The Legend of Henry VIII

Henry

VIII inherited from his father a country that was prosperous and stable after

decades of civil war. He made his own image a crucial factor in strengthening

still further the power of the monarchy.

During

the reign of King Henry VIII (1509-47), Englishmen had their first significant

contacts with the Renaissance, the new outlook in life and art that had first

appeared in Italy and was gradually spreading throughout Europe. Henry himself

welcomed Renaissance artists such as Holbein and the Italian sculptor Pietro

Torrigiano, and patronised the 'New Learning' of scholar-writers such as the

Dutchman Erasmus and England's own Sir Thomas More. In the early part of his

reign Henry enjoyed playing the part of the ideal Renaissance monarch handsome,

cultivated, extravagant, warlike, and above all the absolute monarch of his

realm. With age, corpulence and ulcers, much of the King's glamour disappeared,

but his mastery in the state had become greater than ever. Henry, the man of

many wives and many executions, was the first 'Tudor despot'.

Henry

was the second of the Tudor monarchs. His father, Henry VII (1457-1509),

founded the dynasty by defeating Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485.

This brought to an end the thirty-year Wars of the Roses, during which

aristocratic factions had made and unmade kings with alarming frequency. Henry

VII was not a colourful figure like his son and other descendants, but he

commanded respect and succeeded in restoring royal authority. Astute,

persistent, hardworking and a first-rate businessman, he made his nobles keep

the peace and greatly enriched the royal coffers.

Henry

VIII was more erratic and lavish in his spending than his father, whose

carefully accumulated fortune he soon frittered away. But he maintained the

policy of strengthening the Crown, both practically and symbolically. Like his

father, he employed 'new men' from outside the nobility men whose loyalty could

be relied on, since they owed everything to him. At the same time, Henry made

the court a magnet for the nobility, encouraging them to compete for decorative

offices and signs of the king's favour, SO that they became psychologically

dependent on him and spent less time on the estates which constituted their

bases of power. Splendid ceremonies emphasized the special character of the

king; and a small but significant fact Henry ceased to be addressed as 'Your

Grace', like previous monarchs, and became the first to be called 'Your

Majesty'.

Henry

VIII was more erratic and lavish in his spending than his father, whose

carefully accumulated fortune he soon frittered away. But he maintained the

policy of strengthening the Crown, both practically and symbolically. Like his

father, he employed 'new men' from outside the nobility men whose loyalty could

be relied on, since they owed everything to him. At the same time, Henry made

the court a magnet for the nobility, encouraging them to compete for decorative

offices and signs of the king's favour, SO that they became psychologically

dependent on him and spent less time on the estates which constituted their

bases of power. Splendid ceremonies emphasized the special character of the

king; and a small but significant fact Henry ceased to be addressed as 'Your

Grace', like previous monarchs, and became the first to be called 'Your

Majesty'.

MOCKING THE POPE

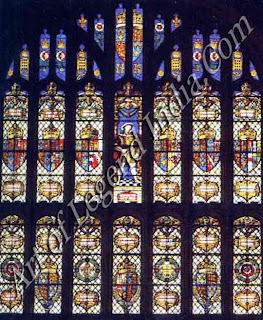

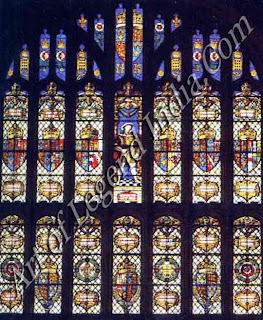

Hampton

Court became Henry's favourite residence and he lavished money on it. His

additions included the majestic Great Hall and a court for the game of 'real

tennis' (that is, 'royal tennis'), a forerunner of the modern game. The palace

was the scene of two of his weddings (to Catherine Howard and Catherine Parr)

and his son Edward was born there in 1537.

The

minister who organized all this for Henry was Thomas Cromwell, another 'new

man', the son of a brewer and blacksmith. He developed the Tudor administration

into something that resembled a permanent and specialized civil service. Wales

was integrated into the English system in the mid-1530s, and later on Henry

promoted himself from 'Lord' to King of Ireland.

But the

king or his advisers knew that the drastic religious changes he had introduced

when he separated England from the Church of Rome were bound to confuse and

alienate many people. To counteract this, they launched a large-scale

propaganda campaign in the 1530s that was clearly intended to reach all

classes. Plays and pageants explained the changes, mocked the pope and played

on popular anti-clericalism; there was even a mock-battle on the Thames between

papal and royal barges which ended with the 'pope' and his 'cardinals' getting

a good ducking. Lawyers and moralists published pamphlets and books that

exploited the rising tide of nationalism, making loyalty to England and the

king the supreme value. And efforts were made to raise the status of kingship

even further.

A PASSION FOR BUILDING

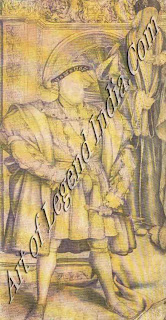

Now

head of the Church, Henry was presented as, in effect, a semi-divine being.

When Holbein, normally so perceptive and realistic, was called on to paint the

King's portrait, he represented him as a cold and fearful icon rather than a

man; or, as a contemporary put it, 'not only a king to be obeyed, but an idol

to be worshipped'. In another of Holbein's works a miniature Henry appears as

Solomon under an inscription reading 'Blessed be the Lord thy God, which delighted

in thee to set thee on his throne, to be King for the Lord thy God.' And, for

more popular consumption, Henry was shown on the engraved titlepage of

Cranmer's Great Bible, enthroned like a divinity while he distributed 'the word

of God' and multitudes below shouted 'Vivat Rex'! (Long live the King!).

The

royal idol also advertised his greatness by building on a large and lavish

scale. Wolsey's suinptous houses at Hampton Court and York Place (later

Whitehall) were taken over and expanded into great royal palaces, and in Surrey

a palace with a fairytale skyline, Nonsuch, was built from scratch to rival the

famous French Renaissance château of Chambord. Nonsuch and York Place are now

destroyed, but Henry's portions of Hampton Court remain among the glories of

English architecture.

The

royal idol also advertised his greatness by building on a large and lavish

scale. Wolsey's suinptous houses at Hampton Court and York Place (later

Whitehall) were taken over and expanded into great royal palaces, and in Surrey

a palace with a fairytale skyline, Nonsuch, was built from scratch to rival the

famous French Renaissance château of Chambord. Nonsuch and York Place are now

destroyed, but Henry's portions of Hampton Court remain among the glories of

English architecture.

THE BREAK WITH ROME

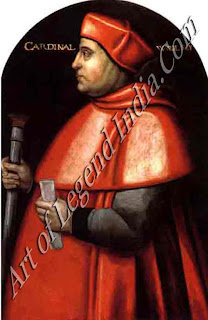

During

Holbein's first visit to England (1526- 28), Henry was in his mid thirties but

still had something of the playboy about him. Tall and powerfully built, he

revelled in his athletic skills, and was also an accomplished musician.

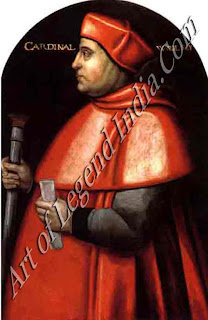

Effective power was exercised by Cardinal Wolsey, a 'new man' (reputedly the

son of a butcher) who ran the government while the King jousted and hunted.

By the

time Holbein returned in 1532, every-thing had changed. Wolsey was dead, and

the king involved himself far more closely with policy. Wolsey was doomed

mainly because he failed to obtain a divorce for the king. After many years of

marriage to Catherine of Aragon, Henry had only a single child, the Princess

Mary. This seemed to threaten the entire Tudor achievement, since everybody

knew that no woman could govern properly, and that chaos, civil war or foreign

occupation would inevitably result. (Of course Mary, and later Queen Elizabeth,

were to show that 'everybody' was quite wrong).

By the

time Holbein returned in 1532, every-thing had changed. Wolsey was dead, and

the king involved himself far more closely with policy. Wolsey was doomed

mainly because he failed to obtain a divorce for the king. After many years of

marriage to Catherine of Aragon, Henry had only a single child, the Princess

Mary. This seemed to threaten the entire Tudor achievement, since everybody

knew that no woman could govern properly, and that chaos, civil war or foreign

occupation would inevitably result. (Of course Mary, and later Queen Elizabeth,

were to show that 'everybody' was quite wrong).

Desperate

for a male heir, Henry convinced himself that his marriage was invalid (for

Catherine had been the wife of his dead brother), and put his case to Pope

Clement VII. The situation was complicated by politics as well as theology (the

Pope played for time, since he was a virtual prisoner of Catherine's nephew,

the Emperor Charles V), and by Henry's love for Anne Boleyn,. who insisted that

he prove it by marrying her. Eventually Henry took matters into his own hands,

breaking with the Pope, making himself Supreme Head of the English Church, and

marrying Anne.

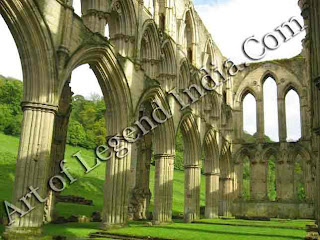

Ironically,

then, the weakness in the Tudors' political system the succession brought about

a series of events that tremendously enhanced the royal authority. In effect,

Henry became pope as well as king; and the Royal Supremacy which excluded papal

power from England also ended the independence of the English Church, whose

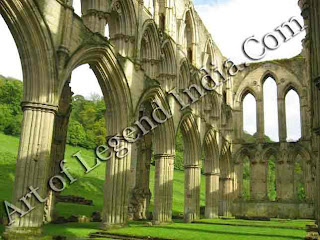

courts at last became answerable to the civil power. Furthermore, the vast

wealth of the medieval church restored the royal finances when Henry dissolved

(that is, closed down and took over) the thousand or so English monasteries,

confiscating their accumulated wealth and extensive lands.

A GODLIKE FIGURE

Henry's

reign was far from an unqualified success. He had six wives, executed two of

them, and had still not produced a healthy male heir. When invasion threatened,

possible claimants to the throne were removed by judicial murder. Ill-judged

wars bankrupted the Crown, and tampering with the currency seriously damaged

the economy. Yet Henry's propaganda campaign worked. We still see the King

through Holbein's eyes, as a splendid, godlike figure; and the strengthened

Tudor state bequeathed by Henry to his successors stood the test of revolutions

and § counter-revolutions over the three turbulent a reigns that followed.

Writer – Marshall

Cavendish

Henry

VIII was more erratic and lavish in his spending than his father, whose

carefully accumulated fortune he soon frittered away. But he maintained the

policy of strengthening the Crown, both practically and symbolically. Like his

father, he employed 'new men' from outside the nobility men whose loyalty could

be relied on, since they owed everything to him. At the same time, Henry made

the court a magnet for the nobility, encouraging them to compete for decorative

offices and signs of the king's favour, SO that they became psychologically

dependent on him and spent less time on the estates which constituted their

bases of power. Splendid ceremonies emphasized the special character of the

king; and a small but significant fact Henry ceased to be addressed as 'Your

Grace', like previous monarchs, and became the first to be called 'Your

Majesty'.

Henry

VIII was more erratic and lavish in his spending than his father, whose

carefully accumulated fortune he soon frittered away. But he maintained the

policy of strengthening the Crown, both practically and symbolically. Like his

father, he employed 'new men' from outside the nobility men whose loyalty could

be relied on, since they owed everything to him. At the same time, Henry made

the court a magnet for the nobility, encouraging them to compete for decorative

offices and signs of the king's favour, SO that they became psychologically

dependent on him and spent less time on the estates which constituted their

bases of power. Splendid ceremonies emphasized the special character of the

king; and a small but significant fact Henry ceased to be addressed as 'Your

Grace', like previous monarchs, and became the first to be called 'Your

Majesty'.  The

royal idol also advertised his greatness by building on a large and lavish

scale. Wolsey's suinptous houses at Hampton Court and York Place (later

Whitehall) were taken over and expanded into great royal palaces, and in Surrey

a palace with a fairytale skyline, Nonsuch, was built from scratch to rival the

famous French Renaissance château of Chambord. Nonsuch and York Place are now

destroyed, but Henry's portions of Hampton Court remain among the glories of

English architecture.

The

royal idol also advertised his greatness by building on a large and lavish

scale. Wolsey's suinptous houses at Hampton Court and York Place (later

Whitehall) were taken over and expanded into great royal palaces, and in Surrey

a palace with a fairytale skyline, Nonsuch, was built from scratch to rival the

famous French Renaissance château of Chambord. Nonsuch and York Place are now

destroyed, but Henry's portions of Hampton Court remain among the glories of

English architecture.  By the

time Holbein returned in 1532, every-thing had changed. Wolsey was dead, and

the king involved himself far more closely with policy. Wolsey was doomed

mainly because he failed to obtain a divorce for the king. After many years of

marriage to Catherine of Aragon, Henry had only a single child, the Princess

Mary. This seemed to threaten the entire Tudor achievement, since everybody

knew that no woman could govern properly, and that chaos, civil war or foreign

occupation would inevitably result. (Of course Mary, and later Queen Elizabeth,

were to show that 'everybody' was quite wrong).

By the

time Holbein returned in 1532, every-thing had changed. Wolsey was dead, and

the king involved himself far more closely with policy. Wolsey was doomed

mainly because he failed to obtain a divorce for the king. After many years of

marriage to Catherine of Aragon, Henry had only a single child, the Princess

Mary. This seemed to threaten the entire Tudor achievement, since everybody

knew that no woman could govern properly, and that chaos, civil war or foreign

occupation would inevitably result. (Of course Mary, and later Queen Elizabeth,

were to show that 'everybody' was quite wrong).

0 Response to "German Great Artist Hans Holbein - The Legend of Henry VIII "

Post a Comment