Showing posts with label Edward Hopper. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Edward Hopper. Show all posts

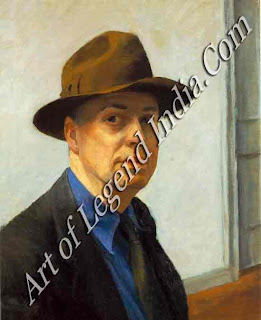

Born in

1882 in Nyack, near New York City, Edward Hopper is the greatest painter of

modern American life yet to emerge. He studied painting in New York with Robert

Henri, founder of the Ashcan school. On leaving college, he became a commercial

artist, only giving up this career at the age of 42 to become a full-time

artist. His interest in the effects of light was inspired by the

Impressionists, whose work Ix saw in Paris.

Hopper

found his very distinctive style in the 1920s and hardly changed it at all from

then on. Although he lived through the heyday of abstraction, Hopper remained

committed to the tradition of representational painting. Despite his late

start, America was quick to heap honours upon him. But he remained a very

private man, leading a life dedicated to painting with his wife, a fellow artist.

Hopper died in 1967, aged 84.

A tall,

laconic American, Edward Hopper liked to think of himself as a down-to-earth,

self-made man. He cherished his personal privacy, preferring silence to idle

chatter and artistic pretension.

Edward

Hopper grew up in middle-class small-town America. He was born on 22 July 1882

in Nyack, on the Hudson River just above New York City, the son of a

shopkeeper. He later described his father as 'an incipient intellectual who

never quite made it'. Edward was a solitary, bookish boy, who stood apart from

other children because of his abnormal height he suddenly grew to six feet at

the age of 12. The Hoppers' home overlooked the Hudson, and Eddie, as he was

then called, developed an early enthusiasm for boats, building his own cat-boat

at 15 with wood and tools supplied by his father.

Encouraged

by his mother, Hopper soon began to demonstrate a precocious talent for drawing

and, at the age of 17, he entered the Correspondence School of Illustrating in

New York. The following year he transferred to the New York School of Art,

studying first illustration and then painting. He found himself among an

exceptionally gifted generation of students, including famous names of the

future such as George Bellows and Rockwell Kent. His most t inspiring teacher

was Robert Henri, who fostered Y. in him a taste for subjects from everyday

urban life in the USA, as well as a respect for the great realist 3 masters of

the past; Velazquez, Goya, Daumier, Manet and Degas.

In

1906-7, with the money he saved from a brief, unsatisfying stint of work as an

illustrator with an advertising agency, and some help from his parents, Hopper

was able to realize his ambition of visiting the art capital of the world,

Paris. He stayed there for a few months and had an utterly un-bohemian time. His

parents made arrangements through the Baptist Church for him to stay with a

suitable bourgeois family, and he seems to have taken no interest in

avant-garde artists or their work. Instead, he came under the spell of

Impressionism, and developed an interest in capturing effects of light that was

to stay with him for his whole career as a painter. He was in Paris again in

1909 and 1910, after which he never again returned to Europe.

1882 born in Nyack, on the Hudson

River

1900-6 attends New York School

of Art, studying under Henri

1906-10 makes painting trips to

Paris

1913 sells painting in Armory

Show

1924 marries Jo Verstille Nivison;

abandons commercial work

1932 shows work in Whitney

Museum exhibition

1934 builds studio-house at Cape

Cod

1950/64 retrospective

exhibitions

1967 dies at studio in New

York

Back in

America, Hopper began to exhibit fairly regularly in New York, not at the

conservative National Academy of Design, which rejected his work, but at the

small anti-academic exhibitions organized by Robert Henri and other former

pupils at the MacDowell Club. But no critics or collectors took any serious

interest in him, and actually making a living from painting seemed out of the

question. Indeed, it is a measure of the doggedness that was part of Hopper's

character that he continued with art at all, only becoming a full-time painter

in 1924, at the age of 42.

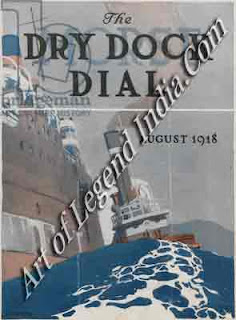

Until

that date, Hopper reluctantly supported himself by commercial design and fairly

routine illustrative jobs, working three days a week for advertising agencies

and strictly non-artistic journals such as The Farmer's Wife, The Country

Gentleman and System, the Magazine of Business. On occasion, he would eke out

his income by giving art lessons to children back home in Nyack, which he

disliked even more. He managed to sell a painting for $250 at the famous Armory

Show in 1913, and in 1918 won a prize of S300 from the US Shipping Board for a

propaganda poster entitled smash the Hun, but consistent success eluded him.

In

1913, Hopper took the studio at Washington Square North in New York City that

he occupied for the rest of his life, renting extra working and living space as

his finances allowed, yet never altering the bare, Spartan look of the place.

The habit of thrift instilled in him by his upbringing and deepened by the lean

early years of his career seems never to have left him, even after he became

quite wealthy. He would eat in the shabbiest restaurants and diners wear

clothes until they were threadbare and buy second-hand cars that he drove until

they gave up the ghost.

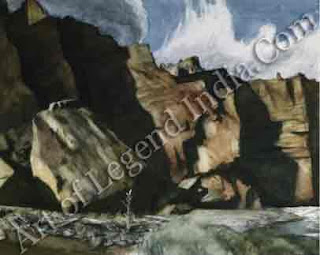

Hopper

had his first one-man exhibition in 1920, showing 16 oils painted in Paris and

during summer trips to the bleak, rocky Monhegan Island, Maine, about 300 miles

north-east of New York. Not a single work was sold, but the venue was an

auspicious one Whitney Studio Club. Founded by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney,

this was the forerunner of the famous Whitney Museum of American Art. The

museum was opened in 1931 and the same year bought Early Sunday Morning for its

permanent collection. Hopper was to be closely associated with the Whitney

throughout his life, showing new works in almost all the contemporary

exhibitions that were held there from 1932 onwards.

Unexpectedly,

Hopper made his long-awaited breakthrough in watercolour rather than in oils.

He only began using watercolour seriously in 1923, during a summer sketching

trip to Gloucester, Massachusetts. Later that year, the Brooklyn Museum

accepted six of the views he painted there for an exhibition; they were

favourably noticed by reviewers and the museum bought one of them for $100.

After a further successful watercolours' exhibition in 1924 at the gallery of

Frank K. M. Rehn, who became his dealer for the rest of his life, Hopper at

last felt sure enough of making a living to devote himself exclusively to

painting.

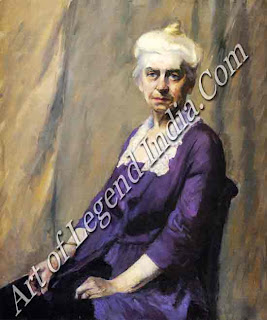

On 9

July 1924, he married Josephine (Jo) Verstille Nivison at the Baptist 'Eglise

Evangelique' in New York. They had been students together under Robert Henri

and had met by chance on visits to Maine and Massachusetts. Jo had trained as

an actress before she took up art, and was as talkative as Hopper was taciturn.

She was tiny, had a strong character, hated domestic duties and loved cats. Jo

was also possessive, and insisted that Hopper gave up drawing from the nude

model unless she modelled for him. As a result, many of the women in his

paintings, and all the nudes, are portraits of Jo.

It was

in the mid-1920s that Hopper forged the very distinctive style that we

associate with his name, and his work changed little from then on. The growing

reputation he enjoyed was reflected in the increasingly prestigious exhibitions

devoted to him: a one-man show at the Frank K. M. Rehn Gallery in 1929,

retrospectives at the Museum of Modern Art in 1933 and the Whitney Museum in 1950,

and a major retrospective at the Whitney in 1964 which toured afterwards to the

Art Institute of Chicago, the Detroit Institute of Arts and the City Art Museum

of St Louis.

Hopper

also accumulated prizes and honours. In 1932, the National Academy of Design

elected him an associate member, which he was pleased to refuse as the Academy

had refused him during his years of struggle and obscurity. The Pennsylvania

Academy of the Fine Arts awarded him the Temple Gold Medal in 1935, the first

of many such awards from American academies and museums. He won a series of

prizes at the Institute of Chicago, which in 1950 conferred upon him the

honorary degree of Doctor of Fine Arts; he was one of the four artists chosen

to represent the USA at the Venice Biennale of 1952; and in 1955, the American

Academy of Arts and Letters presented him with a Gold Medal for Painting.

By

1934, Hopper was able to build a studio-home away from it all at South Truro on

Cape Cod, where he and Jo stayed for part of almost every summer for the rest

of their lives. Success also enabled him to indulge his liking for travel it is

no accident that so many of Hopper's paintings depict hotels, motels and life

on the road and in 1941, he and Jo made a three-month grand tour by car across

the country to the West Coast and back. In 1943, there was a petrol shortage

that prevented them from driving anywhere, even up to Cape Cod, so they made a

train trip to Mexico instead, the first of a number of holidays they spent

there.

Hopper's

pleasures in life were never extravagant. He enjoyed the theatre, the cinema

and books. He was quite exceptionally well read and not only in English

literature: he was able to quote fluently from Goethe and the French Symbolist

poets in the original. He was especially fond of Symbolist verse, first

discovering it as a student and as late as 1951, giving Jo a volume of Rimbaud

for Christmas with an affectionate inscription in French. Indeed, there is a

strange melancholy about many of his paintings that the Symbolists, and most of

all Baudelaire, would surely have recognized.

In

spite of his rather sophisticated literary tastes, Hopper cultivated the public

persona of the down-to-earth self-made man who cared little for fancy ideas.

This may well have been a ploy designed to exempt him from seriously discussing

his own work. When interviewed, he usually refused to acknowledge any

intellectual or personal content in his pictures and claimed to be merely

working within the American Realist tradition, painting neither more nor less

than what he happened to see around him.

Hopper

was also wholly committed to representational art and watched the rise of

Abstract Expressionist painting in the 1950s and 60s with dismay. He was a

member of the group of representational painters who, in 1953, launched the

journal Reality as a mouthpiece for their point of view, serving for a time on

its editorial committee. In 1960, he and his Reality colleagues made a

concerted protest to the Whitney Museum and the Museum of Modern Art against

the 'gobbledygook influences' of abstract art in their collections. Curiously

enough, the abstract painters expressed nothing but admiration for Hopper, in

whose work they saw an interest in pure form and a play of space against

flatness that anticipated their own experiments.

In the

words of one friend, Hopper gave off 'a sense of geological presence that

redefined inertia'. He was slow and laconic in his work as a painter,

completing only two or three oils a year, and even more so in his social

manner. He regarded conversation as mere chatter, not worth the physical effort

required to produce it. If he had nothing to say, which was generally the case,

he would remain silent. The idea of filling in awkward moments with small talk

would have seemed as absurd to him as filling in the empty wall-surfaces in his

paintings with pretty decorations.

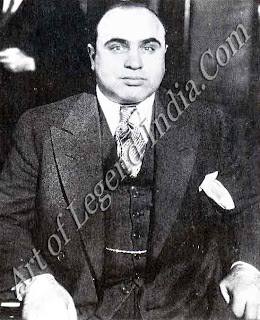

Critics

inferred from the lonely mood that pervades so many of Hopper's paintings that

he must himself have suffered loneliness. He certainly spent much of his time

alone, whether painting, reading or deep in thought, but it was by choice. He

cherished solitude and had little love of company except that of his wife. The

unsmiling suspicious look on his face in photographs makes us feel that we have

intruded into a very private life. It also, somehow, makes us feel small.

lopper's withdrawal from the world was rooted in a profound pessimism; the same

friend wrote that 'he views his fellow man as a flimsy and often trivial

construct'.

The

word that invariably crops up in the recollections of those who knew Hopper is

'puritan'. He did come from an Anglo-Saxon Protestant background: his parents

were of Dutch and English origins, and both devout Baptists. More

significantly, he always conveyed the impression of strong feelings kept

tightly under control, despising any kind of self-indulgent emotionalism or ostentation

as though to give so much away made a person ridiculous.

In

1965, Hopper painted his last picture, Two Comedians, showing a couple

reminiscent of himself and Jo taking their final bow before leaving the stage.

He died in his studio at 3 Washington Square North on 15 May 1967, aged 84. Jo

died the following year and bequeathed the entire artistic estate, including

over 2,000 of Hopper's paintings, watercolours, drawings and prints, to the

Whitney Museum of American Art.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

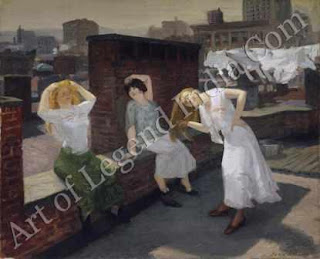

Edward

Hopper at work

Hopper's highly original work gives us an uneasy view of

modern life in America, stressing in particular the loneliness and isolation of

man in the urban environment.

By temperament and by training, Hopper was a realist.

Following in the aesthetic tradition developed by Manet, Degas and the

Impressionists in the nineteenth century, he had no time for idealization,

prettification or fantasy he had no time for beauty, in the conventional sense

of that word. His aim was to recreate the experience of reality intensely

perceived, showing us the kind of people, places and things that we might see

every day, yet somehow imbuing them with that strange and elusive quality we usually,

for want of a preciser term, call 'mood'.

At his best, Hopper was a painter of modernity he delighted

in representing those things that make modern life modern, from petrol stations

to cafeterias. His main province is the public place; private life is only

glimpsed through window, in doorways, at a distance. He presents a detached

view, as if observing modern man for the purposes of some behaviour study. His

brushwork is slow, deliberate and dull, like the most deadpan of commentaries,

and his colour can be almost cruelly harsh, seeming to condemn the garishness

of modern taste.

Hopper disliked being pigeon-holed as a painter of 'the

American scene' there seemed something patronizing about it. Yet the modern

life he depicts is unmistakably and insistently modern life in the USA.

Hopper's great strength was his eye for a good subject, and what better subject

for a painter of modernity than a New World, the discordant grandeur of which

had virtually never been exploited in art?

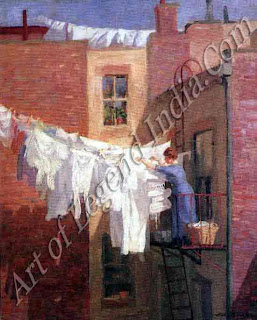

Though Hopper is best known as an oil painter, some of his

most important early work was in watercolour and etching. He first won

recognition as a painter with the daintily executed, sunlight-filled

watercolours he made in Gloucester, Massachusetts in 1923, and he continued to use

the medium with a relaxed, lively touch throughout his life. The

black-and-white technique of etching lent itself more readily than watercolour

to representing the seamy side of the American scene, and Hopper's etchings of

the early 1920s dwell upon landscapes cut across by railway tracks and life in

cheap apartment blocks. It was here that we see his peculiar brand of realism

beginning to emerge.

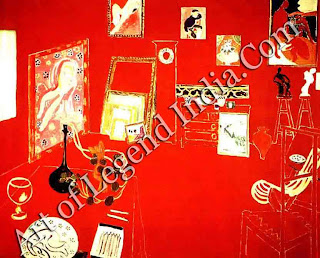

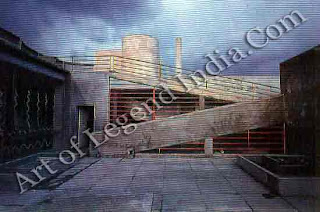

THE INHUMANITY OF THE MANMADE

One of the leading ideas in Hopper's work is the inhumanity

of the manmade. He can suggest the hugeness and bleakness of a big city by

showing just a street corner or the view from a train window. Architectural

forms take on a strange alien presence, mean, hard and repetitive in the city,

aggressively ornate in the suburbs and small towns. Sometimes the environment

is allowed to speak for itself, like a stage-set without actors. Elsewhere

there are people, but they are somehow temporary; they seem not really to

inhabit the place where they happen to be.

The principal legacy of Hopper's Paris days, when he saw and

imitated the work of the Impressionists, was an abiding interest in the play of

light and shade on objects, especially the effects of sunlight on buildings,

inside and out. Hopper orchestrates light as ingeniously as any lighting

manager in the theatre, and the shadows and areas of light take on as much of a

life of their own as the figures and objects over which they play. Indeed, they

perform the crucial function of enlivening and competing with those figures and

objects.

The angles from which Hopper's subjects are viewed may look

casually chosen, even accidental. He will sometimes crop a scene so that a

figure is cut in half; sometimes show the main figure to one side as if by

mistake, allowing most of the composition to be taken up with something

ostensibly rather boring. But these are calculated and essential effects, often

to emphasise a sense of alienation. Photographs might also play a part in the

process, although the image is always quite transformed in the final painting.

Another of Hopper's recurrent themes is transience. His

scenes of travel carry implications that transcend the modern-life context they

stand in an age-old poetic tradition in which the journey is used to suggest

man's journey through life. The roads and railways in Hopper's paintings, the

travellers sitting on trains or waiting for who knows what in hotel rooms and

lobbies, are images of human existence as a transient thing, images of

mortality.

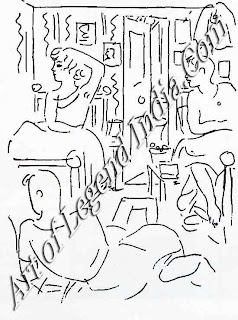

The people in his work often seem-to be in a world of their

own, gazing dreamily into space or intently reading. Sometimes the parts of the

setting around their heads or in front of their eyes will seem to contain their

hovering thoughts, but there is rarely any sense of communication between them.

Instead, they tend to be divided from one another by the furniture or the

architecture into separate compartments of space. They are not brought together

by any definite storyline either. Despite his training as an illustrator,

Hopper deliberately avoids narrative content in his works. Something is going

on but there is no way of telling what, and the situation is all the more

fascinating for its ambiguity.

Hopper was above all a master of expressive space and, in a

way, the spaces between the figures are more important than the figures

themselves. The world he creates in his paintings seems to yawn with emptiness.

Most obviously, he will use empty seats to suggest absence, imparting a lonely

and isolated air to the people who are present. More subtly, his compositions

are contrived to make us look for something that is not there, to give an

uneasy feeling of watching and waiting for someone to arrive, or some event to

occur. To increase our unease, he will slightly distort perspective, just

enough for us to sense that something is wrong without being able to say

exactly what it is. He was a realist, but with an angle, and his aims and

methods were hardly as straightforward as that term might imply.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

The Ashcan Sch00l

Labelled

as vulgar by the critics, the Ashcan school of painters was a flourishing and

original group whose inspiration was drawn from New York street scenes and the

seamier side of city life.

In the

early years of the 20th century, American painting finally emerged from the

shadow of European art and began to assert its own identity. Leading these

advances was a group of social realist painters who came to be known as the

Ashcan school.

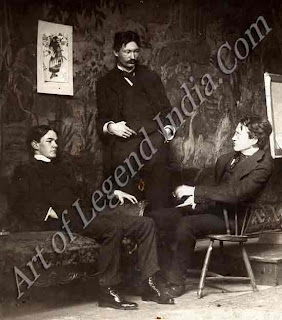

The leader

of this influential group was the painter and teacher Robert Henri. Born Robert

Henry Cozad, Henri changed his name after his family was forced to flee

Cincinnati following his father's involvement in a shooting incident. Henri's

own work came firmly within the European orbit, his portraits bearing a close

resemblance to those of Manet. However, Henri's true importance lay in the

direction that his teaching gave to the realist movement. One commentator

described him as a 'silver-tongued Pied Piper'.

Henri

travelled to Europe on several occasions in the 1880s and 1890s. In 1888, he

was in Paris, studying under the academic painter, Adolphe Bouguereau and, in

1895, he visited Holland with William Glackens. Like Henri, Glackens' link with

the Ashcan school was tempered by his obvious fondness for European art and his

canvases reveal a particular liking for the work of Renoir.

On his

return to the States, Henri settled in Philadelphia and, from 1892-95, he

taught at the Women's School of Design. His own studio became a popular meeting

place for artists and it was during this period that the future members of the

Ashcan school first came together. Many of these artists worked initially as

illustrators on newspapers. George Luks, Everett Shinn, John Sloan and William

Glackens all began their careers this way, before Henri persuaded them to take

up painting and translate the immediacy and topicality of their journalistic

work into a vigorous new form of

American art.

Henri

preached a positive brand of liberal humanism, stressing his belief in

progress, justice and the common bonds of humanity. He called upon artists to

portray modern American life, not with the superficial prettiness that was

popular in the academies, but with the social awareness of a Goya or a Daumier.

'Be willing to paint a picture that does not look like a picture,' was his

maxim.

ACADEMIC REJECTION

Towards

the end of the 19th century, the Philadelphia realist painters migrated to New

York, where the overcrowded suburbs gave an increasingly urban slant to their

pictures. Cinema audiences and street scenes in the slums were typical

subjects, while bars like McSorleys provided a virtual replica of night life in

the Latin Quarter of Paris.

In New

York, however, they also came up against the opposition of the National Academy

of Design. This imposing body had been founded in 1826 and was, in its early

days, an important sponsor of native American art. By the time that

Impressionism and Realism made their appearance, however, it had become

extremely conservative. In 1907, Luks, Glackens and Shinn were among the

artists who had their works rejected for its annual show. Henri, who was one of

the selection committee on this occasion, withdrew his own entries in protest

and set about organizing an independent exhibition.

The

result was a show by 'the Eight', which took place in February 1908 at the

Macbeth Galleries, where Henri had previously held a one-man exhibition. 'The

Eight' were not a cohesive group and this was to be the only time they

exhibited together. Nonetheless, the vitality and modernity of the paintings on

display made this a landmark of American art and a rallying point for

supporters of the avant-garde. The critics, however, were 'less enthusiastic.

'Vulgarity smites one in the face at this exhibition,' complained one

correspondent, and the feeling that certain artists were glorying in the noise

and the squalor of city E life earned them the tag of 'the Ashcan school'.

Only

five of 'the Eight' were attached to the Ashcan group Henri, Luks, Shinn, Sloan

and Glackens. Of these, probably the artist who best typified its spirit was

John Sloan, who is sometimes known as 'the American Hogarth'. Sloan was a

committed socialist and was later a co-founder of The Masses, a political

journal to which Henri, Luks and Bellows all contributed E illustrations. His

diaries show how closely he based his paintings on the scenes and incidents

that he witnessed in the city streets. Hopper was a fervent admirer of his work

and in an article of 1927, entitled 'John Sloan and the Philadelphians', he

singled out the former's Night Windows for particular praise. Then, a year

later, he produced his own version, using the same voyeuristic theme of a woman

glimpsed through an open window.

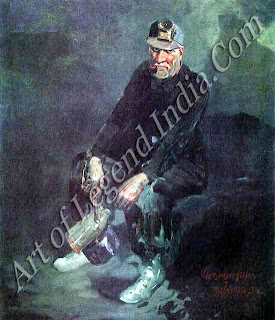

Where

Sloan viewed the life of the poor with sympathy and as a forum for political

struggle, George Luks found the slums a source of vigour, excitement and

modernity. Luks, himself, was a flamboyant and brash character and sought to

project this image in a series of extravagant fabrications about his early

career. His claims to have earned a living as a coal miner and as a fighter

called 'Chicago Whitey' and 'the Harlem Spider' are probably apocryphal, but it

is true that he was almost killed by a firing squad when, as a reporter, he was

sent to cover the Spanish-American war in Cuba. Luks' painting shows a similar

sense of adventure, with a loose handling and brushwork that reveals a clear

debt to Frans Hals. His style is best exemplified by his depiction of

wrestlers.

RED-BLOODED ART

Fighting

scenes were also popular with George Bellows, another painter associated with

the Ashcan school. Bellows did not exhibit with 'the Eight', but his art

contained many of the aggressively American qualities that typified the spirit

of the group. He never went abroad and thus found it easier than his colleagues

to ward off European influences. In addition, he was a keen sportsman and

seemed to symbolize the Ashcan ideal of the all-American, red-blooded male.

In his

youth, he played semi-pro baseball at Columbus, Ohio, and was invited to join the

Cincinnati Reds. Bellows chose art as a career instead, although his continuing

interest in sport is evident from his paintings. He depicted baseball, polo and

tennis scenes, but is most famous for six stirring pictures of boxing matches.

Prize-fighting

was illegal in New York at this time, and bouts were staged in private athletic

clubs, with both the spectators and the fighters taking out temporary

membership. Bellows' studio was almost opposite Sharkey's Club in Broadway, and

this venue provided a rich source of material for him. His brutal ringside

views are remarkable both for the blurred, mask-like faces of the audience and

for their sheer presence which, in the absence of photographic reporting, must

have seemed all the more striking. Bellows emphasised his interest in the

physicality of such scenes. 'Who cares what a prize-fighter looks like?' he

commented, 'its muscles that count.

Bellows

had considerable conventional success, becoming the youngest Associate of the

National Academy in 1909. For his colleagues, however, it was more important to

set an alternative standard to these academic plaudits. In 1910, Henri

organized the Exhibition of Independent Artists; it was the first American show

to have no jury and no prizes, and where each painter paid for the space he

used.

Three

years later, modern art made its decisive breakthrough in America at the Armory

Show. Ironically, the impact of the European contributions at this exhibition

made the work of the urban realists seem old-fashioned and heralded their

decline. It required the emergence of Hopper, Henri's pupil, to underline the

true achievements of the Ashcan school.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

A Year in the Life 1929

Hopper

had already forged his distinctive style so evocative of urban desolation when

the Wall Street Crash of 1929 shattered the American Boom and international

hopes for peace and prosperity. A world depression and the 'Hungry Thirties'

were just around the corner.

For

most of 1929, the Western world was not only prosperous but peaceful. One

government after another committed its people to the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact

which renounced war as an instrument of policy. The USSR and USA, though

non-members of the League of Nations, adhered to the Pact, which eventually had

65 signatories. In 1929, the Young Plan tackled the remaining cause of

ill-feeling between Germany and the wartime Allies by slashing the burden of

reparations, and Allied troops began evacuating the Rhineland, which had been

occupied since the end of the War. The French statesman Aristide Briand put

forward proposals for a federated Europe.

A spate

of books appeared which were more or less openly anti-war, concentrating on its

horrors rather than questions of national 'war guilt'. Three famous examples,

published in 1929, were Robert Graves's autobiography Goodbye To All That,

Ernest Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms, and the German writer Erich Maria

Remarque's international best-seller later a famous film All Quiet on the

Western Front.

THE WALL STREET CRASH

The

economic situation in the West was somewhat shaken except in the United States,

where real wages and national wealth had doubled since the War. Prices of

shares soared on the Wall Street Stock Exchange, till it seemed that, if you

bought, you were certain to make money. Speculative mania raised the Dow Jones

index to 300 by the end of 1928, and the trend continued through 1929. The

index peaked at 381 in

August

1929; then, in September, confidence faltered and on 'Black Thursday', 24

October, the Crash came, with wave after wave of panic selling. By November,

Dow Jones was down to 197 and thousands of speculators had been ruined.

Frightened people rushed to secure their remaining capital, causing a

disastrous run on the banks followed by closures that created new panics. In a

downward spiral, industries were disrupted and millions became unemployed. The

Great Depression lasted for years and, since the USA was a great creditor nation

(and was soon to start calling in its loans), it spread all over the

industrialized world. Apart from shattering the European economies, the

Depression wrecked the Young Plan, destroyed many people's faith in democracy,

and made possible the rise of Hitler and other dictators.

This

year also marked the beginning of a new era for Soviet Russia, where Joseph

Stalin had emerged as the leading figure. Stalin's principal rival, Trotsky,

went into exile, and his theory of fomenting world-wide 'permanent revolution'

was abandoned in favour of Stalin's policy of building 'socialism in one

country'. At the same time Stalin defeated the 'Right Opposition', which

opposed as premature the policy of collectivizing agriculture. The Rightist

leader, Bukharin, and his closest associates were expelled from the Politburo.

Other

events of 1929 included Alexander, King of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes,

declaring himself dictator, and re-naming his kingdom Yugoslavia. As a result

of the Lateran Treaties between the Papacy and Mussolini's Italy, the Pope

ceased to be the 'prisoner of the Vatican' (self-immured since the new Italian

state seized the city of Rome in 1870). The Vatican was recognized as an

independent city-state and Catholicism became in effect the state religion.

Other

events of 1929 included Alexander, King of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes,

declaring himself dictator, and re-naming his kingdom Yugoslavia. As a result

of the Lateran Treaties between the Papacy and Mussolini's Italy, the Pope

ceased to be the 'prisoner of the Vatican' (self-immured since the new Italian

state seized the city of Rome in 1870). The Vatican was recognized as an

independent city-state and Catholicism became in effect the state religion.

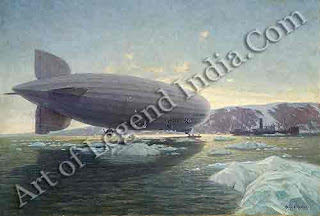

In

1929, the 'Talkies' were all the rage, and cinemas everywhere were being

re-wired for sound. Sunbathing had become popular, and the first precautionary

aids sun-tan lotion and Mexican straw hats appeared. The German Graf Zeppelin

airship flew around the world while Richard Byrd, the American pioneer aviator,

flew over the South Pole. The Museum of Modern Art in New York was opened. The

ballet impresario Serge Diaghilev died, as did the two giants of First World

War France, Marshal Foch and George Clemenceau. More ominously, so did the

architect of Franco-German reconciliation, Gustav Stresemann.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish