Piero Della Francesca Artist life

Piero della Francesca is now perhaps the most revered

Italian painter of his period, but his great celebrity is fairly recent. In his

own day he was well known as a mathematician and theorist as well as a painter,

but by the 17th century he was almost forgotten, and it is only in the 20th

century that his severe purity of form and s consummate mastery of light and

colour have become fully appreciated.

The tardiness of Pieros elevation to the pantheon of great

artists reflects the restive obscurity of his career. Most of his life was

spent in the small town of Borgo san Sepolcro, and although commissions took

him to nearby 2: city-states, his work never had the exposure of that of ' many

of his great contemporaries. Now, however, his fresco cycle at Arezzo is

properly recognized as one of Italy’s greatest art treasures.

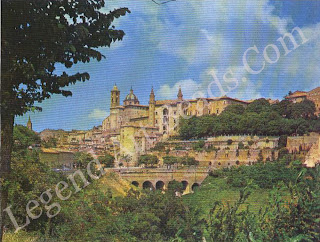

Sansepolcro's Famous

Son

Piero spent most of

his life in Sansepolcro, the little Tuscan town where he was born; but

prestigious commissions took him further afield, to some of the most illustrious

Renaissance courts.

Piero della Francesca was born between 1410 and 1420 in the

small town of Borgo san Sepolcro (nowadays known as Sansepolcro), some 40 miles

south-east of Florence. His father Benedetto, a tanner and boot maker, is said

to have died before the boy was born, and Giorgio Vasari's 16th-century life of

Piero tells us that he was brought up by his mother, Romana. She came from

nearby Monterchi, where the tiny chapel of the cemetery is decorated with

Piero's fresco of the Madonna del Parto (Virgin of Childbirth,). The picture's

subject makes it a fitting homage to the artist's mother, who may well have

been buried at her birthplace.

LITTLE DOCUMENTATION

We have no record of Piero's early years, and few documents

from any period of his life. In 1442, and again in 1467, he was elected a town councilor

at Sansepolcro, and over the years he carried out several commissions for

paintings there. It was at Sansepolcro that he made his will, and he died

there, the town celebrity, in 1492. Piero clearly loved his birthplace,

returning there all through his life. Features of the town and its surrounding

countryside appear in a number of 1250

His paintings. But the search for wider artistic experience,

and the quest for commissions, took him further afield, to the Papal court at

Rome and to the towns and city-states of Florence, Ferrara, Rimini and Urbino.

It is in Florence that we first hear of him, working with the painter Domenico

Veneziano on the fresco decoration of the church of Sant'Egidio (now

destroyed). The record, dated 7 September 1439, does not make it clear whether

or not Piero was still learning his trade as Domenico's assistant.

A young man of

Piero's gifts would in any case have found plenty to instruct and excite him in

Florence. Having defeated its great rival, Pisa, the city was at the zenith of

its power. In the midst of its vivid artistic and intellectual life, Piero

absorbed the influence of such painters as Gentile da Fabriano, who worked in

the florid International Gothic style, and Masolino and Masaccio, whose

frescoes must have impressed Piero with their grave monumentality.

The artist would also have heard excited discussions on the

new theories of perspective, set forth in Leon Battista Alberti's treatise on

painting, Della Pittura. Piero went on to become a renowned master of

perspective to the architect Bramante and writing a work of his own entitled De

prospection pingendi (on perspective in paintings)

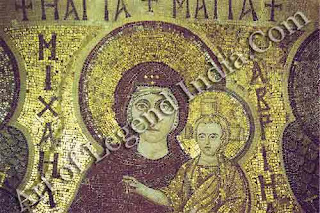

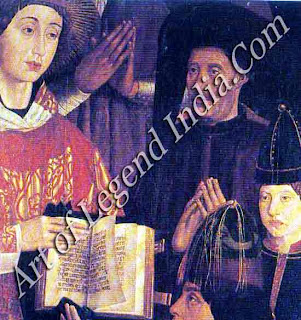

A BYZANTINE DIGNITARY

One public event that took place during his stay in Florence

seems to have made a strong impression on Piero. In 1439, John Paleologus, the

Byzantine Emperor, arrived in the city from Constantinople. He had travelled to

Italy with the dignitaries of the Eastern Church in search of Christian unity against

the Turks. At the Council of Florence, agreement between the two Churches was

solemnly proclaimed. It was to prove short-lived, and the capture of

Constantinople by the Turks in 1453 cast a shadow over the mid-century and led

to calls for a new Crusade. This theme is later invoked in Piero's Flagellation

where the bound figure of Christ can be seen as a symbol of the Eastern

Christians who were suffering at Turkish hands.

In 1439, of course,

all this lay in the future. Both the spectacle of the Emperor and his retinue,

with their sumptuous and exotic garments, deeply impressed the Florentines. The

splendour of Piero's Solomon Receiving the Queen of Sheba part of his great

fresco-cycle at Arezzo shows that the memory was still fresh 15 years after the

event.

From Florence, Piero

returned to his native town, where in 1445 he was given his first recorded

commission, for the polyptych known as the Misericordia Altarpiece Only partly

by Piero's own hand, this seems to have taken an inordinate time to complete;

the final payment for it may have been made as late as 1462. A slow and

meticulous worker, Piero was also often called away to work for other patrons.

Some time before

1450, he visited Ferrara. Although no trace of his work remains, his influence

on later Ferrarese art is unmistakable. The court of the d'Este family at

Ferrara was de-voted to the crafts of war and hunting, the love of pleasure,

the intrigue of dynastic politics, and the pursuit of learning and the arts.

Here, Piero would have seen the works of the great Netherlandish painter,

Rogier van der Weyden, who had probably stayed at the d'Este court the previous

year.

THE TEMPLE OF

MALATESTA

Piero was next called to Rimini, where the notorious

Sigismondo Malatesta obtained his help in the ambitious redecoration of the

Church of San Francesco, known as the Tempio Malatestiano (Temple of

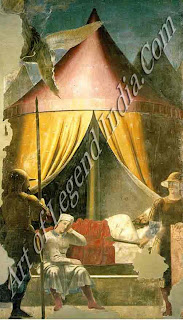

Malatesta). Piero's contribution, a

Fresco showing Malatesta kneeling in veneration of his

patron saint, Sigismund, is notable in being his only dated work - inscribed

1451.

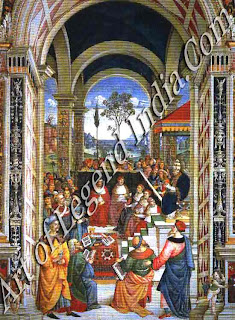

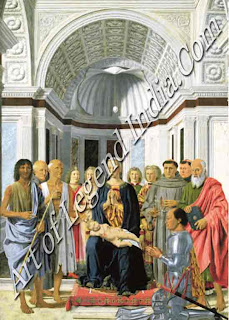

Piero also worked for Malatesta great rival

Federigo da Montefeltro, whose model court at Urbino was a famous centre of

humanist learning and the arts. Piero travelled there many times between 1450

and 1480, and his Urbino pictures include two of his best-known works, The

Flagellation of Christ and the striking diptych (now in the Uffizi, Florence),

which shows Federigo and his wife, Battista Sforza, in profile against a

luminous landscape of lightly wooded hills and pale tranquil water In the early

1450s Piero began work on his largest commission, the Arezzo frescoes.

The

Bacci family, wealthy merchants of the town, had entrusted the decoration of

their chapel in the church of San Francesco to Bicci di Lorenzo, a Florentine

painter of the old school. When Bicci died in 1452, before he had begun work on

the walls, Piero was called in, and together with his assistants spent most of

the next 12 years on the task. In 1459 he visited the Papal court at Rome to

decorate the chamber of Pius I (his work, writes By 1466 the Arezzo cycle was complete. Although many

important paintings still lay before him, Piero was never to work on so large a

scale again. Some critics have suspected a loss of enthusiasm in these later

years, but such a picture as the National Gallery Nativity -

unquestionably a late work - hardly shows lack of inspiration.

BLIND IN OLD AGE

Tradition holds that Piero lost his sight in old age. A lantern-maker

of Borgo san Sepolcro, Marco di Longaro, told a 16th-century memoirist that as

a boy he used to 'lead about by the hand Master Piero Della Francesca,

excellent painter, who was blind'. Be that as it may, Piero was able to declare

himself 'sound in mind, in intellect and in body' as late as 1487, when he

wrote his will in his own hand. Unmarried and without children, he left his

property to his brothers and their heirs. Five years later, he died, and was

buried in the family grave in the Abbey of Sansepolcro. The record of his death

can be seen in the Palazzo, now the town museum and art gallery, where his

superb painting of the Resurrection still hangs today: 'M. Pietro di

Benedetto de 'Franceschi, famous painter, on 12 October 1492.'

Writer-Marshall Cavendish

THE

PIERO DELLA FRANCESCA AT WORK

THE

PIERO DELLA FRANCESCA AT WORK Another

aspect of that vision, and the one which perhaps gives us the most immediate

and intense pleasure, is the harmony of Piero's colours. Despite the damage

they have suffered, the Arezzo frescoes never fail to strike visitors with

their luminous freshness. This quality is seen at its best in Constantine's

Victory over Maxentius where Piero's restricted palette achieves a richly

symphonic effect. The same harmony unites the colours of the garments in

Flagellation, and brings together the two angels in the Madonna del Parto,

whose attitudes and clothing echo one another in a heraldic mirror-image.

Another

aspect of that vision, and the one which perhaps gives us the most immediate

and intense pleasure, is the harmony of Piero's colours. Despite the damage

they have suffered, the Arezzo frescoes never fail to strike visitors with

their luminous freshness. This quality is seen at its best in Constantine's

Victory over Maxentius where Piero's restricted palette achieves a richly

symphonic effect. The same harmony unites the colours of the garments in

Flagellation, and brings together the two angels in the Madonna del Parto,

whose attitudes and clothing echo one another in a heraldic mirror-image.