The

Dravidian beliefs were deeply enough entrenched in India to survive the changes

brought about by the successive waves of Aryan invasion that took place from

about i800 B.C. and led to or at least coincided with the decline and

disappearance of the Indus Valley cities. In a number of particulars the

iconography of the Indus Valley civilisation, and therefore possibly beliefs,

'reappears with the first Hindu cult images of gods of the firstto

fourth centuries A.D. Thus Shiva and his consort resemble the Dravidian cult

figures in many respects, Shiva often being depicted in a cross-legged yogic

posture with the bull Nandi as his symbol, and his consort being associated

with human sacrifice. Other Hindu deities too are characteristically

accompanied by particular animals, often a 'vehicle'. And the graceful yakshi

figures that feature so prominently in early Buddhist sculpture of the third to

first centuries B.C., when no images of the Buddha himself were made, appear to

be derived from Dravidian female nature deities associated with trees and water

and symbolising the fertility of water and earth. As in the Indus civilization

seals, they are accompanied by naturalistic animals, and some-times by a male

ministrant or counterpart, the yaksha. Such figures later influenced the

depiction of the Buddha in the sculptures made at Mathura and installed at

Sarnath.

The

Dravidian beliefs were deeply enough entrenched in India to survive the changes

brought about by the successive waves of Aryan invasion that took place from

about i800 B.C. and led to or at least coincided with the decline and

disappearance of the Indus Valley cities. In a number of particulars the

iconography of the Indus Valley civilisation, and therefore possibly beliefs,

'reappears with the first Hindu cult images of gods of the firstto

fourth centuries A.D. Thus Shiva and his consort resemble the Dravidian cult

figures in many respects, Shiva often being depicted in a cross-legged yogic

posture with the bull Nandi as his symbol, and his consort being associated

with human sacrifice. Other Hindu deities too are characteristically

accompanied by particular animals, often a 'vehicle'. And the graceful yakshi

figures that feature so prominently in early Buddhist sculpture of the third to

first centuries B.C., when no images of the Buddha himself were made, appear to

be derived from Dravidian female nature deities associated with trees and water

and symbolising the fertility of water and earth. As in the Indus civilization

seals, they are accompanied by naturalistic animals, and some-times by a male

ministrant or counterpart, the yaksha. Such figures later influenced the

depiction of the Buddha in the sculptures made at Mathura and installed at

Sarnath.

The

Dravidian peoples, who spread into almost every part of India and Sri Lanka,

were a mixture of native populations of India and Proto-Drav-Indians, who seem

to have entered India in waves from about 4000 to 2500 B.C. They introduced a

neolithic village culture based on agriculture or hunting in Baluchistan and

Sind, and this enriched and incorporated elements of the mesolithic culture

evidenced about 5000 B.C. by the earliest known paintings in rock shelters of

bison, elephant and buffalo, as far afield as Adamgarh in central India and

Badami in the southern Deccan. The so-called Indus Valley civilisation which

developed from this stretched from Afghanistan to beyond present Delhi and from

the Makeran coast of Baluchistan far down into Gujerat. Great cities such as

Mohenjodaro and Harappa (in present-day Pakistan) and Kalibangan in India rose

during the third millennium B.C. and reached the height of their considerable

material culture about 2150-1750 B.C. (as Carbon-14 dating has shown, somewhat

later than thought when the sites were first excavated in the 19zos).

From

the archaeological excavations it is clear that the great cities had risen

above a purely agricultural economy and conducted trade over-land and by sea

with places as far afield as Mesopotamia. The Sumerian-style seals found at

each of the major sites give us the best clues to what their deities and myths

may have been, though the accompanying inscriptions have not so far been

satisfactorily deciphered. Nor can we know whether the remarkable visual

similarities indicate beliefs derived from Mesopotamia or merely an iconography

borrowed from there.

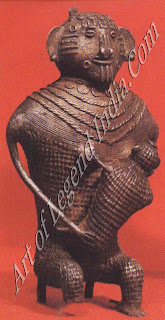

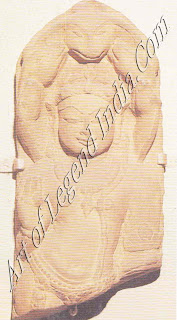

Whatever

the case, the Dravidians, as an agricultural people, clearly worshipped deities

connected in one way or another with fertility. There were two main elements in

this, both analogous to Mesopotamian cults: phallic worship typified in the

seals found at Harappa, which show a god seated with legs crossed and wearing

bull's horns (the bull being a universal symbol of male potency); and the cult

of mother goddesses, most plainly depicted on seals which show plants growing

from the womb of a female deity, or which show a naked goddess before whom a

human sacrifice is being performed. Such figures are accompanied by animal

ministrants, the goddess by what appears to be half-bull, half-ram, and the god

by deer, birds, an elephant, a tiger, a rhinoceros and a buffalo or in other

cases by votive serpents. Serpent worship certainly antedates the Aryan

invasions, though it was incorporated into both Buddhist and Hindu iconography.

Significantly, from Aryan times onwards the majority of serpents or Nagas were

considered demons, but a few were highly honoured as divine. This age old

reverence for animals, alien to Aryan belief, may well have contributed to

Buddhist and Hindu ideas of reincarnation.

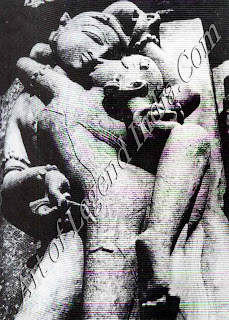

The

Dravidian beliefs were deeply enough entrenched in India to survive the changes

brought about by the successive waves of Aryan invasion that took place from

about i800 B.C. and led to or at least coincided with the decline and

disappearance of the Indus Valley cities. In a number of particulars the

iconography of the Indus Valley civilisation, and therefore possibly beliefs,

'reappears with the first Hindu cult images of gods of the firstto

fourth centuries A.D. Thus Shiva and his consort resemble the Dravidian cult

figures in many respects, Shiva often being depicted in a cross-legged yogic

posture with the bull Nandi as his symbol, and his consort being associated

with human sacrifice. Other Hindu deities too are characteristically

accompanied by particular animals, often a 'vehicle'. And the graceful yakshi

figures that feature so prominently in early Buddhist sculpture of the third to

first centuries B.C., when no images of the Buddha himself were made, appear to

be derived from Dravidian female nature deities associated with trees and water

and symbolising the fertility of water and earth. As in the Indus civilization

seals, they are accompanied by naturalistic animals, and some-times by a male

ministrant or counterpart, the yaksha. Such figures later influenced the

depiction of the Buddha in the sculptures made at Mathura and installed at

Sarnath.

The

Dravidian beliefs were deeply enough entrenched in India to survive the changes

brought about by the successive waves of Aryan invasion that took place from

about i800 B.C. and led to or at least coincided with the decline and

disappearance of the Indus Valley cities. In a number of particulars the

iconography of the Indus Valley civilisation, and therefore possibly beliefs,

'reappears with the first Hindu cult images of gods of the firstto

fourth centuries A.D. Thus Shiva and his consort resemble the Dravidian cult

figures in many respects, Shiva often being depicted in a cross-legged yogic

posture with the bull Nandi as his symbol, and his consort being associated

with human sacrifice. Other Hindu deities too are characteristically

accompanied by particular animals, often a 'vehicle'. And the graceful yakshi

figures that feature so prominently in early Buddhist sculpture of the third to

first centuries B.C., when no images of the Buddha himself were made, appear to

be derived from Dravidian female nature deities associated with trees and water

and symbolising the fertility of water and earth. As in the Indus civilization

seals, they are accompanied by naturalistic animals, and some-times by a male

ministrant or counterpart, the yaksha. Such figures later influenced the

depiction of the Buddha in the sculptures made at Mathura and installed at

Sarnath.

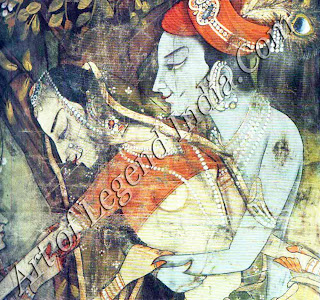

The yakshi

and yaksha figures survived into Hinduism too, in trans-muted though still

powerful form, as guardians of wealth, and they are thought to have influenced

the development in India of cosmic sexual symbolism. From being

personifications of the ever-renewing sap of life, whose embrace has the power

to fertilise trees, yakshis developed into the three great female deities of

Indian rivers, Ganga, Yamuna and Sarasvati, source of eternal sustenance, and

so into the culminating personification of abundance, the goddess Lakshmi. In

Tantric belief, whose influence is so strongly reflected in the countless

images of Mithuna, embracing couples, that adorn Indian temples, the female

principle of voluptuous activity is the motive force that sustains the universe,

because without it the male principle of static, transcendental potentiality

would remain in inert passivity. They illustrate, to European eyes sometimes in

gross physical form, spiritual union with the divine. This Tantric trend, which

became powerful in the fifth century A.D. during the Golden Age of the Gupta

empire, is in striking contrast to the ascetic stream in Indian tradition, yet

both seem equally to derive from the pre-Aryan past, and stand in a dialectical

relationship to each other, opposite poles of the human approach to existence.

Writer-

Veronica Lons

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "Early Deities of Indian Mythology"

Post a Comment