masterworks of Michelangelo and Raphael. Annibale was a

warm-hearted and popular man, totally absorbed in his art, but he had a streak

of melancholia in him and in the last five years of his life he succumbed to a

depressive illness.

THE ANNIBALE CARRACCI'S LIFE

The Kindly Melancholic

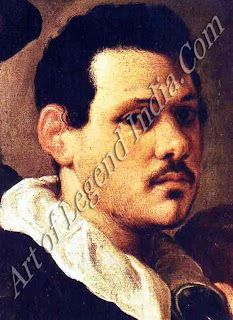

Annibale

was the outstanding artist of the Carracci family. He combined intellect with a

great sense of fun but in later life suffered debilitating periods of illness

and depression.

Annibale

was the outstanding artist of the Carracci family. He combined intellect with a

great sense of fun but in later life suffered debilitating periods of illness

and depression.

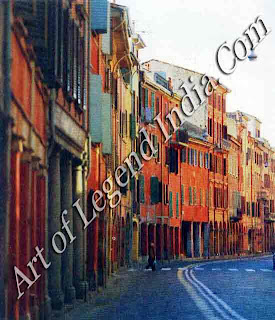

There

have been many outstanding families of painters in the long history of Italian

art, but none more remarkable than the Carracci family of Bologna, who

transformed their native city from something of an artistic backwater to the

centre of the most distinctive tradition in 17th-century Italian painting.

Annibale and Agostino Carracci were brothers and Ludovico Carracci was their

cousin. They were born within five years of each other and in their early

careers worked closely together, but Annibale eventually emerged as the great

genius of the family.

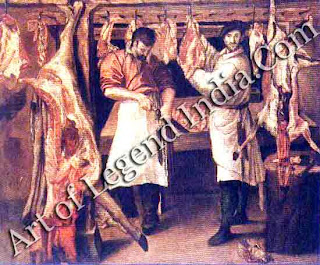

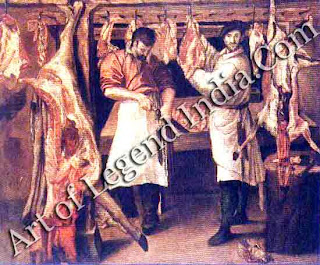

Annibale

was born in the city of Bologna in 1560; he was three years younger than his

brother Agostino. They came from a fairly humble family (their father was a

tailor), while their cousin Ludovico (born in 1555) was the son of a butcher.

We know

little about Annibale's early life, and the two main sources of information on

him, both published by Italian biographers in the 1670s, are in disagreement

about his initial training: Carlo Malvasia says that Annibale learned the

tailor's trade in his father's shop, whereas Giovanni Pietro Bellori asserts

that Annibale was 'placed in the goldsmith's craft'. However, they both agree

that Annibale later trained with his older cousin Ludovico, although the style

of his early work suggests that at some time he probably worked in the studio

of the Bolognese painter Bartolomeo Passerotti (1529-92).

A USEFUL SKILL

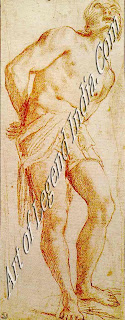

Throughout

his career Annibale was to show prodigious skill as a draughtsman, and Bellori

tells a story that shows this was true even in his early years. 'His father,

Antonio, on returning to Bologna from a trip to Cremona, was robbed by peasants

with the loss of the modest sum he was bringing back. Annibale, who was with

his father, was able to sketch the appearance of those rapacious ruffians so

realistically and accurately that they were recognized by everyone with

astonishment, and what had been stolen from his father was easily recovered.'

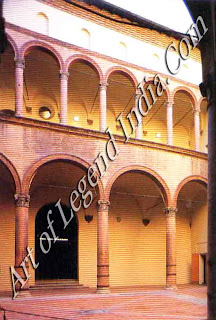

Annibale

probably became an assistant (or perhaps a junior partner) in Ludovico's

workshop around 1580, and all three Carracci were working together by 1584,

when they collaborated on a series of mythological frescoes in the Palazzo Fava

in Bologna. At this stage of their career it was - and still is difficult to

distinguish between their hands, and Malvasia writes that when they were asked

to explain who was responsible for the different parts of another joint venture

a fresco cycle in the Palazzo Magnani in Bologna they replied: 'It is by the

Carracci - we have all made it.'

Annibale

probably became an assistant (or perhaps a junior partner) in Ludovico's

workshop around 1580, and all three Carracci were working together by 1584,

when they collaborated on a series of mythological frescoes in the Palazzo Fava

in Bologna. At this stage of their career it was - and still is difficult to

distinguish between their hands, and Malvasia writes that when they were asked

to explain who was responsible for the different parts of another joint venture

a fresco cycle in the Palazzo Magnani in Bologna they replied: 'It is by the

Carracci - we have all made it.'

The

Carracci collaborated not only on paintings, but also in setting up a teaching

academy, probably in 1582. It was known originally as the Accademia dei

Desiderosi (the Academy of those desirous of fame and learning), and later

changed its name to the Accademia degli lncamminati (which may be translated as

the Academy of the Progressives), and aimed to revitalize what the Carracci

considered to be the moribund state of Italian painting.

Key Dates

1560 born in Bologna

C.1580 enters cousin

Ludovico's workshop

C.1582 founds Academy with his

brother Agostino and cousin Ludovico

1584 the Carracci's first fresco

collaboration

C.1585 visits Parma

C.1587 visits Venice

1595 moves to Rome

1597 begins decoration of Farnese

Gallery

1601 paints altar-piece for

Cerasi Chapel

1604 completes Farnese

Gallery

C.1604 paints landscapes for

the Palazzo Aldobrandini chapel

1605 onset of illness

1609 dies in Rome - buried in

Pantheon

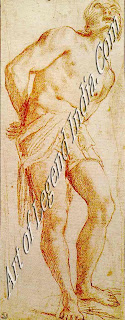

The

basis of the Carracci approach towards a more solid and naturalistic kind of

art was drawing from the life (the artists against whom they reacted took other

paintings, rather than nature, as their models). The artists who studied in the

Academy benefited greatly from this devotion to drawing particularly of the

human figure and clear firm draughtsmanship became one of the hallmarks of the

Bolognese School of painting. Domenichino (Annibale's favourite pupil) and

Guido Reni were the two most famous painters who trained with the Carracci.

PARIVLA AND VENICE

Annibale

strove to cultivate his skills not only by ceaseless drawing but also by

studying the great masters of the recent past. At some time in the 1580s

(probably around 1585), he went with Agostino to Parma, where he was greatly

impressed with the paintings of Correggio, who had worked there in the 1520s

and 1530s. Perhaps a year or so later (again the date is uncertain) Annibale

went to Venice, where he studied the work of Titian and met Tintoretto and

Veronese, the two contemporary giants of Venetian painting. He also met another

distinguished artist, Jacopo Bassano, who was evidently a man after Annibale's

own heart in that he was a keen observer of everyday life.

Annibale's

first dated painting is a Crucifixion with Saints of 1583 in the church of S.M.

Della Carib, Bologna, and during the next 12 years he painted a series of grand

altarpieces in which he revealed himself as an artist of commanding stature.

But the great turning point in Annibale's life came in 1595, when he was 35. In

that year he went to Rome to carry out decorations for Cardinal Odoardo Farnese

in his family palace, and this great commission gave Annibale his first real

opportunity to display his full powers. He lived in Rome for the rest of his

life and was never to see Bologna again.

Annibale's

first dated painting is a Crucifixion with Saints of 1583 in the church of S.M.

Della Carib, Bologna, and during the next 12 years he painted a series of grand

altarpieces in which he revealed himself as an artist of commanding stature.

But the great turning point in Annibale's life came in 1595, when he was 35. In

that year he went to Rome to carry out decorations for Cardinal Odoardo Farnese

in his family palace, and this great commission gave Annibale his first real

opportunity to display his full powers. He lived in Rome for the rest of his

life and was never to see Bologna again.

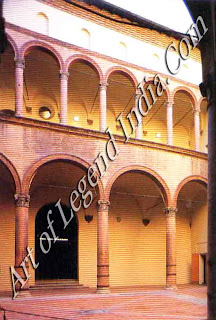

THE FARNESE PALACE

Odoardo

Farnese, who was made a cardinal in 1591, when he was 18, came from one of the

most important families of patrons and collectors in the history of Italian

art. The Farnese Palace was one of the most imposing buildings' in Rome (Michelangelo

was among the architects who had a hand in its design), and Odoardo wanted the

decoration of his apartments to match the grandeur of the exterior. In

particular he wanted a suitable setting for the superb collection of classical

statues (now in the Archaeological Museum in Naples) that he had inherited from

his great-uncle, Cardinal Alessandro Farnese. Annibale was first required to

decorate a small room called the Camerino that Odoardo used as a study, mainly

with scenes from the legend of Hercules, and in 1597 he moved on to the

Gallery, the work from which his fame is inseparable.

The

subject-matter of the decorative scheme seems a surprising choice for a

clergyman, as it represents the loves of the gods, or as Bellon described it

'human love governed by celestial love'. Cardinal Farnese's former tutor, the

eminent antiquarian Fulvio Orsini, was probably responsible for the elaborate

and learned 'programme.'

The

subject-matter of the decorative scheme seems a surprising choice for a

clergyman, as it represents the loves of the gods, or as Bellon described it

'human love governed by celestial love'. Cardinal Farnese's former tutor, the

eminent antiquarian Fulvio Orsini, was probably responsible for the elaborate

and learned 'programme.'

The

vaulted ceiling of the Gallery was painted between 1597 and 1600. Annibale had

some help from Agostino, who joined him in Rome in 1597, but the conception and

the bulk of the execution was his own. However, in 1600 the brothers parted

company after a quarrel. They differed greatly in temperament whereas Annibale

lived for his work and cared nothing for his appearance, Agostino was inclined

to put on airs and graces and sought the company of courtiers, whom Annibale

tried his best to avoid. According to Bellori, the rift occurred when Annibale,

who was 'untidy from painting', one day saw his brother in the street 'walking

with several cavaliers', called him aside and said to him: 'Remember, Agostino,

that you are the son of a tailor.' Soon after, Agostino left Rome for Parma

where he died two years later. Ludovico, who had remained in Bologna, now ran

the Academy on his own.

After

the completion of the vaulted ceiling, increasing demands prompted Annibale to

expand his studio and he had considerable help with the frescoes on the walls

of the Gallery from his assistants including Domenichino, who arrived in Rome

in 1602. Annibale was devoted to his pupils as well as to his own work. 'He

taught them not so much with words', says Bellori, 'as with example and

demonstration, and he treated .5 them with so much kindness that he often

neglected his own works. Without saying a word § he would go from one to the

other, and taking the brush from their hands would show them the rule by

example.' He also 'went through the streets and the churches with his pupils to

observe bad as well as good paintings. He would say to them "Thus one

should paint, thus one must not." His outspokenness could get him into

trouble, for when the Cavaliere d'Arpino, at the time one of the most renowned

artists in Italy, heard that Annibale had abused one of his paintings he

challenged him to a duel. Annibale's witty response was to pick up his brush

and say 'I challenge you!'

The

powerful, heroic style of figure painting that Annibale brought to maturity in

the Farnese Gallery reveals his study of Michelangelo, Raphael and classical

sculpture, but his frescoes have an exuberance that is completely personal.

Annibale planned his work with unstinting labour, making hundreds of

preparatory drawings, and his skill in working out every detail to perfection

while still keeping an overall sense of buoyant freshness is truly astonishing.

The Gallery was immediately hailed as a great work, and for the next two

centuries it was ranked with the Sistine Ceiling and Raphael's frescoes in the

Vatican as one of the world's supreme masterpieces of painting.

The

powerful, heroic style of figure painting that Annibale brought to maturity in

the Farnese Gallery reveals his study of Michelangelo, Raphael and classical

sculpture, but his frescoes have an exuberance that is completely personal.

Annibale planned his work with unstinting labour, making hundreds of

preparatory drawings, and his skill in working out every detail to perfection

while still keeping an overall sense of buoyant freshness is truly astonishing.

The Gallery was immediately hailed as a great work, and for the next two

centuries it was ranked with the Sistine Ceiling and Raphael's frescoes in the

Vatican as one of the world's supreme masterpieces of painting.

Annibale

was poorly rewarded for his long and concentrated efforts. He was paid an

allowance as he worked, but it was traditional for the patron to give the

artist a lump sum at the end of the commission. According to Bellori, 'the evil

guidance of a favourite courtier, Don Juan de Castro, a Spaniard, convinced the

Cardinal to reward him with only 500 gold scudi' which were 'brought in a

saucer to Annibale in his room'. Annibale was disdainful of wealth and

possessions 'he despised ostentation in people as well as in painting' said

Bellori 'but he was "struck dumb" at the ingratitude of one he had

served so well'. Bellori tells many stories of Annibale's kind nature and good

fellowship, which makes Cardinal Farnese's stinginess all the more deplorable.

Annibale

completed many other important works in Rome. He was in great demand as a

painter of altarpieces (in 1601 he worked on the same commission as Caravaggio

for paintings for the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo), but the most

remarkable and original of his later works are his landscapes. In about 1604 he

and his pupils painted a series of landscapes with sacred subjects for the

chapel of the Palazzo Aldobrandini, one of the paintings The Flight into Egypt

being entirely from Annibale's own hand: With these pictures he created the

type known as the ideal landscape grand, formal, stately and suitable as a

setting for serious mythological or religious subjects.

Annibale

completed many other important works in Rome. He was in great demand as a

painter of altarpieces (in 1601 he worked on the same commission as Caravaggio

for paintings for the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo), but the most

remarkable and original of his later works are his landscapes. In about 1604 he

and his pupils painted a series of landscapes with sacred subjects for the

chapel of the Palazzo Aldobrandini, one of the paintings The Flight into Egypt

being entirely from Annibale's own hand: With these pictures he created the

type known as the ideal landscape grand, formal, stately and suitable as a

setting for serious mythological or religious subjects.

OVERWHELMING MELANCHOLY

Despite

his success, the sorry conclusion to his labours in the Farnese Gallery sent

Annibale into a deep depression. Bellori says 'He was struck by apoplexy, which

impaired his speech and disturbed his intellect for some time.' He seems to

have had intervals of improvement, but during the last five years he hardly

painted at all, most of the work that issued from his studio being done by

assistants from his drawings. Bellori recounts that 'he went to Naples, where

he endeavoured to amuse himself and lighten his mind', but soon decided to

return to Rome and 'started back during the hot season, which generally is

dangerous'.

Despite

his success, the sorry conclusion to his labours in the Farnese Gallery sent

Annibale into a deep depression. Bellori says 'He was struck by apoplexy, which

impaired his speech and disturbed his intellect for some time.' He seems to

have had intervals of improvement, but during the last five years he hardly

painted at all, most of the work that issued from his studio being done by

assistants from his drawings. Bellori recounts that 'he went to Naples, where

he endeavoured to amuse himself and lighten his mind', but soon decided to

return to Rome and 'started back during the hot season, which generally is

dangerous'.

On 15

July 1609, soon after his return to Rome, Annibale died from a fever which was

worsened, according to Bellori, by 'amorous maladies'. He was 49. In accordance

with his last wishes Annibale was buried in the Pantheon, the last resting

place of Raphael, his greatest artistic hero. Bellori records the grief that

accompanied his funeral, 'almost as if it was Raphael again lying on the bier',

and expressed the hope that their two 'great souls are joined to God in

Heaven'.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Annibale

was the outstanding artist of the Carracci family. He combined intellect with a

great sense of fun but in later life suffered debilitating periods of illness

and depression.

Annibale

was the outstanding artist of the Carracci family. He combined intellect with a

great sense of fun but in later life suffered debilitating periods of illness

and depression.  Annibale

probably became an assistant (or perhaps a junior partner) in Ludovico's

workshop around 1580, and all three Carracci were working together by 1584,

when they collaborated on a series of mythological frescoes in the Palazzo Fava

in Bologna. At this stage of their career it was - and still is difficult to

distinguish between their hands, and Malvasia writes that when they were asked

to explain who was responsible for the different parts of another joint venture

a fresco cycle in the Palazzo Magnani in Bologna they replied: 'It is by the

Carracci - we have all made it.'

Annibale

probably became an assistant (or perhaps a junior partner) in Ludovico's

workshop around 1580, and all three Carracci were working together by 1584,

when they collaborated on a series of mythological frescoes in the Palazzo Fava

in Bologna. At this stage of their career it was - and still is difficult to

distinguish between their hands, and Malvasia writes that when they were asked

to explain who was responsible for the different parts of another joint venture

a fresco cycle in the Palazzo Magnani in Bologna they replied: 'It is by the

Carracci - we have all made it.'  Annibale's

first dated painting is a Crucifixion with Saints of 1583 in the church of S.M.

Della Carib, Bologna, and during the next 12 years he painted a series of grand

altarpieces in which he revealed himself as an artist of commanding stature.

But the great turning point in Annibale's life came in 1595, when he was 35. In

that year he went to Rome to carry out decorations for Cardinal Odoardo Farnese

in his family palace, and this great commission gave Annibale his first real

opportunity to display his full powers. He lived in Rome for the rest of his

life and was never to see Bologna again.

Annibale's

first dated painting is a Crucifixion with Saints of 1583 in the church of S.M.

Della Carib, Bologna, and during the next 12 years he painted a series of grand

altarpieces in which he revealed himself as an artist of commanding stature.

But the great turning point in Annibale's life came in 1595, when he was 35. In

that year he went to Rome to carry out decorations for Cardinal Odoardo Farnese

in his family palace, and this great commission gave Annibale his first real

opportunity to display his full powers. He lived in Rome for the rest of his

life and was never to see Bologna again.  The

subject-matter of the decorative scheme seems a surprising choice for a

clergyman, as it represents the loves of the gods, or as Bellon described it

'human love governed by celestial love'. Cardinal Farnese's former tutor, the

eminent antiquarian Fulvio Orsini, was probably responsible for the elaborate

and learned 'programme.'

The

subject-matter of the decorative scheme seems a surprising choice for a

clergyman, as it represents the loves of the gods, or as Bellon described it

'human love governed by celestial love'. Cardinal Farnese's former tutor, the

eminent antiquarian Fulvio Orsini, was probably responsible for the elaborate

and learned 'programme.'  The

powerful, heroic style of figure painting that Annibale brought to maturity in

the Farnese Gallery reveals his study of Michelangelo, Raphael and classical

sculpture, but his frescoes have an exuberance that is completely personal.

Annibale planned his work with unstinting labour, making hundreds of

preparatory drawings, and his skill in working out every detail to perfection

while still keeping an overall sense of buoyant freshness is truly astonishing.

The Gallery was immediately hailed as a great work, and for the next two

centuries it was ranked with the Sistine Ceiling and Raphael's frescoes in the

Vatican as one of the world's supreme masterpieces of painting.

The

powerful, heroic style of figure painting that Annibale brought to maturity in

the Farnese Gallery reveals his study of Michelangelo, Raphael and classical

sculpture, but his frescoes have an exuberance that is completely personal.

Annibale planned his work with unstinting labour, making hundreds of

preparatory drawings, and his skill in working out every detail to perfection

while still keeping an overall sense of buoyant freshness is truly astonishing.

The Gallery was immediately hailed as a great work, and for the next two

centuries it was ranked with the Sistine Ceiling and Raphael's frescoes in the

Vatican as one of the world's supreme masterpieces of painting.  Annibale

completed many other important works in Rome. He was in great demand as a

painter of altarpieces (in 1601 he worked on the same commission as Caravaggio

for paintings for the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo), but the most

remarkable and original of his later works are his landscapes. In about 1604 he

and his pupils painted a series of landscapes with sacred subjects for the

chapel of the Palazzo Aldobrandini, one of the paintings The Flight into Egypt

being entirely from Annibale's own hand: With these pictures he created the

type known as the ideal landscape grand, formal, stately and suitable as a

setting for serious mythological or religious subjects.

Annibale

completed many other important works in Rome. He was in great demand as a

painter of altarpieces (in 1601 he worked on the same commission as Caravaggio

for paintings for the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo), but the most

remarkable and original of his later works are his landscapes. In about 1604 he

and his pupils painted a series of landscapes with sacred subjects for the

chapel of the Palazzo Aldobrandini, one of the paintings The Flight into Egypt

being entirely from Annibale's own hand: With these pictures he created the

type known as the ideal landscape grand, formal, stately and suitable as a

setting for serious mythological or religious subjects.  Despite

his success, the sorry conclusion to his labours in the Farnese Gallery sent

Annibale into a deep depression. Bellori says 'He was struck by apoplexy, which

impaired his speech and disturbed his intellect for some time.' He seems to

have had intervals of improvement, but during the last five years he hardly

painted at all, most of the work that issued from his studio being done by

assistants from his drawings. Bellori recounts that 'he went to Naples, where

he endeavoured to amuse himself and lighten his mind', but soon decided to

return to Rome and 'started back during the hot season, which generally is

dangerous'.

Despite

his success, the sorry conclusion to his labours in the Farnese Gallery sent

Annibale into a deep depression. Bellori says 'He was struck by apoplexy, which

impaired his speech and disturbed his intellect for some time.' He seems to

have had intervals of improvement, but during the last five years he hardly

painted at all, most of the work that issued from his studio being done by

assistants from his drawings. Bellori recounts that 'he went to Naples, where

he endeavoured to amuse himself and lighten his mind', but soon decided to

return to Rome and 'started back during the hot season, which generally is

dangerous'.

0 Response to "Italian Great Artist Annibale Carracci Life"

Post a Comment