The City of Nuremberg

Nuremberg

was a microcosm of 15th-century cultural life. The arts, learning and printing

flourished there, fostered by the city's enlightened climate and commercial

prosperity.

Durer's

Nuremberg was one of the liveliest, most exciting cities in 15th-century

Europe. Referred to variously by contemporaries as the 'Florence of the North'

and as a 'German Athens', it was a major cultural, commercial and artistic

centre at the hub of the Holy Roman Empire. The successes of its citizens in

all spheres of life were impressive, and were crowned by the achievements of Durer

himself, whose fame was to stretch far beyond the city boundaries.

Germany

in the 15th century was composed of various principalities, dukedoms,

bishoprics and cities which were loosely grouped under the authority of the

Holy Roman Empire of the German nation. By Durer's time, the cities were

probably the most powerful section of the Empire, enjoying considerable

prosperity and stable government. This was especially true of the 65 or so

Imperial cities, which were then largely independent, except for a number of

stipulated obligations to the emperor such as tax payments, hospitality and

allegiance. In return, the emperor guaranteed the citizens peace, and granted

them certain specific privileges.

Germany

in the 15th century was composed of various principalities, dukedoms,

bishoprics and cities which were loosely grouped under the authority of the

Holy Roman Empire of the German nation. By Durer's time, the cities were

probably the most powerful section of the Empire, enjoying considerable

prosperity and stable government. This was especially true of the 65 or so

Imperial cities, which were then largely independent, except for a number of

stipulated obligations to the emperor such as tax payments, hospitality and

allegiance. In return, the emperor guaranteed the citizens peace, and granted

them certain specific privileges.

Imperial

cities such as Ulm, Strasbourg, Augsburg and Cologne were major European

centres during this period but one of the most important of all was Nuremberg.

The esteem in which this city was held was reflected in the fact that as well

as being a venue of Imperial Diets or parliaments it was the city in which the

Imperial regalia and relics were housed from 1423.

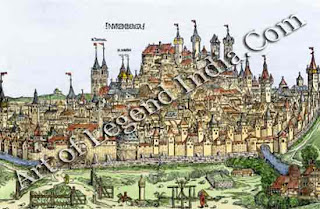

Visually,

Nuremberg must have been an extremely attractive city. Built on the river

Pegnitz, it was surrounded by woods and the view of the walled city was

dominated by the grand imperial castle, set on a hill overlooking the

red-roofed houses. The triple encircling walls had four gates and 128 towers.

Other landmarks were the impressive churches of St Lorenz and St Sebald.

Living

conditions in Nuremberg, however, must have been fairly cramped. At the time of

Durer's birth the population was about 40,000. Within the city walls, which

were only about 8,000 paces in circumference, there were over five hundred streets,

and thousands of public and private buildings.

The

city's government was in the hands of its Council which was' made up of 42 men,

drawn largely from the urban patriciate. The Council ruled absolutely and very

successfully, showing continual concern for the well-being of the citizens.

Almost uniquely among Imperial cities, Nuremberg was renowned for its stability

and freedom from internal trouble or strife of any sort, and this was mostly

because the Council simply did not allow it to happen.

A CENTRE OF COMMERCE

International

comings and goings were an accepted way of life in Nuremberg and resulted from

the city's success as the major business centre of south Germany. All types of

trades and crafts were represented in the city furriers, belt-makers,

cloth-makers, armourers and paper-makers. The silver and goldsmiths were

particularly prominent and many of Germany's finest artists began their careers

in these crafts. Durer himself was apprenticed as a goldsmith, and both his

father and grandfather were masters of the craft.

The

prosperity generated by Nuremberg's commercial successes meant that the

standard of living was generally very high for almost all of its citizens, and

they lived comfortably according to their own social standing. This is proved

by the fact that nearly every family had their own house, which also served as

a workplace. The people dressed well, and ate well indeed, it was normal for a

citizen of Nuremberg to have at least one meat dish a day. The most popular

drink was beer which was brewed locally.

The

prosperity generated by Nuremberg's commercial successes meant that the

standard of living was generally very high for almost all of its citizens, and

they lived comfortably according to their own social standing. This is proved

by the fact that nearly every family had their own house, which also served as

a workplace. The people dressed well, and ate well indeed, it was normal for a

citizen of Nuremberg to have at least one meat dish a day. The most popular

drink was beer which was brewed locally.

However,

the well-ordered city of Nuremberg was not only renowned for its commercial and

material successes. Throughout Durer's lifetime it was also famous as a centre

of learning, despite the fact that it had no university. Largely due to its

trade links with Italy, Nuremberg had been very much influenced by the southern

Renaissance and had become one of the major centres of humanism in Germany.

Scholars were drawn to Nuremberg from all over Europe, and the city also had its

own humanist 'society', of which a prominent member was Willibald Pirckheimer,

a close friend of Duren The mathematician, Johann Muller who further developed

trigonometry settled in Nuremberg in 1471, because here, as he said he could

easily 'keep in touch with the learned of all countries. .

FLOWERING OF THE ARTS

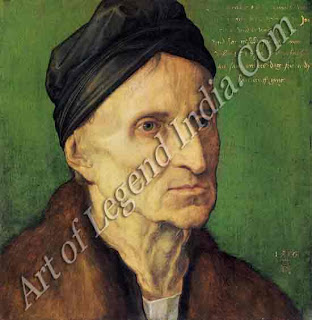

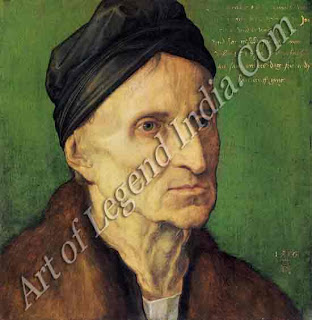

The

presence of humanism in the city, combined with its affluence, provided a

flourishing climate for art in the late 15th century. The prosperity of the

citizens encouraged them to patronize the local painters and sculptors, and the

city churches, in particular, were filled with artistic decorations donated by

parishioners. In fact the city's artistic life was at its peak between 1490 and

1525, the very period in which Durer came to prominence. One of the most famous

of these artists was Michael Wolgemut, now remembered chiefly as Durer's

teacher. During the last third of the 15th century he was Nuremberg's principal

painter, printmaker and stained-glass designer. He became an independent master

in 1473, and set up one of the largest workshops in the city.

The

thriving artistic profession in 15th-century Nuremberg was very closely

connected to the city's commercial skills. The two areas complemented each

other, and many men were active in both fields. These links between trade and culture

were nowhere more evident than in one of the city's most modem and most

successful business ventures - the establishment of printing. Nuremberg was

famous among the Imperial cities for its printmaking and this reputation was

earned largely by the work of one man, Anton Koberger, Durer's godfather. In 1470,

only a decade after printing first appeared in the city, Koberger set up his

own press and combined printing, publishing and bookselling in his business. He

was, by any standards, phenomenally successful.

The

thriving artistic profession in 15th-century Nuremberg was very closely

connected to the city's commercial skills. The two areas complemented each

other, and many men were active in both fields. These links between trade and culture

were nowhere more evident than in one of the city's most modem and most

successful business ventures - the establishment of printing. Nuremberg was

famous among the Imperial cities for its printmaking and this reputation was

earned largely by the work of one man, Anton Koberger, Durer's godfather. In 1470,

only a decade after printing first appeared in the city, Koberger set up his

own press and combined printing, publishing and bookselling in his business. He

was, by any standards, phenomenally successful.

Koberger's

success coincided with dramatic improvements in paper manufacture which

resulted in an explosion of printed material between the years 1473 and 1513;

Koberger's press produced more than 200 titles. At its height, his workshop had

more than 24 presses, with over one hundred compositors, proof-readers,

illuminators and binders. He set up European wide trade links, and even had his

own agency in Paris. Koberger was the first publisher to climb the social scale

as a result of his commercial success, and even became a member of the city's

most elite group, the Council. The links between trade and art in Nuremberg are

highlighted by the fact that Koberger allowed his godson, Albrecht Durer, to

use his presses and types for the Apocalypse series.

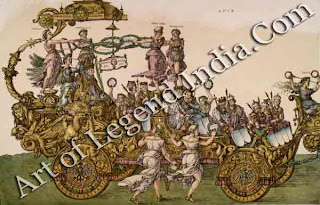

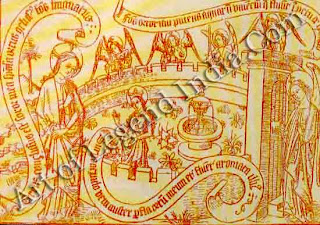

One of

Koberger's publications perfectly demonstrates Nuremberg's dominance in all

spheres of German life during the Renaissance. This was the production, in

1493, of the Nuremberg Chronicle; the first great illustrated book, which told

the world's history from the Creation to 1493.

The

Chronicle was written by a prominent local humanist, Hartmann Schedel, who

collaborated with the printer Koberger and the artist Wolgemut to produce what

is probably the most famous 15th-century publication after Gutenberg's Bible.

Published in both Latin and German, the Nuremberg Chronicle is famous today for

its woodcut illustrations. These were done in Wolgemut's workshop, and some

were probably the work of his apprentice, Durer. The Nuremberg Chronicle the

fruit of the city's intellectual, commercial and artistic endeavours leaves us

with a fitting and lasting testimony to the pre-eminence of the Imperial city

of Nuremberg in Durer's lifetime.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Germany

in the 15th century was composed of various principalities, dukedoms,

bishoprics and cities which were loosely grouped under the authority of the

Holy Roman Empire of the German nation. By Durer's time, the cities were

probably the most powerful section of the Empire, enjoying considerable

prosperity and stable government. This was especially true of the 65 or so

Imperial cities, which were then largely independent, except for a number of

stipulated obligations to the emperor such as tax payments, hospitality and

allegiance. In return, the emperor guaranteed the citizens peace, and granted

them certain specific privileges.

Germany

in the 15th century was composed of various principalities, dukedoms,

bishoprics and cities which were loosely grouped under the authority of the

Holy Roman Empire of the German nation. By Durer's time, the cities were

probably the most powerful section of the Empire, enjoying considerable

prosperity and stable government. This was especially true of the 65 or so

Imperial cities, which were then largely independent, except for a number of

stipulated obligations to the emperor such as tax payments, hospitality and

allegiance. In return, the emperor guaranteed the citizens peace, and granted

them certain specific privileges.  The

prosperity generated by Nuremberg's commercial successes meant that the

standard of living was generally very high for almost all of its citizens, and

they lived comfortably according to their own social standing. This is proved

by the fact that nearly every family had their own house, which also served as

a workplace. The people dressed well, and ate well indeed, it was normal for a

citizen of Nuremberg to have at least one meat dish a day. The most popular

drink was beer which was brewed locally.

The

prosperity generated by Nuremberg's commercial successes meant that the

standard of living was generally very high for almost all of its citizens, and

they lived comfortably according to their own social standing. This is proved

by the fact that nearly every family had their own house, which also served as

a workplace. The people dressed well, and ate well indeed, it was normal for a

citizen of Nuremberg to have at least one meat dish a day. The most popular

drink was beer which was brewed locally.  The

thriving artistic profession in 15th-century Nuremberg was very closely

connected to the city's commercial skills. The two areas complemented each

other, and many men were active in both fields. These links between trade and culture

were nowhere more evident than in one of the city's most modem and most

successful business ventures - the establishment of printing. Nuremberg was

famous among the Imperial cities for its printmaking and this reputation was

earned largely by the work of one man, Anton Koberger, Durer's godfather. In 1470,

only a decade after printing first appeared in the city, Koberger set up his

own press and combined printing, publishing and bookselling in his business. He

was, by any standards, phenomenally successful.

The

thriving artistic profession in 15th-century Nuremberg was very closely

connected to the city's commercial skills. The two areas complemented each

other, and many men were active in both fields. These links between trade and culture

were nowhere more evident than in one of the city's most modem and most

successful business ventures - the establishment of printing. Nuremberg was

famous among the Imperial cities for its printmaking and this reputation was

earned largely by the work of one man, Anton Koberger, Durer's godfather. In 1470,

only a decade after printing first appeared in the city, Koberger set up his

own press and combined printing, publishing and bookselling in his business. He

was, by any standards, phenomenally successful.

0 Response to "German Great Artist Albrecht Durer - The City of Nuremberg"

Post a Comment