Annibale`s Bologna

Annibale`s Bologna

A

flourishing centre for the arts, Bologna was renowned for its colourful

festivals and gastronomic excellence. But underlying this 'prosperity' there

was widespread poverty and public unrest.

During

the last three decades of the 16th century, when the Carracci were at the

height of their activity, the busy and populous city of Bologna was one of the

most important cultural and economic centres in Europe. In 1587, the city's

population numbered 72,000, a level which was not reached again until 1791;

industry and commerce were slowly expanding and the ancient university

continued to prosper, attracting such influential scholars as Ulisse

Aldrovandi. In 1582, the city's importance as a centre of religious life was

formally acknowledged when Pope Gregory XIII created Bologna an archbishopric.

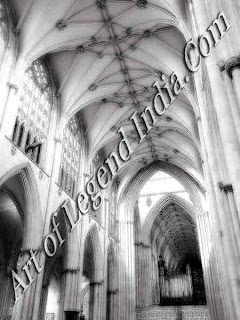

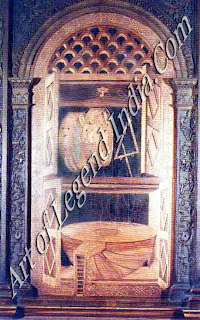

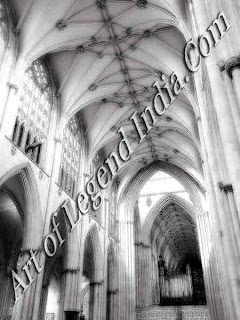

Most

important of all, the late 16th century saw an unprecedented flowering of

activity in the arts. The Carracci's Accademia degli Incamminati, which established

Bologna as a leading centre of painting in Europe was just one among a host of

cultural and scientific societies which sprang up in the city. Bologna's church

of San Petronio, one of the largest in the world, was renowned as a centre of

musical activity. Its unusual size and superb acoustics encouraged the

employment of massive groups of musicians, whose activities were to play an

important part in the development of the Baroque concerto form. At the same

time, the cappella musicale, or music academy, saw the emergence of a stream of

talented composers.

Most

important of all, the late 16th century saw an unprecedented flowering of

activity in the arts. The Carracci's Accademia degli Incamminati, which established

Bologna as a leading centre of painting in Europe was just one among a host of

cultural and scientific societies which sprang up in the city. Bologna's church

of San Petronio, one of the largest in the world, was renowned as a centre of

musical activity. Its unusual size and superb acoustics encouraged the

employment of massive groups of musicians, whose activities were to play an

important part in the development of the Baroque concerto form. At the same

time, the cappella musicale, or music academy, saw the emergence of a stream of

talented composers.

The

city's prosperity was largely the result of a long period of internal peace. In

1512, Pope Julius II had finally expelled from the city the ruling family of

Bentivoglio, and reclaimed Bologna as part of the Papal States. From that time

onwards, the city was governed jointly by an elected Senate of 40 men, drawn

from the local nobility, and a resident papal legate, or Legato. This unusual

form of government had its drawbacks, but it ensured a state of relative

tranquillity, and contributed to the distinctive character of the city's public

life.

The

city's prosperity was largely the result of a long period of internal peace. In

1512, Pope Julius II had finally expelled from the city the ruling family of

Bentivoglio, and reclaimed Bologna as part of the Papal States. From that time

onwards, the city was governed jointly by an elected Senate of 40 men, drawn

from the local nobility, and a resident papal legate, or Legato. This unusual

form of government had its drawbacks, but it ensured a state of relative

tranquillity, and contributed to the distinctive character of the city's public

life.

In

reality, the power of the Senate was considerably restricted by the presence

and authority of the Legato. Outwardly however, the senators attempted to create

the impression that they were successfully protecting the autonomy of the

Bolognese republic from the tyranny of Papalrule. The Carracci's frescoes of

the story of Romulus and Remus in the Palazzo Magnani, painted at the time when

the Magnani family were readmitted to the Senate after their exclusion by Pope

Leo X, can be seen as one expression of this republican spirit.

In

public, the senators surrounded themselves with all the trappings of status and

power, living lives of ostentatious luxuiy. Despite the passing of numerous

sumptuary laws, they dressed in the finest clothes and held endless banquets.

To reinforce their image, they organized festivals, tournaments and jousts. The

two-monthly election of the Gonfaloitiere di Giustizia (standard-bearer of

justice) was marked by an elaborate ceremony, accompanied by regular

processions and feasts. These sumptuous festivities, surpassed in extravagance

by few cities in Europe, combined with other religious celebrations to give

Bologna an unusually active and colourful public life.

GASTRONOMIC INDULGENCE

The

love of luxury and good living, and particularly of good food, was not confined

to the nobility. According to contemporary historians, the common people were

also given to bouts of over-indulgence, and feasted extensively at the end of

the week 'consuming in one day alone what they had earned with the sweat of

six'.

The

love of luxury and good living, and particularly of good food, was not confined

to the nobility. According to contemporary historians, the common people were

also given to bouts of over-indulgence, and feasted extensively at the end of

the week 'consuming in one day alone what they had earned with the sweat of

six'.

Bologna

has long been renowned as a centre of fine cuisine, and even today is known as

the gastronomic centre of Italy. Located in one of the most fertile regions of

the country, Bologna produces a cuisine which is rich in dairy products and

high quality meats. Best known for the invention of rapt, the rich meat sauce

which forms the basis of spaghetti bolognaise, the city can also claim to have

invented a number of other pasta dishes, such as lasagne and tortellini.

The

prosperity of Bologna was perhaps most dearly reflected in the extensive

building boom which began around the second decade of the century, and which

transformed the city into one of the most beautiful and richly varied in Italy.

The bustling medieval streets, with their distinctive covered arcades, became

punctuated by elegant new churches and palaces, based largely on contemporary

Roman models. 1562 saw the beginning of the Archiginnasio, an imposing new

building designed to bring together the scattered faculties of the University.

Two years later, the medieval Piazza Maggiore, the heart of city life, was

embellished by the construction of the adjacent Piazza del Nettuno, with its

spectacular bronze fountain by the sculptor Giambologna. Senators vied with

each other in constructing magnificent palaces with elaborate facades, as

concrete symbols of their power. And new areas of the city were built up within

the 13th-century walls, to accommodate the growing population.

ENLIGHTENED REFORM

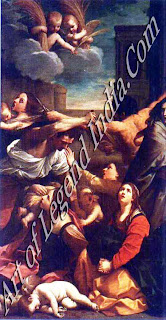

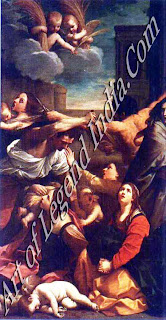

During

the years of the Carracci, Bologna was an important centre of religious reform.

Under the enlightened direction of its bishop, Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, the

proposals of the Council of Trent for the reinvigoration of the Catholic Church

were given new impetus. Paleotti founded a seminary for the training of

priests, insisting on the importance of the clergy in setting an example in

moral and religious behaviour. He also founded a number of charitable

institutions, including the Magistrato della Concordia, a committee of lay and

religious people designed to give free legal advice and assistance to citizens

of limited means.

During

the years of the Carracci, Bologna was an important centre of religious reform.

Under the enlightened direction of its bishop, Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, the

proposals of the Council of Trent for the reinvigoration of the Catholic Church

were given new impetus. Paleotti founded a seminary for the training of

priests, insisting on the importance of the clergy in setting an example in

moral and religious behaviour. He also founded a number of charitable

institutions, including the Magistrato della Concordia, a committee of lay and

religious people designed to give free legal advice and assistance to citizens

of limited means.

Despite

the surface festivity however, city life in Bologna had strong undercurrents of

violence and unrest. While the senators prospered, life for the common folk was

unremittingly harsh. The stagnating economy of the country as a whole,

exorbitant taxation and a series of poor harvests brought widespread poverty

and outbreaks of crime. 1588 saw the beginning of a series of food shortages

which left innumerable people dying of hunger in the city's streets. The same

year, a rise in the price of bread lead to riots in the city, culminating in

the arrest of over 100 bakers, butchers and rebels. Between 1587 and 1595 the

population fell by 13,000.

Despite

the surface festivity however, city life in Bologna had strong undercurrents of

violence and unrest. While the senators prospered, life for the common folk was

unremittingly harsh. The stagnating economy of the country as a whole,

exorbitant taxation and a series of poor harvests brought widespread poverty

and outbreaks of crime. 1588 saw the beginning of a series of food shortages

which left innumerable people dying of hunger in the city's streets. The same

year, a rise in the price of bread lead to riots in the city, culminating in

the arrest of over 100 bakers, butchers and rebels. Between 1587 and 1595 the

population fell by 13,000.

Public

order was also a serious problem. Although organized protest against conditions

was rare, theft and murder were common in the city, and contemporary chronicles

record each day's events as a bizzare combination of high festivities, ghastly

murders and public executions. The problem was most severe in the surrounding

countryside, where unemployed soldiers formed groups of bandits who looted,

raped and murdered. Often these bandits were sheltered by the nobility, who

used them to protect their own family and territorial interests. In 1585, the

Pope ordered the murder of the count and senator Giovanni Pepoli, who refused

to hand over a notorious bandit found on his territory; in deference to his

aristocratic status, the count was strangled with a silk noose. Among other

things, the count's execution was intended to serve as a warning to the

nobility, who tried to exert their authority in defiance of Rome.

By the

time Annibale Carracci died, the golden years of Bologna were over. The 17th

century witnessed the city's gradual decline, exacerbated by the calamitous

outbreak of plague in 1630, which left one quarter of the population dead. But

for Annibale, the city must have provided a sympathetic and stimulating

environment, with rich and varied patronage, active intellectual debate, and a

feast of luxurious spectacle.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

Most

important of all, the late 16th century saw an unprecedented flowering of

activity in the arts. The Carracci's Accademia degli Incamminati, which established

Bologna as a leading centre of painting in Europe was just one among a host of

cultural and scientific societies which sprang up in the city. Bologna's church

of San Petronio, one of the largest in the world, was renowned as a centre of

musical activity. Its unusual size and superb acoustics encouraged the

employment of massive groups of musicians, whose activities were to play an

important part in the development of the Baroque concerto form. At the same

time, the cappella musicale, or music academy, saw the emergence of a stream of

talented composers.

Most

important of all, the late 16th century saw an unprecedented flowering of

activity in the arts. The Carracci's Accademia degli Incamminati, which established

Bologna as a leading centre of painting in Europe was just one among a host of

cultural and scientific societies which sprang up in the city. Bologna's church

of San Petronio, one of the largest in the world, was renowned as a centre of

musical activity. Its unusual size and superb acoustics encouraged the

employment of massive groups of musicians, whose activities were to play an

important part in the development of the Baroque concerto form. At the same

time, the cappella musicale, or music academy, saw the emergence of a stream of

talented composers.  The

city's prosperity was largely the result of a long period of internal peace. In

1512, Pope Julius II had finally expelled from the city the ruling family of

Bentivoglio, and reclaimed Bologna as part of the Papal States. From that time

onwards, the city was governed jointly by an elected Senate of 40 men, drawn

from the local nobility, and a resident papal legate, or Legato. This unusual

form of government had its drawbacks, but it ensured a state of relative

tranquillity, and contributed to the distinctive character of the city's public

life.

The

city's prosperity was largely the result of a long period of internal peace. In

1512, Pope Julius II had finally expelled from the city the ruling family of

Bentivoglio, and reclaimed Bologna as part of the Papal States. From that time

onwards, the city was governed jointly by an elected Senate of 40 men, drawn

from the local nobility, and a resident papal legate, or Legato. This unusual

form of government had its drawbacks, but it ensured a state of relative

tranquillity, and contributed to the distinctive character of the city's public

life.  The

love of luxury and good living, and particularly of good food, was not confined

to the nobility. According to contemporary historians, the common people were

also given to bouts of over-indulgence, and feasted extensively at the end of

the week 'consuming in one day alone what they had earned with the sweat of

six'.

The

love of luxury and good living, and particularly of good food, was not confined

to the nobility. According to contemporary historians, the common people were

also given to bouts of over-indulgence, and feasted extensively at the end of

the week 'consuming in one day alone what they had earned with the sweat of

six'.  During

the years of the Carracci, Bologna was an important centre of religious reform.

Under the enlightened direction of its bishop, Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, the

proposals of the Council of Trent for the reinvigoration of the Catholic Church

were given new impetus. Paleotti founded a seminary for the training of

priests, insisting on the importance of the clergy in setting an example in

moral and religious behaviour. He also founded a number of charitable

institutions, including the Magistrato della Concordia, a committee of lay and

religious people designed to give free legal advice and assistance to citizens

of limited means.

During

the years of the Carracci, Bologna was an important centre of religious reform.

Under the enlightened direction of its bishop, Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, the

proposals of the Council of Trent for the reinvigoration of the Catholic Church

were given new impetus. Paleotti founded a seminary for the training of

priests, insisting on the importance of the clergy in setting an example in

moral and religious behaviour. He also founded a number of charitable

institutions, including the Magistrato della Concordia, a committee of lay and

religious people designed to give free legal advice and assistance to citizens

of limited means.  Despite

the surface festivity however, city life in Bologna had strong undercurrents of

violence and unrest. While the senators prospered, life for the common folk was

unremittingly harsh. The stagnating economy of the country as a whole,

exorbitant taxation and a series of poor harvests brought widespread poverty

and outbreaks of crime. 1588 saw the beginning of a series of food shortages

which left innumerable people dying of hunger in the city's streets. The same

year, a rise in the price of bread lead to riots in the city, culminating in

the arrest of over 100 bakers, butchers and rebels. Between 1587 and 1595 the

population fell by 13,000.

Despite

the surface festivity however, city life in Bologna had strong undercurrents of

violence and unrest. While the senators prospered, life for the common folk was

unremittingly harsh. The stagnating economy of the country as a whole,

exorbitant taxation and a series of poor harvests brought widespread poverty

and outbreaks of crime. 1588 saw the beginning of a series of food shortages

which left innumerable people dying of hunger in the city's streets. The same

year, a rise in the price of bread lead to riots in the city, culminating in

the arrest of over 100 bakers, butchers and rebels. Between 1587 and 1595 the

population fell by 13,000.

0 Response to "Italian Great Artist Annibale Carracci - Annibale`s Bologna"

Post a Comment