The Shock of Reality

Courbet

insisted that it was the artist's job to paint only the world he knew. And his

uncompromising images of contemporary rural society rocked the complacent

attitudes of Parisian observers.

Courbet's

fame today rests on his reputation as the leader of the Realist movement. But

despite the fact that he called his 1855 one-man show the 'Pavilion of

Realism', it was not necessarily a label he relished. In the preface to his

exhibition catalogue, he declared that the title of 'realist had been thrust

upon him. And in the remainder of his manifesto, he endeavoured to remove the

misconceptions about his art and to put forward his own aims: 'to record the

manners, ideas and aspects of the age as I myself saw them, to be a man as well

as a painter to create a living art.'

POPULAR PRINTS

Yet the

methods that Courbet used to create his 'living art' were in some ways derived

from the art of the past. In many of his most famous canvases, he made

traditional use of secondary sources. For Burial at Ornans, for example, he

incorporated elements borrowed from popular prints of the day with portraits of

his family and neighbours; the model in The Studio was taken from a photograph,

and some of his landscapes were composites, built up from separate studies.

Yet the

methods that Courbet used to create his 'living art' were in some ways derived

from the art of the past. In many of his most famous canvases, he made

traditional use of secondary sources. For Burial at Ornans, for example, he

incorporated elements borrowed from popular prints of the day with portraits of

his family and neighbours; the model in The Studio was taken from a photograph,

and some of his landscapes were composites, built up from separate studies.

In his

work pattern, too, Courbet adhered to the conventional method: sketching during

the summer and working up exhibition pieces in the studio during the winter.

But in his insistence on painting only contemporary subjects, and in his presentation,

Courbet's art was revolutionary.

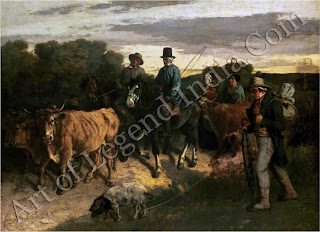

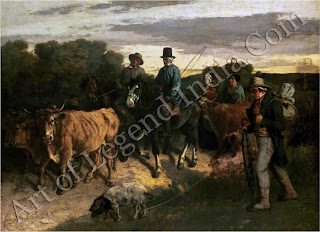

Even

the size of his canvases was the subject of much concern and comment. There was

an accepted convention in Salon painting that only lofty subject matter usually

historical, Biblical or mythological scenes was appropriate for large-scale

depiction. For peasant paintings such as Courbet's, a more moderate size was

expected. But Courbet rejected this convention. His huge paintings of peasants

baffled shocked and even threatened many city-dwelling observers, who searched

in vain for some symbolic content.

Courbet

was also criticized for his perverse liking for ugly subjects. But the

'ugliness' of his art worked on more than one level. While the fat, dimpled

nude in The Bathers was simply seen as physically repulsive, the discordant

composition and stiff, unattractive figures of The Peasants of Flagey were more

unsettling. In this uneasy composition, Courbet evoked in the most direct

manner, the uneasy social situation of the peasant-bourgeois characters in the

scene.

But in

his disrespect for 'beauty', Courbet was reacting against the strictures of

academic painting, where there was a tendency to idealize. In Courbees view, it

was not the business of the artist to depict historical or imaginary scenes, but

to paint only what he knew the contemporary world. As for the art of the Old

Masters, that was to be learnt from, not mimicked.

It was

partly for this reason that Courbet was so reticent about his own conventional

training and probably why he was so reluctant to take on students of his own.

When, for a very brief period in 1862, he was persuaded to run a studio, he was

determined that his pupils should not be tempted by their life-classes into

painting only nudes in heroic poses. Hence the spectacle which greeted one

visitor of a red and white bull, wild-eyed and flicking its tail, serving as

the artists' model.

It was

partly for this reason that Courbet was so reticent about his own conventional

training and probably why he was so reluctant to take on students of his own.

When, for a very brief period in 1862, he was persuaded to run a studio, he was

determined that his pupils should not be tempted by their life-classes into

painting only nudes in heroic poses. Hence the spectacle which greeted one

visitor of a red and white bull, wild-eyed and flicking its tail, serving as

the artists' model.

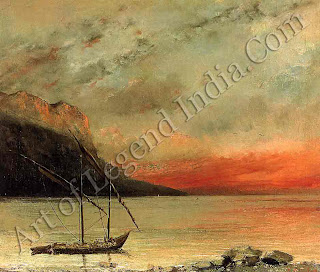

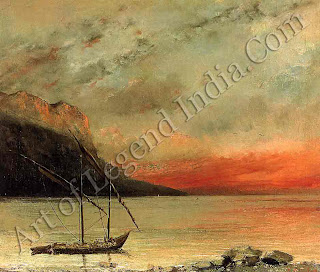

This

freshness of approach was evident not only in Courbet's choice of

subject-matter, but also in his use of paint. Even his sternest critics did not

dispute his technical skill and, in particular, his ability to capture the

richness of material surfaces. Courbet painted rapidly and with extraordinary

dexterity. And he pioneered the use of a trowel-shaped palette knife, called a

couteati anglais (English knife), which was long and flexible, allowing a

surprising delicacy of touch. He employed coarse paints, often mixed with sand

to stress their materiality, and applied very thickly on to the canvas. Because

of this, his pictures contrasted dramatically with the smooth, highly finished

paintings usually shown at the Salon. In his landscapes, Courbet opted for a

blunt, non-picturesque approach, in defiance of the popular style, where a

well-ordered collection of natural features, each carefully linked to the next,

would draw the spectator into the scene. By contrast, Courbet sought to produce

a single, powerful image on the surface of the canvas. He built his forest

scenes around a dense, screen-like core, which prevented the eye from

penetrating inwards and forced it to linger on the surface.

This

shallow picture space is also used to great effect in group portraits like the

Burial where the figures run right across the surface of the vast canvas, with

a direct visual impact that was too powerful to be ignored.

Even

outside the act of painting, Courbet asserted his artistic independence by

taking the revolutionary step of exhibiting his own show, under his own terms

and by his reluctance to accept the role of teacher. In an open letter to his

students, he set out this philosophy, declaring that sincerity to oneself was

the key to all art and that with the aid of tradition and personal inspiration,

every artist had to be his own master.

Writer – Marshall

Cavendish

Yet the

methods that Courbet used to create his 'living art' were in some ways derived

from the art of the past. In many of his most famous canvases, he made

traditional use of secondary sources. For Burial at Ornans, for example, he

incorporated elements borrowed from popular prints of the day with portraits of

his family and neighbours; the model in The Studio was taken from a photograph,

and some of his landscapes were composites, built up from separate studies.

Yet the

methods that Courbet used to create his 'living art' were in some ways derived

from the art of the past. In many of his most famous canvases, he made

traditional use of secondary sources. For Burial at Ornans, for example, he

incorporated elements borrowed from popular prints of the day with portraits of

his family and neighbours; the model in The Studio was taken from a photograph,

and some of his landscapes were composites, built up from separate studies.  It was

partly for this reason that Courbet was so reticent about his own conventional

training and probably why he was so reluctant to take on students of his own.

When, for a very brief period in 1862, he was persuaded to run a studio, he was

determined that his pupils should not be tempted by their life-classes into

painting only nudes in heroic poses. Hence the spectacle which greeted one

visitor of a red and white bull, wild-eyed and flicking its tail, serving as

the artists' model.

It was

partly for this reason that Courbet was so reticent about his own conventional

training and probably why he was so reluctant to take on students of his own.

When, for a very brief period in 1862, he was persuaded to run a studio, he was

determined that his pupils should not be tempted by their life-classes into

painting only nudes in heroic poses. Hence the spectacle which greeted one

visitor of a red and white bull, wild-eyed and flicking its tail, serving as

the artists' model.

0 Response to "French Great Artist Gustave Courbet - The Shock of Reality "

Post a Comment