The

Kubjika Tantra, a late work probably related to the Gorakhnath tradition, says.

'Go to India to establish yourself in the whole country and make manifold

creations in the sacred places of primary and secondary importance.' The

goddess Kubjika is the tutelary deity of the low-caste potters, who are

therefore said to belong to the kubjikamnaya or the Kubjika tradition; the

goddess is also worshipped by the Bhutiyas of Almora and has many small shrines

in the Nepalese and Indian, terai. It being Siva who gives the order to the

goddess in the stanza quoted above, the idea seems to be that she should

proceed from their home, Mount Kailasa in Tibet, and establish her own worship

in India.

The

terms 'Cinacara’ and `Mahacina’ are used as synonyms in the Taratantra which

has been adopted by Hindu and Buddhist tantrics. The age of this text is

unknown, and no one seems to have tried to date it even approximately."

The Tantra says that the cult of Cina-Tara came from the country of Mahacina.

The great Brahmin seer Vasistha went to Mahacina to meet the Buddha and obtain

instruction from him. This episode is only mentioned in the Taratantra; the

text, however, which presents it in detail, is the Rudrayamala, a text whose

age cannot be determined yet; its popularity in Bengal and Assam might indicate

that it is of Bengali origin; it is certainly later than the Mahanirvana, as it

quotes several passages from the latter which is usually ascribed to the

eleventh century A.D. By that time, organized Buddhism, had virtually

disappeared from India, and the Vajrayana tradition had been effectively

disparaged by the Hindu pandits. It is all the more astonishing that this

account of Vasistha, a patron sage of the orthodox Brahmins, is related here in

such detail, though the rest of the work teaches orthodox Brahmanical views.

The account is found in the eighteenth chapter of the Rudrayamala Vasistha the

self-controlled, the son of Brahma, practised austerities for many ages in a

lonely place. He did spiritual exercises (sadhana) for six thousand years, but

still the daughter of the Mountain (i.e. the goddess Parvati, Sakti) did not

appear to him. Getting angry, he went to his father and told him the method of

his sadhana. He then requested Brahma: 'Give me another mantra, O Lord, since

this one does not grant me siddhi (i.e. the desired success, vision of the

goddess), else I shall utter a terrible curse in your presence.' Brahma

dissuaded him and said: 'O son, who art learned in the path of yoga, do not act

like this. Worship her again with full devotion, then she will appear and grant

you boons. She is the supreme Sakti . . . [here follows an enumeration of the

various qualities and epithets of the goddess). . . . She is attached to the

pure Cinacara (Suddha-Cinacara-rata; i.e. the ritualistic method of Gina). She

is the initiator of the Sakti-cakra (Sakti-Cakra-pravartika; i.e. the circle of

worshippers of the goddess). . . . She is Buddhesvari, i.e. the Preceptress

of-Buddha....’ Having heard (these admonitions of Brahma) . . . he (Vasistha)

betook himself to the shores of the sea. For a thousand years he did japa

(repetition) of her mantra; still he received no instructions from her. Thereupon

the sage grew extremely angry, and being perturbed in his mind he began to

curse the Mahavidya (i.e. the goddess). Having sipped water (i.e. having done acamana

the ritualistic sipping of water which precedes any religious and many profane

actions of the Brahmins) he uttered a great, terrible curse. Thereupon the Lady

of the tantrics (Kulesvari) appeared before the sage. She who dispels the

yogis' apprehensions said: 'How now, Brahmin, why lust thou uttered a terrible

curse without any reason? Thou dost not understand my tantric precepts

(kulagama), nor knowest thou how to worship me. How can a god or a man ever

obtain the sight of my lotus-feet by mere yoga practice (yogabhyasamatra)?

Meditation on me is without austerity and without pain. To him who desires my

tantric precepts (kulagama), who is successful (siddha) in my mantra, and who

has known my Vedic precepts (already), my sadhana (exercise for final vision)

is meritorious and inaccessible even to the Vedas (vedanamapyago-cara). Roam in

Mahacina, the country of the Buddhists, and always follow the Atharvaveda

(bauddhadese 'tharvavede mahacine' sada Vraja). Having gone there and seen my

lotus-feet which are mahabhava (i.e. the total bliss experience which is my

essence) thou shalt, O great seer, become versed in inv kula (i.e. the tantric "family")

and a great siddha (adept): Having thus spoken, she became formless and

vanished into the ether and then passed through the ethereal region. The great

seer having heard this from the Mahavidya Sarasvati went to the land of Gina

where Buddha is established (buddhapratisthita). Having (there) repeatedly

bowed to the ground, Vasistha said: 'Protect me, O Mahadeva who art

imperishable in the form of Buddha (buddharupe Mahadeva). I am the very humble

Vasistha, son of Brahma. My mind is ever perturbed. I have come here to Gina

for the Sadhana of the great goddess. I do not know the path leading to siddhi

(occult success). Thou knowest the path of the devas. Yet, seeing the type of

discipline (viz, the left-handed rituals involved), doubts assails my mind.

Destroy them and my wicked mind bent on the Vedic ritual (only). O Lord, in thy

abode there are rites which have been ostracized from the Veda (vedabahiskrtah).

How is it that wine, meat, woman are drunk, eaten, and enjoyed by heaven-clad

(i.e. nude, digambara) siddhas (adepts) who are excellent (varah) and trained

in the drinking of blood? They drink constantly and enjoy beautiful women

(muhurmuhuh prapibanti ramayanti varan-ganam). With red eyes they are always

exhilarated and replete with flesh and wine (sada mamsasavaih purnah). They

have power to give favours and to punish. They are beyond the Vedas

(vedasyago-carah). They enjoy wine and women (madyastrisevane ratah).' Thus

spoke the great yogi, having seen the rites which are banned from the Veda.

Then bowing low with folded palms he humbly said, 'How can inclinations such as

these be purifying to the mind? How can there be siddhi (occult success)

without the Vedic rites?'

The

Buddha then proceeds to explain the Cinacara (the discipline of Gina) at length

to the Brahmin sage, and the explanation boils down to a hierarchy of spiritual

disciplines, the lowest of them being that for `pasus' (lowly type of

aspirants), tantamount to the Vedic ritual, the highest and most efficient

being Cinacara involving the use of wine, meat, women, etc. The text then

concludes thus: 'Having said this, he whose form is Buddha made him (i.e.

Vasistha) practise sadhana (spiritual exercises). He said, "0 Brahmin, do

thou serve Mahasakti. Do thou now practise sadhana with wine and thus shalt

thou get the sight of the lotus-feet of Mahavidya (i.e. the goddess—all the

terms used here are synonyms for the goddess, i.e. Mahasakti, Mahavidya,

"the great power", "the great knowledge" Sarasvati, etc.).'

Vasistha then did as he was told and obtained siddhi through Cinacara.

The

Brahmayamala is a similar text, though it does not seem to be quite so popular

in Bengal as the Rudrayamala. P. C. Bagchi thought it was composed in the

eighth century.33 The Brahmayamala gives a similar account of this key episode,

a difference being that Vasistha starts off at Kamakhya, the famous pitha

(shrine) of the goddess in Assam, not far from the Tibetan and the Chinese

border. Here, Vasistha complains of his failure and is told to go to the Blue

Mountains (Nilacala) and worship the supreme goddess at Kamakhya (Kamrup,

Assam). He was told that Vishnu in the form of the Buddha alone knew the ritual

according to the indispensable Cinacara. Vasistha therefore went to the country

of Mahacina, which is situated on the slope of the Himalaya" and which is

inhabited by great adepts and thousands of beautiful young damsels whose hearts

were gladdened with wine, and whose minds were blissful due to erotic sport

(vilasa). They were adorned with clothes which kindle the mood for dalliance

(srngaravesa) and the movement of their hips made their girdles tinkle with

their little bells. Free of fear and prudishness, they enchanted the world.

They surrounded Isvara in the form of Buddha. . . . When Vasistha saw Him in

the form of Buddha (buddharupi) with eyes drooping from wine, he exclaimed:

'What, is Vishnu doing these things in his Buddha-form? This acara (method) is

certainly opposed to the teaching of the Veda (vedavadaviruddha). I do not

approve of it.' When he thus spoke to himself he heard a voice coming from the

ether saying: 'O thou who art devoted to good acts, do not entertain such

ideas. This tiara (method) yields excellent results in the worship of Tarini

(i.e. Tara). She is not pleased with anything which is contrary to this (acara).

If thou dost wish to gain Her grace speedily, then worship her according to

Cinacara (the method of Cilia). . . Buddha, who had taken wine ... spoke to

him: 'The five makaras (i.e. the ingredients of left-handed tantric ritual,

mada wine, matsya fish, mamsa meat, mudra parched kidney bean and other

aphrodisiacs, and maithuna or ritualistic copulation) are (constituents of)

Cinacara . . . and they must not be disclosed (to the non-initiate).’

The

Buddhist goddess Tara and the goddess Nilasarasvati (i.e. the blue goddess

Sarasvati) are probably identical. She is called 'aksobhya-devimurdhanya'

(having Aksobhya on her head')—and she is said to dwell 'on the west side of

Mount Meru', implying Mahacina, Bhota, etc. The text is the fifth chapter of

the Sammoha Tantra which is a rather late Hindu or Buddhist work current in

Nepal it was composed approximately in the thirteenth century according to

Sastri's introduction. The text is a good specimen of Professor Edgerton's

Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit. Bagchi renders it thus: Mahasvara said to Brahma:

'Hear from me with attention about Mahanilasarasvati. It is through her favour

that you will narrate the four Vedas. There is the lake called Cola on the

western side of Mount Meru. The Mother Goddess Nilogratara herself was born

there. . . . The light issuing from my upper eye fell into the lake Cola and

took on a blue color. There was a sage called Aksobhya, who was Siva himself in

the form of a muni (seer), on the northern side of Mount Meru. It was he who

meditated first on the goddess, who was Parvati herself reincarnated in Cinadesa

(the country Cina) at the time of the great deluge...

Bagchi

adds, 'It is idle to try to find out a precise geographical information here,

but it may be suggested that Cola is probably to be connected with the common

word for lake kul, kol, which is found with names of so many lakes to the west

and north of T'ien shan, i.e. in the pure Mongolian zone.'

The

third chapter of our Sammoha Tantra enumerates a number of pithas (centres of

worship of a female deity), and divides them into regions according to their

use of the kadi and the hadi methods, respectively. `Bhota', `Mahacina', and

`Cina' are enumerated only with kadi pithas. The commonly accepted, though by

no means undisputed, orthodox idea is that kadi mantras and their use as part

of a ritualistic method are aimed at securing worldly or magical success hadi

mantras on the other hand are said to help towards the supreme achievement of

nirvana or its Hindu equivalents. I think that something like this accounts for

the fact that Bhota, Cina, Mahacina are listed in kadi areas, and not in the

hadi area enumeration. The regions beyond the mountain stand for magic and

siddhi whose pursuits are always viewed to an extent as heretical. Some of the

hadi regions listed in the text 'cannot be identified' so Bagchi avers; some of

them, however, seem to be adjacent to Tibetan soil but are still cis-Himalayan

thus `Balhika' which must be Balkh, `Dyorjala' which might well be a

predecessor of 'Darjeeling', which name is derived either from Tibetan

rDorje-glin 'thunderbolt (vajra-) region', or from Sanskrit durjayalinga, 'the

invincible Siva.

The

same text also lists the number of tantras current in different regions, and

claims 'in Gina there are a hundred principal and seven subsidiary ones'. I do

not know if this number correlates with any listing of the Rgyud-sections in

the Tibetan canon or with any other non-Indian enumeration."

The

Kalivilasa Tantra is a late Hindu text, whose age has not been determined; from

its style I would think we might safely place it between the thirteenth and the

seventeenth centuries. It is very popular among non-tantric Brahmins in Bengal,

and it sounds a note hostile to left-handed rites which were equally popular

with the non-Brahmin tantric groups of Bengal. The text condemns the

ritualistic use of women, wine, etc., and says that the tantras enjoining

left-handed ritual are 'prohibited in our era' (Kalau varjitani). The

Kalivilasa, quoting the Mahasiddhasarasvati Tantra, says that the tantras of

the Asvakranta region, i.e. the region from the Vindhya mountains northward

including Nepal, Tibet, etc., were promulgated to confuse the hypocrites

(pasanda) and the heretics. Quoting the Kularnava Tantra, the text says

Mahadeva (Siva) spoke of the kaula-rites (the left-handed rites of the Asvakranta

region) 'lest all men should get liberated (i.e. prematurely)' which is a

rather insidious statement against left-handed forms of tantric practice, in a

tantric text of the right-handed tradition.

The

next quotation is from the famous Karpuradistotram, a Hindu tantric work which

has given much pain to non-tantric Hindus. The work is fairly old; though

Avalon" did not try to establish any date, I would place it between the

ninth and eleventh centuries; its style bears marked similarity to that of the

Saundary-alahari traditionally ascribed to, but certainly not much more recent

than Samkaracarya (eighth century); the latter inspired a lot of poetical piety

among tantrics and non-tantrics in the following two or three centuries, and I

think this work can be safely classed as belonging to this category. It has

been extremely popular in Bengal and Assam up to this day. Of all the major

Hindu Sakta tantras, this one is the most radically left-handed'. Verse I6

says: 'Whosoever on Tuesday midnight . . . makes offering but once with

devotion of a hair of his Sakti in the cremation ground, becomes a great poet,

a Lord of the earth, and goes forth mounted on an elephant.' Now the

commentator explains this passage as `(he who) offers a pubic hair of his Sakti

with its root ritualem post copulationem semine suo unctam." In a sub

commentary called Rahasyarthasadhika (i.e., aid to the hidden meaning [of the

Karpuradistotra]), Vimalananda Svami says that this refers to ‘Mahacina sadhana'

and to the sadhana (mode of worship) of the Goddess Mahanila who is worshipped

in that region. This note which is not called for by the text would corroborate

my previous suggestion a text which

expatiates left-handed rites will usually be given a metaphorical ('afferent'

in my terminology) interpretation by an orthodox Hindu commentator; but if the

text is so overtly left-handed that no such interpretation is possible, the

doctrine is made to lie outside India and Mahacina is a sort of scapegoat. Once

this is done, there are no scruples about putting it thickly, i.e. yoni-sisna-galitabija-yuktam

samulam cikuram, ibid., `radice extirpatem capillam Cum semine membro virile

pudendoque muliebre ablata, sc. qui offert.'

The

Kaulavalinirnaya must be a late text (about sixteenth century), as it quotes

from almost all the well-known Hindu tantras including the Karpuradistotram.

The text identifies Tara with the somewhat uncanny Hindu-Buddhist goddess

Chinnamasta, 'Split-Head', the goddess who holds her own chopped-off heads (two

of them) in her hands, blood gushing forth from her decapitated trunk, which

she catches with her mouths thus sup-ported by her hands. Verse 54 says 'he who

is desirous of wealth should meditate through japa-repetition of the mantra on

the Vidya (i.e. Tara, Chinnamasta) through the ritualistic union with the

supreme woman (parayosit either the consecrated 8akti, or, literally, a woman

married to another man; the latter interpretation being the one given by the

opponents of the tantric tradition), emitting his semen in the 'creeper-mood' (latabhava-compounds

with lata-‘creeper', as first constituent always indicate left-handed rites,

the derived meaning being the (consecrated) woman who embraces the adept like a

creeper, 'he, the best of the adepts; let him ceaselessly do japa of his mantra

for the sake of obtaining dharma, artha, and Wm, thus Tara grants quick success

in the Cina-method.'

This

is a typical instance of what I have come to regard as a pervasive convention:

the methods of 'Gina', Mahacina' and `Bhota' the terms seem to be used

interchangeably in these texts are conducive to all kinds of success except

that of total liberation; in this verse there is the most perfect statement of the

convention: Kama creature comforts artha secular success dharma religious merit

leading to better rebirth, but not 'moksa', the supreme human goal are granted

by the votary of the 'Cina', etc., methods.

Verse

59 repeats the proposition expressly for Chinnamasta: 'in the method of

Mahacina, the goddess Chinnamasta bestows success'.

The

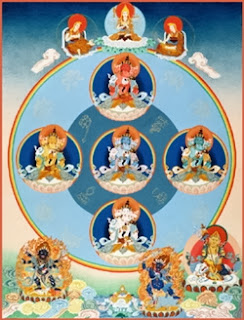

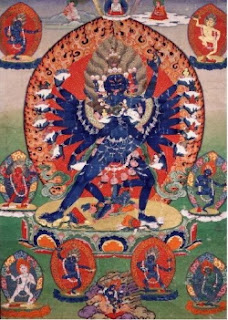

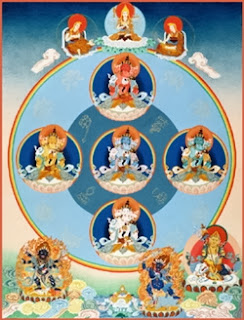

most outstanding purely Buddhist text relevant to our topic is the Sadhanamala,

a Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit classic. The oldest manuscript is of the year A.D.

1167 as the colophon shows." The Sadhanamala has two sadhanas (ritualistic

procedures) dedicated to the goddess Mahacinatara, and two dhyanas

(meditations), one in prose and one in verse, describing the goddess in identical

form. Sadhanamala No. 127 describes her thus: 'she stands in the pratyalidha

posture (i.e. with one leg straight, the other one slightly bent), is

awe-inspiring, has a garland of heads hanging from her neck, is short and has a

protruding belly; of terrible looks, her complexion is like that of the blue

lotus; she is three-eyed, one-faced, celestial, and laughs terribly; in a

pleasantly excited mood (suprahrsta—in the mood of erotic excitement), she

stands on a corpse, is decked with an eightfold snake-ornament, has red, round

eyes, wears garments of tigerskin around her loins, is in youthful bloom, is

endowed with the five auspicious mudras (here postures, i.e. counting her four

hand gestures, and her bodily posture as the fifth), and has a lolling tongue;

she is most terrible, appearing fierce with her bare fangs, carries the sword

and the kartri (in the classical idiom kartari a knife) in her two right hands,

and the lotus and skull in her two left hands; whose crown consisting Of one

chignon is brown and fiery and is adorned with the image of Aksobhya. This is

the Sadhana of Mahacina-Tara; According to the colophon," the Sadhana of

Mahacinatara was restored from a tantra called the Mahacina tantra, and is

attributed to Sasvatavajra.

The

most outstanding purely Buddhist text relevant to our topic is the Sadhanamala,

a Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit classic. The oldest manuscript is of the year A.D.

1167 as the colophon shows." The Sadhanamala has two sadhanas (ritualistic

procedures) dedicated to the goddess Mahacinatara, and two dhyanas

(meditations), one in prose and one in verse, describing the goddess in identical

form. Sadhanamala No. 127 describes her thus: 'she stands in the pratyalidha

posture (i.e. with one leg straight, the other one slightly bent), is

awe-inspiring, has a garland of heads hanging from her neck, is short and has a

protruding belly; of terrible looks, her complexion is like that of the blue

lotus; she is three-eyed, one-faced, celestial, and laughs terribly; in a

pleasantly excited mood (suprahrsta—in the mood of erotic excitement), she

stands on a corpse, is decked with an eightfold snake-ornament, has red, round

eyes, wears garments of tigerskin around her loins, is in youthful bloom, is

endowed with the five auspicious mudras (here postures, i.e. counting her four

hand gestures, and her bodily posture as the fifth), and has a lolling tongue;

she is most terrible, appearing fierce with her bare fangs, carries the sword

and the kartri (in the classical idiom kartari a knife) in her two right hands,

and the lotus and skull in her two left hands; whose crown consisting Of one

chignon is brown and fiery and is adorned with the image of Aksobhya. This is

the Sadhana of Mahacina-Tara; According to the colophon," the Sadhana of

Mahacinatara was restored from a tantra called the Mahacina tantra, and is

attributed to Sasvatavajra.

The

Hindus took over this goddess into their later pantheon; the Tararahasya of

Brahmananda who taught in the sixteenth century, and the Tantrasara of Krsnananda

Agamavagisa, of still more recent origin, contain iconographical descriptions

of Tara that are almost literally identical with that of Mahacinatara just

quoted. By that time, the distinction between the Hindu goddess Tara, wife of

Siva, and her Buddhist namesake had become completely blurred if indeed it was

ever rigidly adhered to. The two Hindu texts do not mention Mahacina, etc., the

originally alleged provenance of the goddess having either been forgotten or

ignored.

Sadhanamala

No. 14.1 describes the worship of the goddess Ekajata (lit: 'having one

chignon'), so do a few more sadhanas in this collection. The colophon of sadhana

141, however, contains the cryptic words `Aryanagarjunapadaih Bhotesuddhrtam

iti', which B. Bhattacharya renders 'restored from Tibet by Arya Nagar juna',

not the author of the Madhyamika-Karika, but the famous Siddha from among the

eighty-four Vajrayana Buddhist sorcerer-saints, to whom many sadhanas are

attributed. The last text I want to adduce here seems to be the most

complete

Hindu statement of tantric topics pertaining to Tibet, etc. ; from among the

extant Hindu tantric works (i.e. disregarding the aforesaid Mahacina tantra,

which is not known to be extant) the Saktisangama-Tantra contains a whole

chapter captioned Mahacina-krama 'the Method of Mahacina'.

Saktas

all over India regard the Saktisangama as an extremely important text, and its

popularity ranks second perhaps only to the Mahanirvana. The text is fairly old

I would place it in the eighth to ninth century on some inner evidence: first,

there is in it much preoccupation with Vajrayana Buddhist terminology, quite a

few mantras occur in the Guhyasamaja and other Vajrayana works. We have `vajrapuspena

juhuyat ('he should sacrifice by means of the vajra-flower') in the 18th

Patala, No. 17, which presupposes the entire notion of libations based on the

adept's identification. with vajra-hood; or `vairocanastakam pujya tatah

padmantakan yajet' in the i5th Patala, No. 38 (having worshipped the eight

forms of Vairocana he should offer sacrifice to the ones with `-padma' at the

end of their names i.e. the goddesses Manipadma, Vajrapadma, etc.); or again Sularaja

mahakrura sarvabhutapriyamkara, siddhim samkalpitam dehi vajrasula namo'stu

te', 68th Patala, No. 18, i.e. 'O king with the trident (i.e. Siva), great

terrible one, bestowing favours on all the Aims (demons, etc.), give the

desired success, Vajra-trident holder, be praised.' This one is particularly interesting,

as it shows a combination of Hindu and Buddhist elements of equal power. Hence

it seems the Vajrayana literature was either contemporary with or still greatly

in vogue at the time this tantra was composed, which would not be the case

later than A.D. 1000; on the other hand, its doctrines are deeply influenced by

the monistic interpretation of Saktism initiated by Samkaracarya and his

disciples (eighth century), hence I think it is quite justifiable to place it

in between A.D. 900 and i000. The 8aktisaingama is a large work and

three-fourths of its total bulk has been published so far.

I am

giving a free rendering of the `Mahacina-krama section in the Saktisamgama,

which is contained in the Second Book, Tarakhanda, Vol. XCI, G.O.S., p. 104 ff:

The Goddess said to Siva: 'I desire to know the method of Mahacina.' Siva then

replied: 'O Tara-, by the method of Mahacina results are quickly obtained; Brahma-Cina,

the celestial Cina, the heroic Gina, Mahacina, and Gina, these are the five

sections or regions the method of these has been described in two manners, as

“sakala” (with divisions), and as "niskala" (undivided). That which

is sakala is Buddhist, that which is niskala is Brahmin in its application.'

Then Siva seems reluctant to continue with the instruction, as this knowledge

is not even obtainable by the devas, yaksas, by saints and great scholars, etc.

The goddess thereupon implores Siva to be merciful and to reveal it

nevertheless, and moved by her entreaties Siva consents and continues. The

initial portions of the Mahacinakrama are pretty much the same as usual

meditative procedure: a bath must be taken, the mind must be purified through

japa', etc., tarpana (offering of water) has to be made, clean raiments have to

be donned then, 'he should constantly worship the goddess, having bathed and

having taken food (as contrasted to non-tantric procedures where fasting is

enjoined previous to formal worship). At midnight he should bring his sacrifice

through mantra (or, accompanied by the proper mantra, "balim mantrena dapayet",

v. 28). Never should he dislike women, especially not those who participate in

the ritual, and having entered the place for "japa", he should

perform a great number of "japa-s". The adept should go to the woman,

touch her, look at her, O Thou with the Gem in the Crest, he should eat

betel-nuts and other edible ingredients (i.e. used for the ritual); and, having

eaten meat, fish, curds, honey, and drunk wine as well as the other prescribed

edible she should proceed with his japa. In this Mahacina-method there is no

rule about the directions (i.e. about which direction the aspirant has to face,

etc.), nor about time, nor about the posture, etc., nor is there any rule for

the choice of time for "japa", nor for invocation and sacrifice. The

rules are made according to his own liking in this sadhana of the great mantra,

with regard to the garments worn, the posture, the general arrangements, the

touching and non-touching of lustral water. And, O Queen of the Gods, he should

anoint his body with oil, should always chew betel (tambulam bhaksayet sada),

and should dress in all sorts of garments (as he pleases). He should undertake

the mantra-bath (i.e. he should meditate on the mantra in lieu of any ritual,

"mantra-snanam caret"), should always take refuge in me. This, O

Goddess, shall be the sage's bath according to the method of Mahacina (Mahacinakrame

devi viprasnanamidam bhavet). He should keep his mind free from apperceptions,

i.e. in the state of "nirvikalpa"(nirvikalpamanascaret), he should

worship using incense, white and ruby-colored lotus leaves, vilva blossoms (or

rather "the pericarp leaves of the vilva" as opposed to the green

leaves of the vilva tree), and bheruka leaves, etc., but he should avoid (the

use of) the (otherwise auspicious) tulsi leaf. He should further avoid the

vilva leaf there is no contradiction here he should use the vilva blossom, but

should not use the leaf of the vilva tree, though I don't see why. It would be

more natural if the text read “arcayet" instead of "varjayet",

e.g. "varjayed-vilvapatranca" vs. 37), and he should diligently avoid

the abstention from drinking ("matt", a fast where no liquid is

taken). He should not harbor any kind of (sectarian) malice, should not take

the name of Hari (Vishnu), and should not touch the tulsi leaf. He should

always drink wine, O goddess, and should always demean himself like the rutting

elephant (or "like Candala women", matangibhir viharavan low-caste

women are said to be particularly lascivious and given to amorous demeanor); he

should, O goddess, do japam with singular attention.'

‘..

. the threefold horizontal lines of fine sandel paste mixed with kesara

(Rottleria Tinctoria) seeds (kucandanam tripundram ca tatah sakesaram Sive, vs.

44) spread on his forehead, O Siva, wearing a garland of skulls around his neck

and the skull-bowl in his hand, he who is given to this tiara (discipline)

becomes a Mahacinite (Mahacinakrami, one following the Mahacina method); always

in a joyful mood, always serving the devotees, he wears . . . (here follows a

lengthy enumeration of other articles, rosaries, etc.); The goddess then

expresses her doubts as to whether such rites are beneficent, and how Brahmins

can practise them, these rites being obviously non-Vedic (vedavihinasca ye dharma

verse 49). In reply to this query of his spouse, Siva winds up saying that Brahmins

or, as I understand it, people who insist on Brahmin ritual are not entitled to

these (Mahacina) rites in this age (kalau tatra nisiddham syadbrahmananam Mahesvari,

verse 5o.) Those who follow the Gina (identical with Mahacina) rites are dear

to him, if they perform their ablutions in the manner indicated earlier, and if

they eat and enjoy the ingredients designed by him for the rite (sarvameva

hrdambhoje mayi sarvam pratisthitam, verse 57). 'Cherishing these attitudes in

his heart, his mind ever directed towards their fulfilment, abandoning any

dualistic attitude, he becomes Lord of all siddhis (spiritual powers); Brahma

and Vasistha, as well as the other great seers, they all worship in the

undivided method (i.e. the Mahacina-krama) at all times. The worshippers of

Tara", O great goddess, they are the true Brahmins; in this age the great

Brahma-knowledge is indeed hard to attain.’ This, incidentally, seems to

suggest that the rites called 'undivided' (niskala) should be called

Brahmanical who could be more Brahmin-like than Brahma the demiurge and

Vasistha and this in spite of the fact that their origin be located in Tibet.

Summarizing

this chapter, we would have to say that mutual references in Indian and Tibetan

texts arc quite disparate. Whereas the Tibetans have looked to India as the

Phags Yul (Aryadesa) 'the Noble Land', not only as the birthplace of the

Buddha, but as the locus of the original teaching, as the actual or stipulated

centre of Tibetan culture, there is no reciprocity of any sort. Historiography

being a virtually non-existent genre in the Indian tradition, tracts of an

historical or quasi-historical character could hardly have gained the prestige

of religious writings. The Tibetan 'Histories' of Buston and Taranatha are

religious histories; just as the Chinese pilgrims in India were solely

concerned with places of pilgrimage and with Buddhist topography, Tibetan monks

and laymen who visited India through the ages did so only as pilgrims to the

shrines of their faith. With the exception of Mount Kailasa in Tibet, there is

no locality on the northern side of the Himalayas which would be of any

interest to the Indian pilgrim. Thus, whereas it may be difficult to, find any

Tibetan text which does not mention India

Summarizing

this chapter, we would have to say that mutual references in Indian and Tibetan

texts arc quite disparate. Whereas the Tibetans have looked to India as the

Phags Yul (Aryadesa) 'the Noble Land', not only as the birthplace of the

Buddha, but as the locus of the original teaching, as the actual or stipulated

centre of Tibetan culture, there is no reciprocity of any sort. Historiography

being a virtually non-existent genre in the Indian tradition, tracts of an

historical or quasi-historical character could hardly have gained the prestige

of religious writings. The Tibetan 'Histories' of Buston and Taranatha are

religious histories; just as the Chinese pilgrims in India were solely

concerned with places of pilgrimage and with Buddhist topography, Tibetan monks

and laymen who visited India through the ages did so only as pilgrims to the

shrines of their faith. With the exception of Mount Kailasa in Tibet, there is

no locality on the northern side of the Himalayas which would be of any

interest to the Indian pilgrim. Thus, whereas it may be difficult to, find any

Tibetan text which does not mention India

one

way or the other, we have to thumb through tomes of Indian religious literature

to find references to Tibet. Even these references, as was shown in this

chapter, are of a non-geographical, quasi-mythical character. Any place or

region located to the north of the Himalayas seems to stand for the highly

esoteric, slightly uncanny, potentially unorthodox, heretical whether it is

Bhota, Mahacina, or Cinadesa, the actual location of those regions is of no

concern to the Indian hagiographer, not even to the tantric.

There

is, however, a strong fusion of Tibetan and Indian elements in tantric

literature, apparently both Buddhist and Hindu. Names and epithets of deities

both male and female have Indian or Tibetan provenience, and in many cases it

is hard to say where a god or a goddess originated. It is almost impossible to

study this situation diachronically because in the final analysis even purely

Tibetan gods and goddesses may have some sort of Indian background. The village

deities of the pre-Aryans in India never died out. There is a strong tendency

to banish gods, teachings, and other religious configurations, which oppose the

general feeling of orthodoxy in India, and to place them beyond the mountains,

possibly where they can cause no mischief. The erotocentric sadhana called Cinacara

probably got its name due to this tendency; types of religious exercise which

could not be accommodated in the framework of Indian sadhana were thus

extrapolated into an inaccessible region.

We

shall see in the next chapter how sanctuary topography assimilates extraneous

elements, and how it cuts across the boundary lines in a tentative or potential

fashion.

Writer Name: Agehananda Bharati

The

most outstanding purely Buddhist text relevant to our topic is the Sadhanamala,

a Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit classic. The oldest manuscript is of the year A.D.

1167 as the colophon shows." The Sadhanamala has two sadhanas (ritualistic

procedures) dedicated to the goddess Mahacinatara, and two dhyanas

(meditations), one in prose and one in verse, describing the goddess in identical

form. Sadhanamala No. 127 describes her thus: 'she stands in the pratyalidha

posture (i.e. with one leg straight, the other one slightly bent), is

awe-inspiring, has a garland of heads hanging from her neck, is short and has a

protruding belly; of terrible looks, her complexion is like that of the blue

lotus; she is three-eyed, one-faced, celestial, and laughs terribly; in a

pleasantly excited mood (suprahrsta—in the mood of erotic excitement), she

stands on a corpse, is decked with an eightfold snake-ornament, has red, round

eyes, wears garments of tigerskin around her loins, is in youthful bloom, is

endowed with the five auspicious mudras (here postures, i.e. counting her four

hand gestures, and her bodily posture as the fifth), and has a lolling tongue;

she is most terrible, appearing fierce with her bare fangs, carries the sword

and the kartri (in the classical idiom kartari a knife) in her two right hands,

and the lotus and skull in her two left hands; whose crown consisting Of one

chignon is brown and fiery and is adorned with the image of Aksobhya. This is

the Sadhana of Mahacina-Tara; According to the colophon," the Sadhana of

Mahacinatara was restored from a tantra called the Mahacina tantra, and is

attributed to Sasvatavajra.

The

most outstanding purely Buddhist text relevant to our topic is the Sadhanamala,

a Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit classic. The oldest manuscript is of the year A.D.

1167 as the colophon shows." The Sadhanamala has two sadhanas (ritualistic

procedures) dedicated to the goddess Mahacinatara, and two dhyanas

(meditations), one in prose and one in verse, describing the goddess in identical

form. Sadhanamala No. 127 describes her thus: 'she stands in the pratyalidha

posture (i.e. with one leg straight, the other one slightly bent), is

awe-inspiring, has a garland of heads hanging from her neck, is short and has a

protruding belly; of terrible looks, her complexion is like that of the blue

lotus; she is three-eyed, one-faced, celestial, and laughs terribly; in a

pleasantly excited mood (suprahrsta—in the mood of erotic excitement), she

stands on a corpse, is decked with an eightfold snake-ornament, has red, round

eyes, wears garments of tigerskin around her loins, is in youthful bloom, is

endowed with the five auspicious mudras (here postures, i.e. counting her four

hand gestures, and her bodily posture as the fifth), and has a lolling tongue;

she is most terrible, appearing fierce with her bare fangs, carries the sword

and the kartri (in the classical idiom kartari a knife) in her two right hands,

and the lotus and skull in her two left hands; whose crown consisting Of one

chignon is brown and fiery and is adorned with the image of Aksobhya. This is

the Sadhana of Mahacina-Tara; According to the colophon," the Sadhana of

Mahacinatara was restored from a tantra called the Mahacina tantra, and is

attributed to Sasvatavajra.  Summarizing

this chapter, we would have to say that mutual references in Indian and Tibetan

texts arc quite disparate. Whereas the Tibetans have looked to India as the

Phags Yul (Aryadesa) 'the Noble Land', not only as the birthplace of the

Buddha, but as the locus of the original teaching, as the actual or stipulated

centre of Tibetan culture, there is no reciprocity of any sort. Historiography

being a virtually non-existent genre in the Indian tradition, tracts of an

historical or quasi-historical character could hardly have gained the prestige

of religious writings. The Tibetan 'Histories' of Buston and Taranatha are

religious histories; just as the Chinese pilgrims in India were solely

concerned with places of pilgrimage and with Buddhist topography, Tibetan monks

and laymen who visited India through the ages did so only as pilgrims to the

shrines of their faith. With the exception of Mount Kailasa in Tibet, there is

no locality on the northern side of the Himalayas which would be of any

interest to the Indian pilgrim. Thus, whereas it may be difficult to, find any

Tibetan text which does not mention India

Summarizing

this chapter, we would have to say that mutual references in Indian and Tibetan

texts arc quite disparate. Whereas the Tibetans have looked to India as the

Phags Yul (Aryadesa) 'the Noble Land', not only as the birthplace of the

Buddha, but as the locus of the original teaching, as the actual or stipulated

centre of Tibetan culture, there is no reciprocity of any sort. Historiography

being a virtually non-existent genre in the Indian tradition, tracts of an

historical or quasi-historical character could hardly have gained the prestige

of religious writings. The Tibetan 'Histories' of Buston and Taranatha are

religious histories; just as the Chinese pilgrims in India were solely

concerned with places of pilgrimage and with Buddhist topography, Tibetan monks

and laymen who visited India through the ages did so only as pilgrims to the

shrines of their faith. With the exception of Mount Kailasa in Tibet, there is

no locality on the northern side of the Himalayas which would be of any

interest to the Indian pilgrim. Thus, whereas it may be difficult to, find any

Tibetan text which does not mention India

0 Response to "Description on India And Tibet in Tantric Literature"

Post a Comment