The Fleeting Impression

Monet

painted in the open air with a speed and fervour no earlier artist had

approached. But as he grew older, he saw the need to work more in his studio,

to refine and perfect his paintings.

Monet

is often considered the greatest and most typical of the Impressionists. This judgment

reflects not only the quality of his work, but also his wholehearted dedication

to the ideals of Impressionism throughout his mature -fife. In particular, he

was committed to the Impressionist practice of painting out of doors. This in

itself was not new, but Monet made it an article of faith.

None of

his predecessors had worked out-of-doors to the same ambitious scale. In the

early 19th century, for example, John Constable had often made sketches in oils

outdoors, but only as preparatory studies for larger paintings. And Boudin and

Jongkind, the two artists who had the most important influence on Monet's early

work, also worked on a fairly small scale. Monet differed from these painters

both in his conviction and in his ambitions. He made outdoor painting not just

a basis for further elaboration, but the central feature of his huge output.

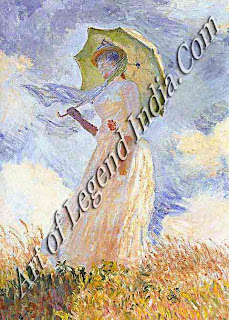

Monet's

declared aim was to catch the passing impressions of light and atmosphere, 'the

most fleeting effects', as he called them, and in his dedication to this goal

he took measures that often had an element of farce about them. In 1866-7 he

painted one of his most famous works, Women in the Garden, a canvas more than

eight feet high, and to enable him to paint all the picture out-of-doors, he

had a trench dug so the canvas could be raised or lowered by pulleys to the

required height.

Monet's

declared aim was to catch the passing impressions of light and atmosphere, 'the

most fleeting effects', as he called them, and in his dedication to this goal

he took measures that often had an element of farce about them. In 1866-7 he

painted one of his most famous works, Women in the Garden, a canvas more than

eight feet high, and to enable him to paint all the picture out-of-doors, he

had a trench dug so the canvas could be raised or lowered by pulleys to the

required height.

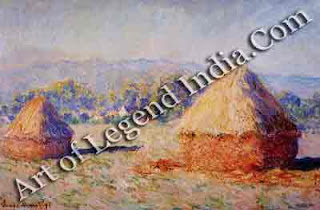

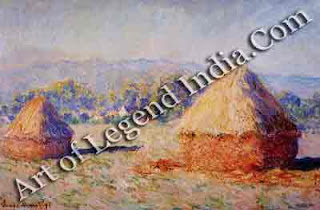

Much

later in his career, when he was working on a series of paintings such as his

Haystacks, his step-daughter Blanche Hoschede-Monet used a wheelbarrow to carry

his unfinished paintings around the fields with him; when the light changed

perceptibly, Monet would switch to another canvas that matched the new

conditions.

BRAVING THE ELEMENTS

Bad

weather did not weaken his determination to capture the effects he wanted. One

observer described him working on the Normandy coast in 1885: With water

streaming under his cape, he painted the storm amid the swirl of the salt

water. He had between his knees two or three canvases, which took their place

on his easel one after another, each for a few minutes at a time. On the stormy

sea different light effects appeared. The painter watched for each of these

effects, a slave to the comings and goings of the light, laying down his brush

when the effect was gone, placing at his feet the unfinished canvas, ready to

resume work upon the return of a vanished impression.

Bad

weather did not weaken his determination to capture the effects he wanted. One

observer described him working on the Normandy coast in 1885: With water

streaming under his cape, he painted the storm amid the swirl of the salt

water. He had between his knees two or three canvases, which took their place

on his easel one after another, each for a few minutes at a time. On the stormy

sea different light effects appeared. The painter watched for each of these

effects, a slave to the comings and goings of the light, laying down his brush

when the effect was gone, placing at his feet the unfinished canvas, ready to

resume work upon the return of a vanished impression.

Such

accounts of Monet at work part-heroic, part-absurd illustrate what he and the

other Impressionists found was the greatest drawback to their new approach to

painting: the effects in nature change so quickly that the more sensitive air

artist is to them, the less time he can spend on a picture before any

particular effect has gone. Referring to his haystack series in October 1890,

Monet wrote: 'I really am working terribly hard, struggling with a series of

different effects, but at this time of year the sun sets so quickly that I

can't keep up with it.' To overcome this problem Monet began to work more and

more in the studio to re-touch or revise his paintings. But publicly he liked

to maintain his image as an outdoor painter.

PAINTING AT SPEED

Monet

developed a free and spontaneous painting technique which enabled him to work

at speed. His brushwork is remarkably flexible and varied, sometimes broad and

sweeping, sometimes fragmented and sparkling. Occasionally he used the handle

of the brush to scratch through the paint surface and create a more broken,

textured effect. His last paintings, the great series representing the

waterlilies in his garden at Givemy, were executed more slowly than his earlier

works and many of them have a richly encrusted surface, the paint dragged and

superimposed, layer upon shimmering layer.

Monet

developed a free and spontaneous painting technique which enabled him to work

at speed. His brushwork is remarkably flexible and varied, sometimes broad and

sweeping, sometimes fragmented and sparkling. Occasionally he used the handle

of the brush to scratch through the paint surface and create a more broken,

textured effect. His last paintings, the great series representing the

waterlilies in his garden at Givemy, were executed more slowly than his earlier

works and many of them have a richly encrusted surface, the paint dragged and

superimposed, layer upon shimmering layer.

Paul

Cezanne, a landscape painter of equal stature, declared that Monet was 'only an

eye, but, my God, what an eye!' Many of Monet's own observations seem to bear

out that this was the way he thought of himself. He told a pupil that 'he

wished he had been born blind and then suddenly regained his sight, so that he

would have begun to paint without knowing what the objects were that he saw

before him'. And he advised 'When you go out to paint, try to forget what

objects you have in front of you, a tree, a field,.. Merely think, here is a

little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and

paint it just as it looks to you, the exact colour and shape, until it gives

your own naive impression of the scene.'

But no

artist simply reproduces what he sees in front of him, and although Monet might

strive to be objective, he was never impersonal. His increasing reliance on

studio work shows that he realized that his art consisted not merely in

observing and recording, but in finding a pictorial equivalent in opaque paint

on a two-dimensional surface for the infinitely varied effects of light. And as

with all great art, there is a dimension to Monet's work that ultimately evades

analysis or explanation. His great series of waterlily paintings, in

particular, are the product not simply of an exceptionally keen eye and an

unerring hand, but also of a poetic spirit.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

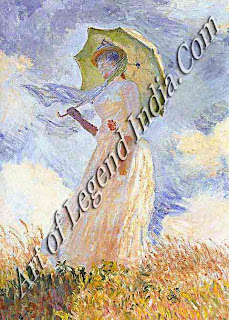

Monet's

declared aim was to catch the passing impressions of light and atmosphere, 'the

most fleeting effects', as he called them, and in his dedication to this goal

he took measures that often had an element of farce about them. In 1866-7 he

painted one of his most famous works, Women in the Garden, a canvas more than

eight feet high, and to enable him to paint all the picture out-of-doors, he

had a trench dug so the canvas could be raised or lowered by pulleys to the

required height.

Monet's

declared aim was to catch the passing impressions of light and atmosphere, 'the

most fleeting effects', as he called them, and in his dedication to this goal

he took measures that often had an element of farce about them. In 1866-7 he

painted one of his most famous works, Women in the Garden, a canvas more than

eight feet high, and to enable him to paint all the picture out-of-doors, he

had a trench dug so the canvas could be raised or lowered by pulleys to the

required height.  Bad

weather did not weaken his determination to capture the effects he wanted. One

observer described him working on the Normandy coast in 1885: With water

streaming under his cape, he painted the storm amid the swirl of the salt

water. He had between his knees two or three canvases, which took their place

on his easel one after another, each for a few minutes at a time. On the stormy

sea different light effects appeared. The painter watched for each of these

effects, a slave to the comings and goings of the light, laying down his brush

when the effect was gone, placing at his feet the unfinished canvas, ready to

resume work upon the return of a vanished impression.

Bad

weather did not weaken his determination to capture the effects he wanted. One

observer described him working on the Normandy coast in 1885: With water

streaming under his cape, he painted the storm amid the swirl of the salt

water. He had between his knees two or three canvases, which took their place

on his easel one after another, each for a few minutes at a time. On the stormy

sea different light effects appeared. The painter watched for each of these

effects, a slave to the comings and goings of the light, laying down his brush

when the effect was gone, placing at his feet the unfinished canvas, ready to

resume work upon the return of a vanished impression.  Monet

developed a free and spontaneous painting technique which enabled him to work

at speed. His brushwork is remarkably flexible and varied, sometimes broad and

sweeping, sometimes fragmented and sparkling. Occasionally he used the handle

of the brush to scratch through the paint surface and create a more broken,

textured effect. His last paintings, the great series representing the

waterlilies in his garden at Givemy, were executed more slowly than his earlier

works and many of them have a richly encrusted surface, the paint dragged and

superimposed, layer upon shimmering layer.

Monet

developed a free and spontaneous painting technique which enabled him to work

at speed. His brushwork is remarkably flexible and varied, sometimes broad and

sweeping, sometimes fragmented and sparkling. Occasionally he used the handle

of the brush to scratch through the paint surface and create a more broken,

textured effect. His last paintings, the great series representing the

waterlilies in his garden at Givemy, were executed more slowly than his earlier

works and many of them have a richly encrusted surface, the paint dragged and

superimposed, layer upon shimmering layer.

0 Response to " French Great Artist Cloud Monet - The Fleeting Impression"

Post a Comment