Monastic Life

Monastic Life

By the

15th century the monasteries had become notorious for their worldliness and

debauchery, yet there were some devout orders in which monks led austere lives

of study and prayer.

'They

cheat, steal, fornicate, and when they are at the end of their resources they

set up as saints and work miracles.' Such was the charge made against friars by

the 15th century Italian author Masuccio, and his opinion was shared by many of

his contemporaries.

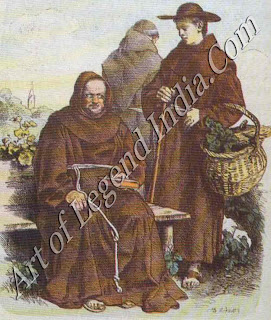

In the

growing secular and commercial atmosphere of Renaissance Florence, monastic

life appeared parasitic. The most virulent dislike was reserved for the friars

in the mendicant (begging) orders the Franciscans, Dominicans and Carmelites,

all of whom had settled in Florence during the 13th century.

But to

a large extent, it was the hypocritical flouting of the basic monastic rules of

poverty, chastity and obedience which inflamed the public. Contemporary records

make it clear that it was not unusual for friars and priests to carry weapons

and hunt, or to keep mistresses and father children.

But to

a large extent, it was the hypocritical flouting of the basic monastic rules of

poverty, chastity and obedience which inflamed the public. Contemporary records

make it clear that it was not unusual for friars and priests to carry weapons

and hunt, or to keep mistresses and father children.

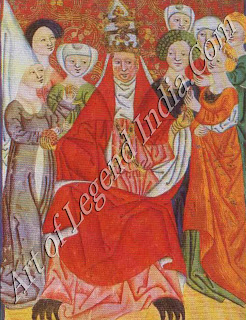

Obedience

to religious rules seemed equally lax in many convents of nuns. Masuccio went

so far as to claim: Some nuns are formally wedded to monks, with the

accompaniments of mass, a marriage contract and a liberal indulgence in food

and wine. The nuns afterward bring forth pretty little monks or else use means

to hinder that result'.

No

doubt exaggerated for satirical effect, Masuccio's claim nevertheless held more

than a grain of truth. Often, monasteries and nunneries were close enough for

members of the orders to mingle and to share beds. Monastery archives testify

to this fact with their volumes given over to the trials of cohabiting monks

and nuns. Immorality was so rife that rumours began to be heard in favour of

priests marrying.

No

doubt exaggerated for satirical effect, Masuccio's claim nevertheless held more

than a grain of truth. Often, monasteries and nunneries were close enough for

members of the orders to mingle and to share beds. Monastery archives testify

to this fact with their volumes given over to the trials of cohabiting monks

and nuns. Immorality was so rife that rumours began to be heard in favour of

priests marrying.

In

addition to this, the religious orders were openly becoming worldlier. They

courted the patronage of princes and businessmen, owned large amounts of land,

sold pardons and deathbed absolutions, and concerned themselves intimately with

the affairs of the people and political life. Some monks also took advantage of

the anonymity and sanctity their habits afforded them and acted as agents and

go-betweens in conspiracies and murder-plots.

POOR CANDIDATES

A

decline in monastic standards was almost inevitable at a time when candidates

were admitted too easily and for the wrong reasons. Many were the children of

impoverished noble families who paid a one-off sum to the monastery to secure a

respectable career for their offspring, and not all had true vocations for the

religious life. The level of learning was generally not high and many

candidates had no aptitude for study. However, there were those who pursued

lives of prayer, study and work, and monks who belonged to the well-endowed

monasteries in the great city states of Pisa, Milan and particularly Florence

were the privileged members of some of the best centres of learning in Europe.

Nowhere

are the extremes of monastic types more apparent than in the lives of the

Florentine painter-monks, Fra Angelico and Fra Filippo Lippi. In 1421 Lippi, an

orphan, was placed in the Carmelite priory in Florence. But his unsuitability

for such a life was shown by his subsequent trial for fraud, and his abduction

of a nun, Lucrezia, whom he later married and who bore him a son, Filippino,

who also became a painter.

In

marked contrast, Fra Angelico led a reverent life within the Dominican order,

earning for himself the title of Beato, meaning 'blessed one'. Although the

qualities of spirituality and grace that are found in his paintings may have

enhanced his reputation, his life in the Florentine monastery of San Marco was

certainly a devout one.

THE DOMINICANS

From

the early 13th century, the Dominican order had been based in the western part

of Florence, around the church of Sta Maria Novella. The Dominicans stressed

religious orthodoxy and obedience to the pope. They had a strong commitment to

learning as well as to preaching, I and set up studia generale, a form of

higher education catering not only for members of their shown order but for

secular students too. Similar establishments were founded by the Franciscans

and Augustinians in other parts of the city. The teachers came from within the

order, but were sent to study abroad at universities such as Paris and Bologna.

Dante, a pupil of the studio, is proof of the high standards of learning that

the system fostered.

From

the early 13th century, the Dominican order had been based in the western part

of Florence, around the church of Sta Maria Novella. The Dominicans stressed

religious orthodoxy and obedience to the pope. They had a strong commitment to

learning as well as to preaching, I and set up studia generale, a form of

higher education catering not only for members of their shown order but for

secular students too. Similar establishments were founded by the Franciscans

and Augustinians in other parts of the city. The teachers came from within the

order, but were sent to study abroad at universities such as Paris and Bologna.

Dante, a pupil of the studio, is proof of the high standards of learning that

the system fostered.

The

history of the Dominican monastery of San Marco demonstrates the close links

between political and business interests and religious life. Although

professing humanist ideas, Cosimo de' Medici the ruler of Florence was anxious

to keep his Christian life blameless. Apparently suffering from prickings of

conscience that 'certain portions of his wealth had not been righteously

gained', Cosimo was advised by the pope to use the money to extend the

monastery around the church of San Marco, which he had recently handed over to

the Observantist Dominicans, a reforming branch of the order. In this way,

Cosimo could 'unburden his soul'.

Work

began on the new monastery and library of San Marco in 1437. The plan followed

traditional monastic lines, with the rooms built around three sides of a

cloister, with the guest hospice, the chapter house and the refectory

downstairs, and the monks' study-cells, dormitories and the library on the

first floor. But the light, classical simplicity of the architecture set the

monastery apart from others in the city, and the library became a pattern for

subsequent Italian monasteries. When in 1444 Cosimo donated a collection of

over 400 Greek and Latin manuscripts to the library, San Marco became the

largest and most influential of the early public libraries in Italy.

The

second prior of San Marco was Antoninus Pierozzi, who took up his post in 1439

and later authorized the decoration of the monastery's cell walls with the

wonderful frescoes of Fra Angelico. He later became Archbishop of Florence and

was made a saint at his death. His life was led according to the austerest

Dominican precepts; he gave a third of his income to charity and, as was the

monastic rule, provided food and sustenance to the Florentine poor and the

swarms of beggars who visited the monastery with their children. He also

founded an organization for the poveri vergognosi, the 'embarassed poor', who

were too ashamed to let their poverty be known publicly.

Antonino's

moral guidance also led to a drive to reform both the Florentine clergy and

monastic discipline within his own monastery. Here the principles laid down for

all Dominican friars were strictly observed, with the celebration of the six

liturgical offices, each lasting for three hours, forming the basis of the

monastic day.

In most

orders there was little privacy, with monks sleeping in large dormitories.

Because of the Dominican emphasis on learning, individual cells had developed,

where members could obtain a degree of privacy and silence for studying. These

were generally small rooms arranged on each side of a central corridor, from

which the interior of each cell was visible.

MEALS AND RECREATION

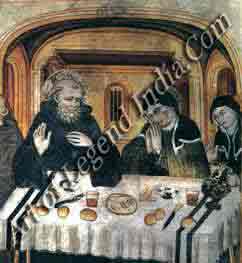

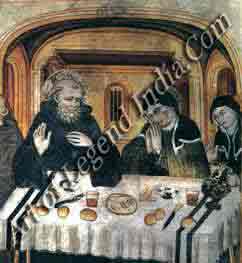

Meals

were frugal, although the Florentine orders were well provided by their

farmlands in Tuscany, which supplied them with wine, wheat, beer and oil. Two

meals a day were eaten in summer (from Easter to mid-September) and generally

only one in winter. Extra food was allowed on feast days but no meat was served

in the monastery. Wine or beer was commonly served at meals, although it was

frequently withdrawn as a penance. Silence was observed at meals and for most

of the day.

Meals

were frugal, although the Florentine orders were well provided by their

farmlands in Tuscany, which supplied them with wine, wheat, beer and oil. Two

meals a day were eaten in summer (from Easter to mid-September) and generally

only one in winter. Extra food was allowed on feast days but no meat was served

in the monastery. Wine or beer was commonly served at meals, although it was

frequently withdrawn as a penance. Silence was observed at meals and for most

of the day.

After

the midday meal came a brief period of recreation, when friars could talk or

exercise on the gardens. Relaxation did not include running, playing games,

laughing loudly or singing especially singing vulgar songs although by the

Renaissance, many warnings for this kind of behaviour are recorded.

DECLINING STANDARDS

After

the death of Antonino, the standards at San Marco declined until later in the

century, when the puritannical zeal of a yet more famous prior, the martyr

Savonarola, brought a new wave of reforms, not only within the walls of the

monastery but throughout the whole of Florence.

Writer – Marshall

Cavendish

Monastic Life

Monastic Life But to

a large extent, it was the hypocritical flouting of the basic monastic rules of

poverty, chastity and obedience which inflamed the public. Contemporary records

make it clear that it was not unusual for friars and priests to carry weapons

and hunt, or to keep mistresses and father children.

But to

a large extent, it was the hypocritical flouting of the basic monastic rules of

poverty, chastity and obedience which inflamed the public. Contemporary records

make it clear that it was not unusual for friars and priests to carry weapons

and hunt, or to keep mistresses and father children.  No

doubt exaggerated for satirical effect, Masuccio's claim nevertheless held more

than a grain of truth. Often, monasteries and nunneries were close enough for

members of the orders to mingle and to share beds. Monastery archives testify

to this fact with their volumes given over to the trials of cohabiting monks

and nuns. Immorality was so rife that rumours began to be heard in favour of

priests marrying.

No

doubt exaggerated for satirical effect, Masuccio's claim nevertheless held more

than a grain of truth. Often, monasteries and nunneries were close enough for

members of the orders to mingle and to share beds. Monastery archives testify

to this fact with their volumes given over to the trials of cohabiting monks

and nuns. Immorality was so rife that rumours began to be heard in favour of

priests marrying.  From

the early 13th century, the Dominican order had been based in the western part

of Florence, around the church of Sta Maria Novella. The Dominicans stressed

religious orthodoxy and obedience to the pope. They had a strong commitment to

learning as well as to preaching, I and set up studia generale, a form of

higher education catering not only for members of their shown order but for

secular students too. Similar establishments were founded by the Franciscans

and Augustinians in other parts of the city. The teachers came from within the

order, but were sent to study abroad at universities such as Paris and Bologna.

Dante, a pupil of the studio, is proof of the high standards of learning that

the system fostered.

From

the early 13th century, the Dominican order had been based in the western part

of Florence, around the church of Sta Maria Novella. The Dominicans stressed

religious orthodoxy and obedience to the pope. They had a strong commitment to

learning as well as to preaching, I and set up studia generale, a form of

higher education catering not only for members of their shown order but for

secular students too. Similar establishments were founded by the Franciscans

and Augustinians in other parts of the city. The teachers came from within the

order, but were sent to study abroad at universities such as Paris and Bologna.

Dante, a pupil of the studio, is proof of the high standards of learning that

the system fostered.  Meals

were frugal, although the Florentine orders were well provided by their

farmlands in Tuscany, which supplied them with wine, wheat, beer and oil. Two

meals a day were eaten in summer (from Easter to mid-September) and generally

only one in winter. Extra food was allowed on feast days but no meat was served

in the monastery. Wine or beer was commonly served at meals, although it was

frequently withdrawn as a penance. Silence was observed at meals and for most

of the day.

Meals

were frugal, although the Florentine orders were well provided by their

farmlands in Tuscany, which supplied them with wine, wheat, beer and oil. Two

meals a day were eaten in summer (from Easter to mid-September) and generally

only one in winter. Extra food was allowed on feast days but no meat was served

in the monastery. Wine or beer was commonly served at meals, although it was

frequently withdrawn as a penance. Silence was observed at meals and for most

of the day.

0 Response to "Italian Great Artist Fra Angelico - Monastic Life"

Post a Comment