The Hindu Triad

As

we have seen, the idea of a triad of gods is rooted in the earliest Indian

beliefs and seems to have its origin in solar cults, for the 'three-bodied' sun

created with his fertilizing warmth, preserved with his light, and destroyed

with his burning rays. Though the triad remained, its members changed, so that

the Adityas (Varuna, Mitra and Aryaman) gave way to Agni, Vayu and Surya, and

Vayu in turn gave way to lndra. These deities were sometimes thought of simply

as the three most important gods, some-times as components of a single god

embracing the world: Agni is the earth god, Vayu or Indra is the god of the

atmosphere and Surya is the god of the sky. In the Rig Veda, Indra is closely

united not only with Agni but also with Vishnu (in his earl form). But in the

Brahmanic and especially in the Upanishadic period Vishnu, not lndra, is the

most important god left from the Vedic pantheon and is thus fitted for a place

in the triad. Similarly Rudra or Shiva is early identified with fire, from his

role as god of red lightning, and can take the place of Agni. The first

conjunction of the Hindu gods was in Harihara, where Vishnu and Shiva were

treated as one deity. But this union ran counter to the tradition of the triad,

and perhaps for form's Brahma, being officially the All-god was added to make

up a triad.

This

triad was not, however, simply derivative from the fire triad it introduced the

new idea of conjunction and unity of creation, preservation and destruction,

which lined with the new concept of a cycle of life, death and rebirth. To a

great ex-tent the triad as such was of mystic significance; but though the idea

of a triune god embracing all three components was an old one, it became

particularly important in the context of sectarian belief, where the followers

of either Vishnu or Shiva sought to assert, and to prove by myths, that their

god was the greatest and actually contained the triad within him.

One

such myth relates that Vishnu and Brahma fell into a dispute as to which of

them was the more venerable. When they had been quarrelling for some time there

appeared before them a fiery pillar, like a hundred universe consuming fires.

Both gods were amazed at the sight and both decided that they must find the

source of the column. So Vishnu took the form of a mighty boar and followed the

column downwards for a thousand years, while Brahma took the form of a

swift-moving swan and travelled upwards along the column for a thousand years.

Neither reached the end and so returned. When they net again, wearily, where

they had started, Shiva appeared before them; they now recognised that the

column was Shiva's lingam, and acknowledged him the greatest and most venerable

of the gods.

Brahma

As

Creator, Brahma is sometimes said to have been the first of the gods, the

framer of the universe and the guardian of the world. At other times, how-ever,

he is said to be himself the creature of the Supreme Being, Pitamaya, the

self-existing father of all human beings. In the Puranas Brahma is held to be

the son of the supreme being and maya, his energy; or he is thought to have

hatched out from the golden cosmic egg, which floated on the cosmic waters; or

to have been born from a lotus which sprang from Vishnu's navel.

Though

he is sometimes thought to be self-created, Brahma's role, when he is

considered as one of the triad of Hindu gods, is exclusively that of creator,

his earlier position as All-god generally passing either to Vishnu or to Shiva.

As the world is already created, much more interest is aroused by these other

gods, the Preserver and Destroyer, who 'captured' the myths originally ascribed

to Brahma, such as his ten forms, which we shall consider as Vishnu's avatars.

Only traces of these myths survive, for example in Manu's creation myth, where

Brahma appears as a fish. Brahma often figures in the main body of Hindu

mythology as the inferior of Vishnu or Shiva, or as the victim of a sage or

demon, who by practicing austerities forces Brahma to make a concession and so

a situation where Vishnu or Shiva must intervene.

Formally

Brahma is revered as the equal of Vishnu and Shiva. He is the god of wisdom,

and the four Vedas are said to have sprung from his heads. His heaven is said

to contain in a superior degree all the splendors of the other heavens of the

gods and of the earth.

Brahma

rides a goose and is depicted with red skin and wearing white robes. He has

four arms and carries the Vedas and his sceptre, or a spoon, or a string of

beads, or a bow, or a water jug. His most salient features, however, are his

four heads. Originally he possessed only one head, but he acquired four more,

and then lost one. Having created a female partner out of his own sub-stance,

Brahma fell in love with her. This modest girl, who is variously called

Satarupa, Savitri, Sarasvati, Vach, Gayatri and Brahmani, was embarrassed by

his fervent look, and moved to avoid his gaze. But as she moved to the right,

to the left and behind him, a new head sprang out in each of these directions.

Finally, she rose into the sky, and a fifth head appeared there to look at her.

Brahma joined with this girl, who was his daughter as well as his wife, to

pro-duce the human race.

It

was Shiva who deprived Brahma of his fifth head, though the story of how this

occurred varies. All versions, however, illustrate the tension existing between

them. Though it is sometimes said that they were born simultaneously of the

supreme being and immediately vied for superiority, some declare Shiva sprang

from Brahma's forehead; others claim that Shiva created Brahma, who worshipped

him and acted as his charioteer. As for Brahma's fifth head, according to one

version Brahma claimed that he was superior to Shiva, who thereupon cut off the

head with his nail. A second version states that Shiva cut off the head because

Brahma told Vishnu a lie in an effort to establish his superiority over Vishnu.

In a third version Shiva punishes Brahma for drunkenly commit-ting incest with

his daughter. A variant of this myth relates that the daughter was Sandhya,

Shiva's wife, who tried to escape her father's advances by changing into a

deer, but was pursued through the sky by Brahma in the shape of a stag. Shiva,

who witnessed all this, shot an arrow which cut off the head of the stag, and

Brahma then paid homage to Shiva. The fourth account says that Brahma wanted

Shiva to be born as a son to him and that Shiva, though he had promised Brahma

that he would grant him any boon, kept his promise but punished him for his

insolence by pronouncing a curse which deprived him of one head. But Shiva thus

committed Brahminicide, for Brahma was considered the chief of the Brahmins. He

was paralysed for his crimes and thus open to attack by a demon created by

Brahma. He fled but was captured and forced to perform penances.

Apart

from being the progenitor of the human race in general, Brahma was the father

of Daksha, who was born from his thumb. Daksha became chief of the Prajapatis,

sages associated with Brahma's creation. Though Daksha gave his daughter to

Shiva as a wife, he insulted the god until, cowed by his violence, he was

forced to acknowledge Shiva's superiority to him and to his father, Brahma.

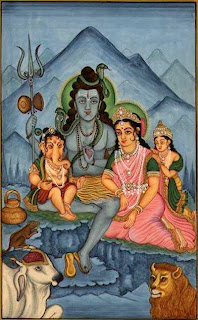

Shiva

Rudra,

Shiva's Vedic forerunner, was the red god of storms and lightning, the

terrifying god living in the mountains and god of cattle and medicine who must

be propitiated. As god of lightning, Rudra became associated with Agni, god of

fire and consumer and conveyor of sacrifice. With Rudra as his antecedent,

Shiva could claim as his inheritance the position of priest of the gods and of

candidate for divine supremacy.

Rudra,

Shiva's Vedic forerunner, was the red god of storms and lightning, the

terrifying god living in the mountains and god of cattle and medicine who must

be propitiated. As god of lightning, Rudra became associated with Agni, god of

fire and consumer and conveyor of sacrifice. With Rudra as his antecedent,

Shiva could claim as his inheritance the position of priest of the gods and of

candidate for divine supremacy.

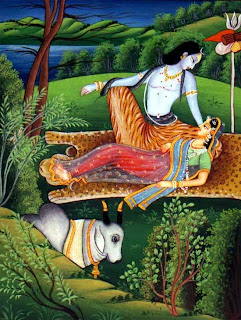

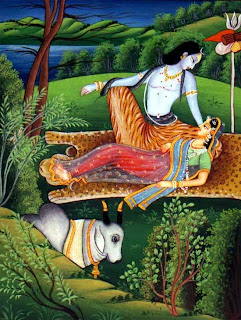

By

contrast with Brahma, a personification of a relatively late abstract

principle, Shiva could combine with his Vedic antecedents features reaching

even farther back than the Vedic age. He had characteristics of the Indus god,

and his powers, especially in the epics, were said to derive from the practice

of austerities, that is from yoga rather than from sacrifice. Such powers

heightened his claims as priest of the gods. In the aspect of a yogi Shiva is

depicted with a snow-white face, is dressed in a tiger skin and has matted

hair.

Rudra's

original character as god of cattle is extended by combining it with that of

the pre-Aryan Lord of the Beasts. The bull is of course universally considered

as a symbol of fertility, and this aspect of the lord of cattle had attached to

Rudra. But the pre-Aryan Lord of the Beasts exacted sacrifice, because of the

ritual connection of sacrifice (death, murder and violence) with plant and

animal fertility a basic cult of agricultural peoples and the foundation of

Indian mythology in pre- and post-Aryan periods. The fertility-giving aspect of

Shiva is thus reinforced by identification with the yogic Lord of the Beasts,

and at the same time the idea of violence present in Rudra is under-lined.

Shiva Bhairava, the Destroyer, is thus by extension Shiva the bringer of

fertility, the creator, the 'Auspicious'. In this sense his activity as

destroyer is essential to that of Brahma as creator, and Brahma is thus

some-times said to be inferior to Shiva. For this reason Shiva is known as

Mahadeva or Iswara, Supreme Lord. His supreme creative power is celebrated in

worship of the lingam or phallus.

Shiva

repeatedly demonstrates his mastery of austerities as the source 0f power. Thus

in the epic version of the slaying of Vritra by lndra, Vritra has obtained

power to create illusions, endless energy, unconquerable might and power over

the gods because Brahma cannot deny it to him after his practice of

austerities. Shiva alone of the gods has sufficient strength gained by yoga to

pit against that obtained by Vritra. It is Shiva who, by backing Indra and

lending him his strength, enables him to overcome Vritra.

On

another occasion Shiva acquired strength to make him superior to all the gods

combined. At one time the asuras had obtained a boon from Brahma which

consisted of the possession of three castles which could only be conquered by a

deity and then only if he could destroy them with a single arrow. From these

bastions the asuras made war on the gods, none of whom was strong enough to

shoot the fatal shaft. Indra, king of the gods, asked Shiva for his advice;

Shiva replied that he would transfer half his strength to the gods and that

they would then be able to overcome their enemies. But the gods could not

support even half of Shiva's strength, so instead they gave half of their own

strength to Shiva, who proceeded to destroy the asuras. However, he did not

return the gods' strength to them but kept it for himself, and ever after was

the greatest of the gods.

He

is often depicted as a demon-slayer, in which role he is called Natesa, and is

seen dancing on the body of an asura. He sometimes wears an elephant skin

belonging to an asura he killed.

He

is often depicted as a demon-slayer, in which role he is called Natesa, and is

seen dancing on the body of an asura. He sometimes wears an elephant skin

belonging to an asura he killed.

His

boons are also positive: he is worshipped as giver of long life and god of

medicine, and his help is inestimable as strengthener of warriors. He is in a

sense indiscriminate in his role, for he is ready to give help to anyone who

would worship him. Thus in the Mahabharata Arjuna is said to have journeyed to

the Himalayas to propitiate the gods before the outbreak of the great war, but

got into a fight with a mountaineer who was Shiva in disguise. When he

discovered who his adversary was he worshipped him and was not only forgiven

but also given a powerful magic weapon. On the other hand Aswathaman, who was

on the opposing side in the Bharata war, and who also fought tenaciously with

Shiva until he realised who he was, threw himself on a sacrificial fire in the

god's honour, this being the only offering he could make; as a reward for this

Shiva entered into his body, so enabling him to slay all about him.

Among

Shiva's beneficent roles is that of distributor of the seven holy rivers. The

Ganges, which winds round Brahma's city on Mount Meru in the Himalayas,

descends from the mountains in great torrents. Shiva, in order to break the

fall, stands beneath the waters, which wind their way through his matted locks

and divide into seven, the holy rivers of India. Shiva performed a vital

service to the gods and thus to the world during the churning of the ocean of

milk, the object of which was to produce amrita, or ambrosia, which was to

strengthen the gods in their struggle against the demons. After some time the

serpent Vasuki, whom the gods were using as a churning rope, vomited forth

poison, and this was about to fall into the ocean of milk, contaminate the

ambrosia and thus destroy the gods. But Shiva stepped forward, caught the

poison in his mouth, and was saved from swallowing it himself only by the

efforts of his wife Parvati, who by strangling him held the poison in his

throat, which turned it blue.

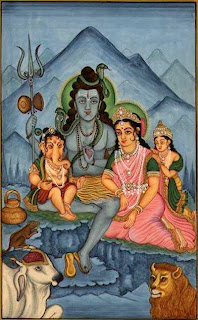

Apart

from his blue throat, Shiva is represented as a fair man, with five faces, four

arms and three eyes. The third eye appeared in the centre of his forehead one

day when Parvati play-fully covered his eyes and thus plunged the world into

darkness and put it in danger of destruction; it is a powerful weapon, for by

fixing it upon his enemies Shiva can destroy them with fire. With this eye, he

kills all the gods and other creatures during the periodic destructions of the

universe. His other weapons are a tri-dent called Pinaka, which is a symbol of

lightning and characterizes Shiva as god of storms; a sword; a bow called

Ajagava; and a club with a skull at the end, called Khatwanga. Further weapons

are the three serpents which twine around him and may dart out at enemies: one

coiled in his piled up, matted hair and raising its hood above his head; one on

his shoulder or about his neck; and one which forms his sacred thread.

In

addition to the weapons, most of Shiva's personal attributes emphasise the

violent aspects of the deity, for which he is most generally known. These

include his head-dress of snakes and necklace of skulls, which he wears when

haunting cemeteries as Bhuteswara, lord of ghosts and goblins. In the character

of Bhairava his violent nature is intensified, for he is then said to take

pleasure in destruction for its own sake. When depicted in such roles Shiva is

attended by troops of imps and demons. In his role as stern upholder of

righteousness and judge, he carries a drum shaped like an hourglass and a rope

with which to bind up sinners.

Apart

from the lingam, personal attributes which characterise Shiva as god of

fertility are the bull Nandi which accompanies him or whose symbol in the shape

of a crescent moon he wears on his brow, encircling his third eye, and the

serpents which twine about him. Many of Shiva's violent aspects are symbolised

in the characters of his consorts, who are particularly associated with his

bloody rites. The yoni, which is their emblem as the lingam is his, is known as

his shakti, or female energy.

Apart

from the lingam, personal attributes which characterise Shiva as god of

fertility are the bull Nandi which accompanies him or whose symbol in the shape

of a crescent moon he wears on his brow, encircling his third eye, and the

serpents which twine about him. Many of Shiva's violent aspects are symbolised

in the characters of his consorts, who are particularly associated with his

bloody rites. The yoni, which is their emblem as the lingam is his, is known as

his shakti, or female energy.

Shiva

likes to dance in joy and in sorrow, either alone or with his wife Devi, for he

is the god of rhythm. Dancing symbolises both the glory of Shiva and the

eternal movement of the universe, which it serves to perpetuate. But by the

Tandava dance he accomplishes the annihilation of the world at the end of an

age and its integration into the world spirit, so that it represents the

destruction of the illusory world of maya. Maya no longer refers to Varuna's

creative energy in the universe; it is that which governs life on earth, the

illusion of material reality, and that from which by various means the faithful

seek to free themselves. When dancing Shiva represents cosmic truth; he is

surrounded by a halo and accompanied by troops of spirits. He is watched by

anyone fortunate enough to be granted the vision. When the serpent Shesha saw

the dance he forsook Vishnu for several years and gave himself up to

austerities in the hope of seeing it again. The gods them-selves assemble to

behold the spectacle, which was treated as proof of Shiva's superiority over

Vishnu by some hermits who till then had lauded only Vishnu. Even demons are

affected by his dance when he performs it in cemeteries, thus bringing the

unclean evil spirits into the orbit of his spiritual power.

But

Shiva is generally depicted immobile, as an ascetic naked, his body smeared

with ashes and his hair matted. His meditation and austerities build up his

spiritual strength, giving him unlimited powers to per-form miracles and also

strengthening his powers as fertility god, for the two roles are not so

antithetical as might at first appear from the myth in which he kills Kama, god

of desire, by burning him up with the fire from his third eye. Though Shiva may

have struck Kama dead for having interrupted his meditations, the effect of

Kama's shaft was not thereby nullified. By still further delaying his union

with Parvati, thereby causing Parvati herself to perform austerities in order

to arouse his interest and causing all the gods to hope anxiously for the

consummation of his desire, Shiva in effect heightened the desire and

strengthened the force of his role as fertility god. The child produced from

his union with Parvati was one of the strongest of the later pantheon:

Karttikeya, god of war, who to some extent supplanted Agni.

It

was the angry sage Bhrigu who caused Shiva to be worshipped in the form of the

lingam. He was sent by the other sages to test the three gods of the triad to

see which was the greatest. When he reached Shiva the god did not welcome him;

he Was engaged with his wife and would not be interrupted. For his lack of

respect due to a sage, Bhrigu cursed Shiva to be worshipped as the lingam.

Brahma also failed to gain Bhrigu's approval, for he was too occupied with his own

self-importance to receive the sage with due courtesy. Vishnu was sleeping when

Bhrigu reached him and the sage rudely kicked him in the ribs Instead of rising

in wrath Vishnu, full of concern, asked him if he had hurt himself, gently

rubbing the foot which had injured him. Bhrigu went away proclaiming that this

was the god most worthy of adoration such compassion and humility before a sage

was the mark of greatness.

Shiva

quarrelled with many of the gods, for though he claimed the right' to judge their

actions and to punish them, many of the other gods in turn considered him to be

a Brahminicide because he struck off one of Brahma’s heads, for which offence

he was condemned to be a wanderer and to perform penances. The gods mocked at him

as an ugly, homeless mendicant unclean, ill-tempered and a haunter of

cemeteries. Eventually, however like Brahma and Vishnu, Shiva acquired a heaven

of his own. This was situated on Mount Kailasa, in the Himalayas, and was the

scene of his austerities and where the Ganges descended on his head.

Though

Shiva quarrelled with many of the gods, his most open disputes were not with

Vishnu, his real rival, but with Brahma. The quarrel was continued in a feud

with Daksha Brahma's son, who became Shiva's father-in-law. When Daksha called

together the assembly at which his daughter Sati was to choose her husband, he

issued invitations to all the gods except Shiva, whom he considered to be

disqualified because of his impure habits and unkempt appearance. But as Sad

had long been a devotee of Shiva and wished to marry no one else, she was disconsolate

to discover Shiva's absence After searching the assembly hall she prayed to him

to appear and threw the garland into the air, where Shiva appeared and received

it. Daksha was thus forced to allow the marriage.

Shiva

had not, however, forgotten the initial insult, and later, when Daksha held an

assembly to which all the gods were invited, he repaid it in kind. As Daksha

entered all the gods rose to greet him, except his father, Brahma, and his

son-in-law, Shiva. Brahma, of course, owed no such deference to his own son:

but the disrespect from his son-in-law enraged Daksha, who declared to the

assembled gods and sages his low opinion of Shiva, a disgrace to the reputation

of the guardians of the world, who encouraged others to transgress and himself

flouted divine ordinances and abolished ancient rites (sacrifice). Daksha

protested against Shiva's ha-bit of haunting cemeteries accompanied by ghosts

and spirits, looking like a madman, with no clothes, smeared with ashes, with

matted hair, and with skulls and human bones about his person; and he denounced

his habit of calling himself 'Auspicious' (Shiva) when in fact he was dear only

to the mad and to the beings of darkness. Having delivered himself of his

tirade, Daksha returned home to plan his next move against Shiva, which was to

hold a great sacrifice without inviting his son-in-law to be present.

Daksha's

revenge was, however, to miscarry. Sati, seeing all the gods trooping off to

the sacrifice, enquired where they were going and was disconsolate when she

heard that they were all going to her father's home. Accordingly she went

herself to see her father and pleaded with him to invite Shiva. But Daksha

merely repeated the strictures he made at the earlier assembly; upon which

Sari, to vindicate her husband's honour, jumped into the sacrificial fire and

was consumed by its flames. Shiva, hearing of this, stormed into Daksha’s house

and, producing from his hair some of the demons with whose company Daksha

reproached him, destroyed the sacrifice. In the uproar which followed he

scattered all the gods and cut off Daksha's head.

Daksha's

revenge was, however, to miscarry. Sati, seeing all the gods trooping off to

the sacrifice, enquired where they were going and was disconsolate when she

heard that they were all going to her father's home. Accordingly she went

herself to see her father and pleaded with him to invite Shiva. But Daksha

merely repeated the strictures he made at the earlier assembly; upon which

Sari, to vindicate her husband's honour, jumped into the sacrificial fire and

was consumed by its flames. Shiva, hearing of this, stormed into Daksha’s house

and, producing from his hair some of the demons with whose company Daksha

reproached him, destroyed the sacrifice. In the uproar which followed he

scattered all the gods and cut off Daksha's head.

He

then gave himself up to insane grief over Sati's death, retrieving her body

from the embers and clasping her to him and calling on her to answer him. So

violent was his emotion and the rhythm of the dance into which he threw

himself, encompassing the world seven times, that the whole universe and its

creatures suffered too. Finally Vishnu, to put an end to this frenzy of

mourning, cut Sati's body, which was still in Shiva's arms, into fifty pieces,

and thus re-stored him to his senses. Shiva repented of his murder of Daksha

and brought him back to life; but the head could not be found, so a goat's head

was used instead.

But

this was not the end of the feud. When Sari was reborn as Parvati and again

married to Shiva, Daksha held another sacrifice and once more failed to invite

Shiva. Parvati spied the festivities from her seat on Mount Kailasa and

informed Shiva who, furious, rushed to the scene. Accounts of what followed

vary.

According

to the famous version, given in the Mahabharata, Shiva pierced the offering

with an arrow and thereby inspired such fear in the gods and sages that the

whole universe quaked. Shiva then attacked the gods, putting out Bhaga's eyes

and kicking Pushan as he was eating the offering and knocking out his teeth; or

alternatively causing Pushan to break his teeth on the arrow embedded in the

offering whereupon the gods acknowledged Shiva as their lord and refuge.

More

interesting are the versions of the myth which introduce Shiva's true rival,

making the issue less the feud with Brahma than a dispute with Vishnu for

supremacy. According to one, Shiva hurled Pinaka, his blazing lightning

trident, which destroyed the sacrifice that Daksha was holding in honour of

Vishnu and then struck Narayana's (Vishnu's) breast. Narayana hurled it back

with equal vigour at Shiva, and a battle flared up between the two gods which

was halted only when Brahma intervened, persuading Shiva to appease Narayana.

There

is even more violence in the version of the myth told in the Puranas when Shiva

heard from Parvati that he had been excluded from the sacrifice. He created a

'being like the fire of fate', called Virabhadra, whose looks and powers were

terrifying, and sent him, together with hundreds of thousands of specially

created demigods, to the place of sacrifice. These creatures broke up the

sacrifice, causing the mountains to totter, earth to shake, winds to roar and

the sea to be disturbed. The gods were routed: Indra was trampled underfoot, Yama's

staff was broken, Sarasvati's nose was cut off, Mitra's eyes were put out,

Pushan had his teeth knocked down his throat, Chandra was beaten, and Agni's

hands were cut off. Then either Daksha admitted Shiva's supremacy, or the

intervention of Vishnu, who seized Shiva by the throat, forced Shiva to desist

and acknowledge Vishnu as his master.

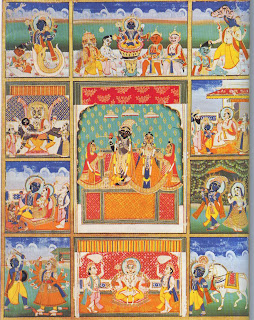

Vishnu

In

the Vedas Vishnu distinguishes himself only for the 'three steps' with which he

measures out the extent of the earth and heavens. The significance of this act

is amplified to include other functions in the epics, where Vishnu is equated

with Prajapati, the creator and supreme god. As Prajapati he encompasses

Brahma, Vishnu himself as preserver, and Shiva as destroyer. As the preserver

he is the embodiment of the quality of mercy and goodness, the self-existent,

all pervading power which preserves and maintains the universe and the cosmic

order, dharma. Vishnu is the cosmic ocean, Nara, which spread everywhere before

the creation of the universe, but is also called Narayana, 'moving in the

waters'; in this character he is represented in a human form, sleeping on the

coiled serpent Shesha, or Ananta, and floating on the waters. Brahma is

sometimes said to have arisen from a lotus growing from his navel as he slept

thus. After each destruction of the universe Vishnu resumes this posture.

According to Vishnu's adherents, he is unlike Brahma and Shiva in that he has

no need to assert his own superiority. Indeed, his mildness combined with his

power proves him to be the greatest of the gods. As the preserver, Vishnu is

the object of devotion rather than of fear, and this affection is similarly

extended to his wife Lakshmi, goddess of fortune.

When

Vishnu is not represented reclining on the coils of the serpent Shesha, with

Lakshmi seated at his feet, he is shown as a handsome young man with blue skin,

dressed in royal robes. He has four hands one holds a conch shell or Sankha, called

Panchajanya, which was once inhabited by a demon killed by Krishna; the second

hand holds a discus or quoit weapon called Sudarsana or Vajranabha, also an

attribute of Krishna's, given to him by Agni as a reward for defeating lndra;

the third hand holds a club or mace called Kaunodaki, presented to Krishna on the

same occasion; the fourth hand holds a lotus, or Padma. He also has a bow

called Sarnga, and a sword called Nandaka. He is usually either seated on a

lotus with Lakshmi beside him, or riding his vehicle, Garuda, who is half-man

and half-bird.

Vishnu's

heaven, Vaikuntha, is on the slopes of the world-mountain Mount Meru. With a

circumference of 80,000 miles, Vaikuntha is made entirely of gold and precious

jewels The Ganges flows through it, and is sometimes said to have its source in

Vishnu's foot. Vaikuntha contains five pools, in which grow blue, red and white

lotuses Vishnu and Lakshmi are ensconced amid the white lotuses, where they

both rdiate like the sun.

Vishnu's

heaven, Vaikuntha, is on the slopes of the world-mountain Mount Meru. With a

circumference of 80,000 miles, Vaikuntha is made entirely of gold and precious

jewels The Ganges flows through it, and is sometimes said to have its source in

Vishnu's foot. Vaikuntha contains five pools, in which grow blue, red and white

lotuses Vishnu and Lakshmi are ensconced amid the white lotuses, where they

both rdiate like the sun.

Though Vishnu existed as a god in Vedic times, his role as

preserver is essentially a late development. It depends upon two

assumptions. First, the theory of samsara, which teaches that every human is

born many times over and that each life represents a punishment or a reward for

his previous life, according to how well he has followed his dharma, or the

path of duty laid down for him in that particular condition of life. If in each

life he has faithfully performed his duty, he may hope to progress steadily

upwards, until he becomes a saint, or even a god. On the other hand, if he does

not perform his duty he progresses as steadily towards life as a demon. The

second assumption is that gods and demons represent the two poles of existence,

and that both are active in the world, a constant struggle being carried on

between the two forces. In the normal course of events, good and evil are

evenly matched in the world; at times, however, the balance is destroyed and

evil gains the upper hand. Such a situation is deemed unfair to humans and at

such times it is Vishnu as preserver who intervenes by descending to earth in a

human incarnation or avatar.

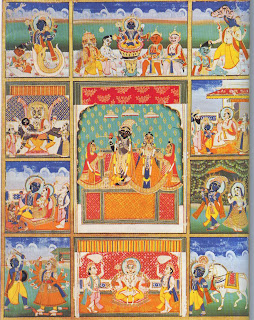

Such

avatars are therefore not chance events, and during each one Vishnu has a

specific task to perform. It is sometimes thought that Vishnu is called upon to

descend to earth in this way once in each cycle of universal time. There are

ten avatars in the present Mahayuga, the first four of which are said to have

occurred during the Kritayuga, and the seventh, eighth and ninth of which are

the best known. Late texts, however, say that there are twenty-two, or even

that they are innumerable.

With

the eighth incarnation, that of Krishna, which became very popular at a

relatively late stage, a new and important idea is added to the older beliefs.

Since Brahmanic times it had been believed that the progressive rise through

countless lives to the level of god to enter Indra's heaven' should not be the

ultimate aspiration; it was far better to practise austerities (yoga) until the

point where the soul became entirely unattached to the individual and was able

to fuse with the universal spirit. The achievement of this release (moksha)

became the ultimate aim, only to be attained by certain gifted spirits, and it

absolved them from the weary round of existences to which they were otherwise

doomed. Now the Krishna myth introduced an important variant to this belief,

for in the course of the Mahabharata the god explains that there is another route

to release of the soul: this is through bhakti, or devotion to a particular god

(in this case Krishna speaks only of devotion to himself, who as Vishnu can in

any case be equated with the universal spirit). Thus by concentrating his

thought on the god a person can hope to merge his or her soul with him and earn

release in a way that is far more attractive than the old discipline of

austerities and yogic concentration. It is this which explains the enormous

popularity of Krishna, who is the most widely worshipped avatar of Vishnu. It

may be remarked in passing that this aspect of his cult has obvious

similarities to Semitic beliefs in a saviour god and that the episodes of

Krishna and the cowgirls resemble Dionysiac cults.

An

interesting twist to the theory of bhakti is seen in the myth relating to

Sisupala, King of Chedi, who hated Krishna so much that he thought of nothing

else but him or Vishnu, even in his sleep and even as he lay dying. And the

consequence of this was that Sisupala too gained release, simply from

concentrating his thoughts so exclusively on the god. Besides the avatars,

Vishnu has a thousand names, the repetition of which is a meritorious act.

Nevertheless,

Vishnu's especial function as preserver remains linked to the older beliefs and

is exercised through his avatars, when he descends to earth as a great hero and

saves mankind and the universe. As a mortal hero, Vishnu guards the righteous,

destroys evil-doers and establishes the reign of law, dharma.

Vishnu's avatars: Matsya

Vishnu's

first incarnation, as a fish,is one borrowed from the mythology of Brahma, and

already described in connection with Manu. In the Vishnu myth, the sage is

called Vaivaswata and is the seventh Manu and progenitor of the human race. The

object of the incarnation was to save Vaivaswata. Vishnu took the form of a small

golden fish with one horn, but grew until he was forty million miles long when

he predicted the deluge. He gave Vaivaswata further help by towing his ship with

a rope attached to his horn and by advising him to allow the ship to descend

slowly with the waters rather than allowing it to become high and dry on the

peak of the Himalayas.

Vishnu's

first incarnation, as a fish,is one borrowed from the mythology of Brahma, and

already described in connection with Manu. In the Vishnu myth, the sage is

called Vaivaswata and is the seventh Manu and progenitor of the human race. The

object of the incarnation was to save Vaivaswata. Vishnu took the form of a small

golden fish with one horn, but grew until he was forty million miles long when

he predicted the deluge. He gave Vaivaswata further help by towing his ship with

a rope attached to his horn and by advising him to allow the ship to descend

slowly with the waters rather than allowing it to become high and dry on the

peak of the Himalayas.

One

version of this story gives a further purpose for the incarnation. During one

of the periods of universal chaos, while Brahma was sleeping the Veda, which

had emerged from his mouth, was stolen by a demon called Hayagriva. As Matsya,

his fish incarnation, Vishnu saved Manu but also instructed him in the true doctrine

of Brahma's eternal soul, and when Brahma woke killed Hayagriva and restored

the Veda.

Kurma

The

second incarnation, as a tortoise Kurma, is also borrowed from the Brahma myth

a relatively simple one where Brahma or Prajapati assumes the form of a

tortoise in order to create offspring. In the Vishnu myth the means of creation

and the objects created are more complex During one of the periodic deluges

which destroyed the world in the first age some things of value were lost, the

most important of which was amrita, the cream of the milk ocean, whose absence

threatened the continued existence of the universe. Accordingly Vishnu

descended to earth as a tortoise to help to recover these objects. Gods and

demons together set about producing amrita by churning the ocean of milk, using

Mount Mandara as a churning stick. Such was the weight of Mount Mandara that

the operation would have been impossible unless Kurma had lent his curved back

as a pivot on which to rest it. With Vishnu (Kurma) supporting the whole, with

the help of the potent herbs which they had thrown into the ocean, and using

the serpent Vasuki as a churning rope, gods and demons proceeded with the task,

and in due course all the precious objects lost in the deluge rose up out of

the milky ocean.

The

ocean gave forth not only the water of life, amrita, but also Dhanwantari,

bearer of the gods' cup of amrita and their physician; Lakshmi or Sri, goddess

of fortune and beauty, Vishnu's wife Sura, goddess of wine; Chandra, the moon,

which Shiva took; Rambha, a nymph, who became the first of the lovely Apsaras;

Uchchaisravas, a beautiful white horse, which was given to the demon Bali, but

afterwards seized by Indra; Kaustubha, a jewel, which went to Vishnu; Parijata,

the celestial wishing tree, which was later planted in Indra's heaven and

belonged to his consort lndrani; Surabhi, the cow of plenty, which was given to

the seven rishis; Airavata, a wonderful white elephant, which became Indra's

mount after he stopped riding a horse; Sankha, a conch shell of victory;

Dhanus, a mighty bow; and Visha, the poison vomited out by the serpent, which

Shiva nearly swallowed.

Varaha

Two

main versions exist of Vishnu's third incarnation, as a boar. The first of

these versions again derives from an earlier Brahma myth, and claims that

Brahma and Vishnu, who were one, took the form of a boar, a water-loving

creature, in order to create the world out of the cosmic waters. The boar,

Varaha, having observed a lotus leaf, thought that the stem must be resting on

something, so he swam down to the depths of the ocean, found the earth below

and brought a piece of it to the surface. The second version of the myth relates

that Brahma had been induced by the propitiation of a demon, Hiranyaksha, to

grant him the boon of invulnerability. Under cover of this boon Hiranyaksha

began to persecute mortals and gods and even stole the Vedas from Brahma and

dragged the earth down to his dark abode under the waters. But Hiranyaksha,

when reciting the names of all the gods, men and animals from whose attacks he

wished to be immune, forgot to mention the boar. Accordingly Vishnu took the

form of a boar forty miles wide and four thousand miles tall, dark in colour

and with a voice like the roar of thunder. He was as big as a mountain, mighty

as a lion, with sharp white tusks and fiery eyes flashing like lightning. With

his whole being radiating like the sun, Vishnu descended into the watery

depths, killed the demon with his tusks, recovered the Vedas and released the

earth, so that it once more floated on the surface.

Narasinha

Vishnu's

fourth incarnation was designed to free the world from the depredations of the

demon king Hiranyakasipu who, like his brother Hiranyaksha, had obtained from

Brahma the boon of immunity from attacks by human, beast and god; he had

Brahma's assurance that he could be killed neither by day nor by night, neither

inside nor outside his house. Protected by this immunity, Hiranyakasipu

overreached himself. He forbade worship of all the gods and substituted worship

of himself. He was therefore particularly incensed to discover that his own son

Prahlada remained an ardent devotee of Vishnu. Hiranyakasipu tried persuasion

and he tried torture, but still Prahlada refused to give up his worship of

Vishnu. Hiranyakasipu finally ordered serpents to bite him to death. But

Prahlada was unaffected, and the serpents fell into feverish disarray, their

fangs broken and fear in their hearts. Vast elephants were sent against

Prahlada; he was thrown over precipices; he was submerged under water. But all

to no avail: Hiranyakasipu could not kill his son. Finally, one evening, the

demon king, in exasperation at his son's repeated assertion of Vishnu's

omnipresence, pointed out a pillar in the doorway of his palace and demanded to

know if Vishnu was there inside it. Prahlada declared that he certainly was,

whereupon Hiranyakasipu said that he would kill him, and he kicked the pillar.

At this Vishnu stepped out of the pillar in the form of Narasinha, a creature

who was half-man and half-lion, and tore Hiranyakasipu to pieces. The

circumstances of Hiranyakasipu's death fell outside the conditions of Brahma's

boon, for the time was evening neither day nor night, the place was the doorway

of the palace not inside nor outside the demon's house, and the assailant was a

man-lion neither human, beast nor god.

The

Varaha and Narasinha avatars are sometimes represented in a composite figure,

Vaikuntha.

Vishnu's

fourth incarnation was designed to free the world from the depredations of the

demon king Hiranyakasipu who, like his brother Hiranyaksha, had obtained from

Brahma the boon of immunity from attacks by human, beast and god; he had

Brahma's assurance that he could be killed neither by day nor by night, neither

inside nor outside his house. Protected by this immunity, Hiranyakasipu

overreached himself. He forbade worship of all the gods and substituted worship

of himself. He was therefore particularly incensed to discover that his own son

Prahlada remained an ardent devotee of Vishnu. Hiranyakasipu tried persuasion

and he tried torture, but still Prahlada refused to give up his worship of

Vishnu. Hiranyakasipu finally ordered serpents to bite him to death. But

Prahlada was unaffected, and the serpents fell into feverish disarray, their

fangs broken and fear in their hearts. Vast elephants were sent against

Prahlada; he was thrown over precipices; he was submerged under water. But all

to no avail: Hiranyakasipu could not kill his son. Finally, one evening, the

demon king, in exasperation at his son's repeated assertion of Vishnu's

omnipresence, pointed out a pillar in the doorway of his palace and demanded to

know if Vishnu was there inside it. Prahlada declared that he certainly was,

whereupon Hiranyakasipu said that he would kill him, and he kicked the pillar.

At this Vishnu stepped out of the pillar in the form of Narasinha, a creature

who was half-man and half-lion, and tore Hiranyakasipu to pieces. The

circumstances of Hiranyakasipu's death fell outside the conditions of Brahma's

boon, for the time was evening neither day nor night, the place was the doorway

of the palace not inside nor outside the demon's house, and the assailant was a

man-lion neither human, beast nor god.

The

Varaha and Narasinha avatars are sometimes represented in a composite figure,

Vaikuntha.

Writer Name: Veronica Lons

Rudra,

Shiva's Vedic forerunner, was the red god of storms and lightning, the

terrifying god living in the mountains and god of cattle and medicine who must

be propitiated. As god of lightning, Rudra became associated with Agni, god of

fire and consumer and conveyor of sacrifice. With Rudra as his antecedent,

Shiva could claim as his inheritance the position of priest of the gods and of

candidate for divine supremacy.

Rudra,

Shiva's Vedic forerunner, was the red god of storms and lightning, the

terrifying god living in the mountains and god of cattle and medicine who must

be propitiated. As god of lightning, Rudra became associated with Agni, god of

fire and consumer and conveyor of sacrifice. With Rudra as his antecedent,

Shiva could claim as his inheritance the position of priest of the gods and of

candidate for divine supremacy.  He

is often depicted as a demon-slayer, in which role he is called Natesa, and is

seen dancing on the body of an asura. He sometimes wears an elephant skin

belonging to an asura he killed.

He

is often depicted as a demon-slayer, in which role he is called Natesa, and is

seen dancing on the body of an asura. He sometimes wears an elephant skin

belonging to an asura he killed.  Apart

from the lingam, personal attributes which characterise Shiva as god of

fertility are the bull Nandi which accompanies him or whose symbol in the shape

of a crescent moon he wears on his brow, encircling his third eye, and the

serpents which twine about him. Many of Shiva's violent aspects are symbolised

in the characters of his consorts, who are particularly associated with his

bloody rites. The yoni, which is their emblem as the lingam is his, is known as

his shakti, or female energy.

Apart

from the lingam, personal attributes which characterise Shiva as god of

fertility are the bull Nandi which accompanies him or whose symbol in the shape

of a crescent moon he wears on his brow, encircling his third eye, and the

serpents which twine about him. Many of Shiva's violent aspects are symbolised

in the characters of his consorts, who are particularly associated with his

bloody rites. The yoni, which is their emblem as the lingam is his, is known as

his shakti, or female energy.  Daksha's

revenge was, however, to miscarry. Sati, seeing all the gods trooping off to

the sacrifice, enquired where they were going and was disconsolate when she

heard that they were all going to her father's home. Accordingly she went

herself to see her father and pleaded with him to invite Shiva. But Daksha

merely repeated the strictures he made at the earlier assembly; upon which

Sari, to vindicate her husband's honour, jumped into the sacrificial fire and

was consumed by its flames. Shiva, hearing of this, stormed into Daksha’s house

and, producing from his hair some of the demons with whose company Daksha

reproached him, destroyed the sacrifice. In the uproar which followed he

scattered all the gods and cut off Daksha's head.

Daksha's

revenge was, however, to miscarry. Sati, seeing all the gods trooping off to

the sacrifice, enquired where they were going and was disconsolate when she

heard that they were all going to her father's home. Accordingly she went

herself to see her father and pleaded with him to invite Shiva. But Daksha

merely repeated the strictures he made at the earlier assembly; upon which

Sari, to vindicate her husband's honour, jumped into the sacrificial fire and

was consumed by its flames. Shiva, hearing of this, stormed into Daksha’s house

and, producing from his hair some of the demons with whose company Daksha

reproached him, destroyed the sacrifice. In the uproar which followed he

scattered all the gods and cut off Daksha's head.  Vishnu's

heaven, Vaikuntha, is on the slopes of the world-mountain Mount Meru. With a

circumference of 80,000 miles, Vaikuntha is made entirely of gold and precious

jewels The Ganges flows through it, and is sometimes said to have its source in

Vishnu's foot. Vaikuntha contains five pools, in which grow blue, red and white

lotuses Vishnu and Lakshmi are ensconced amid the white lotuses, where they

both rdiate like the sun.

Vishnu's

heaven, Vaikuntha, is on the slopes of the world-mountain Mount Meru. With a

circumference of 80,000 miles, Vaikuntha is made entirely of gold and precious

jewels The Ganges flows through it, and is sometimes said to have its source in

Vishnu's foot. Vaikuntha contains five pools, in which grow blue, red and white

lotuses Vishnu and Lakshmi are ensconced amid the white lotuses, where they

both rdiate like the sun. Vishnu's

first incarnation, as a fish,is one borrowed from the mythology of Brahma, and

already described in connection with Manu. In the Vishnu myth, the sage is

called Vaivaswata and is the seventh Manu and progenitor of the human race. The

object of the incarnation was to save Vaivaswata. Vishnu took the form of a small

golden fish with one horn, but grew until he was forty million miles long when

he predicted the deluge. He gave Vaivaswata further help by towing his ship with

a rope attached to his horn and by advising him to allow the ship to descend

slowly with the waters rather than allowing it to become high and dry on the

peak of the Himalayas.

Vishnu's

first incarnation, as a fish,is one borrowed from the mythology of Brahma, and

already described in connection with Manu. In the Vishnu myth, the sage is

called Vaivaswata and is the seventh Manu and progenitor of the human race. The

object of the incarnation was to save Vaivaswata. Vishnu took the form of a small

golden fish with one horn, but grew until he was forty million miles long when

he predicted the deluge. He gave Vaivaswata further help by towing his ship with

a rope attached to his horn and by advising him to allow the ship to descend

slowly with the waters rather than allowing it to become high and dry on the

peak of the Himalayas.  Vishnu's

fourth incarnation was designed to free the world from the depredations of the

demon king Hiranyakasipu who, like his brother Hiranyaksha, had obtained from

Brahma the boon of immunity from attacks by human, beast and god; he had

Brahma's assurance that he could be killed neither by day nor by night, neither

inside nor outside his house. Protected by this immunity, Hiranyakasipu

overreached himself. He forbade worship of all the gods and substituted worship

of himself. He was therefore particularly incensed to discover that his own son

Prahlada remained an ardent devotee of Vishnu. Hiranyakasipu tried persuasion

and he tried torture, but still Prahlada refused to give up his worship of

Vishnu. Hiranyakasipu finally ordered serpents to bite him to death. But

Prahlada was unaffected, and the serpents fell into feverish disarray, their

fangs broken and fear in their hearts. Vast elephants were sent against

Prahlada; he was thrown over precipices; he was submerged under water. But all

to no avail: Hiranyakasipu could not kill his son. Finally, one evening, the

demon king, in exasperation at his son's repeated assertion of Vishnu's

omnipresence, pointed out a pillar in the doorway of his palace and demanded to

know if Vishnu was there inside it. Prahlada declared that he certainly was,

whereupon Hiranyakasipu said that he would kill him, and he kicked the pillar.

At this Vishnu stepped out of the pillar in the form of Narasinha, a creature

who was half-man and half-lion, and tore Hiranyakasipu to pieces. The

circumstances of Hiranyakasipu's death fell outside the conditions of Brahma's

boon, for the time was evening neither day nor night, the place was the doorway

of the palace not inside nor outside the demon's house, and the assailant was a

man-lion neither human, beast nor god.

Vishnu's

fourth incarnation was designed to free the world from the depredations of the

demon king Hiranyakasipu who, like his brother Hiranyaksha, had obtained from

Brahma the boon of immunity from attacks by human, beast and god; he had

Brahma's assurance that he could be killed neither by day nor by night, neither

inside nor outside his house. Protected by this immunity, Hiranyakasipu

overreached himself. He forbade worship of all the gods and substituted worship

of himself. He was therefore particularly incensed to discover that his own son

Prahlada remained an ardent devotee of Vishnu. Hiranyakasipu tried persuasion

and he tried torture, but still Prahlada refused to give up his worship of

Vishnu. Hiranyakasipu finally ordered serpents to bite him to death. But

Prahlada was unaffected, and the serpents fell into feverish disarray, their

fangs broken and fear in their hearts. Vast elephants were sent against

Prahlada; he was thrown over precipices; he was submerged under water. But all

to no avail: Hiranyakasipu could not kill his son. Finally, one evening, the

demon king, in exasperation at his son's repeated assertion of Vishnu's

omnipresence, pointed out a pillar in the doorway of his palace and demanded to

know if Vishnu was there inside it. Prahlada declared that he certainly was,

whereupon Hiranyakasipu said that he would kill him, and he kicked the pillar.

At this Vishnu stepped out of the pillar in the form of Narasinha, a creature

who was half-man and half-lion, and tore Hiranyakasipu to pieces. The

circumstances of Hiranyakasipu's death fell outside the conditions of Brahma's

boon, for the time was evening neither day nor night, the place was the doorway

of the palace not inside nor outside the demon's house, and the assailant was a

man-lion neither human, beast nor god.

0 Response to "Hindu Mythology "

Post a Comment