A Perfect Likeness

Holbein's ability to achieve almost photographic realism in

his painting made his reputation as a portrait painter, and has given posterity

an invaluable record of the members of the Tudor court.

Holbein's reputation is based on the brilliantly observed

portraits which he painted in England during the reign of Henry VIII. Their

realism is astonishing even today, and it is easy to understand the reaction of

Holbein's friend, the great scholar Erasmus, when he received the artist's

drawing of Sir Thomas More and his family: 'It is so completely successful,

that I should scarcely be able to see you better if I were with you'.

Yet Holbein did not start his career as a portrait painter.

He trained in his father's workshop in Augsburg and that of Hans Herbster in

Basel, where he not only learnt the techniques of oil painting, but also those

of book illustration and the decorative arts. Holbein's early paintings were

mainly monumental and religious works, stylistically in the Northern tradition

of Darer and Grunewald. By the late 1520s, a new influence can be seen. In The

Meyer Madonna (1526), the Northern emphasis on sharply observed realism and

incisive line is evident, but the classical motifs, calm symmetry and use of

sfumato to soften the Madonna's features show a debt to Italian Renaissance art

particularly that of Leonardo.

Many of Holbein's early religious works were probably lost

during the violent iconoclasm (destruction of holy images) of the Reformation.

This movement also put paid to a major source of potential income church

commissions which is why Holbein was forced to leave Basel in search of work in

England.

MORE AND HIS CIRCLE

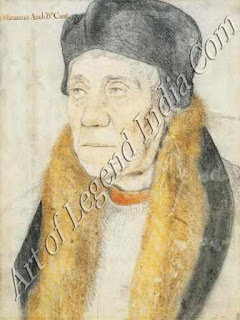

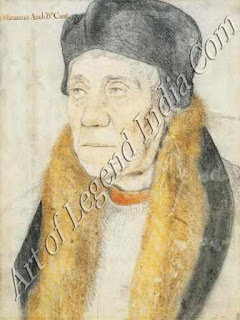

Holbein already had quite a reputation for portraiture in England,

since his portrait of Erasmus had been presented to Archbishop Warham. And most

of his first visit to England (1526-1528) was spent mainly in the production of

portraits of More and his circle most of whom knew Erasmus. These are among the

most astonishing likenesses in the history of art, and would certainly have

astounded their Tudor sitters who had never seen anything like them before. Sir

Thomas More is perfect in both its draughtsmanship and its apparent solidity in

Holbein's art, line defines form. More's face has been scrutinized and

reproduced with an almost photographic accuracy even down to the silver-tinged

stubble on his chin. And Holbein's vision is so penetrating that his realism is

not only skin deep: the slightly tensed brow above the tranquil eyes reveals

More's thoughtful character.

Holbein already had quite a reputation for portraiture in England,

since his portrait of Erasmus had been presented to Archbishop Warham. And most

of his first visit to England (1526-1528) was spent mainly in the production of

portraits of More and his circle most of whom knew Erasmus. These are among the

most astonishing likenesses in the history of art, and would certainly have

astounded their Tudor sitters who had never seen anything like them before. Sir

Thomas More is perfect in both its draughtsmanship and its apparent solidity in

Holbein's art, line defines form. More's face has been scrutinized and

reproduced with an almost photographic accuracy even down to the silver-tinged

stubble on his chin. And Holbein's vision is so penetrating that his realism is

not only skin deep: the slightly tensed brow above the tranquil eyes reveals

More's thoughtful character.

Holbein's painting depended upon his phenomenal drawing

ability. And it seems that, for him, drawing could be an end in itself, not

merely a preliminary to painting. At first, his drawings were executed in

chalks, which were sometimes heightened with water-colour. But after his return

to England in 1532, the delicacy of this technique was replaced by the more

vigorous and emphatic medium of ink. The collections of drawings at Windsor are

among Holbein's most popular works.

Part of Holbein's assured mastery of line was his ability to

capture a likeness very quickly. It is known, for example, that he was only

granted a sitting of three hours for his portrait of the Duchess of Milan. This

was enough for him to make a 'very perfect likeness'. During his first English

visit, he was not inundated by commissions, and could presumably take longer,

but once he entered royal service, such swiftness of execution would have been

necessary to supply increased demand.

A MECHANICAL AID

It has been suggested that Holbein may have made use of some

sort of mechanical aid to allow him to record the outline of the sitter's face

as fast as possible. Again, this would presumably only have been necessary

during his second visit to England. If he did use a mechanical aid, it may have

been a kind of tracing apparatus, of the type other artists such as Darer and

Leonardo are known to have used. This consisted of a peep-hole and a pane of

glass. The artist looked through the peep-hole and glass directly at the sitter

rather in the way that the sights of a rifle are used to ensure a perfect line

of vision and traced the outline of the sitters' features on to the glass with

an oil crayon. The outlines would then be transferred on to paper.

It has been suggested that Holbein may have made use of some

sort of mechanical aid to allow him to record the outline of the sitter's face

as fast as possible. Again, this would presumably only have been necessary

during his second visit to England. If he did use a mechanical aid, it may have

been a kind of tracing apparatus, of the type other artists such as Darer and

Leonardo are known to have used. This consisted of a peep-hole and a pane of

glass. The artist looked through the peep-hole and glass directly at the sitter

rather in the way that the sights of a rifle are used to ensure a perfect line

of vision and traced the outline of the sitters' features on to the glass with

an oil crayon. The outlines would then be transferred on to paper.

The paintings themselves were executed on wooden panels, to

which Holbein would transfer his drawings using a grey wash. He then worked up

the painted surface with meticulous accuracy, often using notes on colour and

jewellery details to help him attain a perfect reproduction of what he had

originally observed.

In the first years of Holbein's second visit to England,

when he was still hoping to attract royal favour, he often made a point of

showing off his ability to record stunning likenesses not only of faces, but

also of surface textures. In his portrait of the German merchant George Gisze

the lush folds of pink velvet are set against the woven intricacies of the

Turkish rug with an almost tangible realism. And as if to hammer home the point,

Holbein has placed a bunch of carnations in a thin glass vase which is painted

with exquisite accuracy, and through which is seen the stems of the flowers and

the woven threads of the rug.

A CHANGE IN STYLE

George Gisze is also characteristic of this particular phase

in Holbein's art in the abundance of props which surround the sitter as

attributes of his profession. About three years after this particularly

'flashy' painting, Holbein's portraits altered in a most dramatic way. The

compositions themselves became simpler, with the sitters placed against plain

backgrounds of blue or green. The lack of depth in these backdrops is often

accentuated by Latin inscriptions, placed on either side of the sitter's head,

usually indicating the date and his or her age.

The plain backgrounds serve to heighten the impact of the

portraits themselves. The flatness of composition became particularly

pronounced in many of the half-length portraits which Holbein executed of and

for Henry VIII, where it was accompanied by an increased emphasis on linear

patterning. In his portrait of Henry VIII, for example, the predominance of

line is still evident, but it is put to a more decorative purpose. The

sumptuous patterns of Henry's doublet and jewels, the flattened arms, and the

head and hat almost cut out against the blue background all combine to create

an icon-like image appropriate for a monarch who was also the Supreme Head of

the Church of England. Although the face is as individualized as that of Sir

Thomas More painted nine years previously, the effect of the painting is

entirely different. Sir Thomas More is a portrait of a man, Henry VIII is an

image of god-like majesty.

It was Holbein's ability to create such spectacles of power

that won him the chance to paint his most prestigious work, the Whitehall

fresco. For the king did not want a family portrait, he wanted an image of

absolute authority that combined physical might with symbolic legitimacy.

It was Holbein's ability to create such spectacles of power

that won him the chance to paint his most prestigious work, the Whitehall

fresco. For the king did not want a family portrait, he wanted an image of

absolute authority that combined physical might with symbolic legitimacy.

It is an irony that Holbein's consummate achievement has not

existed for nearly 300 years it was destroyed in a fire in 1698. But the

surviving copies and cartoon leave no doubt that the bloated, bulging, pig-eyed

figure of Henry VIII must have been awe-inspiring. Visitors to the palace were

said to be 'abashed' and 'annihilated' and many believed they were in the

presence of the king himself.

In his cartoon for Henry's portrait, Holbein shows him

turning slightly towards the queen, Jane Seymour; in the final painting,

however, the king confronts the spectator directly. Obviously, Holbein's

rendering of him was not designed to flatter, it was designed to glorify and

magnify. The impression of raw power and indomitable energy is created partly

by the sheer bulk of the figure, and partly by the contrast of Henry's

challenging, virile pose with the more spiritual calm of the other three

figures, whose eyes do not engage the spectator's.

ART AND PROPAGANDA

Holbein achieved these effects by using a whole range of

artistic devices, but most of all he drew on the recognizable vocabulary of

religious painting. '['he way in which the group is posed, for example, is

reminiscent of the standard Renaissance arrangement for a Madonna and child

flanked by saints. Holbein translated the language of religion into that of

politics, and for the Holy Family he substituted the royal family. In this way

he was able to create an image which simultaneously demonstrated the political

supremacy of the Tudor dynasty, and the supremacy of Henry himself as head of

the Church in England. In the process, Holbein had combined art and propaganda.

Writer – Marshall

Cavendish

Holbein already had quite a reputation for portraiture in England,

since his portrait of Erasmus had been presented to Archbishop Warham. And most

of his first visit to England (1526-1528) was spent mainly in the production of

portraits of More and his circle most of whom knew Erasmus. These are among the

most astonishing likenesses in the history of art, and would certainly have

astounded their Tudor sitters who had never seen anything like them before. Sir

Thomas More is perfect in both its draughtsmanship and its apparent solidity in

Holbein's art, line defines form. More's face has been scrutinized and

reproduced with an almost photographic accuracy even down to the silver-tinged

stubble on his chin. And Holbein's vision is so penetrating that his realism is

not only skin deep: the slightly tensed brow above the tranquil eyes reveals

More's thoughtful character.

Holbein already had quite a reputation for portraiture in England,

since his portrait of Erasmus had been presented to Archbishop Warham. And most

of his first visit to England (1526-1528) was spent mainly in the production of

portraits of More and his circle most of whom knew Erasmus. These are among the

most astonishing likenesses in the history of art, and would certainly have

astounded their Tudor sitters who had never seen anything like them before. Sir

Thomas More is perfect in both its draughtsmanship and its apparent solidity in

Holbein's art, line defines form. More's face has been scrutinized and

reproduced with an almost photographic accuracy even down to the silver-tinged

stubble on his chin. And Holbein's vision is so penetrating that his realism is

not only skin deep: the slightly tensed brow above the tranquil eyes reveals

More's thoughtful character.  It has been suggested that Holbein may have made use of some

sort of mechanical aid to allow him to record the outline of the sitter's face

as fast as possible. Again, this would presumably only have been necessary

during his second visit to England. If he did use a mechanical aid, it may have

been a kind of tracing apparatus, of the type other artists such as Darer and

Leonardo are known to have used. This consisted of a peep-hole and a pane of

glass. The artist looked through the peep-hole and glass directly at the sitter

rather in the way that the sights of a rifle are used to ensure a perfect line

of vision and traced the outline of the sitters' features on to the glass with

an oil crayon. The outlines would then be transferred on to paper.

It has been suggested that Holbein may have made use of some

sort of mechanical aid to allow him to record the outline of the sitter's face

as fast as possible. Again, this would presumably only have been necessary

during his second visit to England. If he did use a mechanical aid, it may have

been a kind of tracing apparatus, of the type other artists such as Darer and

Leonardo are known to have used. This consisted of a peep-hole and a pane of

glass. The artist looked through the peep-hole and glass directly at the sitter

rather in the way that the sights of a rifle are used to ensure a perfect line

of vision and traced the outline of the sitters' features on to the glass with

an oil crayon. The outlines would then be transferred on to paper.  It was Holbein's ability to create such spectacles of power

that won him the chance to paint his most prestigious work, the Whitehall

fresco. For the king did not want a family portrait, he wanted an image of

absolute authority that combined physical might with symbolic legitimacy.

It was Holbein's ability to create such spectacles of power

that won him the chance to paint his most prestigious work, the Whitehall

fresco. For the king did not want a family portrait, he wanted an image of

absolute authority that combined physical might with symbolic legitimacy.

0 Response to "German Great Artist Hans Holbein - A Perfect Likeness "

Post a Comment