Showing posts with label Life of Van Eyck. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Life of Van Eyck. Show all posts

The

works of Jan van Eyck are celebrated for their visual splendour and precision

of detail. Their brilliant colours and magnificent definition are due to Jan's

refinement of the oil-painting technique.

Jan van

Eyck was highly praised in his own time, and is traditionally renowned as the

founder of the Netherlandish school of painting. His fame rests largely on the

illusion of reality he created in his paintings and his delight in naturalistic

detail and rich, decorative effects.

Little

is known of Van Eyck's early career, and the paintings which survive are those

of a mature artist, well-practiced in his craft. Most of Van Eyck's work for

Philip of Burgundy was of a decorative and temporary nature, and has long since

disappeared. His surviving works were painted for rich and aristocratic

patrons, men moving in court circles. For them Van Eyck created majestic

Madonnas, rather than the more homely women of his contemporary, Robert Campin,

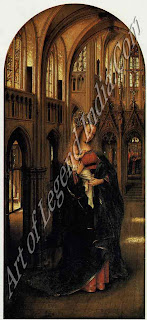

who worked for bourgeois patrons. Even when placing the Virgin and Child in a

domestic setting, then popular, Van Eyck elevated his Madonna on a throne-like

chair, with a brocaded canopy overhead and rich carpet underfoot. Elsewhere in

The Ghent Altarpiece and The Madonna with Canon van der Paele he depicted the

material splendour of bejewelled robes and crowns to speak of the richness of

heaven.

This

was a period of growing demand for life-like portraits, and a time when faith

was direct and called for clear and 'real' images of religious doctrine. Van

Eyck responded by exploiting his acute powers of observation and his formidable

technique to produce unique illusions of reality. Whilst Van Eyck observed the

world around him, he never attempted to reproduce it with topographical

accuracy. Instead, he used his knowledge to create imaginative landscapes,

townscapes and interiors that would appear familiar to his patrons. The

background to The Madonna with Chancellor Rolin has the feel of the River

Meuse, but the town cannot be identified.

By the

1430s, Van Eyck broke with tradition and refined a new plateau-type

composition, where the foreground figures appear to be higher in the imagined

space than those in the background. This enabled him to develop his interest in

landscapes with far-reaching vistas. He also began to explore the relationship

between interior and exterior, looking through a window or over a parapet, and

was perhaps the first painter to present the back view of figures gazing into

the landscape, in The Madonna with Chancellor Rolin.

The

exact, scientific perspective developed in Florence was unknown in Flanders,

but Van Eyck explored an empirical method of perspective to paint his

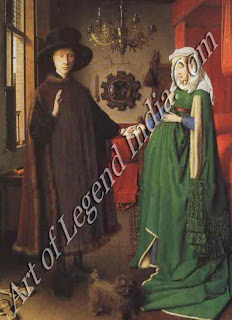

interiors. By the time of the compelling Arnolfini Wedding, he was perfectly

able to create the novel effect of a real space opening forward, which seemed

to continue beyond the frame and include the viewer.

Symbolism

is an important element in Van Eyck's religious and secular works. In The

Arnolfini Wedding he was concerned to include numerous symbols of faith,

without disrupting the overall natural effect. The symbols appear at first

sight to be everyday objects, but Van Eyck probably chose them for their

traditional symbolism: a lighted candle in a chandelier indicating the presence

of God, a griffon terrier, fidelity, a carafe of water, the purity of the

Virgin, and a beam of light through a window, the Incarnation.

Vasari

and other early biographers credited Van Eyck with the invention of oil

painting. In fact it had been known for many years but was used in a limited

way. However, in Van Eyck's time, improved varnishes, diluents and driers were

distilled, and Jan explored the possibilities of their use with an

unprecedented sophistication. He painted on the usual wooden panel covered with

a smooth layer of gesso (plaster), then, and after beginning his work with

opaque paint, he would apply many thin layers of translucent, oil-based colour

glazes to achieve the glowing and luminous effects characteristic of his work.

It was

Van Eyck's technical expertise that enabled him to reproduce the visual world

convincingly. His figures are enhanced by natural lighting and on occasion he

even created the illusion of a foot or angel's wing projecting forward out of

the picture. He also delighted in the precise rendering of texture.

Van

Eyck's contribution to portraiture was also significant. He abandoned the

Gothic tradition of exaggerated physical features in favour of a life-like

description of the individual face. He realized that the three-quarter view,

with head turned halfway between profile and full-face, could be much more

naturalistic than the conventional profile. He understood that if the face was

turned towards the light, he could use the shadow playing over the visible side

to describe minute details of the surface. With his usual ingenuity, he

explored ways to include the hands to greatest effect, and experimented with

the impact of a novel device a direct glance out of the picture.

Van

Eyck also appears to have given considerable thought to the inclusion of

appropriate inscriptions in many of his works. These were often incorporated

into the painting itself, or worked into the picture frame. The motto 'As Best

I Can' appears several times, reflecting a pride in his work and a becoming

humility.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

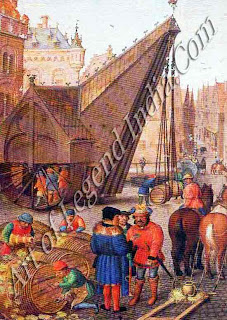

The Port of Bruges

Now a

town of quiet tree-lined canals and fine medieval architecture, Bruges once led

a very different life it was the trading centre of the whole of north-west

Europe.

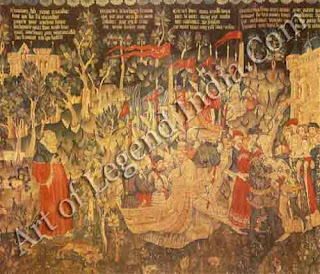

On a

January day in 1430, the Flemish city of Bruges was on its best behaviour.

Thousands of its citizens lined the narrow streets, jostling and straining to

catch a glimpse of the Princess Isabella of Portugal as she passed by. She had

arrived from her homeland to be with her future husband, Duke Philip the Good

of Burgundy.

Among

the Duke's enormous entourage that day was no less than 40 varlets de chamber.

One of them was Jan van Eyck. For the last part of his life, Van Eyck was based

in Bruges, a port on the Zwijn River, almost 10 miles inland from the North Sea.

His works helped to characterize the city as the cradle of Flemish painting.

But Bruges had already won an enviable reputation as a major centre of the

medieval cloth industry, and as the main international emporium of north-west

Europe.

As one

French chronicler noted, when describing that royal entry of 1430, Bruges was

'thronged with visitors from foreign lands . . . a centre for merchandise and a

meeting-place for those of other lands, where pass greater quantities of goods

than, perchance, in any other city of Europe'. The chronicler added, 'and a

great shame it would be if ever Bruges were destroyed. .

In

subsequent centuries Bruges declined, but it never was destroyed. Thus the city

of Van Eyck's era has not completely disappeared from view. Many of the homes

of the medieval bourgeoisie are still standing tall, thin houses, mostly built

of brick, subtly decorated with pink or grey sandstone, white stone from

Brabant or blue Tournai limestone. Their large rooms are lit by spacious

windows, which once allowed the householder's prized oil paintings to be seen

to their best advantage. The old Market Hall can still be identified from afar

by its distinctive belfry. The Town Hall, the Church of Notre Dame and the

Beguinage a retreat for secular nuns all survives to recall the city's former

prosperity.

EARLY TURMOIL

Yet

this tangible legacy can easily mislead. The quiet canals and the dignified

Gothic architecture create an atmosphere of tranquillity, even of serenity. But

this belies the turmoil of the city's early history, when its citizens fiercely

resisted the efforts of Flemish counts and French kings to subdue them; in

their halcyon days the Three Members from Flanders' Bruges, Ghent and Ypres

virtually governed the province between them. Bruges was no quaint medieval

backwater. It was a tumultuous commercial city, where merchants from 17 nations

operated, and 20 states were represented by official ministers.

In

medieval times, the continent comprised two main commercial zones that of the

Baltic and the North Sea, and that of the Mediterranean. Bruges began to

prosper as a textile centre within the northern zone, and also as a convenient

port for the commercial traffic between England and Flanders. As the Flemish

cloth industry came to rely more and more heavily on English supplies of wool,

so the trade of Bruges expanded rapidly.

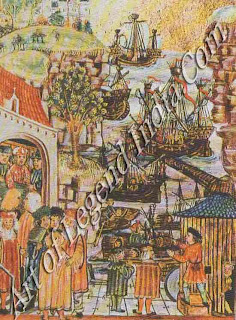

TRADE GROWS

The

port then evolved into something far more than a simple Anglo-Flemish trade

junction. Germans, Normans, Bretons and Spaniards came in increasing numbers to

buy and sell at Bruges's annual fair, established in 1200. Before the end of

the 13th century, the great galleys of Genoa and Venice were heading regularly

for the northern port. So at a time when land communications were unreliable,

Bruges became the destination of seaborne merchants from both the northern and

southern commercial centres of Europe.

The

native Flemings did not themselves develop as international merchants. Instead,

the foreign community of Bruges grew larger and it became a truly cosmopolitan

city. Its prosperity came to rely not on intermittent fairs, but on permanent

trade. Merchandise was sent there for distribution in all directions and the

commodities which found their way on to the quayside came from around the

world. There were Russian furs, northern cloths, wines from Burgundy, Bordeaux

and the Rhine, and metals from Germany. There was wool, tin and cheeses from

England, butter and pigs from Denmark, corn from Prussia, and salt fish and

dried fish from Norway. And there was Baltic timber in abundance, and fruit

from Spain. Perhaps the most exotic goods were those stocked in the warehouses

of the spice-importers, cinnamon from Ceylon, cloves from the Molucca Islands,

mace from Arabia not forgetting the saffron, cinnabar, ivory and oil of white

poppy which were used as artists' materials.

FINANCE THRIVES

Such a

thriving commercial centre naturally attracted businessmen. By 1369 there were

15 separate 'merchant banks' there. Italian bankers and money-lenders were keen

to establish their northern branches in the city. In 1469, the Medici of

Florence had a staff of eight at Bruges, one of whom was responsible for

purchases of cloth and wool, while another had the duty of selling silks and

velvets to the Burgundian court. Giovanni Arnolfini, whose wedding portrait was

painted by Van Eyck, was himself an Italian expatriate from Lucca. He was one

of the leading importers of alum, a substance essential for the dyeing of wool.

Germans

as well as Italians found the city to be a profitable home-from-home. Bruges

was one of the Hanseatic League's overseas trading posts, along with London,

Bergen and Novgorod. The League had been formed by German merchants to give

political backing to their trading agreements. The trading posts, or kontore,

were independent from their host country. Within them, members were under the

jurisdiction of German law; houses, offices and warehouses were all corporately

owned and here the League members lived and traded.

Communities

of foreign merchants at this time, were often encouraged to live in a

particular area of a city, separate from the native citizens. In Bruges,

however, the Hanseatic League were not confined to specific quarters of the

city but lived among the Flemings. Elsewhere in northern Europe, these

privileged German League communities often encountered native resentment, but

their kontore was welcomed in Bruges and seen as a source of extra trade and

revenue, increasing the city's prosperity.

A large

proportion of the citizens, however, did not share in the general affluence.

They had to endure the rigours and squalor of medieval urban life as best they

could. 'This is no place for poor people', wrote Tafur of Seville, a

scandalized visitor, in 1435. He also commented with disapproval on the

bourgeoisie, with their 'baths for men and women in common, a practice which

they look on as normal and decent as we do going to Mass. There is no doubt he

went on, 'that there is considerable licence . . .' He probably noticed local

zeal for alcohol too in 1420 the annual consumption of wine per head of the

population was 100 litres.

There

were certainly plenty of opportunities to over-indulge on occasions such as the

24 great tournaments held at Bruges between 1405 and 1482 for example. Those

well-heeled burghers, who liked to have themselves depicted in attitudes of

pious austerity, also revelled in their conspicuous consumption. Bruges in the

mid 15th century was, however, a city that had already started to decline. The

river Zwijn began to silt up during the 14th century. By 1490 it was completely

blocked and Bruges then ceased to be an important port commercially, although

it flourished artistically under the Dukes of Burgundy.

By

1500, Antwerp had taken over the commercial mantle and some people began to

talk of 'Bruges le mort' (Bruges the dead). But it could almost be said that

its great painters at this time had already conferred a kind of immortality on

the city.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

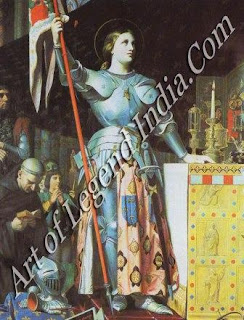

1429

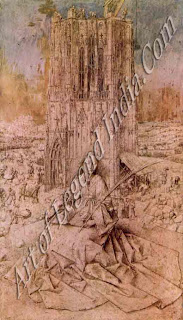

While

Van Eyck was fulfilling a delicate commission to paint a likeness of the

Portuguese princess Isabella, so that Philip of Burgundy could decide whether

or not to marry her, a young French girl was embarking on a military career

which would tip the balance of power between France and England.

As the New

Year, 1429, dawned, France was in a turmoil. The French crown was claimed for

the English boy king, Henry VI; and the claim seemed likely to be made good.

Leaving their Burgundian allies to guard the north-east, the English were

pressing south and had besieged the important town of Orleans. The French had

become demoralized by a string of English victories, and the dauphin, Charles

(last Charles VII), was still uncrowned; his legitimacy was in doubt and he was

only recognized as king south of the Loire. But the next few months were to see

one of the most remarkable phenomena of the late Middle Ages, the brief but

spectacular career of Joan of Arc, whose convictions changed history.

In

January, 1429, Joan was 17 years old, a simple farmer's daughter from the

village of Domremy in Lorraine. But from the age of 13 she had seen visions and

heard voices she identified as the Archangel Michael and Saints Catherine and

Margaret. Her voices told her that it was her mission to lead France to victory

and see Charles crowned at Reims.

HEROINE DRESSED AS A BOY

The

previous summer, in 1428, she had tried to persuade the local French captain at

Vaucouleurs, 12 miles away, to help her in her mission. The captain did little,

and when the news of the siege of Orleans came through, she dressed in men's

clothes, had her hair cut short and, in January, 1429, set off to find the

dauphin herself. Early in March, she presented herself at the Chateau of

Chinon, where she proved immediately that she was either heaven-sent or

extremely intelligent. For Charles had told one of his courtiers to take his

place on the throne before Joan entered the room, but she had no trouble in

picking out the true king at first sight which may or may not have had

something to do with his notoriously unprepossessing appearance. At any rate,

Charles was won over, and after a thorough investigation into her religious

credentials, Joan was given a suit of white armour, a black charger and her own

banner and pennon, and sent to Tours to join the army. Joan is said to have

supplied her own sword, miraculously indicating the spot where one lay buried

behind an altar.

Whether

inspired or simply fanatical, Joan had immense charisma and even greater courage.

Where she led, the soldiers of France would follow. She was absolutely

convinced that God was on the side of France. The three letters she dictated

and sent to her enemies reflect her confidence 'You Englishmen, who have no

right in the kingdom of France the King of Heaven commands you by me, Joan the

Maid, to leave your strong-holds and return to your own country!'. By May, the

French had driven the English besiegers from Orleans and, as the French overran

the English bastilles, it was Joan who planted the first scaling ladder. A

series of brilliant victories followed. With the enemy badly shaken, Joan

spurred on the dilatory Charles to enter Reims, and in July he was finally

crowned in the Cathedral with 'the Maid of Orleans' standing by his side.

By the

end of the year, Joan's run of success began to falter and in the autumn she

was wounded in the thigh with an arrow though her fellow soldiers had to drag

her by force from the battlefield. But she remained an enormous inspiration to

the French and when the English captured her the following year they tried

desperately to have her discredited with a show trial, before allowing her to

be burned at the stake as a dangerous and influential heretic.

ENGLAND'S LOSSES

The

English dislike of Joan was understandable. At the beginning of 1429, they were

poised to overrun all France. By December, they had been pushed back into the

region round Paris and the alliance with Burgundy was less sound than it had

been before the maid intervened.

Writer

– Marshall Cavendish

All of Jan van Eyck’s

dated paintings are from the last decade of his life, when he was complete

master of the new oil-painting technique. Subsequent painters have developed

other aspects of the rich potential of oil, but no-one has ever surpassed Jan's

skill in the minute rendition of texture or the creation of glowing effects of

colour. The Ghent Altarpiece, with its countless figures, its beautiful

landscape and townscape backgrounds, and its exquisite still-life details, is

like I a manifesto of the possibilities of oil paint.

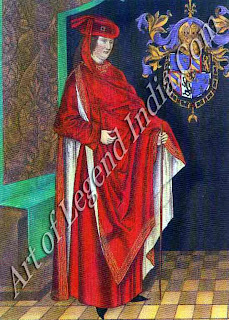

Van Eyck’s other

paintings are either religious paintings or’ portraits. Sometimes he combined

the two, as in The Madonna with Chancellor Rolin and The Madonna with Canon van

der Paele, and his most famous portrait The Amolfini Wedding has religious P

overtones in its symbolic references to the sanctity of marriage. His

individual portraits, such as Cardinal Albergati and Baudouin de Lannoy, show

his matchless ability to combine unrelenting physical scrutiny with a feeling

for the sitter’ s inner life.

This portrait has an inscription in Greek

characters reading Timotheos’, the name of a famous musician of antiquity. This

has led to speculation that the sitter was a musician, perhaps Gilles Binchois, one of

the leading Flemish composers of the period and like Jan van Eyck a member of Philip the Good’s court.

Giovanni Amolfini was a merchant from Lucca in Italy who settled in Bruges in 1420. His wife, Giovanna Cenami, was also from Lucca. This painting was almost certainly commissioned as a document of their wedding; varioussymbolic details (such as the dog, representing fidelity) attest to this, and it has an appropriate solemn dignity.

Nicolas Rolin, who is shown praying in front of

the Virgin and Child, was Chancellor of Burgundy and Brabant. The three arches

are probably intended to symbolize the Trinity (Father, Son and Holy Ghost); through them is seen a breathtaking landscape that shows Van Eyck's mastery of space and atmosphere.

These two panels, painted in grisaille (shades

of grey) may originally have been the outer wings of an altarpiece, but it is

possible that they always formed a diptych (a pair of pictures hinged down the middle). They are

remarkable pieces of illusionistic skill; the figures, which are like miniature

statues, appear to stand in front of the frames (painted, not real) and they cast delicately observed reflections on the polished background.

This painting is also known as the Lucca

Madonna, as it was once owned by the Duke of Lucca. It is one of Van Eyck‘s

most tender and intimate works, but it also has great dignity. As with so many of Van Eyck’s

paintings, the beautifully observed details can often be symbolically

interpreted; the four lions on the Virgin's splendid canopied throne, for example, make reference to those on

the throne of Solomon, wlzere they symbolized royal power.

Writer - Marshall Cavendish